Feminist Standpoint Theory and the Question of Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Feminist Epistemological Framework: Preventing Knowledge Distortions in Scientific Inquiry

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2019 A Feminist Epistemological Framework: Preventing Knowledge Distortions in Scientific Inquiry Karina Bucciarelli Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses Part of the Epistemology Commons, Feminist Philosophy Commons, and the Philosophy of Science Commons Recommended Citation Bucciarelli, Karina, "A Feminist Epistemological Framework: Preventing Knowledge Distortions in Scientific Inquiry" (2019). Scripps Senior Theses. 1365. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1365 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FEMINIST EPISTEMOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK: PREVENTING KNOWLEDGE DISTORTIONS IN SCIENTIFIC INQUIRY by KARINA MARTINS BUCCIARELLI SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR SUSAN CASTAGNETTO PROFESSOR RIMA BASU APRIL 26, 2019 Bucciarelli 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank my wonderful family for supporting me every step of the way. Mamãe e Papai, obrigada pelo amor e carinho, mil telefonemas, conversas e risadas. Obrigada por não só proporcionar essa educação incrível, mas também me dar um exemplo de como viver. Rafa, thanks for the jokes, the editing help and the spontaneous phone calls. Bela, thank you for the endless time you give to me, for your patience and for your support (even through WhatsApp audios). To my dear friends, thank you for the late study nights, the wild dance parties, the laughs and the endless support. -

Objectivity in the Feminist Philosophy of Science

OBJECTIVITY IN THE FEMINIST PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requisites for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Karen Cordrick Haely, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Louise M. Antony, Adviser Professor Donald C. Hubin _______________________ Professor George Pappas Adviser Philosophy Graduate Program ABSTRACT According to a familiar though naïve conception, science is a rigorously neutral enterprise, free from social and cultural influence, but more sophisticated philosophical views about science have revealed that cultural and personal interests and values are ubiquitous in scientific practice, and thus ought not be ignored when attempting to understand, describe and prescribe proper behavior for the practice of science. Indeed, many theorists have argued that cultural and personal interests and values must be present in science (and knowledge gathering in general) in order to make sense of the world. The concept of objectivity has been utilized in the philosophy of science (as well as in epistemology) as a way to discuss and explore the various types of social and cultural influence that operate in science. The concept has also served as the focus of debates about just how much neutrality we can or should expect in science. This thesis examines feminist ideas regarding how to revise and enrich the concept of objectivity, and how these suggestions help achieve both feminist and scientific goals. Feminists offer us warnings about “idealized” concepts of objectivity, and suggest that power can play a crucial role in determining which research programs get labeled “objective”. -

Baba: the Life Breath of Every Soul” Is Piercing Me from Inside

Om Sri Sai Ram SAI BABA - THE LIFE BREATH OF EVERY SOUL -I By Chandur D. Mirchandani PROLOGUE Volumes of literature have been written by various authors to sing the glory of Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba and to prove His Avatarhood, and to make people understand the purpose of His mission for taking this human form. I am only trying to add a few drops in the infinite ocean of His love and pray to Him right from the bottom of my heart to accept this humble offering as a token of my deep dedication and yearning for the touch of His Lotus Feet, and to bless me with an inner view, so that I am able to understand and put into practice His teachings and His commandments. Baba is an avatar of love. He has graciously taken this human form, for the sake of the seekers of the truth. Year after Year, and from one Yuga to another Yuga, the saints and sages had been earnestly praying to the Almighty God to descend from His heavenly abode and take a human form. In answer to their prayers and for the sake of the yearning of His devotees and to bring Dharma back to its prime position, the God out of His love and compassion has obliged. How fortunate we all human beings are, to be alive and living at the time when the Avatar Himself is moving in a human body while we can keep a personal rapport with Him and receive the benefit of His Darshan (Glimpse), Sparshan (Touch) and Sambashan (Speech). -

