Fish & Wildlife Branch Research Permit Environmental Condition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Storm Data Publication

FEBRUARY 2008 VOLUME 50 SSTORMTORM DDATAATA NUMBER 2 AND UNUSUAL WEATHER PHENOMENA WITH LATE REPORTS AND CORRECTIONS NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION noaa NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SATELLITE, DATA AND INFORMATION SERVICE NATIONAL CLIMATIC DATA CENTER, ASHEVILLE, NC Cover: This cover represents a few weather conditions such as snow, hurricanes, tornadoes, heavy rain and flooding that may occur in any given location any month of the year. (Photos courtesy of NCDC) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Outstanding Storm of the Month …..…………….….........……..…………..…….…..…..... 4 Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....…….…....…………...…...........…............ 5 Reference Notes .............……...........................……….........…..….…............................................ 278 STORM DATA (ISSN 0039-1972) National Climatic Data Center Editor: William Angel Assistant Editors: Stuart Hinson and Rhonda Herndon STORM DATA is prepared, and distributed by the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena narratives and Hurricane/Tropical Storm summaries are prepared by the National Weather Service. Monthly and annual statistics and summaries of tornado and lightning events re- sulting in deaths, injuries, and damage are compiled by the National Climatic Data Center and the National Weather Service’s (NWS) Storm Prediction Center. STORM DATA contains all confi rmed information on storms available to our staff at the time of publication. Late reports and corrections will be printed in each edition. Except for limited editing to correct grammatical errors, the data in Storm Data are published as received. Note: “None Reported” means that no severe weather occurred and “Not Received” means that no reports were received for this region at the time of printing. -

Storm Wind Loads on Trees Thought by the Author to Provide the Best Means for Considering Fundamental Tree Health Care Issues Surrounding Tree Biomechanics

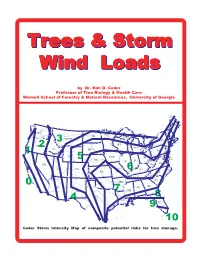

TreesTreesTrees &&& StormStormStorm WindWindWind LoadsLoadsLoads by Dr. Kim D. Coder Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia MAINE WASH. MN. VT. ND. NH. MICH. MONT. MASS. NY. 3 CT. RI. OR. WS. MICH. 2 NJ. ID. 1 SD. PA. WY. IOWA OH. DL. 5 NB. MD. IL. IN. W. NV. VA . VA . UT. CO. 6 KY. KS. MO. NC. CA. TN. SC. ARK. OK. 0 GA. AZ. AL. NM. 7 MS. TX. 8 4 LA. 9 FL. 10 Coder Storm Intensity Map of composite potential risks for tree damage. This publication is an educational product designed for helping tree professionals appreciate and understand basic aspects of tree mechanical loading during storms. This educational product is a synthesis and integration of weather data and educational concepts regarding how storms wind loads impact trees. This product is for awareness building and educational development. At the time it was finished, this publication contained information regarding storm wind loads on trees thought by the author to provide the best means for considering fundamental tree health care issues surrounding tree biomechanics. The University of Georgia, the Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, and the author are not responsible for any errors, omissions, misinterpretations, or misapplications from this educational product. The author assumed professional users would have some basic tree structure and mechanics background. This product was not designed, nor is suited, for homeowner use. Always seek the advice and assistance of professional tree health providers for tree care and structural assessments. This educational product is only for noncommercial, nonprofit use and may not be copied or reproduced by any means, in any format, or in any media including electronic forms, without explicit written permission of the author. -

…Top 10 Weather Events of 2012…

…Top 10 weather events of 2012… In terms of severe weather, 2012 started out fast and furious, and then petered out by late March. 1) By anyone’s measure, the tornado outbreak on the 2nd of March must qualify as our top event of 2012. The 49 mile long EF-4 tornado that tracked across southern Indiana became the first EF-4 in our forecast area since the northern Bullitt County tornado on May 28, 1996. Seven other tornadoes also developed on March 2, with 3 confirmed tornadoes in Trimble County alone. The image to the left shows two supercells following similar paths across southern Indiana. The first cell was producing an EF-4 tornado at this time. The second storm later brought softball sized hail and an EF-1 tornado just south of Henryville. Also, excessively large hail fell across both southern Indiana and south central Kentucky. Outside of several reports of softball-sized hail near Henryville, Indiana, associated with the second of two supercells that tracked over nearly the same path, our most damaging hailstorm developed across southwestern Adair County. This storm produced a hail swath more than 10 miles long, smashing the windshields of hundreds of vehicles before knocking out the skylights of a Walmart store in Columbia. The first picture, courtesy Simon Brewer of The Weather Channel, shows a large tornado in Washington County, IN. The image at left shows hail damage to a golf course near Henryville. 2) The Leap Day tornado outbreak on February 29 featured a squall line that spawned 6 tornadoes across central and south central Kentucky. -

