Give Locally, Achieve Nationally

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2006 Ballot Measure Overview

2006 BALLOT MEASURE OVERVIEW AN A NALYSIS O F TH E MON EY RAISED A RO UND MEASU RES O N STA TE BA LLO TS I N 2006 By THE N ATIO NA L IN STI TU TE O N MON EY IN STA TE PO LI TI CS NOVEMBER 5, 2007 833 NORTH LAST CHANCE GULCH, SECOND FLOOR • HELENA, MT • 59601 PHONE 406-449-2480 • FAX 406-457-2091 • E-MAIL [email protected] www.followthemoney.org The National Institute on Money in State Politics is the only nonpartisan, nonprofit organization revealing the influence of campaign money on state-level elections and public policy in all 50 states. Our comprehensive and verifiable campaign-finance database and relevant issue analyses are available for free through our Web site FollowTheMoney.org. We encourage transparency and promote independent investigation of state-level campaign contributions by journalists, academic researchers, public-interest groups, government agencies, policymakers, students and the public at large. 833 North Last Chance Gulch, Second Floor • Helena, MT 59601 Phone: 406-449-2480 • Fax: 406-457-2091 E-mail: [email protected] www.FollowTheMoney.org This publication was made possible by grants from: JEHT Foundation, Fair and Participatory Elections Carnegie Corporation of New York, Strengthening U.S. Democracy Ford Foundation, Program on Governance and Civil Society The Pew Charitable Trusts, State Policy Initiatives Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Program on Democratic Practice The statements made and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the Institute. National Institute on Money in State Politics -

Arcus Foundation 2012 Annual Report the Arcus Foundation Is a Leading Global Foundation Advancing Pressing Social Justice and Conservation Issues

ConservationSocialJustice Arcus Foundation 2012 Annual Report The Arcus Foundation is a leading global foundation advancing pressing social justice and conservation issues. The creation of a more just and humane world, based on diversity, Arcus works to advance LGBT equality, as well as to conserve and protect the great apes. equality, and fundamental respect. L etter from Jon Stryker 02 L etter from Kevin Jennings 03 New York, U.S. Cambridge, U.K. Great Apes 04 44 West 28th Street, 17th Floor Wellington House, East Road New York, NY 10001 U.S. Cambridge CB1 1BH, U.K. Great Apes–Grantees 22 Phone +1.212.488.3000 Phone +44.1223.451050 Fax + 1. 212.488.3010 Fax +44.1223.451100 Strategy 24 [email protected] [email protected] F inancials / Board & Staff ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: © Emerson, Wajdowicz Studios / NYC / www.DesignEWS.com EDITORIAL TEAM: Editor, Sebastian Naidoo Writers, Barbara Kancelbaum & Susanne Morrell 25 THANK YOU TO OUR GRANTEES, PARTNERS, AND FRIENDS WHO CONTRIBUTED TO THE CONTENT OF THIS REPORT. © 2013 Arcus Foundation Front cover photo © Jurek Wajdowicz, Inside front cover photo © Isla Davidson Movements—whether social justice, animal conservation, or any other—take time and a sustained sense of urgency, In 2012 alone, we partnered with commitment, and fortitude. more than 110 courageous organizations hotos © Jurek Wajdowicz hotos © Jurek P working in over 40 countries around the globe. Dear Friends, Dear Friends, As I write this letter we are approaching the number 880, which represents a nearly 400 Looking back on some of the significant of the Congo. Continued habitat loss, spillover 50th anniversary of Dr. -

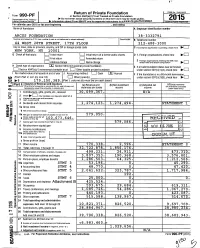

Return of Private Foundation

iN Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545.0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947( aXl) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter social security numbers on this form it may made public. Department of the Treasury ► as be 2015 internal Revenue Service lb, Information about Form 990-PF and its se parate instructions is at WwW.frS.gOV/fonn990pf. Open to im For calendar year 2015 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer Identification number ARCUS FOUNDATION 38-3332791 Number and street (or P 0 box number it marl is not delivered to street address) Room/sulte I B Telephone number 44 WEST 28TH STREET, 17TH FLOOR 212-488-3000 City or town, state or province, C if application country, and ZIP or foreign postal code exemption is pending , check here ► NEW YORK, NY 10001 G Check all that apply: L_J Initial return L_J Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here Final return Amended return 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Add ress change Name change check here and attach computation H Check type of organization : © Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated = Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method : L_J Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination ^p (from Part ll, col (c), line 16) 0 Other ( specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here o 00.$ 17 9 , 15 0 , 3 8 9 . -

