Dodd/Structures of Colonialism/Jan13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ishikari Bay New Port 石狩湾新港

CLOSEST PORT to SAPPORO http://www.ishikari-bay-newport.jp ISHIKARI BAY NEW PORT 石狩湾 新 港 石狩湾新港管理組合 ISHIKARI BAY NEW PORT AUTHORITY 〒061-3244 北海道石狩市新港南2丁目725-1 725-1 Shinko-Minami 2 chome,Ishikari, Hokkaido, 061-3244, Japan Phone (0133)64-6661 Fax (0133)64-6666 2019.10 石狩湾新港 ヒト、モノ、コトが集まる港 石狩湾新港 石狩湾新港管理組合 管理者 A port where people, goods and events gather: Ishikari Bay Newport 鈴 木 直 道 Naomichi Suzuki President, Ishikari Bay New Port Authority 石狩湾新港の後背地で開催されている 野外ロックフェスティバル 「RISING SUN ROCK FESTIVAL」 An outdoor rock festival held behind Ishikari Bay 撮影協力DJI Newport: "RISING SUN ROCK FESTIVAL" RISING SUN ROCK FESTIVALは株式会社ウエスの登録商標です。 石狩湾新港は、日本海に臨む石狩湾沿岸のほぼ中央部 に位置し、北海道経済の中心地である札幌圏の海の玄関 です。 昭和57年に第1船が入港して以来、これまで東アジアと の間で定期コンテナ航路を開設するなど、本道の「日本海 側国際物流拠点」として機能を充実させてきたほか、近年 では、LNGの輸入や再生可能エネルギーの活用など「エネ ルギー基地」として拠点化を進め、取扱い貨物の堅調な推 移とともに着実な発展を続けております。 また、本港を核として整備された石狩湾新港地域には、 機械・金属・食品などの製造業、倉庫・運送などの流通業 など700社を超える多種多様な分野の企業が集積している ほか、北海道最大の冷凍冷蔵倉庫群があり、本道経済と 道民生活を支える生産と流通の拠点となっております。 石狩湾新港と新港地域が、これからも道央圏はもとより 本道経済のさらなる発展に寄与していくことができるよう、よ り利 用しやすい港づくりを積 極 的に進めてまいります。 Inauguration speech Ishikari Bay New Port is located in the middle section of the coast of Ishikari Bay that faces the Sea of Japan and serves as the water gateway for the Sapporo area, the center of Hokkaido's economy. Since the first ship entered the port in 1982, the port has enhanced its function as the "international distribution base on the side of the Sea of Japan" for Hokkaido through, for example, the operation of regular container services to East Asia. Recently it started to import LNG and utilize renewable energy in an effort to become an "energy base". The port has been steadily developing, with the stable transition of the volume of cargo handled. In addition, more than seven hundred companies in the manufacturing (machinery, metals and foods), logistics (warehousing and transportation) and other various industries are concentrated in the Ishikari Bay New Port Area, which has been developed around the port. -

Recent Developments in Local Railways in Japan Kiyohito Utsunomiya

Special Feature Recent Developments in Local Railways in Japan Kiyohito Utsunomiya Introduction National Railways (JNR) and its successor group of railway operators (the so-called JRs) in the late 1980s often became Japan has well-developed inter-city railway transport, as quasi-public railways funded in part by local government, exemplified by the shinkansen, as well as many commuter and those railways also faced management issues. As a railways in major urban areas. For these reasons, the overall result, approximately 670 km of track was closed between number of railway passengers is large and many railway 2000 and 2013. companies are managed as private-sector businesses However, a change in this trend has occurred in recent integrated with infrastructure. However, it will be no easy task years. Many lines still face closure, but the number of cases for private-sector operators to continue to run local railways where public support has rejuvenated local railways is sustainably into the future. rising and the drop in local railway users too is coming to a Outside major urban areas, the number of railway halt (Fig. 1). users is steadily decreasing in Japan amidst structural The next part of this article explains the system and changes, such as accelerating private vehicle ownership recent policy changes in Japan’s local railways, while and accompanying suburbanization, declining population, the third part introduces specific railways where new and declining birth rate. Local lines spun off from Japanese developments are being seen; the fourth part is a summary. Figure 1 Change in Local Railway Passenger Volumes (Unit: 10 Million Passengers) 55 50 45 Number of Passengers 40 35 30 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Fiscal Year Note: 70 companies excluding operators starting after FY1988 Source: Annual Report of Railway Statistics and Investigation by Railway Bureau Japan Railway & Transport Review No. -