A Winter Forecasting Handbook Winter Storm Information That Is Useful to the Public

A Winter Forecasting Handbook Winter storm information that is useful to the public: 1) The time of onset of dangerous winter weather conditions 2) The time that dangerous winter weather conditions will abate 3) The type of winter weather to be expected: a) Snow b) Sleet c) Freezing rain d) Transitions between these three 7) The intensity of the precipitation 8) The total amount of precipitation that will accumulate 9) The temperatures during the storm (particularly if they are dangerously low) 7) The winds and wind chill temperature (particularly if winds cause blizzard conditions where visibility is reduced). 8) The uncertainty in the forecast. Some problems facing meteorologists: Winter precipitation occurs on the mesoscale The type and intensity of winter precipitation varies over short distances. Forecast products are not well tailored to winter Subtle features, such as variations in the wet bulb temperature, orography, urban heat islands, warm layers aloft, dry layers, small variations in cyclone track, surface temperature, and others all can influence the severity and character of a winter storm event. FORECASTING WINTER WEATHER Important factors: 1. Forcing a) Frontal forcing (at surface and aloft) b) Jetstream forcing c) Location where forcing will occur 2. Quantitative precipitation forecasts from models 3. Thermal structure where forcing and precipitation are expected 4. Moisture distribution in region where forcing and precipitation are expected. 5. Consideration of microphysical processes Forecasting winter precipitation in 0-48 hour time range: You must have a good understanding of the current state of the Atmosphere BEFORE you try to forecast a future state! 1. Examine current data to identify positions of cyclones and anticyclones and the location and types of fronts. -

Using Analogues to Simulate Intensity, Trajectory, and Dynamical Changes in Alberta Clippers with Global Climate Change

Using Analogues to Simulate Intensity, Trajectory, and Dynamical Changes in Alberta Clippers with Global Climate Change Item Type Thesis Authors Ward, Jamie L. Download date 07/10/2021 05:51:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/5573 Using Analogues to Simulate Intensity, Trajectory, and Dynamical Changes in Alberta Clippers with Global Climate Change _______________________ A thesis Presented to The College of Graduate and Professional Studies Department of Earth and Environmental Systems Indiana State University Terre Haute, Indiana ______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _______________________ by Jamie L. Ward August 2014 Jamie L. Ward, 2014 Keywords: Alberta Clippers, Storm Tracks, Lee Cyclogenesis, Global Climate Change, Atmospheric Analogues ii COMMITTEE MEMBERS Committee Chair: Gregory D. Bierly (Ph.D.) Professor of Geography Indiana State University Committee Member: Stephen Aldrich (Ph.D.) Assistant Professor of Geography Indiana State University Committee Member: Jennifer C. Latimer Associate Professor of Geology Indiana State University iii ABSTRACT Alberta Clippers are extratropical cyclones that form in the lee of the Canadian Rocky Mountains and traverse through the Great Plains and Midwest regions of the United States. With the imminent threat of global climate change and its effects on regional teleconnection patterns like El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), properties of Alberta Clipper could be altered as a result of changing atmospheric circulation patterns. Since the Great Plains and Midwest regions both support a large portion of the national population and agricultural activity, the effects of global climate change on Alberta Clippers could affect these areas in a variety of ways. -

What Are We Doing with (Or To) the F-Scale?

5.6 What Are We Doing with (or to) the F-Scale? Daniel McCarthy, Joseph Schaefer and Roger Edwards NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center Norman, OK 1. Introduction Dr. T. Theodore Fujita developed the F- Scale, or Fujita Scale, in 1971 to provide a way to compare mesoscale windstorms by estimating the wind speed in hurricanes or tornadoes through an evaluation of the observed damage (Fujita 1971). Fujita grouped wind damage into six categories of increasing devastation (F0 through F5). Then for each damage class, he estimated the wind speed range capable of causing the damage. When deriving the scale, Fujita cunningly bridged the speeds between the Beaufort Scale (Huler 2005) used to estimate wind speeds through hurricane intensity and the Mach scale for near sonic speed winds. Fujita developed the following equation to estimate the wind speed associated with the damage produced by a tornado: Figure 1: Fujita's plot of how the F-Scale V = 14.1(F+2)3/2 connects with the Beaufort Scale and Mach number. From Fujita’s SMRP No. 91, 1971. where V is the speed in miles per hour, and F is the F-category of the damage. This Amazingly, the University of Oklahoma equation led to the graph devised by Fujita Doppler-On-Wheels measured up to 318 in Figure 1. mph flow some tens of meters above the ground in this tornado (Burgess et. al, 2002). Fujita and his staff used this scale to map out and analyze 148 tornadoes in the Super 2. Early Applications Tornado Outbreak of 3-4 April 1974. -