From Generosity to Justice, a New Gospel of Wealth

FROM GENEROSITY TO JUSTICE TO GENEROSITY FROM Pr a ise for From Generosity to Justice ndrew Carnegie wrote “The Gospel of “This will become a defining manifesto of our era.” A Wealth” in 1889, during the height of the —Walter Isaacson Gilded Age, when 4,000 American families controlled almost as much wealth as the rest of “Walker bravely tackles the subject of inequality with one pressing FROM the country combined. His essay laid the foun- Darren Walker is president of the Ford question in mind: What can philanthropy do about it?” dation for modern philanthropy. Foundation, a $13 billion international social justice —Ken Chenault Today, we find ourselves in a new Gilded philanthropy. He is co-founder and chair of the U.S. Age—defined by levels of inequality that sur- Impact Investing Alliance and the Presidents’ Council “A recalibration and reimagination of the philanthropic model crafted pass those of Carnegie’s time. The widening on Disability Inclusion in Philanthropy. by the Carnegie and Rockefeller families over a century ago. This new GENEROSITY chasm between the advantaged and the disad- Before joining Ford, Darren was vice president at the gospel must be heard all over the world!” vantaged demands our immediate attention. Rockefeller Foundation, overseeing global and domestic —David Rockefeller, Jr. Now is the time for a new Gospel of Wealth. programs. In the 1990s, he was COO of the Abyssinian In From Generosity to Justice: A New Gos- Development Corporation, Harlem’s largest community “Orchestrating a dynamic chorus of vital voices and vibrant vision, pel of Wealth, Darren Walker, president of the development organization. -

Kalamazoo College Harry T

DonorHonor2012-2013 Roll July 1, 2012 - June 30, 2013 Kalamazoo, Michigan Associate Science Director for Research, Marketing Trustees Hans P. Morefield ’92 and Extramural Programs Senior Vice President, Strategic Members of the Board Walter Reed Army Institute of Partnerships Alexandra F. Altman ‘97 Research SCI Solutions Chicago, Illinois Silver Spring, Maryland Katonah, New York Eugene V. N. Bissell ‘76 Donald R. Parfet Gladwyne, Pennsylvania Emeriti Trustees Managing Director John W. Brown H’03 Roger E. Brownell ’68 Apjohn Group, LLC Portage, Michigan President Kalamazoo, Michigan Golf & Electric Carriages, Inc. Rosemary Brown Jody K. Olsen Fort Myers, Florida Portage, Michigan Visiting Professor University of Jevon A. Caldwell-Gross ‘04 Maryland Baltimore Lawrence D. Bryan Pastor Baltimore, Maryland Martinsville, Indiana Hamilton Memorial United Methodist Gail A. Raiman ‘73 Phillip C. Carra ’69 Church Arlington, Virginia Fennville, Michigan Atlantic City, New Jersey Christopher P. Reynolds ‘83 Joyce K. Coleman ’66 Erin M.P. Charnley ‘02 General Counsel and Chief Legal Dallas, Texas Dentist Officer Blue Water Dentistry, PLC James H. C. Duncan, Sr. Toyota Motor Sales, USA Inc. Hudsonville, Michigan Santa Fe, New Mexico Torrance, California James A. Clayton ‘78 Marlene C. Francis ’58 William C. Richardson Senior Managing Director Ann Arbor, Michigan College Professor of Policy General Electric Capital Kalamazoo College Harry T. Garland ’68 Norwalk, Connecticut Kalamazoo, Michigan Los Altos Hills, California Amy S. Courter ’83 James A. Robideau ’76 Alfred J. Gemrich ’60 President General Manager Kalamazoo, Michigan International Air Cadet Tecumseh Packaging Solutions, Inc. Exchange Association Otha Gilyard H’01 Van Wert, Ohio Ottawa, Ontario, Canada Columbus, Ohio Mary Beth Sarhatt Harold J. -

Democracy Alliance Does America: the Soros-Founded Plutocrats’ Club Forms State Chapters by Matthew Vadum and James Dellinger

The Democracy Alliance Does America: The Soros-Founded Plutocrats’ Club Forms State Chapters By Matthew Vadum and James Dellinger (Editor’s note: This special report on the Democracy Alliance updates our January 2008 and December 2006 issues of Foun- dation Watch.) Summary: Four years ago the Democratic Party was in disarray after failing to reclaim the White House and Congress despite re- cord contributions by high-dollar donors. George Soros and other wealthy liberals decided they had the answer to the party’s problems. They formed a secretive donors’ collaborative to fund a permanent political infrastructure of nonprofi t think tanks, me- dia outlets, leadership schools, and activ- ist groups to compete with the conservative movement. Called the Democracy Alliance (DA), Soros and his colleagues put their im- primatur on the party and the progressive movement by steering hundreds of millions of dollars to liberal nonprofi ts they favored. The Democracy Alliance helped Democrats Democracy Alliance fi nancier George Soros spoofed: This is a screen grab from the give Republicans a shellacking in Novem- Oct. 4 “Saturday Night Live.” In front row from left to right, Kristen Wiig as House ber. Now it’s organizing state-level chapters Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Will Forte as Soros, and Fred Armisen as Rep. Barney Frank. in at least 19 states, and once-conservative could weaken the resolve of self-styled “pro- D.C., according to Marc Ambinder of the Colorado, which hosts the Democracy Al- gressives.” They worry that complacency Atlantic. It’s safe to say they are planning liance’s most successful state affi liate, has and fatalism threaten the progressive sense their next moves. -

