0 0 Tithe an Oireachtais

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999

TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased through any bookseller, or directly from the GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, SUN ALLIANCE HOUSE, MOLESWORTH STREET, DUBLIN 2 £12.00 €15.24 © Copyright Government of Ireland 2000 ISBN 0-7076-6434-9 P. 33331/E Gr. 30-01 7/00 3,000 Brunswick Press Ltd. ii CLÁR CONTENTS Page Foreword........................................................................................................................................................................ v Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... vii LOCAL AUTHORITIES County Councils Carlow...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Cavan....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Clare ........................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Cork (Northern Division) .......................................................................................................................................... 19 Cork (Southern Division)......................................................................................................................................... -

Annual Report Of

NATIONAL ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT OFFICE ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2007 National Economic and Social Development Office 1 16 Parnell Square Dublin 1 Index 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 3 2 FUTURESIRELAND PROJECT ...................................................................................... 5 3 NATIONAL ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL ................................................. 8 4 NATIONAL ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL FORUM .................................................... 14 5 NATIONAL CENTRE FOR PARTNERSHIP AND PERFORMANCE .................. 31 6 FINANCIAL STATEMENT ........................................................................................... 45 Appendix 1 – NESDO Board Membership .......................................................... 62 Appendix 2 - NESC Council Membership ....................................................... 63 Appendix 3 - NESF ......................................................................................................... 66 Appendix 4 NCPP Council Membership ............................................................ 71 National Economic and Social Development Office 2 16 Parnell Square Dublin 1 1 INTRODUCTION The National Economic and Social Development Office (NESDO) was established by the National Economic and Social Development Office Act, 2006. The functions of NESDO are to advise the Taoiseach on all strategic matters relevant to the economic and social -

Miscellaneous Notes on Republicanism and Socialism in Cork City, 1954–69

MISCELLANEOUS NOTES ON REPUBLICANISM AND SOCIALISM IN CORK CITY, 1954–69 By Jim Lane Note: What follows deals almost entirely with internal divisions within Cork republicanism and is not meant as a comprehensive outline of republican and left-wing activities in the city during the period covered. Moreover, these notes were put together following specific queries from historical researchers and, hence, the focus at times is on matters that they raised. 1954 In 1954, at the age of 16 years, I joined the following branches of the Republican Movement: Sinn Féin, the Irish Republican Army and the Cork Volunteers’Pipe Band. The most immediate influence on my joining was the discovery that fellow Corkmen were being given the opportunity of engag- ing with British Forces in an effort to drive them out of occupied Ireland. This awareness developed when three Cork IRA volunteers were arrested in the North following a failed raid on a British mil- itary barracks; their arrest and imprisonment for 10 years was not a deterrent in any way. My think- ing on armed struggle at that time was informed by much reading on the events of the Tan and Civil Wars. I had been influenced also, a few years earlier, by the campaigning of the Anti-Partition League. Once in the IRA, our initial training was a three-month republican educational course, which was given by Tomas Óg MacCurtain, son of the Lord Mayor of Cork, Tomas MacCurtain, who was murdered by British forces at his home in 1920. This course was followed by arms and explosives training. -