Sathya Sai Speaks

SATHYA SAI SPEAKS VOLUME - 34 Discourses of BHAGAWAN SRI SATHYA SAI BABA Delivered during 2001 PRASANTHI NILAYAM SRI SATHYA SAI BOOKS & PUBLICATIONS TRUST Prasanthi Nilayam - 515 134 Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh, India Grams: BOOK TRUST STD: 08555 ISD: 91-8555 Phone: 87375. FAX: 8723 © Sri Sathya Sai Books & Publications Trust Prasanthi Nilayam (India) All Rights Reserved The copyright and the rights of translation in any language are reserved by the Publisher. No part, para, passage, text or photo-graph or art work of this book should be reproduced, transmitted or utilised, in original language or by translation, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or by any information, storage or retrieval system, except with and prior permission, in writing from The Convener Sri Sathya Sai Books & Publications Trust, Prasanthi Nilayam, (Andhra Pradesh) India, except for brief passages quoted in book review. This book can be exported from India only by Sri Sathya Sai Books and Publications Trust, Prasanthi Nilayam (India). International standard book no. International Standard Book No 81 - 7208 - 308 – 4 81 - 7208 - 118 - 9 (set) First Edition: Published by The Convener, Sri Sathya Sai Books & Publications Trust Prasanthi Nilayam, India, Pin code 515 134 Phone: 87375 Fax: 87236 STD: 08555 ISD: 91 - 8555 2 CONTENTS 1. Good Thoughts Herald New Year ..... 1 02. Hospitals Are Meant To Serve The Poor And Needy ..... 13 03. Vision Of The Atma ..... 25 04. Have Steady Faith In The Atma ..... 41 05. Know Thyself ..... 55 6. Ramayana - The Essence Of The Vedas ..... 69 07. Fill All Your Actions With Love .... -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

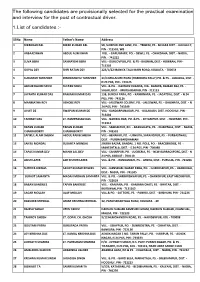

The Following Candidates Are Provisionally Selected for the Practical Examination and Interview for the Post of Contractual Driver

The following candidates are provisionally selected for the practical examination and interview for the post of contractual driver. 1.List of candidates :- Sl No Name Father's Name Address 1 DIPANKAR PAL DIPAK KUMAR PAL 58, SHIBPUR 2ND LANE, PO. - TRIBENI, PS - MOGRA DIST. - HOOGHLY, PIN - 712503, WB 2 ARBAAZ KHAN ABDUL ALIM KHAN VILL. - GARUIMARY, PO. - DEWLI, PS. - CHAKDAHA, DIST. - NADIA, PIN. - 741222 3 SUVA BERA SANNAYSHI BERA VILL - DURLOVPUR, PO. & PS - BAGNAN, DIST.- HOWRAH, PIN - 711303 4 GOPAL DEY SHRI RATAN DEY 223/1/22 MANICK TALA MAIN ROAD, KOLKATA. - 700054 5 SUKUMAR TARAFDER DINOBANDHU TARAFDER 33/3 MULAJORE ROAD (RABINDRA PALLY) PO. & PS. - JAGADAL, DIST. - N 24 PGS, PIN - 743125 6 ABDUR RAHIM SEIKH SULTAN SEIKH VILL. & PO. - DAKSHIN KHANDA, VIA - BANWA, RAIBAD RAJ, PS. - SALAR, DIST. - MURSHIDABAD, PIN - 713123 7 JAYANTA KUMAR DAS RANJAN KUMAR DAS 138, SUNDIA PARA, PO. - KANKINARA, PS. - JAGATDAL, DIST. - N 24 PGS, PIN - 743126 8 MANMATHA ROY ASHOKE ROY VILL - JALESWAR COLONY, PO. - JALESWAR, PS. - GAIGHATA, DIST. - N 24 PGS, PIN - 743249 9 AVIJIT DE SWAPAN KUMAR DE VILL - KANDARPANAGAR, PO. - KULAKASH, DIST. HOOGHLY, PIN - 712404 10 TANMAY DAS LT. RAMPRASAD DAS VILL - NARIKEL BAR, PO. & PS. - SHYAMPUR, DIST. - HOWRAH, PIN - 711314 11 RATAN KUMAR TAPAN KUMAR VILL - SABDALPUR, PO. - ARANGHATA, PS. - DHANTALA, DIST. - NADIA, CHAKRABORTY CHAKRABORTY PIN - 741501 12 SAFIKUL ALAM SHEIKH ABDUL RAKIB SHEIKH VILL - BENAKAR, PO. - UKHURA, SARANGPUR, PS. - PURBASTHALI, DIST. - PURBA BARDHAMAN 13 SANTU MONDAL SUSANTA MONDAL JINJIRA BAZAR, BANDAL. 1 NO. POLE, PO. - BRACEBRIDGE, PS. - MAHESHTALA, DIST. - S 24 PGS, PIN - 700088 14 TAPAS KUMAR DEV MANIK LAL DEV VILL - SAHARPUR, PO. -