Education and Economic Renewal in Kalamazoo

Upjohn Press Upjohn Research home page 1-1-2009 The Power of a Promise: Education and Economic Renewal in Kalamazoo Michelle Miller-Adams W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, [email protected] Upjohn Author(s) ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6869-9063 Follow this and additional works at: https://research.upjohn.org/up_press Part of the Education Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Citation Miller-Adams, Michelle. 2009. The Power of a Promise: Education and Economic Renewal in Kalamazoo. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. https://doi.org/10.17848/ 9781441612656 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. This title is brought to you by the Upjohn Institute. For more information, please contact [email protected]. § § § “Michelle Miller-Adams captures the truly unique story of the Kalamazoo Promise without losing sight of the universal lessons it offers us. The Power of a Promise is essential reading for anyone who wants to understand the future of economic and com- munity development in our country.” –Governor Jennifer M. Granholm, State of Michigan “The Kalamazoo Promise is a fascinating experiment with enormous implications for American education. Will the promise of free tuition inspire students to work harder in school? Will it draw more middle-class families back into the city’s public school system, enriching the learning environment for all? Michelle Miller-Adams provides a superb, thoroughly researched, and highly readable account of this closely watched, groundbreaking venture.” –Richard D. Kahlenberg, senior fellow, The Century Foundation and author of All Together Now: Creating Middle-Class Schools through Public School Choice “Across America, economic developers struggle to overcome the disincentives created by low-performance, poverty-impacted school districts. -

Philanthropy Roadmap

Y O U R PHILANTHROPY ROADMAP ROCKEFELLER PHILANTHROPY ADVISORS This brief guide is DOING GOOD & FEELING GOOD DOING IT SIDNEY FRANK designed to introduce you nown as the “$2 billion man” London, he helped fund an exhibition to the world of thoughtful, after selling Grey Goose at the London Science Museum K Vodka to Bacardi, Sidney honoring the engineer who designed effective philanthropy. Frank was a marketing wizard. All the Spitfire airplane, a machine that his life, Sidney displayed enthusiasm, many credit as the deciding factor It’s a roadmap for donors — creativity, and the ability to spot in the Battle of Britain. He was also potential — characteristics that drove inspired by his heritage and the region individuals, couples, his business success and defined in which he lived, and gave generously his giving. He famously rebranded to Jewish causes and his local families or groups. It offers Jägermeister in the 1980s, and community. “My father believed one followed up this success with the individual could change the world,” an overview of issues that launch of Grey Goose Vodka. By said Cathy Frank Halstead, Sidney’s the time he sold the brand in 2004, daughter, who is closely involved in philanthropists may want to he had established a strong financial his foundation. Sidney himself, who foundation for his philanthropic passed away in 2006, saw it this way: consider as they create their endeavors. “I just love giving money away.” own giving strategies. Sidney’s giving was tied closely to the events that shaped his life. As a young man in the 1930s, he left Brown “I just love Here you will find pertinent questions to help you determine if University after only one year because philanthropy is a destination you want to put on your itinerary. -

Justice for Chimpanzees and Communities

A R C U S F O U N D A T I O N 0 6 A N N U A L R E P O R T www.arcusfoundation.org Mission Statement The Arcus Foundation envisions and contributes to a pluralistic world that celebrates diversity and dignity, invests in social justice and promotes tolerance and compassion. The Arcus Great Apes Fund works to conserve great ape habitat in Africa (left and center), Former bio-med chimp Casey on his cross-country journey to Save the Chimps sanctuary (right) We Believe All individuals have a right and responsibility to full participation in our society. Education and knowledge can be antidotes to intolerance and bigotry. All members of the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender (GLBT) community deserve to be welcomed, celebrated and to become an integral part of a healthy society. All non-human animals have the right to live free of human cruelty and abuse. We all have a responsibility to work for a healthy and sustainable natural environment. Investing in youth is essential for their future and our community. We should strive to develop an attitude of acceptance, appreciation and affirmation of all forms of diversity. Southwest Michigan is a great place to live, work and grow, and is worthy of our investment of time, money and talents. Diversity, Justice, Compassion, Pluralism, and Freedom are core values that guide the work of the Arcus Foundation every day. Specifically, we support organizations that seek to achieve social justice that is inclusive of sexual orientation, gender identity and race through work on religion and values, racial justice and GLBT human rights. -

