The Development of Coal Trade in the Wollongong District of New South Wales, with Particular Reference to Government and Business, 1849-1889

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Eyre Iron Project Environmental Impact Statement

Central Eyre Iron Project Environmental Impact Statement EIS REFERENCES REFERENCES COPYRIGHT Copyright © Iron Road Limited, 2015 All rights reserved This document and any related documentation is protected by copyright owned by Iron Road Limited. The content of this document and any related documentation may only be copied and distributed for the purposes of section 46B of the Development Act, 1993 (SA) and otherwise with the prior written consent of Iron Road Limited. DISCLAIMER Iron Road Limited has taken all reasonable steps to review the information contained in this document and to ensure its accuracy as at the date of submission. Note that: (a) in writing this document, Iron Road Limited has relied on information provided by specialist consultants, government agencies, and other third parties. Iron Road Limited has reviewed all information to the best of its ability but does not take responsibility for the accuracy or completeness; and (b) this document has been prepared for information purposes only and, to the full extent permitted by law, Iron Road Limited, in respect of all persons other than the relevant government departments, makes no representation and gives no warranty or undertaking, express or implied, in respect to the information contained herein, and does not accept responsibility and is not liable for any loss or liability whatsoever arising as a result of any person acting or refraining from acting on any information contained within it. References A ADS 2014, Adelaide Dolphin Sanctuary, viewed January 2014, http://www.naturalresources.sa.gov.au/adelaidemtloftyranges/coast-and-marine/dolphin-sanctuary. Ainslie, RC, Johnston, DA & Offler, EW 1989, Intertidal communities of Northern Spencer Gulf, South Australia, Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, Adelaide. -

EYRE PENINSULA 9/9/2019 – 14/9/2019 Itinerary

EYRE PENINSULA 9/9/2019 – 14/9/2019 Itinerary Day 1 Monday 9 Sept. Drive to Port Lincoln. 7:30 am start and brief stop in Lipson and Tumby Bay on the way to Lincoln and at Poonindie Mission and church. Other stops in Port Augusta, Whyalla, Cowell etc. Overnight at the modern and luxurious four star four storey Port Lincoln Hotel on the Esplanade. PORT LINCOLN HOTEL/MOTEL DINNER BED & BREAKFAST Day 2 Tuesday 10 Sept. Morning tour to spectacular Whalers Way with side trip to Mikkira Homestead ruins. Admission about $5 to be paid on the day and not included. Afternoon explorations of Port Lincoln, including a drive to the lookout over the bay. PORT LINCOLN HOTEL/MOTEL DINNER BED & BREAKFAST Day 3 Wednesday 11 Sept. We head up the coast and stop in to Coffin Bay. Stop Dutton Bay on way for morning tea. Brief stops at Sheringa and Lake Hamilton and its pioneer cemetery. Lunch stop in Elliston where we take southern coast drive circuit. We travel on to Colton for brief stop at the church and burial site of SA’s first Greek settler. We pass through Venus Bay on our journey to Streaky Bay. We stay at Streaky Bay Hotel Motel right on the esplanade. STREAKY BAY HOTEL/MOTEL DINNER, BED & BREAKFAST Day 4 Thursday 12 Sept. We explore the town and then drive a circuit from Streaky Bay to Sceale Bay, Point Labatt with its seal colony and then inland to Murphy’s haystacks. We will see Eyre’s memorial near Streak Bay. -