METROS/U-BAHN Worldwide

METROS DER WELT/METROS OF THE WORLD STAND:31.12.2020/STATUS:31.12.2020 ّ :جمهورية مرص العرب ّية/ÄGYPTEN/EGYPT/DSCHUMHŪRIYYAT MISR AL-ʿARABIYYA :القاهرة/CAIRO/AL QAHIRAH ( حلوان)HELWAN-( المرج الجديد)LINE 1:NEW EL-MARG 25.12.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jmr5zRlqvHY DAR EL-SALAM-SAAD ZAGHLOUL 11:29 (RECHTES SEITENFENSTER/RIGHT WINDOW!) Altamas Mahmud 06.11.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6xG3hZccyg EL-DEMERDASH-SADAT (LINKES SEITENFENSTER/LEFT WINDOW!) 12:29 Mahmoud Bassam ( المنيب)EL MONIB-( ش ربا)LINE 2:SHUBRA 24.11.2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UCJA6bVKQ8 GIZA-FAYSAL (LINKES SEITENFENSTER/LEFT WINDOW!) 02:05 Bassem Nagm ( عتابا)ATTABA-( عدىل منصور)LINE 3:ADLY MANSOUR 21.08.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t7m5Z9g39ro EL NOZHA-ADLY MANSOUR (FENSTERBLICKE/WINDOW VIEWS!) 03:49 Hesham Mohamed ALGERIEN/ALGERIA/AL-DSCHUMHŪRĪYA AL-DSCHAZĀ'IRĪYA AD-DĪMŪGRĀTĪYA ASCH- َ /TAGDUDA TAZZAYRIT TAMAGDAYT TAỴERFANT/ الجمهورية الجزائرية الديمقراطيةالشعبية/SCHA'BĪYA ⵜⴰⴳⴷⵓⴷⴰ ⵜⴰⵣⵣⴰⵢⵔⵉⵜ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⴳⴷⴰⵢⵜ ⵜⴰⵖⴻⵔⴼⴰⵏⵜ : /DZAYER TAMANEỴT/ دزاير/DZAYER/مدينة الجزائر/ALGIER/ALGIERS/MADĪNAT AL DSCHAZĀ'IR ⴷⵣⴰⵢⴻⵔ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵏⴻⵖⵜ PLACE DE MARTYRS-( ع ني نعجة)AÏN NAÂDJA/( مركز الحراش)LINE:EL HARRACH CENTRE ( مكان دي مارت بز) 1 ARGENTINIEN/ARGENTINA/REPÚBLICA ARGENTINA: BUENOS AIRES: LINE:LINEA A:PLACA DE MAYO-SAN PEDRITO(SUBTE) 20.02.2011 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfUmJPEcBd4 PIEDRAS-PLAZA DE MAYO 02:47 Joselitonotion 13.05.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lJAhBo6YlY RIO DE JANEIRO-PUAN 07:27 Así es BUENOS AIRES 4K 04.12.2014 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PoUNwMT2DoI -

Tel. 0164-26-3111 71-12 Hirosato, Otoe-Cho, Fukagawa-Shi There Are Also Convenient and Discount Commuter Passes for Going to Work Or School

The routes and times change on April 1st 2020! Discounts Even more convenient access to the center of Fukagawa. New routes added! Children’s fare Discount for those with disabilities The fare for children elementary school age or Half price for those with younger is half the price of the adult fare*. disabilities Those in junior high and older must pay the adult fare. One caregiver is also half price per *The fare is rounded up to the closest unit of 10 yen. person listed as a Category 1 in their Physical Disability Certificate or person Children elementary school age and younger are free of charge in the following cases! with an A Ranking on their Rehabilitation Certificate ●The fare for each child under elementary school age is free of charge per each passenger elementary school age or older (The small child The disability discount is applied only fare can be applied for elementary school ● when the Physical Disability students). Certificate can be confirmed at time of payment. ●Small children being carried while on the bus are free of charge. ●This cannot be used with other �Limited to the same area for each case. discounts. �Please inquire with a staff member if you have any questions. JunkanJunkan LineLine Contact information Bus, JR and taxi companies Via Fukagawa West High School Bus Please confirm the Fukagawa fixed route Via Akebono Fukagawa Branch, Sorachi Chuo Bus bus information when riding the bus. Tel. 0164-26-3111 71-12 Hirosato, Otoe-cho, Fukagawa-shi There are also convenient and discount commuter passes for going to work or school. -