Dáil Éireann

DÁIL ÉIREANN Dé Máirt, 11 Nollaig, 2007 Tuesday, 11th December, 2007 RIAR NA hOIBRE ORDER PAPER 72 DÁIL ÉIREANN 947 Dé Máirt, 11 Nollaig, 2007 Tuesday, 11th December, 2007 2.30 p.m. ORD GNÓ ORDER OF BUSINESS 6. Tairiscint maidir le Comhaltaí a cheapadh ar Choiste. Motion re Appointment of Members to Committee. 2. An Bille Leasa Shóisialaigh 2007 — Ordú don Dara Céim. Social Welfare Bill 2007 — Order for Second Stage. 9. Tairiscintí Airgeadais ón Aire Airgeadais [2007] (Tairiscint 5, atógáil). Financial Motions by the Minister for Finance [2007] (Motion 5, resumed). GNÓ COMHALTAÍ PRÍOBHÁIDEACHA PRIVATE MEMBERS' BUSINESS 19. Tairiscint maidir le Sábháilteacht ar Bhóithre; An córas pointí pionóis a athchóiriú. Motion re Road Safety; Reform of penalty points system. P.T.O. 948 I dTOSACH GNÓ PHOIBLÍ AT THE COMMENCEMENT OF PUBLIC BUSINESS Billí ón Seanad : Bills from the Seanad 1. An Bille um Eitic in Oifigí Poiblí (Leasú) 2007 [Seanad] — An Dara Céim. Ethics in Public Office (Amendment) Bill 2007 [Seanad] — Second Stage. Billí a thionscnamh : Initiation of Bills Tíolactha: Presented: 2. An Bille Leasa Shóisialaigh 2007 — Ordú don Dara Céim. Social Welfare Bill 2007 — Order for Second Stage. Bille dá ngairtear Acht do leasú agus do Bill entitled an Act to amend and extend leathnú na nAchtanna Leasa Shóisialaigh the Social Welfare Acts and to amend the agus do leasú an Achta um Ranníocaí Sláinte Health Contributions Act 1979. 1979. —An tAire Gnóthaí Sóisialacha agus Teaghlaigh. 3. Bille na nDlí-Chleachtóirí (An Ghaeilge) 2007 — Ordú don Dara Céim. Legal Practitioners (Irish Language) Bill 2007 — Order for Second Stage. -

Guide to the 30 Dáil for Anti-Poverty Groups

European Anti-Poverty Network (EAPN) Ireland Guide to the 30th Dáil for Anti-Poverty Groups ‘EAPN Ireland is a network of groups and individuals working against poverty and social exclusion. Our objective is to put the fight against poverty at the top of the European and Irish agendas’ Contents Page Acknowledgements 2 Introduction 2 The Parties 4 Dáil Session Guide 5 A Brief Guide to Legislation 7 Dáil Committees 9 The TD in the Dáil 9 Contacting a TD 12 APPENDICES 1: List of Committees and Spokespersons 2: Government Ministers and Party Spokespersons 1 Introduction This Guide has been produced by the European Anti-Poverty Network (EAPN) Ireland. It is intended as a short briefing on the functioning of the Dáil and a simple explanation of specific areas that may be of interest to people operating in the community/NGO sector in attempting to make the best use of the Dáil. This briefing document is produced as a result of the EAPN Focus on Poverty in Ireland project, which started in December 2006. This project aimed to raise awareness of poverty and put poverty reduction at the top of the political agenda, while also promoting understanding and involvement in the social inclusion process among people experiencing poverty. This Guide is intended as an accompanying document to the EAPN Guide to Understanding and Engaging with the European Union. The overall aim in producing these two guides is to inform people working in the community and voluntary sector of how to engage with the Irish Parliament and the European Union in influencing policy and voicing their concerns about poverty and social inclusion issues. -

An Comhchoiste Um an Leasú Bunreachta Maidir Le Leanaí An

An Comhchoiste um an Leasú Bunreachta maidir le Leanaí An Dara Tuarascáil An Bille um an Ochtú Leasú is Fiche ar an mBunreacht 2007 An Dara Tuarascáil Eatramhach AIRTEAGAL 42(A).5.2° - Togra chun údarás dlíthiúil a thabhairt chun cionta a chruthú ar cionta dliteanais iomláin nó diandliteanais i leith cionta gnéasacha in aghaidh leanaí nó i dtaca le leanaí iad Bealtaine 2009 Joint Committee on the Constitutional Amendment on Children Second Report Twenty-eighth Amendment of the Constitution Bill 2007 Second Interim Report O ARTICLE 42(A).5.2 - Proposal to give legal authority to create offences of absolute or strict liability in respect of sexual offences against or in connection with children May 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chairperson’s Foreword 3 The Committee’s Recommendations 5 Introduction 14 1. Establishment and Terms of Reference 14 2. The Work of the Committee 15 The Defence of Mistake and the Constitution 17 3. The Question of Terminology 17 4. The Constitutional and Human Rights Context 18 5. A Review of Developments to Date 25 6. The Desirability of Constitutional Amendment 28 7. The Text of the Proposed Amendment 42 8. Alternative to Amendment – Legislation and Early Challenge 46 The Scope for Legislative Amendment 48 9. The Mental Element 48 10. The Onus and Standard of Proof 51 11. Criminal Procedure 53 Age of Consent and Peer Sexual Relations 59 12. Fixing the Age of Consent 59 13. The Problem of Peer Relations and the Role of the Prosecution 61 1 APPENDIX A: Orders of Reference of the Committee 66 APPENDIX B: Submissions to the Committee 70 APPENDIX C: Committee Hearings and Briefings 75 APPENDIX D: Committee Membership 79 APPENDIX E: Twenty-eighth Amendment of the Constitution Bill 2007 83 2 CHAIRPERSON’S FOREWORD On behalf of the Joint Committee on the Constitutional Amendment on Children, I am pleased to present this Second Interim Report on the Twenty-eighth Amendment of the Constitution Bill 2007 to the Houses of the Oireachtas for consideration and debate. -

