Holy Trinity and Villainous Multiplicity in the Christian Shape of Macbeth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare Macbeth

Synopsis Macbeth, set primarily in Scotland, mixes witchcraft, prophecy, and murder. Three “Weïrd Sisters” appear to Macbeth and his comrade Banquo after a battle and prophesy that Macbeth will be king and that the descendants of Banquo will also reign. When Macbeth arrives at his castle, he and Lady Macbeth plot to assassinate King Duncan, soon to be their guest, so that Macbeth can become king. After Macbeth murders Duncan, the king’s two sons flee, and Macbeth is crowned. Fearing that Banquo’s descendants will, according to the Weïrd Sisters’ predictions, take over the kingdom, Macbeth has Banquo killed. At a royal banquet that evening, Macbeth sees Banquo’s ghost appear covered in blood. Macbeth determines to consult the Weïrd Sisters again. They comfort him with ambiguous promises. Another nobleman, Macduff, rides to England to join Duncan’s older son, Malcolm. Macbeth has Macduff’s wife and children murdered. Malcolm and Macduff lead an army against Macbeth, as Lady Macbeth goes mad and commits suicide. Macbeth confronts Malcolm’s army, trusting in the Weïrd Sisters’ comforting promises. He learns that the promises are tricks, but continues to fight. Macduff kills Macbeth and Malcolm becomes Scotland’s king. Characters in the Play Three Witches, the Weïrd Sisters Scottish Nobles DUNCAN, king of Scotland LENNOX MALCOLM, his elder son ROSS DONALBAIN, Duncan’s younger son ANGUS MACBETH, thane of Glamis MENTEITH LADY MACBETH CAITHNESS SEYTON, attendant to Macbeth Three Murderers in Macbeth’s service SIWARD, commander of the English -

Macbeth on Three Levels Wrap Around a Deep Thrust Stage—With Only Nine Rows Dramatis Personae 14 Separating the Farthest Seat from the Stage

Weird Sister, rendering by Mieka Van Der Ploeg, 2019 Table of Contents Barbara Gaines Preface 1 Artistic Director Art That Lives 2 Carl and Marilynn Thoma Bard’s Bio 3 Endowed Chair The First Folio 3 Shakespeare’s England 5 Criss Henderson The English Renaissance Theater 6 Executive Director Courtyard-Style Theater 7 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Timeline 12 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style Courtyard Theater, 500 seats Shakespeare's Macbeth on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows Dramatis Personae 14 separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also The Story 15 features a flexible 180-seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Act by Act Synopsis 15 Center, and a Shakespeare specialty bookstall. In 2017, a new, innovative S omething Borrowed, Something New: performance venue, The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare, expanded CST's Shakespeare’s Sources 18 campus to include three theaters. The year-round, flexible venue can 1606 and All That 19 be configured in a variety of shapes and sizes with audience capacities Shakespeare, Tragedy, and Us 21 ranging from 150 to 850, defining the audience-artist relationship to best serve each production. Now in its thirty-second season, the Theater has Scholars' Perspectives produced nearly the entire Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends -

1 Name___KEY___Date___Macbeth: Act

Name_____KEY_____ Date_____________ Macbeth: Act V Reading and Study Guide I. Vocabulary: Be able to define the following words and understand them when they appear in the play. Also, be prepared to be quizzed on these words. perturb: disturb, bother taper: candle note: our word taper that means to make gradually smaller (e.g., to taper someone off a medicine) probably comes from the sense of a taper (candle) gradually diminishing in size as it burns. guise: outward appearance note: think of the word disguise fortify: to strengthen pester: to annoy hew: to cut down abhor: hate, detest; to reject something very strongly Etymology: ab (away) + horror (to tremble; shudder) The word literally means to shrink back (away) in horror (trembling). Word is stronger than hate. II. Background Info: Moirai (3 Fates): In Greek Mythology, these are the three sisters who have the power to decide man’s destiny. The first of the sisters (Clotho) spun the thread of a person’s life and decided what the life would be like. The second (Lachesis) measured the thread of life. She decided how long it would be. The third (Atropos) is the one who cut the thread of life. Essentially, these three sisters determined the length of each person’s life as well as how much suffering. Their names in Roman Mythology are Nona, Decuma, and Morta. And Norse Mythology also has three goddesses of destiny. The exact details of these three goddesses differ in different stories and pieces of art. Most of our information comes from Hesiod’s Theogeny, although there are references in Homer’s Iliad and Plato’s Republic. -

