Union Busted: Understanding the Relationship Between Democrats, Republicans, and Teachers’ Unions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

2006 Ballot Measure Overview

2006 BALLOT MEASURE OVERVIEW AN A NALYSIS O F TH E MON EY RAISED A RO UND MEASU RES O N STA TE BA LLO TS I N 2006 By THE N ATIO NA L IN STI TU TE O N MON EY IN STA TE PO LI TI CS NOVEMBER 5, 2007 833 NORTH LAST CHANCE GULCH, SECOND FLOOR • HELENA, MT • 59601 PHONE 406-449-2480 • FAX 406-457-2091 • E-MAIL [email protected] www.followthemoney.org The National Institute on Money in State Politics is the only nonpartisan, nonprofit organization revealing the influence of campaign money on state-level elections and public policy in all 50 states. Our comprehensive and verifiable campaign-finance database and relevant issue analyses are available for free through our Web site FollowTheMoney.org. We encourage transparency and promote independent investigation of state-level campaign contributions by journalists, academic researchers, public-interest groups, government agencies, policymakers, students and the public at large. 833 North Last Chance Gulch, Second Floor • Helena, MT 59601 Phone: 406-449-2480 • Fax: 406-457-2091 E-mail: [email protected] www.FollowTheMoney.org This publication was made possible by grants from: JEHT Foundation, Fair and Participatory Elections Carnegie Corporation of New York, Strengthening U.S. Democracy Ford Foundation, Program on Governance and Civil Society The Pew Charitable Trusts, State Policy Initiatives Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Program on Democratic Practice The statements made and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the Institute. National Institute on Money in State Politics -

A POLITICAL THEORY of POPULISM* Daron Acemoglu Georgy Egorov Konstantin Sonin I. Introduction There Has Recently Been a Resurgen

A POLITICAL THEORY OF POPULISM* Daron Acemoglu Georgy Egorov Konstantin Sonin When voters fear that politicians may be influenced or corrupted by the rich elite, signals of integrity are valuable. As a consequence, an honest polit- ician seeking reelection chooses ‘‘populist’’ policies—that is, policies to the left of the median voter—as a way of signaling that he is not beholden to the interests of the right. Politicians that are influenced by right-wing special interests re- Downloaded from spond by choosing moderate or even left-of-center policies. This populist bias of policy is greater when the value of remaining in office is higher for the polit- ician; when there is greater polarization between the policy preferences of the median voter and right-wing special interests; when politicians are perceived as more likely to be corrupt; when there is an intermediate amount of noise in the information that voters receive; when politicians are more forward-looking; and http://qje.oxfordjournals.org/ when there is greater uncertainty about the type of the incumbent. We also show that soft term limits may exacerbate, rather than reduce, the populist bias of policies. JEL Codes: D71, D74. I. Introduction There has recently been a resurgence of ‘‘populist’’ politicians in several developing countries, particularly in Latin America. at MIT Libraries on April 24, 2013 Hugo Cha´vez in Venezuela, the Kirchners in Argentina, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Alan Garcı´a in Peru, and Rafael Correa in Ecuador are some of the examples. The label populist is often -

Arcus Foundation 2012 Annual Report the Arcus Foundation Is a Leading Global Foundation Advancing Pressing Social Justice and Conservation Issues

