Freedom on the Net 2017 India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investor Presentation – July 2017

Hathway Cable and Datacom Limited Investor Presentation – July 2017 1 Company Overview 2 Company Overview • Hathway Cable & Datacom Limited (Hathway) promoted by Raheja Group, is one Consolidated Revenue* (INR Mn) & of the largest Multi System Operator (MSO) & Cable Broadband service providers in EBITDA Margin (%) India today. 14,000 16.2% 20.0% 13,000 15.0% • The company’s vision is to be a single point access provider, bringing into the home and work place a converged world of information, entertainment and services. 12,000 12.1% 13,682 10.0% 11,000 11,550 5.0% • Hathway is listed on both the BSE and NSE exchanges and has a current market 10,000 0.0% th capitalisation of approximately INR 28 Bn as on 30 June, 2017. FY16 FY17 Broadband Cable Television FY17 Operational - Revenue Break-up • Hathway holds a PAN India ISP license • One of India’s largest Multi System Activation Other and is the first cable television services Operator (MSO), across various regions 6% 2% Cable Subscription provider to offer broadband Internet of the country and transmitting the 34% services same to LCOs or directly to subscribers. • Approximately 4.4 Mn two-way • Extensive network connecting 7.5 Mn Placement broadband homes passed CATV households and 7.2 Mn digital 21% cable subscriber • Total broadband Subscribers – 0.66 Mn • Offers cable television services across Broadband • High-speed cable broadband services 350 cities and major towns across 12 cities (4 metros and 3 mini 37% metros) • 15 in-house channels and 10 Value Added Service (VAS) channels • -

LIST of ISP LICENSEES AS on 30.06.2015* Sl No Name of Company CAT Service Area

LIST OF ISP LICENSEES AS ON 30.06.2015* Sl No Name of Company CAT Service Area 1 Reliance Communications Infrastructure Ltd. A All India 2 Dishnet Wireless Ltd. A All India 3 Tata Communications Limited A All India 4 RPG Infotech Ltd. A All India 5 Value Healthcare Ltd B Mumbai 6 Hughes Communications India Limited A All India 7 Karuturi Telecom Private Limited A All India 8 Micky Online Pvt. Ltd. C Moradabad 9 Seven Star Dot Com Private Limited B Mumbai 10 Gujarat Narmada Valley Fertilizers Company Ltd. A All India 11 Kerala Communication Network Pvt. Ltd. B Kerala 12 North East Online Services Pvt. Ltd. C Guwahati 13 The Tata Power Company Ltd A All India 14 Asianet Satellite Communications Ltd. B Kerala 15 M/s Reliance Ports and Terminals Limited [Earlier M/s Reliance Engineering A All India Associates Pvt. Ltd.] 16 Hathway Bhawani Cabeltel & Datacom Ltd. B Mumbai 17 Millennium Telecom. Ltd. A All India 18 Amber Online Services Ltd. B Andhra Pradesh 19 Tata Teleservices Ltd. A All India 20 Web Cable TV Ltd C Nagercoil 21 Netkracker Ltd. A All India 22 Karuturi Global Limited B Karnataka 23 SAB Infotech Ltd. C Dharamshala 24 SAB Infotech Ltd. C Karnal 25 Sujan Engineering Pvt. Ltd. C Vadodara 26 Space Online Ltd. B Gujarat 27 World Phone Internet Services Pvt. Ltd. A All India 28 C-DAC, Noida C Ghaziabad 29 Essel Shyam Communications Ltd. A All India 30 Forum Infotech Pvt. Ltd. C Srinagar 31 Micky Online Pvt. Ltd. C Nainintal 32 Reach Network India Pvt. -