Macbeth in World Cinema: Selected Film and Tv Adaptations

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN 2249-6912 Vol. 3, Issue 1, Mar 2013, 179-188 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. MACBETH IN WORLD CINEMA: SELECTED FILM AND TV ADAPTATIONS RITU MOHAN 1 & MAHESH KUMAR ARORA 2 1Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India 2Associate Professor, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India ABSTRACT In the rich history of Shakespearean translation/transcreation/appropriation in world, Macbeth occupies an important place. Macbeth has found a long and productive life on Celluloid. The themes of this Bard’s play work in almost any genre, in any decade of any generation, and will continue to find their home on stage, in film, literature, and beyond. Macbeth can well be said to be one of Shakespeare’s most performed play and has enchanted theatre personalities and film makers. Much like other Shakespearean works, it holds within itself the most valuable quality of timelessness and volatility because of which the play can be reproduced in any regional background and also in any period of time. More than the localization of plot and character, it is in the cinematic visualization of Shakespeare’s imagery that a creative coalescence of the Shakespearean, along with the ‘local’ occurs. The present paper seeks to offer some notable (it is too difficult to document and discuss all) adaptations of Macbeth . The focus would be to provide introductory information- name of the film, country, language, year of release, the director, star-cast and the critical reception of the adaptation among audiences. -

Cahiers Élisabéthains a Biannual Journal of English Renaissance Studies

Cahiers Élisabéthains A Biannual Journal of English Renaissance Studies General Editors: Yves Peyré & Charles Whitworth Revue fondée en/Founded in 1972 (ISSN 0184-7678) & publiée par/ published by L’INSTITUT DE RECHERCHES SUR LA RENAISSANCE, L’ÂGE CLASSIQUE ET LES LUMIÈRES (IRCL) UMR 5186 du CNRS, Université Paul Valéry, Route de Mende, 34199 Montpellier, France A PLAY, FILM AND OPERA REVIEW INDEX TO Cahiers Élisabéthains 1-70: CORIOLANUS (compiled by Janice Valls-Russell, Managing Editor, IRCL) Issue no. Pages Coriolanus, directed by Terry Hands for the Royal Shakespeare Company, The Aldwych Theatre, London, 9 June 1978 (Jean VACHÉ) 14 111-12 Coriolanus, directed by Terry Hands for the Royal Shakespeare Company, Théâtre National de l’Odéon, Paris, 3-8 April 1979 (Frédéric FERNEY) 16 97-99 Coriolanus, directed by Brian Bedford for the Stratford Shakespeare Festival, Stratford, Ontario, 16 June 1981 (Charles HAINES) 20 119-20 Coriolan, directed by Bernard Sobel, Théâtre de Gennevilliers, 3 March 1983 (Leonore LIEBLEIN) 24 96-97 Coriolanus, produced by Shaun Sutton and directed by Elijah Moshinsky, BBC Shakespeare, BBC 2, 21 April 1984 (G. M. PEARCE) 26 96-98 The Roman Tragedies. 60 mn video cassette, based on Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, and Coriolanus. Written and presented by David Whitworth, produced and directed by Noël Hardy (G. M. PEARCE) 28 87-88 Coriolanus, directed by Peter Hall, National Theatre, London, 8 May 1985 (G. M. PEARCE) 28 93-95 Coriolanus, directed by Jane Howell, The Young Vic, London, 27 May 1989 (Peter J. SMITH) 36 97-98 Coriolanus, directed by Terry Hands for the Royal Shakespeare Company, Barbican Main Theatre, London, 2 May 1990 (Jill PEARCE) 38 95-96 Coriolanus, directed by Michael Bogdanov for the English Shakespeare Company, Theatre Royal, Nottingham, 12 December 1990 (Peter J. -

Chicago Shakespeare in the Parks Tour Into Their Neighborhoods Across the Far North, West, and South Sides of the City