Da´Il E´Ireann

Vol. 639 Wednesday, No. 2 10 October 2007 DI´OSPO´ IREACHTAI´ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DA´ IL E´ IREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIU´ IL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Wednesday, 10 October 2007. Leaders’ Questions ……………………………… 437 Ceisteanna—Questions Taoiseach ………………………………… 445 Death of Former Member: Expressions of Sympathy ………………… 476 Requests to move Adjournment of Da´il under Standing Order 32 ……………… 481 Order of Business ……………………………… 482 Charities Bill 2007: Order for Second Stage …………………………… 492 Second Stage ……………………………… 492 Ceisteanna—Questions (resumed) Minister for the Environment, Heritage and Local Government Priority Questions …………………………… 508 Other Questions …………………………… 518 Visit of Northern Ireland Delegation ………………………… 524 Ceisteanna—Questions (resumed) Minister for the Environment, Heritage and Local Government …………… 524 Adjournment Debate Matters …………………………… 536 Charities Bill 2007: Second Stage (resumed) ……………………… 536 Private Members’ Business Fire Services: Motion (resumed) ………………………… 587 Adjournment Debate Hospital Services ……………………………… 621 Pig Industry ……………………………… 624 Road Traffic Offences …………………………… 628 Fire Services ……………………………… 630 Questions: Written Answers …………………………… 633 437 438 DA´ IL E´ IREANN was a commercial decision on the part of Aer Lingus and the company has reiterated that it will ———— not change that decision. The Government is con- scious that this will create difficulties for the De´ Ce´adaoin, 10 Deireadh Fo´mhair 2007. region and several members have met all the rel- Wednesday, 10 October 2007. evant organisations from Shannon. ———— Deputy Pa´draic McCormack: It has done nothing. Chuaigh an Ceann Comhairle i gceannas ar 10.30 a.m. The Taoiseach: Several of my colleagues have gone to the region and I have met several of those ———— organisations. I met all the main organisations who sought meetings with me in the middle of Paidir. -

Potential Outcomes for the 2007 and 2011 Irish Elections Under a Different Electoral System

Publicpolicy.ie Potential Outcomes for the 2007 and 2011 Irish elections under a different electoral system. A Submission to the Convention on the Constitution. Dr Adrian Kavanagh & Noel Whelan 1 Forward Publicpolicy.ie is an independent body that seeks to make it as easy as possible for interested citizens to understand the choices involved in addressing public policy issues and their implications. Our purpose is to carry out independent research to inform public policy choices, to communicate the results of that research effectively and to stimulate constructive discussion among policy makers, civil society and the general public. In that context we asked Dr Adrian Kavanagh and Noel Whelan to undertake this study of the possible outcomes of the 2007 and 2011 Irish Dail elections if those elections had been run under a different electoral system. We are conscious that this study is being published at a time of much media and academic comment about the need for political reform in Ireland and in particular for reform of the electoral system. While this debate is not new, it has developed a greater intensity in the recent years of political and economic volatility and in a context where many assess the weaknesses in our political system and our electoral system in particular as having contributed to our current crisis. Our wish is that this study will bring an important additional dimension to discussion of our electoral system and of potential alternatives. We hope it will enable members of the Convention on the Constitution and those participating in the wider debate to have a clearer picture of the potential impact which various systems might have on the shape of the Irish party system, the proportionality of representation, the stability of governments and the scale of swings between elections. -