Heavy Metal Contamination in the Northern Spencer Gulf

ENVIRONMENT PROTECTI ON AUTH ORITY Heavy metal contamination in the northern Spencer Gulf—a community summary The northern Spencer Gulf is an important environmental, social and economic region in South Australia. Its vast seagrass meadows, saltmarshes and mangrove forests sustain a diverse aquatic ecosystem. It is a Studies significant nursery and feeding area for a number of commercially important fish and shellfi sh, including King George whiting, southern sea garfi sh, snapper, conducted southern calamari, blue swimmer crabs and king prawns. over a number The aquaculture of yellowtail kingfish is also expanding in the region and ecotourism continues to of decades grow, particularly due to the annual spawning of the Australian giant cuttlefi sh near Whyalla. have shown The northern Spencer Gulf is also an important industrial area, accommodating industries such as the elevated Zinifex lead-zinc smelter at Port Pirie (formerly known as Pasminco) and the OneSteel steelworks at Whyalla. levels of While the industries in the region provide economic benefit to the state, they discharge signifi cant amounts of heavy metals into the air, onto land and metals in the directly to the gulf waters. Studies conducted over a number of decades have upper section shown elevated levels of metals in the upper section of the gulf, particularly in Germein Bay near Port Pirie. of the gulf. Steelworks at Whyalla Port Pirie smelter > heavy metal pollution has affected the diversity of animal life in the region, with a reduction in the number of animals living in seagrass beds near the pollution sources > concentrations of some metals in razorfi sh collected from Germein Bay, near Port Pirie, were found to be Factors affecting the water above food standards; as a result, the collection of quality of the northern marine benthic molluscs is currently prohibited from Spencer Gulf most of Germein Bay. -

Coke Making in the Illawarra : a Talk Given by Don Reynolds

COKE MAKING IN ILLA WARRA A talk given by Don Reynolds to the Society in March 2006. Coke making began in Illawarra in 1874 by Osborne and Ahearn who built a small battery of circular beehive coke ovens on a site just to the south of Wollongong Harbour, that undertalcing only lasted till about 1890. In 1984 the site was exposed by council when carrying out road works just south east of Belmore Basin; the site was examined and recorded by Brian Rogers and then filled in. In 1884 Thomas Bertram opened the Broker's Nose Coal Company in the escarpment behind what is now CorrimaJ; he built a set of 7 beehive coke ovens (presumably of the circular type) on the northern side of Tarrawanna Road, it appears that these ovens only operated spasmodically. The Southern Coal Company (SCC) was formed in the UK to build a coJliery on the southern slopes ofMt Kembla and a railway from the mine to a jetty they were building in an unprotected bay at Five Islands. They also built a large set of modem rectangular beehive coke ovens alongside their railway near where the Commonwealth Steel stainless steel plant was much later built. This coke ovens plant, which was known as the Australian Coke Making Company, went into service in 1888. The coal mine of the SCC immediately ran into problems due to geological disturbances and the mine was abandoned. They negotiated with Thomas Bertram and leased his Corrimal coal mining and railway facilities in order to meet their commitments. The SCC quickly upgraded the Corrimal facility and began to rail coal to their new jetty and coke works. -

There Has Been an Italian Presence in the Riverland Since

1 Building blocks of settlement: Italians in the Riverland, South Australia By Sara King and Desmond O’Connor The Riverland region is situated approximately 200 km. north-east of Adelaide and consists of a strip of land on either side of the River Murray from the South Australian-Victorian border westwards to the town of Morgan. Covering more than 20,000 sq. km., it encompasses the seven local government areas of Barmera, Berri, Loxton, Morgan, Paringa, Renmark and Waikerie.1 The region was first identified as an area of primary production in 1887 when two Canadian brothers, George and William Chaffey, were granted a licence to occupy 101,700 hectares of land at Renmark in order to establish an irrigated horticultural scheme. By 1900 a prosperous settlement had developed in the area for the production of vines and fruit, and during the 1890s Depression other ‘village settlements’ were established down river by the South Australian Government to provide work for the city-based unemployed.2 During the years between the foundation of the villages and the First World War there was intense settlement, especially around Waikerie, Loxton, Berri and Barmera, as the area was opened up and increased in value.3 After World War 1, the SA Government made available new irrigation blocks at Renmark and other localities in the Riverland area to assist the resettlement of more than a thousand returned soldiers. A similar scheme operated in New South Wales, where returned servicemen were offered blocks in Leeton and Griffith, in the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area.4 The period after World War 2 saw further settlement of returned soldiers on fruit blocks in the Riverland and new irrigation areas were developed to cater for this growth. -