ConservationSocialJustice Arcus Foundation 2012 Annual Report The Arcus Foundation is a leading global foundation advancing pressing social justice and conservation issues. The creation of a more just and humane world, based on diversity, Arcus works to advance LGBT equality, as well as to conserve and protect the great apes. equality, and fundamental respect. L etter from Jon Stryker 02 L etter from Kevin Jennings 03 New York, U.S. Cambridge, U.K. Great Apes 04 44 West 28th Street, 17th Floor Wellington House, East Road New York, NY 10001 U.S. Cambridge CB1 1BH, U.K. Great Apes–Grantees 22 Phone +1.212.488.3000 Phone +44.1223.451050 Fax + 1. 212.488.3010 Fax +44.1223.451100 Strategy 24 [email protected] [email protected] F inancials / Board & Staff ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: © Emerson, Wajdowicz Studios / NYC / www.DesignEWS.com EDITORIAL TEAM: Editor, Sebastian Naidoo Writers, Barbara Kancelbaum & Susanne Morrell 25 THANK YOU TO OUR GRANTEES, PARTNERS, AND FRIENDS WHO CONTRIBUTED TO THE CONTENT OF THIS REPORT. © 2013 Arcus Foundation Front cover photo © Jurek Wajdowicz, Inside front cover photo © Isla Davidson Movements—whether social justice, animal conservation, or any other—take time and a sustained sense of urgency, In 2012 alone, we partnered with commitment, and fortitude. more than 110 courageous organizations hotos © Jurek Wajdowicz hotos © Jurek P working in over 40 countries around the globe. Dear Friends, Dear Friends, As I write this letter we are approaching the number 880, which represents a nearly 400 Looking back on some of the significant of the Congo. Continued habitat loss, spillover 50th anniversary of Dr. -

An International Journal for Students of Theological and Religious Studies Volume 36 Issue 3 November 2011

An International Journal for Students of Theological and Religious Studies Volume 36 Issue 3 November 2011 EDITORIAL: Spiritual Disciplines 377 D. A. Carson Jonathan Edwards: A Missionary? 380 Jonathan Gibson That All May Honour the Son: Holding Out for a 403 Deeper Christocentrism Andrew Moody An Evaluation of the 2011 Edition of the 415 New International Version Rodney J. Decker Pastoral PENSÉES: Friends: The One with Jesus, 457 Martha, and Mary; An Answer to Kierkegaard Melvin Tinker Book Reviews 468 DESCRIPTION Themelios is an international evangelical theological journal that expounds and defends the historic Christian faith. Its primary audience is theological students and pastors, though scholars read it as well. It was formerly a print journal operated by RTSF/UCCF in the UK, and it became a digital journal operated by The Gospel Coalition in 2008. The new editorial team seeks to preserve representation, in both essayists and reviewers, from both sides of the Atlantic. Themelios is published three times a year exclusively online at www.theGospelCoalition.org. It is presented in two formats: PDF (for citing pagination) and HTML (for greater accessibility, usability, and infiltration in search engines). Themelios is copyrighted by The Gospel Coalition. Readers are free to use it and circulate it in digital form without further permission (any print use requires further written permission), but they must acknowledge the source and, of course, not change the content. EDITORS BOOK ReVIEW EDITORS Systematic Theology and Bioethics Hans -

THE REPUBLICAN PARTY's MARCH to the RIGHT Cliff Checs Ter

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 29 | Number 4 Article 13 2002 EXTREMELY MOTIVATED: THE REPUBLICAN PARTY'S MARCH TO THE RIGHT Cliff checS ter Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Accounting Law Commons Recommended Citation Cliff cheS cter, EXTREMELY MOTIVATED: THE REPUBLICAN PARTY'S MARCH TO THE RIGHT, 29 Fordham Urb. L.J. 1663 (2002). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol29/iss4/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXTREMELY MOTIVATED: THE REPUBLICAN PARTY'S MARCH TO THE RIGHT Cover Page Footnote Cliff cheS cter is a political consultant and public affairs writer. Cliff asw initially a frustrated Rockefeller Republican who now casts his lot with the New Democratic Movement of the Democratic Party. This article is available in Fordham Urban Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol29/iss4/13 EXTREMELY MOTIVATED: THE REPUBLICAN PARTY'S MARCH TO THE RIGHT by Cliff Schecter* 1. STILL A ROCK PARTY In the 2000 film The Contender, Senator Lane Hanson, por- trayed by Joan Allen, explains what catalyzed her switch from the Grand Old Party ("GOP") to the Democratic side of the aisle. During her dramatic Senate confirmation hearing for vice-presi- dent, she laments that "The Republican Party had shifted from the ideals I cherished in my youth." She lists those cherished ideals as "a woman's right to choose, taking guns out of every home, campaign finance reform, and the separation of church and state." Although this statement reflects Hollywood's usual penchant for oversimplification, her point con- cerning the recession of moderation in Republican ranks is still ap- ropos. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