A Journey Into the History and Culture of Hokkaido ҆ේᢋƹമӫ૩҅ǜߺǖଅ

A Journey into the History and Culture of Hokkaido ҆ේᢋƸമӫ૩҅ǜߺǕଅ A Journey Useful information for a journey into the History into the history and culture of Hokkaido Good Day Hokkaido and Culture Website featuring tourist information about Hokkaido (information on tourist destinations and events across Hokkaido, travel plans, etc.) ◆URL/http://www.visit-hokkaido.jp of Hokkaido …………………………………………………………………………………………………………Hokkaido Tourism Organization JNTO Tourist Information Offices List of tourist information offices with multilingual staff ◆URL/http://www.jnto.go.jp/eng/arrange/travel/guide/voffice.php …………………………………………………………………………………………Japan National Tourism Organization (JNTO) Must-have Handbook for Driving in Hokkaido A handbook for a safe, comfortable and pleasant car trip in Hokkaido (basic rules and manners, rental cars, traffic rules, driving on winter roads, how to deal with problems, etc.) ◆URL/http://www.hkd.mlit.go.jp/topics/toukei/chousa/h20keikaku/handbook.html ……………………Hokkaido Regional Development Bureau, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Drive Hokkaido ‒ Basic knowledge of traffic safety Information for driving safely in Hokkaido (safety-minded driving, basic rules and manners, driving on winter roads, what to do in a traffic accident, major road signs and traffic lights in Japan, etc.) ◆URL/http://www.pref.hokkaido.lg.jp/ks/dms/saftydrive/ ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………Hokkaido Government Northern Road Navi ‒ Road and Traveler Information in Hokkaido Hokkaido road information (road maps, information on -

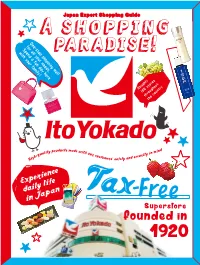

Ito-Yokado’S Basic Approach to Business

Japan Expert Shopping Guide This image illustrates Ito-Yokado’s basic approach to business. We started as a small sapling and grew into a large tree over 100 We aim to be a sincere We aim to be a sincere We aim to be a sincere In 2020, Ito-Yokado years. The doves on the tree’s branches represent all the company that company that our business company that stakeholders of our company—customers, business partners, our customers trust. partners, shareholders and our employees trust. and employees—who are gathered peacefully and keep our local communities trust. business going. will anniversary celebrate th as its 100 Products from the 1980’s Japan’s largest supers Did you one of tores know? 100 th Anniversary 2020 1st logo The history of 1958 -1964 Ito-Yokado opens our logo in a multi-story building occupying With your support, we celebrate the basement floor to the 6th floor. The Ito-Yokado logo design It stocks everything from features a dove, a symbol our 100th anniversary! 2nd logo 1964 -1972 everyday household items to of peace. It has been used clothes and groceries. since 1958. 2007 In the current logo, blue 1967 means a clear sky (future), Current logo 1972 onward We begin selling products under our original red means passion, and The company brand is born. “Seven Premium” brand white means sincerity. Originally a clothing store, 2011 we started with apparel Starting with only before expanding our lineup to food 49 items, Seven Premium 2013 and basic necessities. has since expanded to over 4,000 items including food, 2015 Surprisingly, there’s The first store in Kitasenju was small, with This laid the foundation for still a store in this only 6.6 square meters of retail space. -

Procedures from Filing to Registration of Trademark Application

Procedures from Filing to Registration of Trademark Application Japan Patent Office Asia-Pacific Industrial Property Center, JIII ©2006 Collaborator : Sadayuki HOSOI Patent Attorney, Eichi International Patent Office Table of Contents page Chapter I: Foreword ······················································································ 1 1. What is Intellectual Property? ······························································ 1 (Outline of intellectual property rights protected under each law) 2. What is a Trademark? ········································································ 2 (1) Trademark under the Japanese Trademark Law ································ 2 (2) Trademarks in Society and the Commercial World ·························· 2 3. Characteristics of the Japanese Trademark Law ··································· 2 Chapter II: Procedures from Filing to Registration of a Trademark Application ··················································································· 4 1. Preparations Before Filing a Trademark Application ··························· 4 (1) Determine the scope of goods (services) as well as designated goods (services) with consideration to the present and future business ···························································································· 4 (2) Select (its name) and design a trademark ·········································· 4 (3) Conduct a search for trademarks and goods/services (with consideration to requirements for registration, grounds for non-registration, -

