Master's Degree Programme Mega-Events, Urban Renewal And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ohio Shanghai India's Temples

fall/winter 2019 — $3.95 Ohio Fripp Island Michigan Carnival Mardi Gras New Jersey Panama City Florida India’s Temples Southwestern Ontario Shanghai 1 - CROSSINGS find your story here S ome vacations become part of us. The beauty and Shop for one-of-a-kind Join us in January for the 6th Annual Comfort Food Cruise. experiences come home with us and beckon us back. Ohio’s holiday gifts during the The self-guided Cruise provides a tasty tour of the Hocking Hills Hocking Hills in winter is such a place. Breathtaking scenery, 5th Annual Hocking with more than a dozen locally owned eateries offering up their outdoor adventures, prehistoric caves, frozen waterfalls, Hills Holiday Treasure classic comfort specialties. and cozy cabins, take root and call you back again and Hunt and enter to win again. Bring your sense of adventure and your heart to the one of more than 25 To get your free visitor’s guide and find out more about Hocking Hills and you’ll count the days until you can return. prizes and a Grand the Comfort Food Cruise and Treasure Hunt call or click: Explore the Hocking Hills, Ohio’s Natural Crown Jewels. Prize Getaway for 4. 1-800-Hocking | ExploreHockingHills.com find your story here S ome vacations become part of us. The beauty and Shop for one-of-a-kind Join us in January for the 6th Annual Comfort Food Cruise. experiences come home with us and beckon us back. Ohio’s holiday gifts during the The self-guided Cruise provides a tasty tour of the Hocking Hills Hocking Hills in winter is such a place. -

Shanghai Metro Map 7 3

January 2013 Shanghai Metro Map 7 3 Meilan Lake North Jiangyang Rd. 8 Tieli Rd. Luonan Xincun 1 Shiguang Rd. 6 11 Youyi Rd. Panguang Rd. 10 Nenjiang Rd. Fujin Rd. North Jiading Baoyang Rd. Gangcheng Rd. Liuhang Xinjiangwancheng West Youyi Rd. Xiangyin Rd. North Waigaoqiao West Jiading Shuichan Rd. Free Trade Zone Gucun Park East Yingao Rd. Bao’an Highway Huangxing Park Songbin Rd. Baiyin Rd. Hangjin Rd. Shanghai University Sanmen Rd. Anting East Changji Rd. Gongfu Xincun Zhanghuabang Jiading Middle Yanji Rd. Xincheng Jiangwan Stadium South Waigaoqiao 11 Nanchen Rd. Hulan Rd. Songfa Rd. Free Trade Zone Shanghai Shanghai Huangxing Rd. Automobile City Circuit Malu South Changjiang Rd. Wujiaochang Shangda Rd. Tonghe Xincun Zhouhai Rd. Nanxiang West Yingao Rd. Guoquan Rd. Jiangpu Rd. Changzhong Rd. Gongkang Rd. Taopu Xincun Jiangwan Town Wuzhou Avenue Penpu Xincun Tongji University Anshan Xincun Dachang Town Wuwei Rd. Dabaishu Dongjing Rd. Wenshui Rd. Siping Rd. Qilianshan Rd. Xingzhi Rd. Chifeng Rd. Shanghai Quyang Rd. Jufeng Rd. Liziyuan Dahuasan Rd. Circus World North Xizang Rd. Shanghai West Yanchang Rd. Youdian Xincun Railway Station Hongkou Xincun Rd. Football Wulian Rd. North Zhongxing Rd. Stadium Zhenru Zhongshan Rd. Langao Rd. Dongbaoxing Rd. Boxing Rd. Shanghai Linping Rd. Fengqiao Rd. Zhenping Rd. Zhongtan Rd. Railway Stn. Caoyang Rd. Hailun Rd. 4 Jinqiao Rd. Baoshan Rd. Changshou Rd. North Dalian Rd. Sichuan Rd. Hanzhong Rd. Yunshan Rd. Jinyun Rd. West Jinshajiang Rd. Fengzhuang Zhenbei Rd. Jinshajiang Rd. Longde Rd. Qufu Rd. Yangshupu Rd. Tiantong Rd. Deping Rd. 13 Changping Rd. Xinzha Rd. Pudong Beixinjing Jiangsu Rd. West Nanjing Rd. -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

Art and Culture Committee HIGHLY RECOMMENDED the SHAPE of TIME CENTRE POMPIDOU X WEST BUND MUSEUM

