Ring-Tailed Lemur Husbandry Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7 Gibbon Song and Human Music from An

Gibbon Song and Human Music from an 7 Evolutionary Perspective Thomas Geissmann Abstract Gibbons (Hylobates spp.) produce loud and long song bouts that are mostly exhibited by mated pairs. Typically, mates combine their partly sex-specific repertoire in relatively rigid, precisely timed, and complex vocal interactions to produce well-patterned duets. A cross-species comparison reveals that singing behavior evolved several times independently in the order of primates. Most likely, loud calls were the substrate from which singing evolved in each line. Structural and behavioral similarities suggest that, of all vocalizations produced by nonhuman primates, loud calls of Old World monkeys and apes are the most likely candidates for models of a precursor of human singing and, thus, human music. Sad the calls of the gibbons at the three gorges of Pa-tung; After three calls in the night, tears wet the [traveler's] dress. (Chinese song, 4th century, cited in Van Gulik 1967, p. 46). Of the gibbons or lesser apes, Owen (1868) wrote: “... they alone, of brute Mammals, may be said to sing.” Although a few other mammals are known to produce songlike vocalizations, gibbons are among the few mammals whose vocalizations elicit an emotional response from human listeners, as documented in the epigraph. The interesting questions, when comparing gibbon and human singing, are: do similarities between gibbon and human singing help us to reconstruct the evolution of human music (especially singing)? and are these similarities pure coincidence, analogous features developed through convergent evolution under similar selective pressures, or the result of evolution from common ancestral characteristics? To my knowledge, these questions have never been seriously assessed. -

Verreaux's Sifaka (Propithecus Verreauxi) and Ring- Tailed Lemur

MADAGASCAR CONSERVATION & DEVELOPMENT VOLUME 8 | ISSUE 1 — JULY 2013 PAGE 21 ARTICLE http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mcd.v8i1.4 Verreaux’s sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi) and ring- tailed lemur (Lemur catta) endoparasitism at the Bezà Mahafaly Special Reserve James E. LoudonI,II, Michelle L. SautherII Correspondence: James E. Loudon Department of Anthropology, University of Colorado-Boulder Boulder, CO 80309-0233, U.S.A. E - mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT facteurs comportementaux lors de l’acquisition et l’évitement As hosts, primate behavior is responsible for parasite avoid- des parasites transmis par voie orale en comparant le compor- ance and elimination as well as parasite acquisition and trans- tement des Propithèques de Verreaux (Propithecus verreauxi) et mission among conspecifics. Thus, host behavior is largely des Makis (Lemur catta) se trouvant dans la Réserve Spéciale du responsible for the distribution of parasites in free - ranging Bezà Mahafaly (RSBM) à Madagascar. Deux groupes de chacune populations. We examined the importance of host behavior in de ces espèces étaient distribués dans une parcelle protégée et acquiring and avoiding parasites that use oral routes by compar- deux autres dans des forêts dégradées par l’activité humaine. ing the behavior of sympatric Verreaux’s sifaka (Propithecus L’analyse de 585 échantillons fécaux a révélé que les Makis verreauxi) and ring - tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) inhabiting the de la RSBM étaient infestés par six espèces de nématodes et Bezà Mahafaly Special Reserve (BMSR) in Madagascar. For trois espèces de parasites protistes tandis que les Propithèques each species, two groups lived in a protected parcel and two de Verreaux ne l’étaient que par deux espèces de nématodes. -