Current Status of Hokkaido Shinkansen

Expansion of High-Speed Rail Services Current Status of Hokkaido Shinkansen Junichi Yorita Introduction also applied for development of about 211 km of line between Shin-Hakodate and Sapporo including Shin Aomori Station The Hokkaido Shinkansen is being developed in accordance to Sapporo Station, but some sections (where construction with the Nationwide Shinkansen Railway Development Act and had not started) are not approved yet. will have some 360 km of tracks from Shin Aomori Station (the Although part of the broad master plan for the Hokkaido new terminus of the Tohoku Shinkansen since 4 December Shinkansen, some sections between Sapporo and 2010) to Sapporo through Hakodate, Yakumo, Oshamambe, Asahikawa and the southern route (Oshamambe through Kutchan, and Otaru. It will also incorporate a line between Muroran to Sapporo) have not yet materialized. Sapporo and Asahikawa, and a line from Oshamambe through the vicinity of Muroran as a southern route. Background to Hokkaido Shinkansen The Japan Railway Construction, Transport and Development Plan Technology Agency (JRTT) applied for approval of the first 149 km of line between Shin Aomori and Shin-Hakodate In March 1967, the Sato Cabinet approved an economic in April 2005 and construction started subsequently with and social development plan that included a shinkansen completion scheduled for fiscal 2015. Along with the Shin construction initiative, marking the de facto start of the Aomori to Shin-Hakodate (provisional name) approval, JRTT current projected shinkansen lines. Two years -

Hokkaido Shuichi Takashima

Railwa Railway Operators Railway Operators in Japan 2 Hokkaido Shuichi Takashima Hokkaido as vast fields and verdant nature. profitable private railways in Hokkaido. Overview Amidst the Japanese economic recession, In the 1950s, several private railways Hokkaido is suffering from a stagnant hauled coals from Hokkaido’s coalmines, General description of Hokkaido economy. Moreover, the centralization and also provided local passenger Surrounded by the Pacific Ocean, the Sea of economic activity and population in services. However, most freight railways of Japan and the Sea of Okhotsk, Hokkaido Sapporo, the prefectural capital, is a closed after the decline of the coal is the northernmost island in the Japanese concern. For example, Sapporo has 1.76 industry and as private cars became archipelago with an area of 83,452 km2, million inhabitants while the second and increasingly common. y representing 22% of the nation’s total land third largest cities of Asahikawa and JR Hokkaido has three major railway area. Although Hokkaido is the largest of Hakodate have just 0.36 million and 0.30 functions––to link Sapporo with other all 47 prefectures in Japan, its population million, respectively. major cities in Hokkaido and the main is just 5.7 million, representing only about island of Honshu; to provide transport in Operators 4.5% of the national total—the population Outline of railways urban areas of Sapporo; and to provide density is just 20% of the average. Railways in Hokkaido have a total length local transport in other rural regions. Agriculture, fisheries, and forestry are the of 2702.0 km of which 2499.8 km (on 1 The four other private railway operators major industries, and the scenery is still April 2001) are operated by JR Hokkaido, in Hokkaido have just 202.2 route-km. -