Discover South Australia's Eyre Peninsula Day 1. Adelaide

www.drivenow.com.au – helping travellers since 2003 find the best deals on campervan and car rental Discover South Australia’s Eyre Peninsula One of Australia’s lesser explored regions, the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia is home to some of the most stunning coastlines and the Seafood capital of Australia, Port Lincoln, on Boston Bay. This 10 day 1565km tour takes you north from Adelaide to Port Augusta before heading south and looping around the Peninsula. Day 1. Adelaide Collect your campervan in Adelaide today. Even for those who have travelled by campervan before, allow an hour in order to familiarise yourself with the vehicle before you leave the branch. Adelaide is the capital city of South Australia and offers a variety of activities suited to everyone’s tastes. Visit Hahndorf, Australia’s oldest surviving German settlement. The town retains a strong German heritage, transporting you to an entirely new cultural experience. There are plenty of places to try some food, buy some souvenirs and enjoy the history. If you have time, visit the Art Gallery of South Australia to top off your cultural day! Founded in 1881, the gallery is found in the cultural precinct of Adelaide, right next to www.drivenow.com.au – helping travellers since 2003 find the best deals on campervan and car rental the Adelaide Museum and University of Adelaide. The gallery has a collection of over 38,000 works comprising of different nationalities and types. Stay: Adelaide Caravan Park Day 2. Adelaide to Port Pirie Depart this morning and follow the National Highway 1 to the Spencer Highway/ B89 in Bungama. -

Port Pirie Regional Council Interactions Through the City

PORT PIRIE: A Strategic Port Solution for South Australia PORT EXPANSION PROPOSAL Key Features Advantages Initial Estimated Capacity: 20mTPA Capital Cost* • The major advantage of this • The proposed storage area is proposal is that it is highly Rail Loop $25 located east of Port Pirie off of Port flexible and is scalable to Rail Separation $25 Germein Road (Spencer Highway), meet initial and future Train Unloading Facility $50 next to the north-south rail line (and demand Storage Shed (x1) $25 in close proximity to the eastern line • The project can be started at Conveyor to Wharf $18 from Crystal Brook which services lower volumes and the Basic Wharf/Piles $15 the Braemar mining region) and is transhipment approach will Fixed Ship Loader $10 outside the CBD and residential allow it to be expanded Contingencies $15 areas of the City. beyond 20mtpa. Total Cost $183m • It features a 4km balloon loop for • The lead time to obtain all rail access off of the main north- relevant approvals, construct Transhipping Costs Est. † south line with the potential to have and be operational is 2-3 $2.5/tonne (for 20mTPA) multiple rail lines, within the loop, if years required. *Initial cost estimates are based on x1 • It is in good proximity to the 200,000t storage shed and a single rail • The site will allow for suitable existing freight rail network loop. Both are capable of being unloading facilities with conveyors • The port is capable of expanded beyond this when required taking the materials from the train a for increased capacity. -