A Synoptic-Climatology and Composite Analysis of the Alberta Clipper

!"#$%&'()*+*,)-!(&,&.$"!%/"*&-'&#)(0"!%!,$#)#"&1 (20"!,304(!"*,)''04 !" #$%&'()*+),-./%01)234)5.'%,-%')(+)/%6,&'7 1!"#"$%$&$'()*%+,-./)0.1#")2+,34)!1441&")5+,'"/)6"7)!"81-$ 9:";+%#<",#)$=)>#<$4;."%1-)+,3)?-"+,1-)2-1",-"4 @,1A"%41#()$=)014-$,41,B!+314$, C99D)0E):+(#$,)2#E !+314$,/)0F)DGHIJ KJILM)9J9BNLOD P"<+%#1CQ714-E"3R 08!9:;;<4)=>?)@8!A:B2;:>3);>)0"+#."%)+,3)S$%"-+4#1,'C)7D)58A")7EEF "#$%&"'% $()*+,-.+/0.(11-)2+3).+/+456-6.*)78.9:-.;'<=>.%?@".0+9+6-9.+)-.(6-0.97.,7/69)(,9 +.,438+9747A5.7*.BCC."4D-)9+.'4311-)6.7E-).BF.D7)-+4.,740.6-+67/6.G?,97D-)2<+),:H.*)78 BIJK2JC.97.!LLL2LBM..%:-."4D-)9+.'4311-).G:-)-+*9-).638145.!"#$$%&H.7,,()6.8769.*)-N(-/945 0()3/A.O-,-8D-).+/0.P+/(+)5.+/0.6(D69+/93+445.4-66.*)-N(-/945.0()3/A.?,97D-).+/0.<+),:M %:-6-.,5,47/-6.A-/-)+445.87E-.67(9:-+69Q+)0.*)78.9:-.4--.7*.9:-.'+/+03+/.&7,R3-6.97Q+)0 7).S(69./7)9:.7*.T+R-.$(1-)37).D-*7)-.1)7A)-663/A.-+69Q+)0.3/97.67(9:-+69-)/.'+/+0+.7).9:- /7)9:-+69-)/.U/39-0.$9+9-6V.Q39:.4-66.9:+/.BLW.7*.,+6-6.3/.9:-.,438+9747A5.9)+,R3/A.67(9:.7* 9:-.@)-+9.T+R-6M ':+)+,9-)3693,6.7*.9:-.69)(,9()-.+/0.-E74(937/.7*.'4311-)6.0()3/A.+.XK2:.1-)370.4-+03/A (1.97.0-1+)9()-.7*.9:-.,5,47/-.*)78.9:-.4--.7*.9:-.'+/+03+/.&7,R3-6.+/0.+.KL2:.1-)370.+*9-) 0-1+)9()-.+6.9:-.,5,47/-.9)+E-)6-6.,-/9)+4.+/0.-+69-)/.Y7)9:."8-)3,+.+)-.-Z+83/-0.9:)7(A: ,7817639-.+/+456-6M..?E-).9:-.,7()6-.7*.9:-.1)-20-1+)9()-.1-)370V.+.,5,47/-.7E-).9:-.@(4*.7* "4+6R+.+11)7+,:-6.9:-.Q-69.,7+69.7*.Y7)9:."8-)3,+V.+/0.9:)7(A:.396.3/9-)+,937/.Q39:.9:- 87(/9+3/7(6.9-))+3/.7*.Q-69-)/.Y7)9:."8-)3,+.61+Q/6.+.6()*+,-.4--.9)7(A:V.,:+)+,9-)3[-0.D5 -

Synoptic Climatology of Lake-Effect Snow Events Off the Western Great Lakes

climate Article Synoptic Climatology of Lake-Effect Snow Events off the Western Great Lakes Jake Wiley * and Andrew Mercer Department of Geosciences, Mississippi State University, 75 B. S. Hood Road, Starkville, MS 39762, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: As the mesoscale dynamics of lake-effect snow (LES) are becoming better understood, recent and ongoing research is beginning to focus on the large-scale environments conducive to LES. Synoptic-scale composites are constructed for Lake Michigan and Lake Superior LES events by employing an LES case repository for these regions within the U.S. North American Regional Reanalysis (NARR) data for each LES event were used to construct synoptic maps of dominant LES patterns for each lake. These maps were formulated using a previously implemented composite technique that blends principal component analysis with a k-means cluster analysis. A sample case from each resulting cluster was also selected and simulated using the Advanced Weather Research and Forecast model to obtain an example mesoscale depiction of the LES environment. The study revealed four synoptic setups for Lake Michigan and three for Lake Superior whose primary differences were discrepancies in a surface pressure dipole structure previously linked with Great Lakes LES. These subtle synoptic-scale differences suggested that while overall LES impacts were driven more by the mesoscale conditions for these lakes, synoptic-scale conditions still provided important insight into the character of LES forcing mechanisms, primarily the steering flow and air–lake thermodynamics. Keywords: lake-effect; climatology; numerical weather prediction; synoptic; mesoscale; winter weather; Great Lakes; snow Citation: Wiley, J.; Mercer, A. -