ANNOUNCING OUR 2018/2019 SEASON —The Merry Wives of Windsor Explosive, Pulitzer Prize-winning drama. Shakespeare’s tale of magic and mayhem—reimagined. The “76-trombone,” Tony-winning musical The Music Man. And so much more! 5-play Memberships start at just $100. We’re Only Alive For A Short Amount Of Time | How To Catch Creation | Sweat The Winter’s Tale | The Music Man | Lady In Denmark | Twilight Bowl | Lottery Day GoodmanTheatre.org/1819Season 312.443.3800 2018/2019 Season Sponsors MACBETH Contents Chicago Shakespeare Theater 800 E. Grand on Navy Pier On the Boards 10 Chicago, Illinois 60611 A selection of notable CST events, plays, and players 312.595.5600 www.chicagoshakes.com Conversation with the Directors 14 ©2018 Chicago Shakespeare Theater All rights reserved. Cast 23 ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CARL AND MARILYNN THOMA ENDOWED CHAIR: Barbara Gaines EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Playgoer's Guide 24 Criss Henderson PICTURED: Ian Merrill Peakes Profiles 26 and Chaon Cross COVER PHOTO BY: Jeff Sciortino ABOVE PHOTO BY: joe mazza A Scholar’s Perspective 40 The Basic Program of Liberal Education for Adults is a rigorous, non- Part of the John W. and Jeanne M. Rowe credit liberal arts program that draws on the strong Socratic tradition Inquiry and Exploration Series at the University of Chicago. There are no tests, papers, or grades; you will instead delve into the foundations of Western political and social thought through instructor-led discussions at our downtown campus and online. EXPLORE MORE AT: graham.uchicago.edu/basicprogram www.chicagoshakes.com 5 Welcome DEAR FRIENDS, When we first imagined The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare and the artistic capacity inherent in its flexible design, we hoped that this new venue would invite artists to dream big as they approached Shakespeare’s work. -

Rina Mahoney

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Rina Mahoney Talent Representation Telephone Elizabeth Fieldhouse +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer HAMLET Gertrude Damian Cruden Shakespeares Rose Theatre, York TWELFTH NIGHT Maria Joyce Branagh Shakespeares Rose Theatre, York DEATH OF A SALESMAN The Woman Sarah Frankcom Royal Exchange Theatre Shakespeare's Rose MACBETH Lady Macduff/Young Siward Damian Cruden Theatre/Lunchbox Productions Shakespeare's Rose A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM Peter Quince Juliet Forster Theatre/Lunchbox Productions THE PETAL AND THE ORCHID Kathryn Cat Robey Underexposed Theatre THE SECRET GARDEN Ayah/Dr Bres Liz Stevenson Theatre by the Lake ROMEO AND JULIET Nurse Justin Audibert RSC (BBC Live) MACBETH Witch 2 Justin Audibert RSC (BBC Live) ZILLA Rumani Joyce Branagh The Gap Project Duke of Venice/Portia's THE MERCHANT OF VENICE Polly Findlay RSC Servant OTHELLO Ensemble/Emillia Understudy Iqbal Khan RSC Birmingham Repertory FADES, BRAIDS AND KEEPING IT REAL Eva Antionette Lecester Theatre/Sharon Foster Productions CALCUTTA KOSHER Maki Janet Steel Arcola/Kali ARE WE NEARLY THERE YET? Various Matthew Lloyd Wilton's Music Hall FLINT STREET NATIVITY The Angel Matthew Lloyd Hull Truck Theatre MATCH Jasmin Jenny Stephens Hearth UNWRAPPED FESTIVAL Various Gwenda Hughes Birmingham Repertory Theatre HAPPY NOW Bea Matthew Lloyd Hull Truck Theatre Company MIRIAM ON 34TH STREET Kathy Jenny Stephens Something & Nothing -

Chicago Shakespeare Theater Is Chicago’S Professional Theater Dedicated Timeline 12 to the Works of William Shakespeare

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 1 Art That Lives 2 Bard’s Bio 3 The First Folio 4 Shakespeare’s England 4 The English Renaissance Theater 6 Barbara Gaines Criss Henderson Courtyard-style Theater 8 Artistic Director Executive Director On the Road: A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater dedicated Timeline 12 to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” In its Elizabethan-style courtyard theater, 500 seats on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows separating the farthest Dramatis Personae 14 seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also features a flexible 180-seat The Story 15 black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Center, and a Shakespeare Act-by-Act Synopsis 15 specialty bookstall. Something Borrowed, Something New: Shakespeare’s Sources 17 Now in its twenty-eighth season, the Theater has produced nearly the entire 1606 and All That 18 Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends Well, Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare, Tragedy and Us 20 As You Like It, The Comedy of Errors, Cymbeline, Hamlet, Henry IV A Scholar’s Perspective: Hereafter 21 Parts 1 and 2, Henry V, Henry VI Parts 1, 2 and 3, Henry VIII, Julius What the Critics Say 23 Caesar, King John, King Lear, Love’s Labor’s Lost, Macbeth, Measure Why Teach Macbeth? 34 for Measure, The Merchant of Venice, The Merry Wives of Windsor, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, Othello, Pericles, A Play Comes to Life Richard II, Richard III, Romeo and Juliet, The Taming of the Shrew, A Look Back at Macbeth in Performance 38 The Tempest, Timon of Athens, Troilus and Cressida, Twelfth Night, Dueling Macbeths Erupt in Riots! 42 The Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and The A Conversation with the Director 43 Winter’s Tale. -

