Assessment of the Distribution of Plants Endemic to the Lesser Antilles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESPECIES VENEZOLANAS DEL GÉNERO CRITONIA (ASTERACEAE) Species of Critonia Genus in Venezuela (Asteraceae) Carmen E

ACTA BOT. VENEZ. 34 (2): 407-416. 2011 407 ESPECIES VENEZOLANAS DEL GÉNERO CRITONIA (ASTERACEAE) Species of Critonia genus in Venezuela (Asteraceae) Carmen E. BENÍTEZ DE ROJAS Instituto de Botánica Agrícola, Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad Central de Venezuela Apartado 4579, Maracay, estado Aragua [email protected] RESUMEN Critonia P. Browne, de la subfamilia Asteroideae, tribu Eupatorieae, está represen- tado por 40 especies que se extienden desde las Antillas, América Central hasta Argentina. En Venezuela están presentes Critonia eggersii, C. heteroneura, C. morifolia y C. naigua- tensis. Como parte del proyecto “Contribución al estudio de las Asteraceae”, en el presente trabajo se describen y diferencian entre sí, las cuatro especies hasta hoy reportadas para Ve- nezuela, considerándose también el estatus actual de su nomenclatura. Asimismo, se pre- senta una clave para las especies de Critonia en el país y se acompaña cada especie con una ilustración detallada y aspectos fitogeofráficos de las mismas. Palabras clave: Asteraceae, Critonia, Venezuela ABSTRACT Critonia P. Browne, of the subfamily Asteroideae, tribe Eupatorieae, is represented by 40 species extended from the Antillas, Central America to Argentina. In Venezuela C. eggersii, C. heteroneura, C. morifolia and C. naiguatensis are present. As part of the on- going project “Contribution to study of the family Asteraceae”, in the present work, the four species reported to Venezuela are described considering their current nomenclature status. A key for the Critonia species -

Checklist Das Spermatophyta Do Estado De São Paulo, Brasil

Biota Neotrop., vol. 11(Supl.1) Checklist das Spermatophyta do Estado de São Paulo, Brasil Maria das Graças Lapa Wanderley1,10, George John Shepherd2, Suzana Ehlin Martins1, Tiago Egger Moellwald Duque Estrada3, Rebeca Politano Romanini1, Ingrid Koch4, José Rubens Pirani5, Therezinha Sant’Anna Melhem1, Ana Maria Giulietti Harley6, Luiza Sumiko Kinoshita2, Mara Angelina Galvão Magenta7, Hilda Maria Longhi Wagner8, Fábio de Barros9, Lúcia Garcez Lohmann5, Maria do Carmo Estanislau do Amaral2, Inês Cordeiro1, Sonia Aragaki1, Rosângela Simão Bianchini1 & Gerleni Lopes Esteves1 1Núcleo de Pesquisa Herbário do Estado, Instituto de Botânica, CP 68041, CEP 04045-972, São Paulo, SP, Brasil 2Departamento de Biologia Vegetal, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas – UNICAMP, CP 6109, CEP 13083-970, Campinas, SP, Brasil 3Programa Biota/FAPESP, Departamento de Biologia Vegetal, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas – UNICAMP, CP 6109, CEP 13083-970, Campinas, SP, Brasil 4Universidade Federal de São Carlos – UFSCar, Rod. João Leme dos Santos, Km 110, SP-264, Itinga, CEP 18052-780, Sorocaba, SP, Brasil 5Departamento de Botânica – IBUSP, Universidade de São Paulo – USP, Rua do Matão, 277, CEP 05508-090, Cidade Universitária, Butantã, São Paulo, SP, Brasil 6Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana – UEFS, Av. Transnordestina, s/n, Novo Horizonte, CEP 44036-900, Feira de Santana, BA, Brasil 7Universidade Santa Cecília – UNISANTA, R. Dr. Oswaldo Cruz, 266, Boqueirão, CEP 11045-907, -