January 21, 2014 Winter Storm by Heather Sheffield, General

January 21, 2014 Winter Storm By Heather Sheffield, General Forecaster The snow forecast quickly escalated 36 hours prior to the first snowflakes on Tuesday, January 21, 2014. Model Guidance over the weekend and prior to the event became snowier with each model run and consistency led to the issuance of a Winter Storm Warning on Monday, January 20, 2014. An upper trough was located across the eastern half of the United States. The storm track leading up to this event featured numerous waves of low pressure, called Alberta clippers, diving southeastward around the upper trough from central Canada into the mid-Atlantic region. Alberta clippers typically produce little precipitation since they originate from central Canada- a region without a large source of moisture. However, the one Alberta clipper that moved into the Northern Plains on the Monday afternoon of January 20 was able to tap into deeper moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean as low pressure rapidly developed in the Mid- Atlantic States on Tuesday. The strengthening of low pressure occurred in response to the position of several jet streaks in the upper levels of the troposphere- one over the northern Gulf Coast and another over New England (image below). An arctic cold front dropped southward into the region Tuesday morning, allowing cold air to sink southward into the region and precipitation with this event to be snow. Snow began to move over the Potomac Highlands early Tuesday morning. Reagan National Airport and Southern Maryland were in the upper 30s around sunrise Tuesday morning. Temperatures just before the snow arrived were above freezing across the greater Baltimore and DC metropolitan area due to light easterly surface flow and abundant cloud cover on Monday night, but quickly dropped once snow started to fall (note: temperatures at the NWS forecast office in Sterling, VA drop 5 degrees in 15 minutes at the onset). -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Windstorms Intense Windstorms in the Northeastern United States F

Windstorms Intense windstorms in the Northeastern United States F. Letson1, R. J. Barthelmie2, K.I. Hodges3 and S. C. Pryor1 1Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA 5 2Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA 3Environmental System Science Centre, University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom Correspondence to: F. Letson ([email protected]), S.C. Pryor ([email protected]) Abstract. Windstorms are a major natural hazard in many countries. Windstorms Intense windstorms during the last four decades in the U.S. Northeast are identified and characterized using the spatial extent of locally extreme wind 10 speeds at 100 m height from the ERA5 reanalysis database. During all of the top 10 windstorms, wind speeds in excess of their local 99.9th percentile extend over at least one-third of land-based ERA5 grid cells in this high population density region of the U.S. Maximum sustained wind speeds at 100 m during these windstorms range from 26 to over 43 ms-1, with wind speed return periods exceeding 6.5 to 106 years (considering the top 5% of grid cells during each storm). The propertyProperty damage associated with these storms, (inflation adjusted to January 2020,) is ranges 15 from $24 million to over $29 billion. Two of these windstorms are linked to decaying tropical cyclones, three are Alberta Clippers and the remaining storms are Colorado Lows. Two of the ten re-intensified off the east coast leading to development of Nor’easters. These windstorms followed frequently observed cyclone tracks, but exhibit maximum intensities as measured using 700 hPa relative vorticity and mean sea level pressure that are five to ten times mean values for cyclones that followed similar tracks over this 40-year period. -

NCAR Annual Scientific Report Fiscal Year 1985 - Link Page Next PART0002

National Center for Atmospheric Research Annual Scientific Report Fiscal Year 1985 Submitted to National Science Foundation by University Corporation for Atmospheric Research March 1986 iii CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............... ............................................. v ATMOSPHERIC ANALYSIS AND PREDICTION DIVISION ............... 1 Significant Accomplishments........................ 1 AAP Division Office................................................ 4 Mesoscale Research Section . ........................................ 8 Climate Section........................................ 15 Large-Scale Dynamics Section....................................... 22 Oceanography Section. .......................... 28 ATMOSPHERIC CHEMISTRY DIVISION................................. .. 37 Significant Accompl i shments........................................ 38 Precipitation Chemistry, Reactive Gases, and Aerosols Section. ..................................39 Atmospheric Gas Measurements Section............................... 46 Global Observations, Modeling, and Optical Techniques Section.............................. 52 Support Section.................................................... 57 Di rector' s Office. * . ...... .......... .. .. ** 58 HIGH ALTITUDE OBSERVATORYY .. .................. ............... 63 Significant Accomplishments .......... .............................. 63 Coronal/Interplanetary Physics Section ....................... 64 Solar Variability and Terrestrial Interactions Section........................................... 72 Solar