Seanad General Election July 2002 and Bye-Election to 1997-2002

SEANAD E´ IREANN OLLTOGHCHA´ N DON SEANAD, IU´ IL 2002 agus Corrthoghcha´in do Sheanad 1997-2002 SEANAD GENERAL ELECTION, JULY 2002 and Bye-Elections to 1997-2002 Seanad Government of Ireland 2003 CLA´ R CONTENTS Page Seanad General Election — Explanatory Notes ………………… 4 Seanad General Election, 2002 Statistical Summary— Panel Elections …………………………… 8 University Constituencies ………………………… 8 Panel Elections Cultural and Educational Panel ……………………… 9 Agricultural Panel …………………………… 13 Labour Panel ……………………………… 19 Industrial and Commercial Panel ……………………… 24 Administrative Panel …………………………… 31 University Constituencies National University of Ireland………………………… 35 University of Dublin …………………………… 37 Statistical Data — Distribution of Seats between the Sub-Panels 1973-02 … … … 38 Members nominated by the Taoiseach …………………… 39 Alphabetical list of Members ………………………… 40 Photographs Photographs of candidates elected ……………………… 42 Register of Nominating Bodies, 2002 ……………………… 46 Panels of Candidates …………………………… 50 Rules for the Counting of Votes Panel Elections ……………………………… 64 University Constituencies ………………………… 68 Bye-Elections ……………………………… 71 23 June, 1998 ……………………………… 72 2 June, 2000 ……………………………… 72 2 June, 2002 ……………………………… 73 18 December, 2001 …………………………… 73 3 SEANAD GENERAL ELECTION—EXPLANATORY NOTES A. CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS ARTICLE 18 ‘‘4. The elected members of Seanad E´ ireann shall be elected as follows:— i. Three shall be elected by the National University of Ireland. ii. Three shall be elected by the University of Dublin. iii. Forty-three shall be elected from panels of candidates constituted as hereinafter provided. 5. Every election of the elected members of Seanad E´ ireann shall be held on the system of proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote, and by secret postal ballot. 6. The members of Seanad E´ ireann to be elected by the Universities shall be elected on a franchise and in the manner to be provided by law. -

Dáil Éireann

DÁIL ÉIREANN Dé Máirt, 4 Samhain, 2008 Tuesday, 4th November, 2008 RIAR NA hOIBRE ORDER PAPER 76 DÁIL ÉIREANN 1173 Dé Máirt, 4 Samhain, 2008 Tuesday, 4th November, 2008 2.30 p.m. ORD GNÓ ORDER OF BUSINESS 10. Tairiscint maidir le Róta na nAirí i gcomhair Ceisteanna Parlaiminte. Motion re Ministerial Rota for Parliamentary Questions. 2. An Bille um Chnuas-Mhuinisin agus Mianaigh Fhrithphearsanra 2008 — Ordú don Dara Céim. Cluster Munitions and Anti-Personnel Mines Bill 2008 — Order for Second Stage. 16. Tairiscintí Airgeadais ón Aire Airgeadais [2008] (Tairiscint 15, atógáil). Financial Motions by the Minister for Finance [2008] (Motion 15, resumed). GNÓ COMHALTAÍ PRÍOBHÁIDEACHA PRIVATE MEMBERS' BUSINESS 44. Tairiscint maidir le Cláir Oiliúna. Motion re Training Programmes. P.T.O. 1174 I dTOSACH GNÓ PHOIBLÍ AT THE COMMENCEMENT OF PUBLIC BUSINESS Billí ón Seanad : Bills from the Seanad 1. An Bille um Eitic in Oifigí Poiblí (Leasú) 2007 [Seanad] — An Dara Céim. Ethics in Public Office (Amendment) Bill 2007 [Seanad] — Second Stage. Billí a thionscnamh : Initiation of Bills Tíolactha: Presented: 2. An Bille um Chnuas-Mhuinisin agus Mianaigh Fhrithphearsanra 2008 — Ordú don Dara Céim. Cluster Munitions and Anti-Personnel Mines Bill 2008 — Order for Second Stage. Bille dá ngairtear Acht do thabhairt Bill entitled an Act to give effect to the éifeacht don Choinbhinsiún ar Chnuas- Convention on Cluster Munitions, done at Mhuinisin, a rinneadh i mBaile Átha Cliath Dublin on 30 May 2008, and to give further an 30 Bealtaine 2008, agus do thabhairt effect to the Convention on the Prohibition tuilleadh éifeachta don Choinbhinsiún of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and maidir le Toirmeasc ar Úsáid, Stoc- Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Charnadh, Táirgeadh agus Aistriú Mianach their Destruction, done at Oslo on 18 Frithphearsanra agus maidir lena nDíothú, a September 1997, and to provide for related rinneadh in Osló an 18 Meán Fómhair 1997, matters. -