Epilist 1.0: a Global Checklist of Vascular Epiphytes

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2021 EpiList 1.0: a global checklist of vascular epiphytes Zotz, Gerhard ; Weigelt, Patrick ; Kessler, Michael ; Kreft, Holger ; Taylor, Amanda Abstract: Epiphytes make up roughly 10% of all vascular plant species globally and play important functional roles, especially in tropical forests. However, to date, there is no comprehensive list of vas- cular epiphyte species. Here, we present EpiList 1.0, the first global list of vascular epiphytes based on standardized definitions and taxonomy. We include obligate epiphytes, facultative epiphytes, and hemiepiphytes, as the latter share the vulnerable epiphytic stage as juveniles. Based on 978 references, the checklist includes >31,000 species of 79 plant families. Species names were standardized against World Flora Online for seed plants and against the World Ferns database for lycophytes and ferns. In cases of species missing from these databases, we used other databases (mostly World Checklist of Selected Plant Families). For all species, author names and IDs for World Flora Online entries are provided to facilitate the alignment with other plant databases, and to avoid ambiguities. EpiList 1.0 will be a rich source for synthetic studies in ecology, biogeography, and evolutionary biology as it offers, for the first time, a species‐level overview over all currently known vascular epiphytes. At the same time, the list represents work in progress: species descriptions of epiphytic taxa are ongoing and published life form information in floristic inventories and trait and distribution databases is often incomplete and sometimes evenwrong. -

Hybridization in Compositae

Hybridization in Compositae Dr. Edward Schilling University of Tennessee Tennessee – not Texas, but we still grow them big! [email protected] Ayres Hall – University of Tennessee campus in Knoxville, Tennessee University of Tennessee Leucanthemum vulgare – Inspiration for school colors (“Big Orange”) Compositae – Hybrids Abound! Changing view of hybridization: once consider rare, now known to be common in some groups Hotspots (Ellstrand et al. 1996. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA 93: 5090-5093) Comparison of 5 floras (British Isles, Scandanavia, Great Plains, Intermountain, Hawaii): Asteraceae only family in top 6 in all 5 Helianthus x multiflorus Overview of Presentation – Selected Aspects of Hybridization 1. More rather than less – an example from the flower garden 2. Allopolyploidy – a changing view 3. Temporal diversity – Eupatorium (thoroughworts) 4. Hybrid speciation/lineages – Liatrinae (blazing stars) 5. Complications for phylogeny estimation – Helianthinae (sunflowers) Hybrid: offspring between two genetically different organisms Evolutionary Biology: usually used to designated offspring between different species “Interspecific Hybrid” “Species” – problematic term, so some authors include a description of their species concept in their definition of “hybrid”: Recognition of Hybrids: 1. Morphological “intermediacy” Actually – mixture of discrete parental traits + intermediacy for quantitative ones In practice: often a hybrid will also exhibit traits not present in either parent, transgressive Recognition of Hybrids: 1. Morphological “intermediacy” Actually – mixture of discrete parental traits + intermediacy for quantitative ones In practice: often a hybrid will also exhibit traits not present in either parent, transgressive 2. Genetic “additivity” Presence of genes from each parent Recognition of Hybrids: 1. Morphological “intermediacy” Actually – mixture of discrete parental traits + intermediacy for quantitative ones In practice: often a hybrid will also exhibit traits not present in either parent, transgressive 2. -

Artículo Original

SAGASTEGUIANA 4(2): 73 - 106. 2016 ISSN 2309-5644 ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL CATÁLOGO DE ASTERACEAE DE LA REGIÓN LA LIBERTAD, PERÚ CATALOGUE OF THE ASTERACEAE OF LA LIBERTAD REGION, PERU Eric F. Rodríguez Rodríguez1, Elmer Alvítez Izquierdo2, Luis Pollack Velásquez2, Nelly Melgarejo Salas1 & †Abundio Sagástegui Alva1 1Herbarium Truxillense (HUT), Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, Trujillo, Perú. Jr. San Martin 392. Trujillo, PERÚ. [email protected] 2Departamento Académico de Ciencias Biológicas, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Nacional de Trujillo. Avda. Juan Pablo II s.n. Trujillo, PERÚ. RESUMEN Se da a conocer un catálogo de 455 especies y 163 géneros de la familia Asteraceae existentes en la región La Libertad, Perú. Se incluyen a 148 taxones endémicos y 24 especies cultivadas. El estudio estuvo basado en la revisión de material depositado en los herbarios: F, HUT y MO, salvo indicación contraria. Las colecciones revisadas son aquellas efectuadas en las diversas expediciones botánicas por personal del herbario HUT a través de su historia (1941-2016). Asimismo, en la determinación taxonómica de especialistas, y en la contrastación con las especies documentadas en estudios oficiales para esta región. El material examinado para cada especie incluye la distribución geográfica según las provincias y altitudes, el nombre vulgar si existiera, el ejemplar tipo solamente del material descrito para la región La Libertad, signado por el nombre y número del colector principal, seguido del acrónimo del herbario donde se encuentra depositado; así como, el estado actual de conservación del taxón sólo en el caso de los endemismos. La información presentada servirá para continuar con estudios taxonómicos, ecológicos y ambientales de estos taxa. -