What Are Mouse Lemurs? in the WILD in CAPTIVITY

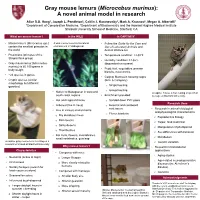

Gray mouse lemurs (Microcebus murinus): A novel animal model in research Alice S.O. Hong¹, Jozeph L. Pendleton², Caitlin J. Karanewsky², Mark A. Krasnow², Megan A. Albertelli¹ ¹Department of Comparative Medicine, ²Department of Biochemistry and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA What are mouse lemurs? In the WILD In CAPTIVITY • Mouse lemurs (Microcebus spp.) A wild mouse lemur in its natural • Follow the Guide for the Care and contain the smallest primates in environment in Madagascar. Use of Laboratory Animals and the world Animal Welfare Act • Prosimians (primates of the • Temperature condition: 74-80ºF Strepsirrhine group) • Humidity condition: 44-65% • Gray mouse lemur (Microcebus (dependent on season) murinus) is 80-100 grams in body weight. • Food: fruit, vegetables, primate biscuits, meal worms • ~24 species in genus • Caging: Marmoset housing cages • Cryptic species (similar (Britz & Company) morphology but different o genetics) Single housing o Group housing • Native to Madagascar in west and A captive mouse lemur resting on perch in south coast regions • Enrichment provided: its cage at Stanford University. • Hot and tropical climate o Sanded down PVC pipes Research Uses • Arboreal (live in trees) o External and cardboard nest boxes • Research in animal’s biological • Live in various environments: and physiological characteristics o Fleece blankets o Dry deciduous trees o Reproductive biology o Rain forests o Torpor, food restriction o Spiny deserts o Manipulation of photoperiod o Thornbushes o Sex differences with behavior • Eat fruits, flowers, invertebrates, o Metabolism small vertebrates, gum/sap A captive gray mouse lemur resting on a o Genetic variation researcher’s hand at Stanford University. -

Using Molecular Techniques to Determine the Provenience of Illegal Ring-Tailed Lemur (Lemur Catta) Pets

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 1-5-2018 Combatting the Illegal Pet Trade: Using Molecular Techniques to Determine the Provenience of Illegal Ring-Tailed Lemur (Lemur catta) Pets Jessica Knierim CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/271 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Combatting the Illegal Pet Trade: Using Molecular Techniques to Determine the Provenience of Illegal Ring-Tailed Lemur (Lemur catta) Pets by Jessica Knierim Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Animal Behavior and Conservation, Hunter College The City University of New York 2017 Thesis Sponsor: December 18, 2017 Dr. Andrea Baden Date Signature December 18, 2017 Dr. Tara Clarke Date Signature of Second Reader COMBATTING THE ILLEGAL PET TRADE IN L. CATTA ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ iii List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. -

Lemurs, Monkeys & Apes, Oh

Lemurs, Monkeys & Apes, Oh My! Audience Activity is designed for ages 12 and up Goal Students will be able to understand the differences between primate groups Objective • To use critical thinking skills to identify different primate groups • To learn what makes primates so unique. Conservation Message Many of the world’s primates live in habitats that are currently being threatened by human activities. Most of these species live in rainforests in Asia, South America and Africa, all these places share a similar threat; unstainable agriculture and climate change. In the last 20 years, chimpanzee and ring-tailed lemur populations have declined by 90%. There are some easy things we can do to help these animals! Buying sustainable wood and paper products, recycling any items you can, spreading the word about the issues and supporting local zoos and aquariums. Background Information There are over 300 species of primates. Primates are an extremely diverse group of animals and cover everything from marmosets to lorises to gorillas and chimpanzees. Many people believe that all primates are monkeys, however, this is incorrect. There are many differences between primate species. Primates are broken into prosimians (lemurs, tarsius, bushbabies and lorises), monkeys (Old and New World) and apes (gibbons, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos). Prosimians are primarily tree-dwellers. This group includes species such as lemurs, tarsius, bushbabies and lorises. They have longer snouts than other primates, a wet nose and a good sense of smell. They have smaller brains, large eyes that are adapted for night vision, and long tails that are not prehensile, meaning they are not able to grab onto items with their tails. -