SOUTH AUSTRALIA, Statistical Divisions 1010101010101010 10

SOUTH AUSTRALIA, Statistical Divisions CooberCooberCoober PedyPedyPedy 3535 NorthernNorthern RoxbyRoxbyRoxby DownsDownsDowns WoomeraWoomera CedunaCedunaCeduna PortPortPort AugustaAugustaAugusta 1515 YorkeYorke andand PortPortPort PiriePiriePirie LowerLower NorthNorth 3030 EyreEyre RenmarkRenmarkRenmark 2020 MurrayMurray LandsLands PortPortPort LincolnLincolnLincoln Murray Lands MurrayMurray BridgeBridge 0505 0505 KingscoteKingscoteKingscote AdelaideAdelaide 1010 2525 OuterOuter AdelaideAdelaide SouthSouth EastEast NaracoorteNaracoorteNaracoorte MountMount GambierGambierGambier 0 500 Kilometres 184 ABS • AUSTRALIAN STANDARD GEOGRAPHICAL CLASSIFICATION (ASGC) • 1216.0 • JUL 2006 SOUTH AUSTRALIA, Adelaide Statistical Division P o r t W a GawlerGawlerGawler k GawlerGawlerGawler e f i e l d R d d R h t r o N in a M ElizabethElizabethElizabeth BBaaarrrrkkkeeerrrr IIIIInnnllllleeetttt 05050505 NorthernNorthern AdelaideAdelaide 0505 AdelaideAdelaide BoatingBoating LakeLakeLake 05100510 WesternWestern AdelaideAdelaide 05150515 rrrr RRiiiiivvvveeerrrr rrrrrrreeennnsss RR TTTooorrrrrrreee EasternEastern AdelaideAdelaide y w H c za An GulfGulf StSt VincentVincent P rin c es H w y HappyHappy ValleyValley ReservoirReservoir 05200520 SouthernSouthern AdelaideAdelaide NoarlungaNoarlungaNoarlunga 05100510 Statistical Subdivision WesternWestern AdelaideAdelaide 0505 Statistical Division AdelaideAdelaide 0 20 Kilometres ABS • AUSTRALIAN STANDARD GEOGRAPHICAL CLASSIFICATION (ASGC) • 1216.0 • JUL 2006 185 SOUTH AUSTRALIA, Statistical Subdivisions and Statistical -

CARRAPATEENA PROJECT Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 – Referral of Proposed Action

CARRAPATEENA PROJECT Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 – Referral of Proposed Action March 2017 Carrapateena Project This page has been left blank intentionally. Carrapateena Project / March 2017 Carrapateena Project EPBC Referral of Proposed Mining Lease and Associated Tenements ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Kokatha Aboriginal Corporation The Kokatha People have a direct, unbroken and unique relationship with the land on which the Carrapateena Project is located. OZ Minerals recognises that the sense of place and belonging of the Kokatha People is linked to their identity, creation stories, travel, trade, ceremonies, family and places held sacred. We recognise the deep and ongoing feelings of relationship and attachment they hold for their lands. OZ Minerals acknowledges Kokatha connection to ‘country’, the contribution of Kokatha People to their region and the enduring importance to Kokatha People of values, cultural authority, cultural norms and customary laws. OZ Minerals places great value on our relationship with the Kokatha People. OZ Minerals and Kokatha Aboriginal Corporation seek to work in partnership, as equals, to further develop the Partnering Agreement Nganampa palyanku kanyintjaku ‘Keeping the future good for all of us’. This collaborative agreement encapsulates, recognises and values the ongoing contribution of both partners, and will inform the relationship between Kokatha and OZ Minerals throughout and beyond the development of the Carrapateena Project. Pernatty and Oakden Hills Station Owners The Far North region of South Australia has a long and rich history of pastoralism. The proposed Carrapateena Project is located on Pernatty station and the proposed supporting infrastructure is located within Oakden Hills Station. OZ Minerals recognises the importance of the land to its owners and their operations and acknowledges their cooperation in developing the Project. -

Air Quality Atmosphere Fact Sheet Fact

1 Air Quality Atmosphere Fact Sheet Fact Air Quality Issues Trends Air quality relates to pollution levels in our air. Some of the things we do, such as driving cars, can lead Ambient air quality data must to an increase in the concentration of gases and be long-term and comparable particles released into the air. These can be harmful to humans and the environment. Motor vehicles are to determine accurate trends. the biggest cause of air pollution in South Australia, Current monitoring programs yet we are becoming more and more dependent have not been in place long on these vehicles. Industry, business and activities enough to determine such at home, such as burning wood for heat, are other major causes of air pollution. trends in all cases. The Environment Protection Authority (EPA) monitors air quality in many parts of Adelaide and the rural areas of Mount Gambier, Whyalla, Port Augusta and Port Pirie. This means we can check how our air quality compares with the national standards which have been developed to improve the quality of the air that we breathe. The South Australian Air Quality Management Plan is currently being developed and will be completed in 2009. This plan will help to guide the monitoring and management of air quality in South Australia within the community, industry and government agencies. The potential for increase“ in air pollutants is currently of greatest “ concern in Adelaide. STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT – FACT SHEET 2008 1 Atmosphere Fact Sheet 1 Air Quality What is the Current Air Quality Situation? The National Environment Protection Measure for Air Quality (NEPM) has set health protection standards and goals to be achieved to improve air quality. -