Behind Janus: Documents Reveal Decade-Long Plot to Kill Public-Sector Unions

Behind Janus: Documents Reveal Decade-Long Plot to Kill Public-Sector Unions The Supreme Court case Janus v. AFSCME is poised to decimate public-sector unions—and it’s been made possible by a network of right-wing billionaires, think tanks and corporations. MARY BOTTARI FEBRUARY 22, 2018 | MARCH ISSUE In These Times THE ROMAN GOD JANUS WAS KNOWN FOR HAVING TWO FACES. It is a fitting name for the U.S. Supreme Court case scheduled for oral arguments February 26, Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, Council 31, that could deal a devastating blow to public-sector unions and workers nationwide. In the past decade, a small group of people working for deep-pocketed corporate interests, conservative think tanks and right-wing foundations have bankrolled a series of lawsuits to end what they call “forced unionization.” They say they fight in the name of “free speech,” “worker rights” and “workplace freedom.” In briefs before the court, they present their public face: carefully selected and appealing plaintiffs like Illinois child-support worker Mark Janus and California schoolteacher Rebecca Friedrichs. The language they use is relentlessly pro-worker. Behind closed doors, a different face is revealed. Those same people cheer “defunding” and “bankrupting” unions to deal a “mortal blow” to progressive politics in America. A key director of this charade is the State Policy Network (SPN), whose game plan is revealed in a union-busting toolkit uncovered by the Center for Media and Democracy. The first rule of the national network of right-wing think tanks that are pushing to dismantle unions? “Rule #1: Be pro-worker, not anti-union. -

The Reality Behind the Rhetoric Surrounding the British

‘May Contain Nuts’? The reality behind the rhetoric surrounding the British Conservatives’ new group in the European Parliament Tim Bale, Seán Hanley, and Aleks Szczerbiak Forthcoming in Political Quarterly, January/March 2010 edition. Final version accepted for publication The British Conservative Party’s decision to leave the European Peoples’ Party-European Democrats (EPP-ED) group in the European Parliament (EP) and establish a new formation – the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) – has attracted a lot of criticism. Leading the charge have been the Labour government and left-liberal newspapers like the Guardian and the Observer, but there has been some ‘friendly fire’ as well. Former Conservative ministers - so-called ‘Tory grandees’ - and some of the party’s former MEPs have joined Foreign Office veterans in making their feelings known, as have media titles which are by no means consistently hostile to a Conservative Party that is at last looking likely to return to government.1 Much of the criticism originates from the suspicion that the refusal of other centre-right parties in Europe to countenance leaving the EPP has forced the Conservatives into an alliance with partners with whom they have – or at least should have – little in common. We question, or at least qualify, this assumption by looking in more detail at the other members of the ECR. We conclude that, while they are for the most part socially conservative, they are less extreme and more pragmatic than their media caricatures suggest. We also note that such caricatures ignore some interesting incompatibilities within the new group as a whole and between some of its Central and East European members and the Conservatives, not least 1 with regard to their foreign policy preoccupations and their by no means wholly hostile attitude to the European integration project. -

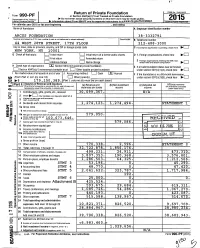

Return of Private Foundation

iN Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545.0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947( aXl) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter social security numbers on this form it may made public. Department of the Treasury ► as be 2015 internal Revenue Service lb, Information about Form 990-PF and its se parate instructions is at WwW.frS.gOV/fonn990pf. Open to im For calendar year 2015 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer Identification number ARCUS FOUNDATION 38-3332791 Number and street (or P 0 box number it marl is not delivered to street address) Room/sulte I B Telephone number 44 WEST 28TH STREET, 17TH FLOOR 212-488-3000 City or town, state or province, C if application country, and ZIP or foreign postal code exemption is pending , check here ► NEW YORK, NY 10001 G Check all that apply: L_J Initial return L_J Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here Final return Amended return 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Add ress change Name change check here and attach computation H Check type of organization : © Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated = Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method : L_J Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination ^p (from Part ll, col (c), line 16) 0 Other ( specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here o 00.$ 17 9 , 15 0 , 3 8 9 . -