Achievement-2011.Pdf

UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF LEGAL STUDIES Publications Books Dr. Navneet Arora, Youth and New Media ( 2011) by Unistar Publications: Chandigarh. ISBN-978-93-5017-660-3 Dr. Jasmeet Gulati ‘International Criminal Law- Development, Evolution and Genesis’, Lambert Academic Publishing GmbH & Co. (2011 Ed.) ISBN 978-3-8465-4808-0 (Nov. 30, 2011) Research papers in referred journals Dr. Sasha • “The Colonial Response to the Plague in the Punjab 1897- 1947 ”, in Punjab Journal of Sikh Studies, Volume I, 2011, Department of Guru Nanak Sikh Studies, Panjab University, Chandigarh. ISSN No.:2231-2757 Dr. Chanchal Narang • “Environment and the Creativity of a Literary Artist” in Journal of University Institute of Legal Studies, Vol. III, 2009,Pg.48-58. ISSN No. 2229-3906 • “Involving Learners in the Learning Process” – A Study with Reference to the Students of Law In The Literati ,Vol. I Issue 1 June 2011. Pg 117-128 ISSN No. 2248-9576 • “Understanding Culture to Teach Language” in The Dialogue No. 22(Spring 2012) pg. 73-88. ISSN No. 0975-4881 Dr. Pushpinder Kaur • “Development and Environment: Global and Indian Perspectives” in Punjab Journal of Politics, Vol.35, Nos. 1-2, 2011, pg 17-34 , ISSN No. 0253-3960 Dr. Shruti Bedi • “Watching the Watchmen” in the Supreme Court Cases (2011)5SCC • “The legal Lacunas of an Indian Corporation’s Criminal Liability” in The International Journal of Research in Commerce, IT and Management(a double blind peer reviewed, refereed e- journal available at www.ijrcm.org.in,Vol.1(2011),IssueNo.5(October)p149 ISSN no. 2231-5756) • “Sacrificing Human Rights at the Altar of Terrorism” in the Panjab University Law Review, 51PULR(2010)134.,2011). -

UL-ISP Licences Final March 2015.Xlsx

Unified License of ISP Authorization S. No. Name of Licensee Cate Service Authorized person Registered Office Address Contact No. LanLine gory area 1 Mukand Infotel Pvt. Ltd. B Assam Rishi Gupta AC Dutta Lane , FA Road 0361-2450310 fax: no. Kumarpara, Guwahati- 781001, 03612464847 Asaam 2 Edge Telecommunications B Delhi Ajay Jain 1/9875, Gali No. 1, West Gorakh 011-45719242 Pvt. Ltd. Park, Shahdara, Delhi – 110032 3 Southern Online Bio B Andhra Satish kumar Nanubala A3, 3rd Floor, Office Block, Samrat 040-23241999 Technologies Ltd Pradesh Complex, Saifabad, Hyderabad-500 004 4 Blaze Net Limited B Gujarat and Sharad Varia 20, Paraskunj Society, Part I, Nr. 079-26405996/97,Fax- Mumbai Umiyavijay, Satellite Road, 07926405998 Ahmedabad-380015 Gujarat 5 Unified Voice Communication B + Tamilnadu K.Rajubharathan Old No. 14 (New No. 35), 4th Main 044-45585353 Pvt. Ltd. C (including Road, CIT Nagar, Nanthanam, Chennai)+ Chennai – 600035 Bangalore 6 Synchrist Network Services Pvt. B Mumbai Mr. Kiran Kumar Katara Shop No. 5, New Lake Palace Co- 022-61488888 Ltd , Director op-Hsg. Ltd., Plot No. 7-B, Opp Adishankaracharya Road, Powai, Mumbai – 400076 (MH) 7 Vala Infotech Pvt. Ltd. B Gujarat Mr. Bharat R Vala, Dhanlaxmi Building, Room No. 309, (02637) 243752. Fax M.D. 3rd Floor, Near Central Bank, (02637) 254191 Navsari – 396445 Gujarat 8 Arjun Telecom Pvt. C Chengalpatt Mr. N.Kannapaan, New No. 1, Old No. 4, 1st Floor, 044-43806716 Ltd(cancelled) u Managing Direcot, Kamakodi Nagar, Valasaravakkam, (Kancheepu Chennai – 600087 ram) 9 CNS Infotel Services Pvt. Ltd. B Jammu & Reyaz Ahmed Mir M.A. -