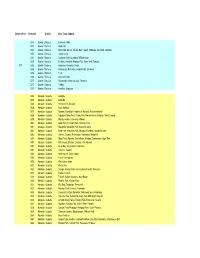

Postcode Database

Delivery Price Postcode District City/ Town/ Suburb 5116 Gawler / Barossa Evanston, Hillier 5117 Gawler / Barossa Angle Vale 5118 Gawler / Barossa Buchfelde, Gawler, Gawler Belt, Hewett, Kalbeeba, Kingsford, Willaston 5350 Gawler / Barossa Sandy Creek 5351 Gawler / Barossa Cockatoo Valley, Lyndoch, Williamstown 5352 Gawler / Barossa Bethany, Krondorf, Rowland Flat, Stone Well, Tanunda $10 5353 Gawler / Barossa Angaston, Keyneton, Sedan 5355 Gawler / Barossa Marananga, Nuriootpa, Seppeltsfield, Stockwell 5356 Gawler / Barossa Truro 5360 Gawler / Barossa Greenock, Nain 5371 Gawler / Barossa Roseworthy, Shea-oak Log, Templers 5372 Gawler / Barossa Freeling 5373 Gawler / Barossa Hamilton, Kapunda 5000 Adelaide / Suburbs Adelaide 5001 Adelaide / Suburbs Adelaide 5005 Adelaide / Suburbs University Of Adelaide 5006 Adelaide / Suburbs North Adelaide 5007 Adelaide / Suburbs Bowden, Brompton, Hindmarsh, Welland, West Hindmarsh 5008 Adelaide / Suburbs Croydon, Devon Park, Dudley Park, Renown Park, Ridleyton, West Croydon 5009 Adelaide / Suburbs Allenby Gardens, Beverley, Kilkenny 5010 Adelaide / Suburbs Angle Park, Ferryden Park, Regency Park 5011 Adelaide / Suburbs Woodville, Woodville Park, Woodville South 5012 Adelaide / Suburbs Athol Park, Mansfield Park, Woodville Gardens, Woodville North 5013 Adelaide / Suburbs Gillman, Ottoway, Pennington, Rosewater, Wingfield 5014 Adelaide / Suburbs Albert Park, Alberton, Cheltenham, Hendon, Queenstown, Royal Park 5015 Adelaide / Suburbs Birkenhead, Ethelton, Glanville, Port Adelaide 5016 Adelaide / Suburbs -

Marine Operations Port Pirie Port Rules

Flinders Ports Pty Ltd Marine Operations Port Pirie Port Rules Uncontrolled if printed Legend denotes Pilotage activity denotes Vessel Traffic Management (scheduling) activity denotes Communications activity denotes Pilot Launch activity denotes Marine Services activity Procedure PRPPI006 Page 1 Issue No. 12 Issue Date: 09/07/2015 I:\HRM\Quality Management\Port Rules\PT PIRIE\PPI - Port Rules ISSUE 12.doc Table of Contents 1. Port Rules ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Scope .................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Authority ............................................................................................................................................ 3 1.4 Powers of Port Management Officers (PMO) ........................................................................................ 4 1.5 Pilotage Constraints ............................................................................................................................ 5 1.5.1 Port Pirie Pilotage Constraints ............................................................................................................................. 5 1.6 Geographic Limits ...............................................................................................................................