![Critical Lessons from the Neoliberal / Neoconservative Take-Over Deniz Kellecioglu [United Nations Economic Commission for Africa,1 Ethiopia]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7208/critical-lessons-from-the-neoliberal-neoconservative-take-over-deniz-kellecioglu-united-nations-economic-commission-for-africa-1-ethiopia-1937208.webp)

Critical Lessons from the Neoliberal / Neoconservative Take-Over Deniz Kellecioglu [United Nations Economic Commission for Africa,1 Ethiopia]

real-world economics review, issue no. 85 subscribe for free How to transform economics and systems of power? Critical lessons from the neoliberal / neoconservative take-over Deniz Kellecioglu [United Nations Economic Commission for Africa,1 Ethiopia] Copyright: Deniz Kellecioglu 2018 You may post comments on this paper at https://rwer.wordpress.com/comments-on-rwer-issue-no-85/ Abstract This paper examines the transformation in economics during the 1970s in order to distil lessons to transformative efforts today. A historiography is developed around four spheres of change: ideas; corporations; politics; and the economics profession. This history is explained through three inter-connected phenomena of the time: ‘neoliberal economics’ (the intellectual backbone); ‘neoconservativism’ (the resulting power system); and ‘elite appropriations’ (the essential instrument of power). First, neoliberal economics ascended as a result of corporate reactions to deteriorating profits and policy influence, in conjunction with the broader economic and political crises. Secondly, neoconservative political elites ascended mainly through the support of economic elites, neoliberal economists, and effective voter strata that harboured negative norms, especially strict egoism, class elitism, sexism, and racism. Thirdly, the ideological gap between neoliberal economics and neoconservativism were strategically transcended by covert and overt power impositions, but especially through the appropriation of neoliberal ideas to achieve neoconservative results. Altogether, -

From Generosity to Justice, a New Gospel of Wealth

FROM GENEROSITY TO JUSTICE TO GENEROSITY FROM Pr a ise for From Generosity to Justice ndrew Carnegie wrote “The Gospel of “This will become a defining manifesto of our era.” A Wealth” in 1889, during the height of the —Walter Isaacson Gilded Age, when 4,000 American families controlled almost as much wealth as the rest of “Walker bravely tackles the subject of inequality with one pressing FROM the country combined. His essay laid the foun- Darren Walker is president of the Ford question in mind: What can philanthropy do about it?” dation for modern philanthropy. Foundation, a $13 billion international social justice —Ken Chenault Today, we find ourselves in a new Gilded philanthropy. He is co-founder and chair of the U.S. Age—defined by levels of inequality that sur- Impact Investing Alliance and the Presidents’ Council “A recalibration and reimagination of the philanthropic model crafted pass those of Carnegie’s time. The widening on Disability Inclusion in Philanthropy. by the Carnegie and Rockefeller families over a century ago. This new GENEROSITY chasm between the advantaged and the disad- Before joining Ford, Darren was vice president at the gospel must be heard all over the world!” vantaged demands our immediate attention. Rockefeller Foundation, overseeing global and domestic —David Rockefeller, Jr. Now is the time for a new Gospel of Wealth. programs. In the 1990s, he was COO of the Abyssinian In From Generosity to Justice: A New Gos- Development Corporation, Harlem’s largest community “Orchestrating a dynamic chorus of vital voices and vibrant vision, pel of Wealth, Darren Walker, president of the development organization.