Campaign Finance Talk the Voice of the Michigan Campaign Finance Network August 2007

Campaign Finance Talk The Voice of the Michigan Campaign Finance Network www.mcfn.org August 2007 Who is Howie Rich? And what is he doing in Michigan? by Rich Robinson ith almost $200 million in political spending in Howie Rich’s history in Michigan goes back at least Michigan in 2006, it’s inevitable that some stories 15 years to our term limits initiative, to which Rich was Wdidn’t get the attention they deserved. The committee a significant financial contributor. In addition to the SOS behind the Stop OverSpending (SOS) Michigan ballot initiative work in 2006, his presence was felt in the 7th Congressional gained some notoriety because its petitions were insufficient to District Republican primary election, where Club for gain access to the ballot. The money story behind SOS, part of Growth, of which he is a director, supplied 90 percent of a sprawling national story that largely passed below the public the funds for Tim Walberg’s successful challenge against radar, is worthy of review. then-incumbent Joe Schwarz. Three out-of-state nonprofits put $1,088,000 into SOS, Howie Rich is present in Michigan today in the form of 99 percent of its funds. Two of those committees, Fund for the over-sized pig that Leon Drolet pulls around the state to Democracy ($623,000) and America at Its Best ($310,000), attract media attention for his threatened recalls against any are directed by a libertarian activist from New York legislators who support a tax increase. That same pig was City named Howie Rich. Howie Rich-related nonprofits used in Rich’s campaigns around the country in 2006, at provided substantial funding – in some cases nearly all the least as far west as Montana. -

The Money Behind the 2006 Marriage Amendments

THE MONEY BEHIND THE 2006 MARRIAGE AMENDMENTS By MEGA N MOO RE JULY 23 , 2007 This publication was made possible by grants from: JEHT Foundation, Fair and Participatory Elections Carnegie Corporation of New York, Strengthening U.S. Democracy Ford Foundation, Program on Governance and Civil Society The Pew Charitable Trusts, State Policy Initiatives Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Program on Democratic Practice 833 NORTH LAST CHANCE GULCH, SECOND FLOOR • HELENA, MT • 59601 PHONE 406-449-2480 • FAX 406-457-2091 • E-MAIL [email protected] www.followthemoney.org TA BLE OF CON TENTS Overview..................................................................................................3 The Political Climate................................................................................6 Those in Favor of the Same-Sex Marriage Bans .......................................7 Those Against the Same-Sex Marriage Bans...........................................10 Top Contributors Across the States………………………………………15 State-By-State Summaries Alabama .....................................................................................17 Arizona.......................................................................................18 Colorado.....................................................................................22 Idaho ..........................................................................................26 South Carolina............................................................................28 South Dakota ..............................................................................30 -

The Billionaires Behind the LGBT Movement | Jennifer Bilek | First

Support FIRST THINGS by turning your adblocker off or by making a donation. Thanks! forgot password?| register Email Password LOGIN CLOSE LOGIN / ACTIVATE SUBSCRIBE PRINT EDITION WEB CONTENT EVENTS MEDIA AUTHORS STORE ABOUT DONATE THE BILLIONAIRES BEHIND THE LGBT MOVEMENT by Jennifer Bilek 1 . 21 . 20 AMERICA'S MOST INFLUENTIAL ot long ago, the gay rights movement was a small group of people JOURNAL OF struggling to follow their dispositions within a larger heterosexual culture. Gays and lesbians were underdogs, vastly outnumbered and RELIGION AND loosely organized, sometimes subject to discrimination and PUBLIC LIFE N abuse. Their story was tragic, their suffering dramatized by AIDS and Rock Hudson, Brokeback Mountain and Matthew Shepard. Today’s movement, however, looks nothing like that band of persecuted outcasts. The LGBT rights agenda—note the addition of “T”—has become a powerful, aggressive force in American society. Its advocates stand at the top of media, academia, the professions, and, most important, SUBSCRIBE Big Business and Big Philanthropy. Consider the following case. LATEST ISSUE Jon Stryker is the grandson of Homer Stryker, an orthopedic surgeon who SUPPORT FIRST THINGS founded the Stryker Corporation. Based in Kalamazoo, Michigan, the Stryker Corporation sold $13.6 billion in surgical supplies and software in 2018. Jon, heir to the fortune, is gay. In 2000 he created the Arcus ADVERTISEMENT Foundation, a nonprofit serving the LGBT community, because of his own experience coming out as homosexual. Arcus has given more than $58.4 million to programs and organizations doing LGBT-related work between 2007 and 2010 alone, making it one of the largest LGBT funders in the world.