Copy of TP-Concession to Customers R Final 22.04.2021.Xlsx

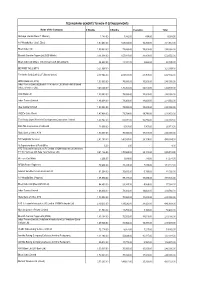

TECHNOPARK-BENEFITS TO NON-IT ESTABLISHMENTS Name of the Company 6 Months 3 Months Esclation Total Akshaya (Kerala State IT Mission) 1,183.00 7,332.00 488.00 9,003.00 A V Hospitalities ( Café Elisa) 1,97,463.00 1,08,024.00 16,200.00 3,21,687.00 Bharti Airtel Ltd 1,50,000.00 75,000.00 15,000.00 2,40,000.00 Bharath Sanchar Nigam Ltd (BSS Mobile) 3,14,094.00 1,57,047.00 31,409.00 5,02,550.00 Bharti Airtel Ltd (Bharti Tele-Ventures Ltd (Broad band) 26,622.00 13,311.00 2,662.00 42,595.00 BEYOND THE LIMITS 3,21,097.00 - - 3,21,097.00 Fire In the Belly Café L.L.P (Buraq Space) 4,17,066.00 2,08,533.00 41,707.00 6,67,306.00 HDFC Bank Ltd (ATM) 1,50,000.00 75,000.00 15,000.00 2,40,000.00 Indus Towers Limited [Bharti Tele-Ventures Ltd (Mobile-Airtel) Bharti Infratel Ventures Ltd] 3,40,524.00 1,70,262.00 34,052.00 5,44,838.00 ICICI Bank Ltd 1,50,000.00 75,000.00 15,000.00 2,40,000.00 Indus Towers Limited 1,46,604.00 73,302.00 14,660.00 2,34,566.00 Idea Cellular Limited 1,50,000.00 75,000.00 15,000.00 2,40,000.00 JODE's Cake World 1,47,408.00 73,704.00 14,741.00 2,35,853.00 The Kerala State Women's Development Corporation Limited 1,67,742.00 83,871.00 16,774.00 2,68,387.00 RAILTEL Corporation of India Ltd 13,008.00 6,504.00 1,301.00 20,813.00 State Bank of India, ATM 1,50,000.00 75,000.00 15,000.00 2,40,000.00 SS Hospitality Services 2,81,190.00 1,40,595.00 28,119.00 4,49,904.00 Sr.Superintendent of Post Office 6.00 3.00 - 9.00 ATC Telecom Infrastructure (P) Limited (VIOM Networks Ltd (Wireless TT Info Services Ltd, Tata Tele Services Ltd) 3,41,136.00 -

A Report on Pilot Social Audit of Mid Day Meal Programme May, 2015

A Report on Pilot Social Audit of Mid Day Meal Programme May, 2015 Submitted to: Secretary, School and Mass Education Department, Odisha Prepared by: Lokadrusti, At- Gadramunda, Po- Chindaguda, Via- Khariar, Dist.- Nuapada (Odisha) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Lokadrusti has been assigned the project of “Pilot Social Audit of Mid Day Meal Programme in Nuapada district” by State Project Management Unit (MDM), School and Mass Education Department, Government of Odisha. I am thankful to Secretary, School and Mass Education Department, Government of Odisha, for providing an opportunity to undertake this activity of social audit of MDM. I acknowledge the support extended by the Director and state project management unit of MDM, Odisha from time to time. I am thankful to the District Education Officer, District Project Coordinator of Sarva Sikhya Abhiyan, Nuapada and Block Education Officer of Boden and Khariar block for their support and cooperation. My heartfelt thanks to all the social audit resource persons, village volunteers, School Management Committee members, parents, students, cooks, Panchayatiraj representatives and Women Self Help Group members those helped in conducting the field visit, data collection, focused group discussions and village level meetings. I express all the headmasters and teachers in the visited schools for providing us with relevant information. I am extremely thankful to the Lokadrusti team members to carry this project of social relevance and document the facts for public vigilance and to highlight the grass root level problems of MDM scheme to plan further necessary interventions. Abanimohan Panigrahi Member Secretary, Lokadrusti [i] Preface Primary school children (6-14 years) form about 20 per cent of the total population in India. -