Trichromatic Vision in Prosimians

brief communications Vision Diurnal prosimians have a functional auto- The X-linked opsin polymorphism and somal opsin gene and a functional X-linked the autosomal opsin gene should enable a Trichromatic vision in opsin gene, but so far no polymorphism heterozygous female lemur to produce three at either locus has been found2. The spec- classes of opsin cone, making it trichromat- prosimians l tral wavelength-sensitivity maxima ( max) ic in the same way as many New World Trichromatic vision in primates is achieved of opsins from four lemurs from each of monkeys. Behavioural and spectral studies by three genes encoding variants of the pho- two species have been measured by using of heterozygous female lemurs have yet to topigment opsin that respond individually electroretinographic flicker photometry2: demonstrate trichromacy, but the possibili- to short, medium or long wavelengths of only a single class of X-linked opsin was ty is supported by anatomical and physio- l light. It is believed to have originated in detected, with max at about 543 nm, indi- logical findings showing many similarities simians because so far prosimians (a more cating that prosimians have no polymor- in the organization of prosimian and simi- primitive group that includes lemurs and phism at the X-linked opsin locus and are an visual systems7, such as the lorises) have been found to have only mono- at best dichromatic2. But because this con- parvocellular (P-cell) system, which is spe- chromatic or dichromatic vision1–3. But our clusion was based on a small sample size, cialized for trichromacy by mediating red– analysis of the X-chromosome-linked opsin we studied 20 species representing the green colour opponency8. -

And Ring-Tailed (Lemur Catta) Inhabiting the Beza Mahafaly Special Reserve

Dietary patterns and stable isotope ecology of sympatric Verreaux’s sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi) and ring-tailed (Lemur catta) inhabiting the Beza Mahafaly Special Reserve By Nora W. Sawyer July 2020 Director of Thesis: Dr. James E. Loudon Major Department: Anthropology Primatologists have long been captivated by the study of the inter-relationships between nonhuman primate (NHP) biology, behavior, and ecology. To understand these interplays, primatologists have developed a broad toolkit of methodologies including behavioral observations, controlled studies of diet and physiology, nutritional analyses of NHP food resources, phylogenetic reconstructions, and genetics. Relatively recently, primatologists have begun employing stable isotope analyses to further our understanding of NHPs in free-ranging settings. Stable carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotope values are recorded in the tissues and excreta of animals and reflect their dietary patterns. This study incorporates the δ13C and δ15N fecal values of the ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) and Verreaux’s sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi) that inhabited the Beza Mahafaly Special Reserve in southwest Madagascar. The statistical program R was used to measure the impacts of anthropogenic disturbance and season (wet vs. dry) on the δ13C and δ15N fecal values of these primates. Furthermore, this project attempted to measure the accuracy of using feeding observations in comparison to stable isotope analysis to infer diet. In order to do so, this project integrated the feeding observations of L. catta and P. verreauxi with the δ13C and δ15N values of the plants they ate and compared these vales to their δ13C and δ15N fecal values. Based on feeding observations and δ13C and δ15N plant values, an equation was developed to predict the fecal δ13C and δ15N values of the ring-tailed lemurs and Verreaux’s sifaka. -

Taxonomic Revision of Mouse Lemurs (Microcebus) in the Western Portions of Madagascar