The Tragedy of Macbeth William Shakespeare 1564–1616

3HAKESPEARean DrAMA The TRAGedy of Macbeth Drama by William ShakESPEARE READING 2B COMPARe and CONTRAST the similarities and VIDEO TRAILER KEYWORD: HML12-346A DIFFERENCes in classical plaYs with their modern day noVel, plaY, or film versions. 4 EVALUAte how THE STRUCTURe and elements of drAMA -EET the AUTHOR CHANGe in the wORKs of British DRAMAtists across literARy periods. William ShakESPEARe 1564–1616 In 1592—the first time William TOAST of the TOwn In 1594, Shakespeare Shakespeare was recognized as an actor, joined the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the poet, and playwright—rival dramatist most prestigious theater company in Robert Greene referred to him as an England. A measure of their success was DId You know? “upstart crow.” Greene was probably that the theater company frequently jealous. Audiences had already begun to performed before Queen Elizabeth I and William ShakESPEARe . notice the young Shakespeare’s promise. her court. In 1599, they were also able to • is oFten rEFERRed To as Of course, they couldn’t have foreseen purchase and rebuild a theater across the “the Bard”—an ancienT Celtic term for a poet that in time he would be considered the Thames called the Globe. greatest writer in the English language. who composed songs The company’s domination of the ABOUT heroes. Stage-Struck Shakespeare probably London theater scene continued • INTRODUCed more than arrived in London and began his career after Elizabeth’s Scottish cousin 1,700 new wORds inTo in the late 1580s. He left his wife, Anne James succeeded her in 1603. James the English languagE. Hathaway, and their three children behind became the patron, or chief sponsor, • has had his work in Stratford. -

Bernard Lloyd

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Phone: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 Email: [email protected] Bernard Lloyd Location: London Appearance: White Height: 5'9" (175cm) Other: Equity Weight: 12st. 2lb. (77kg) Eye Colour: Brown Playing Age: Over 70 years Hair Colour: Grey Stage 2015, Stage, Arnold, Now Is Not The End, Arcola Theatre, Katie Lewis 2014, Stage, Cardinal Ottaviani, The Last Confession, Trimumph Entertainment / World Tour, Jonathan Church 2011, Stage, Duke of Gloucester, King Lear, West Yorkshire Playhouse, Ian Brown 2007, Stage, Villot, The Last Confession, Theatre Royal Haymarket, David Jones 2006, Stage, Vincent Crummles, Nicholas Nickleby, Chichester Festival Theatre, Jonathan Church & Philip Franks 2006, Stage, Harry Morrison, Bishop of Putney, Pravda, Chichester Festival Theatre & Birmingham Rep, Jonathan Church 2001, Stage, Johnson Over Jordan, West Yorkshire Playhouse, Jude Kelly 2000, Stage, Chas, Still Time, Manchester Royal Exchange, Sarah Frankcom 1998, Stage, Tom Connolly, Give Me Your Answer Do, Lyric Theatre Belfast, Ben Twist 1998, Stage, Chaplain, Mother Courage, Manchester Contact Theatre, Ben Twist 1997, Stage, Quince, A Midsummer Night's Dream, Royal Shakespeare Company, Adrian Noble 1996, Stage, Sir Toby Belch, Twelfth Night, Royal Shakespeare Company, Ian Judge 1995, Stage, Aunt Augusta, Travels With My Aunt, York Theatre Royal, John Doyle 1994, Stage, Don Fernando, Le Cid, Royal National Theatre, Jonathan Kent Stage, Marley's Ghost, A -