Audit Bureau of Circulations

Audit Bureau Of Circulations Founder Member : International Federation of Audit Bureaux of Circulations Wakefield House, Sprott Road, Ballard Estate, Mumbai – 400 001 Tel: +91 22 2261 18 12 / 2261 90 72 . Fax: +91 22 2261 88 21 E-mail :[email protected] Web Site : http://www.auditbureau.org 21st October, 2016 To, All Members Notification No. 846 PART I: AMENDMENT TO BUREAU’S CODE FOR PUBLICITY – DISCLAIMER FOR VARIANT COPIES To be added under para 2(a)(ii) under the heading “Definitions/scope” 2. a) DISCLAIMER A disclaimer in the same font and size as the main claim is required to be mentioned whenever variant copies are included in the total copies for any claim, publicity, ranking, advertisement, hoardings etc. or any other form of publicity. (main claim would be considered as one which projects – leading, highest, number one, rankings etc. and / or a claim with the largest font size) For example: If total copies of average 1,00,000 includes average 10,000 variant copies, (details of which are available on the ABC certificate of circulation) then it is necessary to mention that “the total circulation of average 1,00,000 copies includes average 10,000 variant copies” in the same font and size as of the main claim. Publisher members however can claim / publicise based on their total certified circulation figures including variant copies. This disclaimer would apply in all cases including comparison made for State, District or Town based on Area Distribution Statement certified by ABC and available to all members. This provision for a disclaimer clause was earlier intimated to all publisher members as well as discussed in detail with all publisher members in August 2016. -

Paninian Studies

The University of Michigan Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies MICHIGAN PAPERS ON SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA Ann Arbor, Michigan STUDIES Professor S. D. Joshi Felicitation Volume edited by Madhav M. Deshpande Saroja Bhate CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Number 37 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Library of Congress catalog card number: 90-86276 ISBN: 0-89148-064-1 (cloth) ISBN: 0-89148-065-X (paper) Copyright © 1991 Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89148-064-8 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-89148-065-5 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12773-3 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90169-2 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ CONTENTS Preface vii Madhav M. Deshpande Interpreting Vakyapadiya 2.486 Historically (Part 3) 1 Ashok Aklujkar Vimsati Padani . Trimsat . Catvarimsat 49 Pandit V. B. Bhagwat Vyanjana as Reflected in the Formal Structure 55 of Language Saroja Bhate On Pasya Mrgo Dhavati 65 Gopikamohan Bhattacharya Panini and the Veda Reconsidered 75 Johannes Bronkhorst On Panini, Sakalya, Vedic Dialects and Vedic 123 Exegetical Traditions George Cardona The Syntactic Role of Adhi- in the Paninian 135 Karaka-System Achyutananda Dash Panini 7.2.15 (Yasya Vibhasa): A Reconsideration 161 Madhav M. Deshpande On Identifying the Conceptual Restructuring of 177 Passive as Ergative in Indo-Aryan Peter Edwin Hook A Note on Panini 3.1.26, Varttika 8 201 Daniel H. -

Page7.Qxd (Page 1)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU WEDNESDAY, APRIL 23, 2014 (PAGE 7) Coalgate probe: CBI summons Modi will be best PM in Cong releases video clips former Coal Secretary NEW DELHI, Apr 22: India's history: Raman Singh of alleged hate speeches NEW DELHI, Apr 22: very core of the country," munal division and are openly CBI today summoned former Coal Secretary P C Parakh for NEW DELHI, Apr 22: the Lok Sabha polls. Surjewala said, adding that the trading in the politics of poison questioning on April 25 in connection with a case for alleged abuse "Modi will be the best Prime Stepping up its campaign Rejecting criticism that BJP's Prime Ministerial candi- as a weapon of last resort to gar- of official position in granting a coal block in Odisha to Hindalco, Minister in the history of India. against Narendra Modi, there was infighting within BJP, date was on the same dais with ner votes," he said in a written a company of Aditya Birla Group. Under his leadership, India will Congress today released video Chhattisgarh Chief Minister Kadam and was seen "relishing" statement. 69-year-old Parakh, who has been critical of CBI's action espe- not only realize its true potential clips of alleged "hate speeches" Raman Singh says that there the Shiv Sena leader's speech Surjewala said that this poli- cially its Director Ranjit Sinha for registering a case against him, but also get back the pride of of several BJP, Sangh Parivar was no friction among the lead- and "applauding" him by clap- tics of spreading "divisive com- has now been asked to appear before the agency on Friday during place amongst comity of and Shiv Sena leaders and ers and asserted that Narendra ping. -