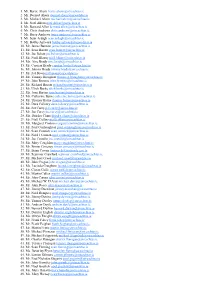

1. Mr. Bertie Ahern [email protected] 2. Mr. Dermot Ahern [email protected] 3. Mr. Michael Ahern [email protected] 4

1. Mr. Bertie Ahern [email protected] 2. Mr. Dermot Ahern [email protected] 3. Mr. Michael Ahern [email protected] 4. Mr. Noel Ahern [email protected] 5. Mr. Bernard Allen [email protected] 6. Mr. Chris Andrews [email protected] 7. Mr. Barry Andrews [email protected] 8. Mr. Seán Ardagh [email protected] 9. Mr. Bobby Aylward [email protected] 10. Mr. James Bannon [email protected] 11. Mr. Sean Barrett [email protected] 12. Mr. Joe Behan [email protected] 13. Mr. Niall Blaney [email protected] 14. Ms. Aíne Brady [email protected] 15. Mr. Cyprian Brady [email protected] 16. Mr. Johnny Brady [email protected] 17. Mr. Pat Breen [email protected] 18. Mr. Tommy Broughan [email protected] 19. Mr. John Browne [email protected] 20. Mr. Richard Bruton [email protected] 21. Mr. Ulick Burke [email protected] 22. Ms. Joan Burton [email protected] 23. Ms. Catherine Byrne [email protected] 24. Mr. Thomas Byrne [email protected] 25. Mr. Dara Calleary [email protected] 26. Mr. Pat Carey [email protected] 27. Mr. Joe Carey [email protected] 28. Ms. Deirdre Clune [email protected] 29. Mr. Niall Collins [email protected] 30. Ms. Margaret Conlon [email protected] 31. Mr. Paul Connaughton [email protected] 32. Mr. Sean Connick [email protected] 33. Mr. Noel J Coonan [email protected] 34. -

¥ Labour Shortages.Pp 2

CONOM L E IC A A N N IO D T A S O N C I E A H L T FORUM Fóram Náisiúnta Eacnamaioch agus Sóisialach Alleviating Labour Shortages Forum Report No. 19 November 2000 PUBLISHED BY THE NATIONAL ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL FORUM Copies of this Report may be obtained from the: GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALES OFFICE Sun Alliance House, Molesworth Street, Dublin 2. or THE NATIONAL ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL FORUM Frederick House, 19 South Frederick Street, Dublin 2. Price: IR£5.00 e6.35 (PN 9208) ISBN 1-899276-23-8 Contents Page Foreword 5 Section I Introduction and Overview 9 Section II Labour Market Assessment 23 Section III Employment and Non-Employment 39 Section IV The Participation Challenge 51 Section V A Comprehensive Welfare to Work Strategy 65 Section VI Individual orJoint Taxation? 79 Section VII Women Returning to the Labour Market 93 Section VIII Immigration Policy 103 Annex I References 119 Annex II Project TeamÕs Terms of Reference 119 Terms of Reference and Constitution of the Forum 123 Membership of the Forum 124 Forum Publications 126 3 Foreword Since 1994, Ireland has experienced an unprecedented growth in employment and as a corollary, a dramatic fall in unemployment. This success has, however, brought new labour market challenges as labour and skill shortages and associated recruitment difficulties have emerged across the economy. It is against this background that, in December of last year, the Forum established a Project Team to prepare a Report on Labour Shortages. A draft of this Report was considered by the Forum at its Plenary Session in Dublin on October 10th last.