International Journal of Primatology, Vol. 21, No. 6, 2000 Taxonomic Revision of Mouse Lemurs (Microcebus) in the Western Portions of Madagascar Rodin M. Rasoloarison,1 Steven M. Goodman,2 and Jo¨ rg U. Ganzhorn3 Received October 28, 1999; revised February 8, 2000; accepted April 17, 2000 The genus Microcebus (mouse lemurs) are the smallest extant primates. Until recently, they were considered to comprise two different species: Microcebus murinus, confined largely to dry forests on the western portion of Madagas- car, and M. rufus, occurring in humid forest formations of eastern Madagas- car. Specimens and recent field observations document rufous individuals in the west. However, the current taxonomy is entangled due to a lack of comparative material to quantify intrapopulation and intraspecific morpho- logical variation. On the basis of recently collected specimens of Microcebus from 12 localities in portions of western Madagascar, from Ankarana in the north to Beza Mahafaly in the south, we present a revision using external, cranial, and dental characters. We recognize seven species of Microcebus from western Madagascar. We name and describe 3 spp., resurrect a pre- viously synonymized species, and amend diagnoses for Microcebus murinus (J. F. Miller, 1777), M. myoxinus Peters, 1852, and M. ravelobensis Zimmer- mann et al., 1998. KEY WORDS: mouse lemurs; Microcebus; taxonomy; revision; new species. 1De´partement de Pale´ontologie et d’Anthropologie Biologique, B.P. 906, Universite´ d’Antana- narivo (101), Madagascar and Deutsches Primantenzentrum, Kellnerweg 4, D-37077 Go¨ t- tingen, Germany. 2To whom correspondence should be addressed at Field Museum of Natural History, Roosevelt Road at Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60605, USA and WWF, B.P. -

(Lemur Catta) in a Sub-Desert Spiny Forest Habitat at Berenty Reserve, Madagascar

Behavioural Strategies of the Ring-Tailed Lemur (Lemur catta) in a Sub-Desert Spiny Forest Habitat at Berenty Reserve, Madagascar. by Nicholas Wilson Ellwanger B.S., Emory University, 2002 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology Behavioural Strategies of the Ring-Tailed Lemur (Lemur catta) in a Sub-Desert Spiny Forest Habitat at Berenty Reserve, Madagascar. by Nicholas Wilson Ellwanger B.S., Emory University, 2002 Supervisory Committee Dr. Lisa Gould, Supervisor (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Yin Lam, Departmental Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Eric Roth, Departmental Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Laura Cowen, Outside Member (Department of Mathematics and Statistics) ii Supervisory Committee Dr. Lisa Gould, Supervisor (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Yin Lam, Supervisor, Departmental Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Eric Roth, Departmental Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Laura Cowen, Outside Member (Department of Mathematics and Statistics) ABSTRACT In an effort to better understand primate behavioural flexibility and responses to low- biomass habitats, behavioural patterns of ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) living in a xerophytic spiny forest habitat in southern Madagascar were examined. Behavioural data were collected over two months on two separate groups living in two distinctly different habitats: a sub-desert spiny forest and a riverine gallery forest. Data on the following behavioural categories integral to primate sociality were collected: time allocation, anti- predator vigilance, predator sensitive foraging, feeding competition, and affiliative behaviour. L. catta living in the spiny forest habitat differed significantly in many behavioural patterns when compared to L. catta living in the gallery forest. -

14 Primate Introduction

Introduction to Primates For crying out loud, Phil….Can’t you just beat your chest like everyone else? Objectives • What are the approaches to studying primates? • Why is primate conservation important? • Know (memorize) the classification of primates • Locate the geographical distribution of primates • Present an overview of the strepsirhines • What is the haplorhine condition? • What makes tarsiers unique? • How are prosimians, monkeys, apes and humans classified? 1 Approaches to Studying Evolu6on Paleontological: Fossil Record Comparave approach 2 Comparisons " ! Modern human hunters-gatherers e.g., Australian Aborigines, Ainu, Bushmen " ! Social Carnivores (wild dogs, lions, hyenas, ?gers, wolves) " ! Non-human primates 3 1 Primate Studies " ! Non-human primates " ! Reasoning by homology " ! Reasoning by analogy " ! Primatology - study of living as well as deceased primates " ! Distribuon of primates 4 Primate Conservaon The silky sifaka (Propithecus candidus), found only in Madagascar, has been on The World's 25 Most Endangered Primates list since its inception in 2000. Between 100 and 1,000 individuals are left in the wild. 5 Order Primates (approx. 200 species) (1) Tree-shrew; (2) Lemur; (3) Tarsier; (4) Cercopithecoid monKey; (5) Chimpanzee; (6) Australian Aboriginal 6 2 Geographic Distribu?on 7 n ! Nocturnal Terms n ! Diurnal n ! Crepuscular n ! Arboreal n ! Terrestrial n ! Insectivorous n ! Frugivorous 8 Primate Classification(s) 9 3 Classificaon of Primates " ! Two suborders: " ! Prosimii-prosimians (“pre-apes”) " ! Anthropoidea (humanlike) 10 Strepsirhine/Haplorhine 11 Traditional & Alternative Classifications Traditional Alternative 12 4 Tree Shrews Order Scandentia not a primate 13 Prosimians lemurs tarsiers lorises 14 Prosimians XXXXXXXXX 15 5 Lemurs 3 Families " ! 1. Lemuridae (true lemurs) Sifaka (Family " ! 2. -