Feminist Empiricism Draws in Various Ways

2 FEMINIST EMPIRICISM CATHERINE E. HUNDLEBY eminist empiricism draws in various ways developing new accounts of agency in knowl- on the philosophical tradition of empiri- edge emerges as the second theme in feminist F cism, which can be defined as epistemol- empiricism. ogy that gives primary importance to knowledge Most feminist empiricists employ the meth- based on experience. Feminist demands for atten- odology for developing epistemology known as tion to women’s experiences suggest that empiri- naturalized or naturalist epistemology. Naturalism cism can be a promising resource for developing is controversial, but it welcomes disputation, a feminist account of knowledge. Yet feminists takes up new resources for epistemology on an also value empiricism’s purchase on science and ongoing basis, and encourages multiple approaches the empiricist view that knowers’ abilities depend to the evaluation of knowledge. This pluralism on their experiences and their experiential histo- undercuts naturalism’s and empiricism’s conser- ries, including socialization and psychological vative tendencies and imbues current formula- development. tions of empiricism with radical potential. This chapter explores the attractions of empiricism for feminists. Feminist empiricist analysis ranges from broad considerations about FEMINIST ATTRACTION TO EMPIRICISM popular understandings to technical analysis of narrowly defined scientific fields. Whatever the Empiricism traces in the philosophy of the scope, feminist reworkings of empiricism have global North as far back as Aristotle,1 but it is two central themes. The first theme is the inter- classically associated with the 18th-century play among values in knowledge, especially British philosophers, John Locke, George connecting traditionally recognized empirical Berkeley, and David Hume. -

Developing a Critical Realist Positional Approach to Intersectionality

Developing a Critical Realist Positional Approach to Intersectionality ANGELA MARTINEZ DY University of Nottingham LEE MARTIN University of Nottingham SUSAN MARLOW University of Nottingham This article identifies philosophical tensions and limitations within contemporary intersectionality theory which, it will be argued, have hindered its ability to explain how positioning in multiple social categories can affect life chances and influence the reproduction of inequality. We draw upon critical realism to propose an augmented conceptual framework and novel methodological approach that offers the potential to move beyond these debates, so as to better enable intersectionality to provide causal explanatory accounts of the ‘lived experiences’ of social privilege and disadvantage. KEYWORDS critical realism, critique, feminism, intersectionality, methodology, ontology Introduction Intersectionality has emerged over the past thirty years as an interdisciplinary approach to analyzing the concurrent impacts of social structures, with a focus on theorizing how belonging to multiple exclusionary social categories can influence political access and equality.1 It conceptualizes the interaction of categories of difference such as gender, race and class at many levels, including individual experience, social practices, institutions and ideologies, and frames the outcomes of these interactions in terms of the distribution and allocation of power.2 As a form of social critique originally rooted in black feminism,3 intersectionality is described by Jennifer -

The Foundation of Feminist Research and Its Distinction from Traditional Research Joanne Ardovini-Brooker, Ph.D

Home | Business|Career | Workplace | Community | Money | International Advancing Women In Leadership Feminist Epistemology: The Foundation of Feminist Research and its Distinction from Traditional Research Joanne Ardovini-Brooker, Ph.D. ARDOVINI-BROOKER, SPRING, 2002 ...feminist epistemologies are the golden keys that unlock the door to feminist research. Once the door is unlocked, a better understanding of the distinctive nature of feminist research can occur. There are many questions surrounding feminist research. The most common question is: “What makes feminist research distinctive from traditional research within the Social Sciences?” In trying to answer this question, we need to examine feminist epistemology and the intertwining nature of epistemology, methodology (theory and analysis of how research should proceed), and methods (techniques for gathering data) utilized by feminist researchers. Feminist epistemology in contrast to traditional epistemologies is the foundation on which feminist methodology is built. In turn, the research that develops from this methodology differs greatly from research that develops from traditional methodology and epistemology. Therefore, I argue that one must have a general understanding of feminist epistemology and methodology before one can understand what makes this type of research unique. Such a foundation will assist us in our exploration of the realm of feminist research, while illuminating the differences between feminist and traditional research. An Introduction to Feminist Epistemology Epistemology is the study of knowledge and how it is that people come to know what they know (Johnson, 1995, p. 97). Originating from philosophy, epistemology comes to us from a number of disciplines, i.e.: sociology, psychology, political science, education, and women’s studies (Duran, 1991, p. -

Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements Amanda Huminski The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2826 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPERIMENTAL PHILOSOPHY AND FEMINIST EPISTEMOLOGY: CONFLICTS AND COMPLEMENTS by AMANDA HUMINSKI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 AMANDA HUMINSKI All Rights Reserved ii Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements By Amanda Huminski This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________ ________________________________________________ Date Linda Martín Alcoff Chair of Examining Committee _______________________________ ________________________________________________ Date Nickolas Pappas Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Jesse Prinz Miranda Fricker THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements by Amanda Huminski Advisor: Jesse Prinz The recent turn toward experimental philosophy, particularly in ethics and epistemology, might appear to be supported by feminist epistemology, insofar as experimental philosophy signifies a break from the tradition of primarily white, middle-class men attempting to draw universal claims from within the limits of their own experience and research. -

On the Place of Feminist Epistemology in Philosophy of Education

education sciences Article Knowledge for a Common World? On the Place of Feminist Epistemology in Philosophy of Education Claudia Schumann Department of Education, Stockholm University, Stockholm S-106 91, Sweden; [email protected]; Tel.: +46-816-2000 Academic Editor: Andrew Stables Received: 7 January 2016; Accepted: 3 March 2016; Published: 9 March 2016 Abstract: The paper discusses the place of feminist epistemology in philosophy of education. Against frequently raised criticisms, the paper argues that the issues raised by feminist standpoint theory lead neither to a reduction of questions of knowledge to questions of power or politics nor to the endorsement of relativism. Within the on-going discussion in feminist epistemology, we can find lines of argument which provide the grounds for a far more radical critique of the traditional, narrow notion of objectivity, revealing it as inherently flawed and inconsistent and allowing for the defense of a re-worked, broader, more accurate understanding of objectivity. This is also in the interest of developing a strong basis for a feminist critique of problematically biased and repressive epistemological practices which can further be extended to shed light on the way in which knowledge has become distorted through the repression of other non-dominant epistemic standpoints. Thus, requiring a thorough re-thinking of our conceptions of objectivity and rationality, feminist epistemologies need to be carefully considered in order to improve our understanding of what knowledge for a common world implies in the pluralistic and diverse societies of post-traditional modernity in the 21st century. Keywords: feminist epistemology; situated knowledge; objectivity; relativism 1. -

Keynote Power, Press and Politics Is a Shocking Revelation

Keynote Power, Press and Politics is a shocking revelation about the challenges, threats and manipulations faced by the Indian media professionals from political powerhouses. It’s a ground breaking, insider account from one of the most respected senior journalists of India who has worked with prominent media barons like K.K. Birla , Ashok Jain , Shobhana Bharati & Samir Jain, Senior Editors Manohar Shyam Josahi , Rajendra Mathur , Vinod Mehta and with Editors Guild , also interacted closely with political stalwarts like Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, P.V.Narsimha Rao, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Narendra Modi About The Book How did ‘godman’ Chandraswami get exposed by this journalist, despite this tantric guru being so close to prominent political leaders and media barons? How did this editor go about collecting documentary evidences against Lalu Prasad Yadav in connection with the ‘Fodder Scam’ that eventually got him behind bars and the chilling account of how his supporters attacked the printing unit of Times Group in Patna in vengeance. How editors and investigative correspondents exposed murky arms deals like Bofors , Eurofighter and Naval war room case. How did this editor lay his hands on the controversial personal diary of Govindacharya, senior R.S.S. & BJP leader where Atal Bihari Vajpayee was referred as ‘Mukhota’ ( Mask) of the Party and how he went ahead and published it in a national daily despite Atalji being the Prime Minister of India. How senior editors like him, Vinod Mehta , Kuldip Nayar , B.G. Vergheese , Rajendra Mathur and Manohar Shyam Joshi were forced to resign from media houses due to political and Corporate pressure .