PHYLOGENY, ADAPTIVE RADIATION, and HISTORICAL BIOGEOGRAPHY of BROMELIACEAE INFERRED from Ndhf SEQUENCE DATA

Aliso 23, pp. 3–26 ᭧ 2007, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden PHYLOGENY, ADAPTIVE RADIATION, AND HISTORICAL BIOGEOGRAPHY OF BROMELIACEAE INFERRED FROM ndhF SEQUENCE DATA THOMAS J. GIVNISH,1 KENDRA C. MILLAM,PAUL E. BERRY, AND KENNETH J. SYTSMA Department of Botany, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, USA 1Corresponding author ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Cladistic analysis of ndhF sequences identifies eight major bromeliad clades arranged in ladderlike fashion. The traditional subfamilies Tillandsioideae and Bromelioideae are monophyletic, but Pitcair- nioideae are paraphyletic, requiring the description of four new subfamilies, recircumscription of Pit- cairnioideae and Navioideae, the sinking of Ayensua, and description of the new genus Sequencia. Brocchinioideae are basalmost, followed by Lindmanioideae, both restricted to the Guayana Shield. Next is an unresolved trichotomy involving Hechtioideae from Central America, Tillandsioideae, and the remaining bromeliads in subfamilies Navioideae, Pitcairnioideae, Puyoideae, and Bromelioideae. Bromeliads arose as C3 terrestrial plants on moist infertile sites in the Guayana Shield roughly 70 Mya, spread centripetally in the New World, and reached tropical West Africa (Pitcairnia feliciana) via long-distance dispersal about 10 Mya. Modern lineages began to diverge from each other 19 Mya and invaded drier areas in Central and South America beginning 15 Mya, coincident with a major adaptive radiation involving the repeated evolution of epiphytism, CAM photosynthesis, impounding leaves, several features of leaf/trichome anatomy, and accelerated diversification at the generic level. This ‘‘bromeliad revolution’’ occurred after the uplift of the northern Andes and shift of the Amazon to its present course. Epiphytism may have accelerated speciation by increasing ability to colonize along the length of the Andes, while favoring the occupation of a cloud-forest landscape frequently dissected by drier valleys. -

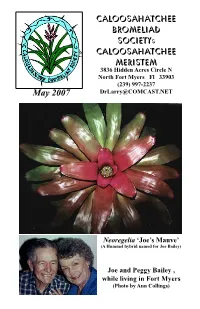

May 2007 [email protected]

CALOOSAHATCHEE BROMELIAD SOCIETY’s CALOOSAHATCHEE MERISTEM 3836 Hidden Acres Circle N North Fort Myers Fl 33903 (239) 997-2237 May 2007 [email protected] Neoregelia ‘Joe’s Mauve’ (A Hummel hybrid named for Joe Bailey) Joe and Peggy Bailey , while living in Fort Myers (Photo by Ann Collings) CALOOSAHATCHEE BROMELIAD SOCIETY OFFICERS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE PRESIDENT Steve Hoppin ([email protected]) VICE-PRESIDENT Tom Foley ([email protected]) SECRETARY Chuck Ray ([email protected]) TREASURER Betty Ann Prevatt ([email protected]) PAST-PRESIDENT Dianne Molnar ([email protected]) STANDING COMMITTEES CHAIRPERSONS NEWSLETTER EDITOR Larry Giroux ([email protected]) FALL SHOW CHAIR Steve Hoppin ([email protected]) FALL SALES CHAIR Brian Weber ([email protected]) FALL SHOW Co-CHAIR Betty Ann Prevatt ([email protected]) PROGRAM CHAIRPERSONS Debbie Booker/Tom Foley ([email protected]) WORKSHOP CHAIRPERSON Eleanor Kinzie SPECIAL PROJECTS Deb Booker/Tom Foley Senior CBS FCBS Rep. Vicky Chirnside ([email protected]) Co-Junior CBS FCBS Reps. Debbie Booker & Tom Foley Alternate CBS FCBS Rep. Dale Kammerlohr ([email protected]) OTHER COMMITTEES AUDIO/VISUAL SETUP Tom Foley ([email protected]); BobLura DOOR PRIZE Barbara Johnson ([email protected]) HOSPITALITY Mary McKenzie ([email protected]); Martha Wolfe SPECIAL HOSPITALITY Betsy Burdette ([email protected]) RAFFLE TICKETS Greeter/Membership table volunteers - Luli Westra, Dolly Dalton, Eleanor Kinzie, etc. RAFFLE COMMENTARY Larry Giroux GREETERS/ATTENDENCE Betty Ann Prevatt, Dolly Dalton([email protected]), Luli Westra SHOW & TELL Dale Kammerlohr FM-LEE GARDEN COUNCIL Mary McKenzie LIBRARIAN Sue Gordon ASSISTANT LIBRARIAN Kay Janssen The opinions expressed in the Meristem are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Editor or the official policy of CBS. -