Art and Culture Committee HIGHLY RECOMMENDED THE SHAPE OF TIME CENTRE POMPIDOU X WEST BUND MUSEUM Daily except Mon until May 9 2021 2600 Longteng Dadao, near Longteng Lu 龙腾大道2600号, 近龙腾路 The Shape of Time takes us on a journey through the shapes and forms that defined art in the 20th century. Displayed in a linear and educational form, the exhibition illustrates a chain of influences across painting and sculptures HIGHLY RECOMMENDED OBSERVATIONS CENTRE POMPIDOU X WEST BUND MUSEUM Daily except Mon until May 9 2021 2600 Longteng Dadao, near Longteng Lu 龙腾大道2600号, 近龙腾路 With the second most extensive collection of modern art in the world, Centre Pompidou can undoubtedly present a his- torical perspective for any medium. In a nonlinear maze-like form, this exhibition brings works by artists that pioneered in video art and experimented with digital imagery spanning from the early 70s to the present day. HIGHLY RECOMMENDED HUGO BOSS ASIA ART 2019 ROCKBUND ART MUSEUM Daily except Mon until Jan 5 2020 20 Huqiu Lu, near Beijing Dong Lu 虎丘路20号, 近北京东路 The Rockbund Art Museum and HUGO BOSS are presenting the exhibition of the HUGO BOSS ASIA ART AWARD. The show will open on October 18th presenting the works of the four finalists from Vietnam, The Philippines, Taiwan, and China. Based on this exhibition, a jury comprised of international experts will select a winner that will take home an award of 300,000rmb. The focus of the selection is always on young artists whose works contribute to the redevelopment of the regional art scene. This year, the public can expect an inter- esting mix of paintings, videos and sound Installations, and performances. -

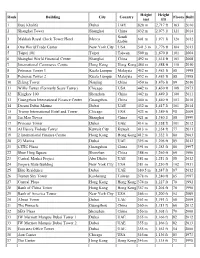

List of World's Tallest Buildings in the World

Height Height Rank Building City Country Floors Built (m) (ft) 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 2 Shanghai Tower Shanghai China 632 m 2,073 ft 121 2014 Saudi 3 Makkah Royal Clock Tower Hotel Mecca 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Arabia 4 One World Trade Center New York City USA 541.3 m 1,776 ft 104 2013 5 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m 1,670 ft 101 2004 6 Shanghai World Financial Center Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 7 International Commerce Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 8 Petronas Tower 1 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 8 Petronas Tower 2 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 10 Zifeng Tower Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 11 Willis Tower (Formerly Sears Tower) Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 12 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 100 2011 13 Guangzhou International Finance Center Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 14 Dream Dubai Marina Dubai UAE 432 m 1,417 ft 101 2014 15 Trump International Hotel and Tower Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 16 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 17 Princess Tower Dubai UAE 414 m 1,358 ft 101 2012 18 Al Hamra Firdous Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,354 ft 77 2011 19 2 International Finance Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 412 m 1,352 ft 88 2003 20 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012 21 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 22 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 23 Central Market Project Abu Dhabi UAE 381 m 1,251 ft 88 2012 24 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 -

22/F One Lujiazui, 68 Yin Cheng Road, Shanghai

22/F One Lujiazui, 68 Yin Cheng Road, Shanghai View this office online at: https://www.newofficeasia.com/details/offices-one-lujiazui-yin-cheng-road-chi na This prominent building towers almost 270 metres over Lujiazui Central Park, in the heart of the Pudong business hub in Shanghai, becoming the centrepiece of an iconic city skyline. These serviced offices can be found on the 22nd storey providing spectacular views of the greenery of the park and beyond to the Bund. The centre is designed to suit the needs of every type of business, large or small. Office spaces range from furnished individual work spaces to larger, more conventional office suites including executive suites, yet all providing a calm and comfortable environment conducive to working efficiently. All in all this is a great opportunity to run your business from a great business environment with flexible service agreements and rental rates. Transport links Nearest tube: Lujiazui station (metro line 2) Nearest railway station: Shanghai Station Nearest road: Lujiazui station (metro line 2) Nearest airport: Lujiazui station (metro line 2) Key features 24 hour access Administrative support AV equipment Car parking spaces Close to railway station Conference rooms Conference rooms High speed internet High-speed internet IT support available Meeting rooms Modern interiors Near to subway / underground station Reception staff Security system Telephone answering service Town centre location Unbranded offices Video conference facilities Location This business centre isl located right in the heart of the financial area of Lujiazui. With all amenities on the doorstep including banks, bars, grocery stores, restuarants etc, plus neighbouring the Lujiazui Central Park, ths area is well served by public transport including Lujiazui station (metro line 2) and bus services. -