Evidence from Opsin Genes Rejects Nocturnality in Ancestral Primates

Evidence from opsin genes rejects nocturnality in ancestral primates Ying Tan*†, Anne D. Yoder‡, Nayuta Yamashita§, and Wen-Hsiung Li*¶ *Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago, 1101 East 57th Street, Chicago, IL 60637; †Department of Biology, University of Massachusetts, 100 Morrissey Boulevard, Boston, MA 02125; ‡Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, P.O. Box 208105, 21 Sachem Street, New Haven, CT 06520; and §Department of Cell and Neurobiology, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089 Contributed by Wen-Hsiung Li, August 14, 2005 It is firmly believed that ancestral primates were nocturnal, with Materials and Methods nocturnality having been maintained in most prosimian lineages. For the avahi, genomic DNA was obtained from hair follicles by Under this traditional view, the opsin genes in all nocturnal using a DNA extraction kit (QIAamp DNA mini kit, Qiagen, prosimians should have undergone similar degrees of functional Valencia, CA). For the rest of prosimians, genomic DNA was relaxation and accumulated similar extents of deleterious muta- isolated from tissue samples by using the PureGene kit (Gentra tions. This expectation is rejected by the short-wavelength (S) Systems). Exons 1–5 of the S opsin in each species were amplified opsin gene sequences from 14 representative prosimians. We by the PCR from the genomic DNA. The primers initially used for found severe defects of the S opsin gene only in lorisiforms, but no the fat-tailed dwarf lemur and tarsiers were based on New World defect in five nocturnal and two diurnal lemur species and only monkey S-opsin sequences (11). -

Lemurs Are a Very Special Group of Primates That Are Only Found on the Island of Madagascar

Lemurs are a very special group of primates that are only found on the island of Madagascar. There are over 100 different species of Lemur, many of them are endangered or critically endangered. Lemurs are found in many different habitats and have many different diets, but most are omnivores, eating mostly plants and some insects. Communicate with Smells Lemurs rely heavily on their sense of smell and leave scent markings to communicate. Male Ring-tailed Lemurs will have stink fights, waving their smelly tails at each other. The Little Rock Zoo supports Lemur Love, an organization that helps to protect these endangered species in the wild! Want to Learn more? Check out these links and activities! Lemur Love and Lemur Conservation Network http://www.lemurlove.org/lemurs.html https://www.lemurconservationnetwork.org/why-lemurs/ National Geographic: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/r/ring-tailed-lemur/ https://www.nationalgeographic.org/media/photo-ark-red-ruffed-lemur/ Other: Nat Geo - Lemurs Roam Free on This Ancient Island: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UjSiq53nJBo Duke Lemur Center: https://lemur.duke.edu/discover/meet-the-lemurs/ring-tailed-lemur/ San Diego Zoo: https://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/lemur Each lemur has a role to play in its ecosystem, an animals role, or job, is called its niche. One of the important jobs that Black and White Ruffed Lemurs do is to pollinate flowers! They go from flower to flower, sipping delicious nectar, and in return they spread the flowers pollen, helping to produce seeds and fruit! Cut out the puzzle pieces to make the picture of the Black and White Ruffed Lemur! .