BROMELI ANA PUBLISHED by the NEW YORK BROMELIAD SOCIETY1 (Visit Our Website

BROMELI ANA PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK BROMELIAD SOCIETY1 (visit our website www.nybromeliadsociety.org) October, 2015 Vol. 52, No. 7 MANAGING AND MAINTAINING MY PLANT COLLECTION by Cynthia Percarpio I love plants - particularly bromeliads. The dried out or died due to the lack of a simple watering challenge is that my time is very limited; I have two schedule. So I came up with a working system which little kids, some pets and a full-time job. Balancing helps keep my plants alive during the cooler months. everything in life can be tricky. I find, as I assume The plants in my garden window are on many of you share, that plants are a humidity trays which help alleviate wonderful escape - watching these the dryness. Most importantly, I specimens grow and thrive brings keep a colorful post-it note on the amazement and joy as well as a trim of the window indicating the sense of satisfaction. date that the plants were last There are a few tricks that I watered. I use the same post-it to have utilized most recently in order write on for many weeks. to improve the success rate and Surprisingly (or not) I’ve realized increase the overall vibrancy of my that I have no clue as to when I last bromeliads. Included in this article watered the plants unless I write it are maintaining a watering schedule, down! So, this list is essential. water quality, fertilization, potting, I also write down what part winter storage and record keeping. of the collection has been watered. -

Phylogeny, Adaptive Radiation, and Historical Biogeography of Bromeliaceae Inferred from Ndhf Sequence Data Thomas J

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 4 2007 Phylogeny, Adaptive Radiation, and Historical Biogeography of Bromeliaceae Inferred from ndhF Sequence Data Thomas J. Givnish University of Wisconsin, Madison Kendra C. Millam University of Wisconsin, Madison Paul E. Berry University of Wisconsin, Madison Kenneth J. Sytsma University of Wisconsin, Madison Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Givnish, Thomas J.; Millam, Kendra C.; Berry, Paul E.; and Sytsma, Kenneth J. (2007) "Phylogeny, Adaptive Radiation, and Historical Biogeography of Bromeliaceae Inferred from ndhF Sequence Data," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 23: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol23/iss1/4 Aliso 23, pp. 3–26 ᭧ 2007, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden PHYLOGENY, ADAPTIVE RADIATION, AND HISTORICAL BIOGEOGRAPHY OF BROMELIACEAE INFERRED FROM ndhF SEQUENCE DATA THOMAS J. GIVNISH,1 KENDRA C. MILLAM,PAUL E. BERRY, AND KENNETH J. SYTSMA Department of Botany, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, USA 1Corresponding author ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Cladistic analysis of ndhF sequences identifies eight major bromeliad clades arranged in ladderlike fashion. The traditional subfamilies Tillandsioideae and Bromelioideae are monophyletic, but Pitcair- nioideae are paraphyletic, requiring the description of four new subfamilies, recircumscription of Pit- cairnioideae and Navioideae, the sinking of Ayensua, and description of the new genus Sequencia. Brocchinioideae are basalmost, followed by Lindmanioideae, both restricted to the Guayana Shield. Next is an unresolved trichotomy involving Hechtioideae from Central America, Tillandsioideae, and the remaining bromeliads in subfamilies Navioideae, Pitcairnioideae, Puyoideae, and Bromelioideae. -