Land Reformation and Environmental Upgrading In

World Expo 2010 was held in Shanghai, China. The theme Land reformation and of the exposition is "Better City – Better Life" and signifies Shanghai's new status in the 21st century as a major economic environmental upgrading in the and cultural center. The Expo took place from May 1 to October World Expo in Shanghai (Part 1) 31, 2010 It is expected more than 55% of the world population will be (Land Formation and Development for living in cities by 2015. The theme of the Expo is thus trying to the venue of 2010 World Expo) display urban civilisation to the full extent, exchange their experiences of urban development, disseminate advanced notions on cities and explore new approaches to human habitat, lifestyle and working conditions in the new century. It also Presentation for HKIE Seminar demonstrates how future city can create an eco-friendly society Environmental, CAD & AMC and maintain the sustainable development of human beings 25 March 2017 therein. Within the history of World Expo since 1851, the site for the World Expo 2010 in Shanghai is considered to be Making use of the opportunity accompanied with the unique and made a number of records. For example, it World Expo development, the Municiple government of located in the most congested population zone within a Shanghai planned to restructure and upgrade the entire mega city. The site is situated on the edge of the built-up city to fit the new global standards in terms of urban, area of Shanghai only 3.5 km away from the city centre. cultural, economical and environmental quality and get herself ready to meet any new challenges. -

Looks Can Be Deceiving Guoqiang: Odyssey and Homecom- Says Nouvel

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Friday, July 16, 2021 | 17 LIFE SHANGHAI ince its opening on July 8, safety. Standing in the roof garden, the Museum of Art Pudong people can appreciate the urban has been packed to capacity landscape all around them.” every day. Designed by Touted as a museum for the Srenowned French architecture firm future, MAP is equipped with state- Ateliers Jean Nouvel, MAP has a dai- of-the-art facilities that allow it to ly crowd limit of 4,000. showcase the most precious art- Long lines can be found outside works and cultural relics from the museum every morning before around the world, Chen adds. the official opening at 10 am. Due to One of the most impressive spa- the overwhelming summer heat, the ces within MAP is the X Hall located museum staff have at times even in the center of the museum. Unlike opened the gates earlier to offer traditional exhibition spaces, this some reprieve to the elderly and vis- hall has a height of 34 meters that itors with special need. spans from the underground level Located next to the Oriental Pearl to the fourth story. Tower in the heart of Lujiazui, the The ongoing exhibition at this hall 13,000-square-meter museum has is by well-known Chinese artist Cai become a new landmark in Shang- Guoqiang, who created an installa- hai’s cultural scene. Its inaugural tion to suit this unique space. exhibitions have also been popular Titled Encounter With the among museumgoers. Unknown, the kinetic light instal- In a recent interview with Shang- lation was inspired by the nature- hai-based Wenhui Daily, French based cosmology of the Mayan architect Jean Nouvel said that he civilization and was a result of “a decided the new museum should boy’s fantasy for the space, with “belong” to both the Lujiazui area aliens, UFOs, and gravity-defying and the Huangpu River rather than dreams”, says the 64-year-old art- compete for prominence in the ist from Quanzhou of Fujian urban skyline as there are already province. -

Hou Beiren at 100 百岁北人百岁北人 Contents

Hou Beiren at 100 百岁北人百岁北人 Contents Director’s Preface 5 Celebrating Hou Beiren at 100 7 Mark Dean Johnson My One Hundred Years: An Artistic Journey 13 Hou Beiren Plates 19 Biography 86 3 Director’s Preface Two years ago, at the opening of Sublimity: Recent Works by Hou Beiren, I proposed a toast to Master Hou: “… it was not in the plan prior to this moment, but I hope to present another exhibition of your works two years from now to celebrate your 100th birthday.” Master Hou was a little surprised by my proposal but replied affirmatively right at the moment. Thus we are having this current exhibition – Hou Beiren at 100. In the long course of human history, 100 years is just a blink of the eye. Yet when it comes to a man, 100 years is certainly a magnificent journey, especially considering the vast era of tremendous socio-political changes in modern China that Hou’s life and times encompass. Growing up as a village boy in a small county of Northern China, Hou had lived in China, Japan, and Hong Kong before relocating to the US sixty years ago. Witnessing the ups and downs, whether first-hand in China, or as a sojourner overseas, Hou never gave up his passion for painting. In fact, through painting he had been searching for his “dream”, “ideal” and “soul”, as he wrote in his statement. The mountains and valleys, rivers and creeks, trees and flowers, clouds and mists, waterfalls and rains, are all his heartfelt expressions in the means of ink and colors, and the yearning for a homeland in his dream. -