Bharat Broadband Network Limited

BHARAT BROADBAND NETWORK LIMITED CITIZEN CHARTER The main objective of this exercise to issue the Citizen's Charter of Bharat Broadband network Limited (BBNL) is to improve the quality of public services. This is done by letting people know the mandate of the concerned Organization, how they can get in touch with its officials, what to expect by way of services and how to seek a remedy if something goes wrong. The Citizen's Charter does not by itself create new legal rights, but it surely helps in enforcing existing rights. Thorough care has been taken while preparing this charter, yet in case of any repugnancy inter-se the Citizen’s Charter and the Rules / Regulations or Policy Documents of BBNL, the latter shall prevail. 1. ABOUT BBNL Bharat Broadband Network Limited (BBNL), is a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), set up by the Government of India for the Establishment, Management and Operation of NOFN. BBNL has been incorporated as a Public Sector Undertaking (PSU) Company under Companies Act(1956). on 25/02/2012 Government of India has approved on 25-10-2011 the setting up of National Optical Fiber Network (NOFN) to provide connectivity to all the 2,50,000 Gram Panchayats(GPs) in the country. This would ensure broadband connectivity with adequate bandwidth. This is to be achieved utilizing the existing optical fiber and extending it to the Gram Panchayats. NOFN has the potential to transform many aspects of our lives including video, data, internet, telephone services in areas such as education, business, entertainment, environment, health households and e-governance services. -

Conference Booklet

MINISTRY OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS Government of India Conference Booklet 2017 4-5 July 2017 u New Delhi CHARTING THE COURSE FOR INDIA-ASEAN RELATIONS FOR THE NEXT 25 YEARS 2017 Contents Message by Smt. Sushma Swaraj, Minister of External Affairs, India 3 Message by Smt. Preeti Saran, Secretary (East), Ministry of External Affairs, India 5 Message by Dr A. Didar Singh, General Secretary, FICCI 7 Message by Mr Sunjoy Joshi, Director, Observer Research Foundation 9 Introduction to the Delhi Dialogue 2017 12 Concept Note 17 Key Debates 24 Agenda for 2017 Delhi Dialogue 29 Speakers: Ministerial Session 39 Speakers: Business & Academic Sessions 51 Minister of External Affairs विदेश मं配셀 India भारत सुषमा स्वराज Sushma Swaraj Message am happy that the 9th edition of the Delhi Dialogue is being jointly hosted by the Ministry of External Affairs, Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry and the Observer Research Foundation from July 4-5, 2017. On behalf Iof the Government of India, I extend a very warm welcome to all the participants. This year India and ASEAN celebrate 25 years of their Dialogue Partnership, 15 years of Summit Level interaction and 5 years of Strategic Partnership. Honouring the long standing friendship, the theme for this year’s Dialogue is aptly titled ‘Chart- ing the Course for India-ASEAN Relations for the Next 25 Years.’ At a time when the world is experiencing a number of complex challenges and transitions, consolidating and institutionalising old friendships is key to the growth and stability of our region. I am confident the different panels of the Delhi Dialogue will discuss the various dimensions of the theme and throw new light into the possible ways for India and ASEAN to move forward on common traditional and non-traditional challenges. -

Alternative Report

Alternative Report On the implementation Optional Protocol to the CRC on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography in INDIA Report prepared and submitted by: ECPAT International In collaboration with SANLAAP July 2013 1 Background information ECPAT International (End Child Prostitution, Child Pornography and Trafficking of Children for Sexual Purposes) is the leading global network working to end the commercial sexual exploitation of children (child prostitution, child pornography, child trafficking and child sex tourism). It represents 81 member organisations from 74 countries. ECPAT International holds Consultative status with ECOSOC. Website: www.ecpat.net SANLAAP literally means “dialogue” work to end child prostitution, trafficking and sexual abuse of children. Sanlaap collaborates with different stakeholders, both governmental and non- governmental to end trafficking and punish traffickers. SANLAAP operates from Kolkata and Delhi but networks with civil society organisations, police and governments all over India. Website: http://www.sanlaapindia.org/ 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction p.4 2. General measures of implementation p.5 3. Prevention of commercial sexual exploitation of children p.6 4. Prohibition of the manifestations of commercial sexual exploitation p.10 of children 5. Protection of the rights of child victims p.13 3 1. Introduction Despite a lack of research and data on the scale of commercial sexual exploitation of children in India, estimates show that many children are victims of sexual violence. UNICEF estimates that 1.2 million children are victims of prostitution in India1. The government of India has recently made significant progress in the development of laws and policies to address the different manifestations of commercial sexual exploitation of children, including the adoption in April 2013 of the National Policy for Children, which contains specific measures to prevent and combat commercial sexual exploitation of children.