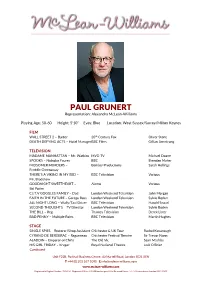

PAUL GRUNERT Representation: Alexandra Mclean-Williams

PAUL GRUNERT Representation: Alexandra McLean-Williams Playing Age: 50-60 Height: 5’10” Eyes: Blue Location: West Sussex/Surrey/Milton Keynes FILM WALL STREET 2 – Barber 20th Century Fox Oliver Stone DEATH DEFYING ACTS – Hotel Manager BBC Films Gillian Armstrong TELEVISION MADAME MANHATTAN – Mr. Watkins MVD TV Michael Doane SPOOKS – Nicholas Faures BBC Brendan Maher MIDSOMER MURDERS – Bentley Productions Sarah Hellings Freddie Greenaway THERE’S A VIKING IN MY BED – BBC Television Various Mr. Bradshaw GOODNIGHT SWEETHEART – Alamo Various Sid Potter C.I.T.V GOGGLES FAMILY – Dad London Weekend Television John Morgan FAITH IN THE FUTURE – Garage Boss London Weekend Television Sylvie Boden ALL NIGHT LONG – Wally/Taxi Driver BBC Television Harold Snoad SECOND THOUGHTS – TV Director London Weekend Television Sylvie Boden THE BILL – Reg Thames Television Derek Lister BAD PENNY – Multiple Roles BBC Television Martin Hughes STAGE SINGLE SPIES – Restorer/Shop Assistant Chichester & UK Tour Rachel Kavanaugh CYRANO DE BERGERAC – Ragueneau Chichester Festival Theatre Sir Trevor Nunn ALADDIN – Emperor of China The Old Vic Sean Mathias HIS GIRL FRIDAY – Kruger Royal National Theatre Jack O’Brian Continued Unit F22B, Parkhall Business Centre, 40 Martell Road, London SE21 8EN T +44 (0) 203 567 1090 E [email protected] www.mclean-williams.com Registered in England Number: 7432186 Registered Office: C/O William Sturgess & Co, Burwood House, 14 - 16 Caxton Street, London SW1H 0QY PAUL GRUNERT continued LOVE’S LABOUR’S LOST – Sir Nathaniel Royal National -

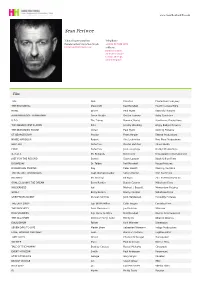

Sean Pertwee

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Sean Pertwee Talent Representation Telephone Madeleine Dewhirst & Sian Smyth +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Film Title Role Director Production Company THE RECKONING Moorcroft Neil Marshall Fourth Culture Films HOWL Driver Paul Hyett Starchild Pictures ALAN PARTRIDGE: ALPHA PAPA Steve Stubbs Declan Lowney Baby Cow Films U.F.O. The Tramp Dominic Burns Hawthorne Productions THE MAGNIFICENT ELEVEN Pete Jeremy Wooding Angry Badger Pictures THE SEASONING HOUSE Goran Paul Hyett Sterling Pictures ST GEORGE'S DAY Proctor Frank Harper Elstree Productions NAKED HARBOUR Robert Aku Louhimies First Floor Productions WILD BILL Detective Dexter Fletcher 20Ten Media FOUR Detective John Langridge Oh My! Productions 4, 3, 2, 1 Mr. Richards Noel Clark Unstoppable Entertainment JUST FOR THE RECORD Sensei Steve Lawson Black & Blue Films DOOMSDAY Dr. Talbot Neil Marshall Rogue Pictures DANGEROUS PARKING Ray Peter Howitt Flaming Pie Films THE MUTANT CHRONICLES Capt. Nathan Rooker Simon Hunter First Foot Films BOTCHED Mr. Groznyi Kit Ryan Zinc Entertainment Inc. GOAL! 2: LIVING THE DREAM Barry Rankin Danny Cannon Milkshake Films WILDERNESS Jed Michael J. Bassett Momentum Pictures GOAL! Barry Rankin Danny Cannon Milkshake Films GREYFRIARS BOBBY Duncan Smithie John Henderson Piccadilly Pictures THE LAST DROP Sgt. Bill McMillan Colin Teague Carnaby Films THE PROPHECY Dani Simionescu Joel Soisson Miramax DOG SOLDIERS Sgt. Harry G. Wells Neil Marshall Kismet Entertainment THE 51st STATE Detective Virgil Kane Ronny Yu Alliance Atlantis EQUILIBRIUM Father Kurt Wimmer Dimension SEVEN DAYS TO LIVE Martin Shaw Sebastian Niemann Indigo Productions LOVE, HONOUR AND OBEY Sean Dominic Anciano Fugitive Films TUBE TALES Driver Charles McDougal Horsepower SOLDIER Mace Paul Anderson Warner Bros.