PPT 0326 Julie Chun

China Art Museum (2012) Power Station of Art (2012) 2011-2019 Natural History Museum (RelocateD 2015) State & Liu Haisu Art Museum (ReloCateD 2016) Shanghai Museum of Glass (2011) Private art Long Museum PuDong (2012) OCAT Art Terminal Shanghai (2012) museums in Shanghai Himalayas Museum (2012) Aurora Museum (2013) Shanghai K11 Art Museum (2013) Chronus Art Center (2013) 21st Century Minsheng Art Museum (2014) Long Museum West BunD (2014) Yuz Museum (2014) Mingyuan Contemporary Art Museum (2015) Shanghai Center of Photography (2015) Modern Art Museum (2016) How Museum Shanghai (2017) Powerlong Art Museum (2017) Fosun FounDation Art Center (2017) Qiao Zhebing Oil Tank Museum (2019) SSSSTART Museum (under Construction) PompiDou Shanghai (unDer ConstruCtion) China Art Museum (2012) Power Station of Art (2012) 2011-2019 Natural History Museum (RelocateD 2015) State & Liu Haisu Art Museum (ReloCateD 2016) Shanghai Museum of Glass (2011) Private art Long Museum PuDong (2012) OCAT Art Terminal Shanghai (2012) museums in Shanghai Himalayas Museum (2012) Aurora Museum (2013) Shanghai K11 Art Museum (2013) Chronus Art Center (2013) 21st Century Minsheng Art Museum (2014) Long Museum West BunD (2014) Yuz Museum (2014) Mingyuan Contemporary Art Museum (2015) Shanghai Center of Photography (2015) Modern Art Museum (2016) How Museum Shanghai (2017) Powerlong Art Museum (2017) Fosun FounDation Art Center (2017) Qiao Zhebing Oil Tank Museum (2019) SSSSTART Museum (under Construction) PompiDou Shanghai (unDer ConstruCtion) Art for the Public Who is the ”public”? Who “speaks” for the public? On what authority? What is the viewers’ reception? And, does any of this matter? Sites for public art in Shanghai (Devoid of entry fee, open access to public) Funded by the city Shanghai Sculpture Space (est. -

China Shanghai 中国上海

Erfahrungsbericht China Shanghai 中国上海 Tongji Universit¨at - Wintersemester 17/18 同济大学 Marius 小马 29. Dezember 2017 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einfuhrung¨ ................................................ 1 1.1 Vorstellung und Vorwort ............................... 1 1.2 Motivation .......................................... 2 2 Vorbereitungen ............................................ 3 2.1 Bewerbung - Deutschland (Hannover) ..................... 3 2.2 Stipendium....................................... 4 2.3 Bewerbung - Tongji (China, Shanghai) . 5 2.4 Unterkunft ........................................ 6 2.5 Visum ............................................. 7 2.6 Kreditkarte....................................... 8 2.7 Handy/Internet ...................................... 9 2.7.1 VPN (Virtual Private Network) . 9 2.7.2 NutzlicheApps¨ ................................... 9 2.8 Auslandskrankenversicherung ......................... 10 2.9 Bedingungen des Prufungsamtes¨ und andere Heimuni spezifische Angelegenheiten ............................. 10 2.10 Flug............................................. 10 3 Erste Schritte vor Ort ..................................... 11 3.1 Registrierung an der Tongji Universit¨at . 11 3.2 Handyvertrag und Internet ............................. 12 3.3 Transport .......................................... 12 3.3.1 Metro........................................... 12 3.3.2 Busse........................................... 13 3.3.3 Taxi............................................. 13 3.3.4 Fahrrad . 13 3.3.5 Scooter ......................................... -

Art Shanghai

WORDS DAVID ELLIOTT PLAYING TO THE GALLERIES While it may have become best known for its explosion of skyscrapers, Shanghai has also been busy building an impressive collection of contemporary art museums. ike Sydney and Melbourne, NYC and LA, and Delhi and Mumbai, Beijing and Shanghai have always competed with each other. As the capital, Beijing has the political Lstatus, but Shanghai has long been the commercial hub of China. In 2008, Beijing proudly presented the Olympic Games, but Shanghai was just as honoured to host the 2010 World Expo. Last year saw the topping out of the Shanghai Tower, China’s tallest (and the second highest in the world), but there are rumours that a new skyscraper in Beijing’s CBD will be even higher. China’s museum and gallery sector is no different. Beijing has claimed superiority, but now Shanghai is a very serious challenger, especially in the new growth area of private museums. Shanghai is huge – by most counts the biggest city in the world – and its art museums are spread out. Luckily, the city’s metro is excellent, so you can get to most of them by under- ground, and short taxi hops will see to the remainder. ❯ The Long Museum, PHOTOGRAPHY: GETTY IMAGES West Bund, Shanghai 82 QANTAS SEPTEMBER 2014 ART SHANGHAI CENTRAL SHANGHAI THE LONG MUSEUM IS ONE A good place to start is Shanghai Museum on People’s Square (201 OF THE BEST TO GAIN AN Renmin Avenue; 9am-5pm daily, free; www.shanghaimuseum.net/ en). Ugly on the outside, fantastic within, it provides a crash course UNDERSTANDING OF 20TH in China’s long cultural history including ceramics, bronze work, CENTURY CHINESE ART sculpture, painting, calligraphy, jade, seals, even furniture.