HUNTIA a Journal of Botanical History

HUNTIA A Journal of Botanical History VolUme 11 NUmBer 1 2000 Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie mellon University Pittsburgh Huntia publishes articles on all aspects of the his- tory of botany and is published irregularly in one or more numbers per volume of approximately 200 pages by the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213-3890. editor Scarlett T. Townsend Book reviews and Announcements editor Charlotte A. Tancin Associate editors Gavin D. r. Bridson T. D. Jacobsen Angela l. Todd Frederick H. Utech James J. White layout Lugene B. Bruno external contributions to Huntia are welcome. Please request our “Guidelines for Contributors” before submitting manuscripts for consideration. editorial correspondence should be directed to the editor. Books for announcement or review should be sent to the Book reviews and Announcements editor. Page charge is $50.00. The charges for up to five pages per year are waived for Hunt Institute Associates, who also may elect to receive Huntia as a benefit of membership; please contact the Institute for more information. Subscription rate is $60.00 per volume. orders for subscriptions and back issues should be sent to the Institute. Printed and bound by Allen Press, Inc., lawrence, Kansas. Copyright © 2000 by the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation All rights reserved ISSN 0073-4071 Huntia 11(1) 2000 Jamaican plant genera named by Patrick Browne (ca. 1720–1790): A checklist with an attempt at an etymology P. H. Oswald and E. Charles Nelson Abstract Patrick Browne’s generic names for Jamaican native them. Most meanings are taken from Liddell plants, published during 1756, are listed and their and Scott (1940) and Lewis and Short (1879). -

Nuclear Genes, Matk and the Phylogeny of the Poales

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2018 Nuclear genes, matK and the phylogeny of the Poales Hochbach, Anne ; Linder, H Peter ; Röser, Martin Abstract: Phylogenetic relationships within the monocot order Poales have been well studied, but sev- eral unrelated questions remain. These include the relationships among the basal families in the order, family delimitations within the restiid clade, and the search for nuclear single-copy gene loci to test the relationships based on chloroplast loci. To this end two nuclear loci (PhyB, Topo6) were explored both at the ordinal level, and within the Bromeliaceae and the restiid clade. First, a plastid reference tree was inferred based on matK, using 140 taxa covering all APG IV families of Poales, and analyzed using parsimony, maximum likelihood and Bayesian methods. The trees inferred from matK closely approach the published phylogeny based on whole-plastome sequencing. Of the two nuclear loci, Topo6 supported a congruent, but much less resolved phylogeny. By contrast, PhyB indicated different phylo- genetic relationships, with, inter alia, Mayacaceae and Typhaceae sister to Poaceae, and Flagellariaceae in a basally branching position within the Poales. Within the restiid clade the differences between the three markers appear less serious. The Anarthria clade is first diverging in all analyses, followed by Restionoideae, Sporadanthoideae, Centrolepidoideae and Leptocarpoideae in the matK and Topo6 data, but in the PhyB data Centrolepidoideae diverges next, followed by a paraphyletic Restionoideae with a clade consisting of the monophyletic Sporadanthoideae and Leptocarpoideae nested within them. The Bromeliaceae phylogeny obtained from Topo6 is insufficiently sampled to make reliable statements, but indicates a good starting point for further investigations. -

Network Scan Data

Selbyana 15: 1-7 HOW MUCH IS KNOWN ABOUT BROMELIACEAE IN 1994? DAVID H. BENZING Department of Biology, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio 44074 USA If access and utility alone dictated scientific no exhaustive review of the immense literature interest, much less would be known about Bro is attempted, only highlights of accomplish meliaceae today. Fully one half of all its species ments, sprinkled here and there with exhorta grow in trees, many in remote rain forests. An tions and a bit of guarded speculation. But first other sizable group of terrestrials similarly dis we need some statistics, current and projected, courages study by occurring in roadless, bleak, and then some thoughts about the magnitude of upper montane habitats (e.g., Navia, Puya, many the task and the nature of the goals. Areas of Tillandsia spp.) especially in South America. inquiry follow, each updated to reflect current Commercial promise has not provided much en status and lastly, a concluding remark. couragement for researchers either. Beyond the pineapple, some widely marketed ornamentals, SYSTEMATICS, TAXONOMY AND and a few minor fiber products, bromeliads sim EVOLUTION ply offer too little potential to merit funding any where near that invested to study the more wide Bromeliaceae is the largest, almost exclusively ly useful Poaceae, Fabaceae, Rosaceae and their American family (one African Pitcairnia sp.) of kind. Nevertheless, bromeliads have attracted flowering plants. Likewise, its basic tropical char more than their share of scholarship beginning acter and relative youth are beyond dispute. with the attentions of an impressive array of However, many additional points, including nineteenth century, comparative and functional much of its taxonomy, are more equivocal.