From New Chitose Airport

Access From New Chitose Airport New Chitose Airport Sapporo by JR Line by Express Bus (rapid “Airport”) New Chitose Airport (40 minutes) (1 hour 10 minutes) JR Line: Sapporo Station ・ Subway: Sapporo Station by Subway Nanboku Line (2 minutes) Tokyo Kita 12-jo on foot Station (20 minutes) on foot (10 minutes) Osaka Hokkaido University [From New Chitose Airport [From Sapporo Station to Terminal to Sapporo Station] Hokkaido University] ■ JR ■ Subway Nanboku line by JR Line (rapid “Airport”)…40 minutes 10 minutes walk from Kita 12-jo station ■ by Express Bus …1 hour 10 minutes 15 minutes walk from Kita 18-jo station ■ 20 minutes walk from JR Sapporo Station Address/Contact Address Kita 14, Nishi 9, Kita-ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido, 060-0814, Japan Graduate School of Information Science and Technology, Hokkaido University Contact Graduate School of Information Science and Technology, Hokkaido University Fax : +81-11-706-7890 Campus Map N Kita 18-jo Station 18-jo Kita School of Veterinary Medicine Kita 18-jo Gate Nishi 5-chome Street Information Science and Technology 5 Hokkaido University Hospital School of Engineering Kita 12-jo Station 12-jo Kita 4 Kita 13-jo Gate 3 School of Science NanbokuSubway Line Faculty of Agriculture < To Otaru Bust of 2 Main Gate Dr.William S.Clark 1 JR Hakodate Main Line JR Sapporo Station Main Gate Bust of Dr. William Kita 13-jo Gate Entrance /School Guideboard at North S. Clark of Engineering Entrance/School of Engineering Guide map around Graduate School of Information Science and Technology 10 Graduate School of Information Science and Technology BLDG (high-rise) Faculty of Engineering M-BLDG (low-rise) 11 9 8 Quantum Electronics Quantum Integrated for Research Center School of Engineering 7 by Taxi by Laboratory Meme Media 6 Walk Main Entrance/School Approach in Robby/ Approach in 1st Floor/ of Engineering School of Engineering School of Engineering Entrance/Graduate School North Entrance/ Graduate School of of Information Science School of Engineering Information Science and and Technology BLDG Technology BLDG. -

Family Trip to Hokaido

Family trip to Hokaido Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Family trip to Hokaido Family trip in Hokaido travel inerary, the best things to do in Hokaido from Sapporo to Hakodate to Tomamu, top attractions in Hokaido. Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - From Tokyo to Sapporo Day Description: Arrive into Sapporo from Tokyo. Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - From Tokyo to Sapporo Rating: 4.1 1. New Chitose Airport 3. Sapporo Art Park Center Duration ~ 1 Hour Duration ~ 2 Hours Bibi, Chitose, Hokkaido 066-0012, Japan 2 Chome-2-75 Geijutsunomori, Minami-ku, Sapporo-shi, Hokkaidō 005-0864, Japan Telephone: +81 123-23-0111 Website: www.new-chitose-airport.jp Rating: 4.3 Monday: 9:45 AM – 5:00 PM Tuesday: 9:45 AM – 5:00 PM Wednesday: 9:45 AM – 5:00 PM 2. DORAEMON WAKUWAKU SKY PARK Thursday: 9:45 AM – 5:00 PM Friday: 9:45 AM – 5:00 PM Duration ~ 2 Hours Saturday: 9:45 AM – 5:00 PM Japan, 〒 066-0012 Hokkaidō, Chitose-shi, Bibi, 新千歳空港 Sunday: 9:45 AM – 5:00 PM 旅客ターミナルビル 連絡施設 3階 Telephone: +81 11-592-5111 Website: www.artpark.or.jp Monday: 10:00 AM – 6:30 PM Rating: 4.1 Tuesday: 10:00 AM – 6:30 PM Wednesday: 10:00 AM – 6:30 PM Thursday: 10:00 AM – 6:30 PM 4. Chocolatier Masále Friday: 10:00 AM – 6:30 PM Duration ~ 1 Hour Saturday: 10:00 AM – 6:30 PM Sunday: 10:00 AM – 6:30 PM Japan, 〒 060-0806 北海道札幌市北区北6条西2丁目 Telephone: +81 123-46-3355 Website: www.shinchitose-entame.jp Monday: 10:00 AM – 9:00 PM Rating: 4.3 Tuesday: 10:00 AM – 9:00 PM Wednesday: 10:00 AM – 9:00 PM If you are landing into the New Chitose airport, be sure to Thursday: 10:00 AM – 9:00 PM visit the Doraemon Waku Waku Sky Park (10:00-18:00, Friday: 10:00 AM – 9:00 PM ¥800pp) inside the airport. -

Mashike's Great Food

Wakkanai Access from Honshu By air Rumoi Asahikawa Tokyo to Wakkanai: 1 hour and 45 minutes Mashike Tokyo to Chitose: 1 hour and 30 minutes Tokyo to Asahikawa: 1 hour and 45 minutes Otaru By sea Sapporo Maizuru/Tsuruga to Otaru: 21 to 30 hours Chitose Niigata to Otaru: Approximately 18 hours (Shin Nihonkai Ferry, Phone: 0134-22-6191) Access from major cities in Hokkaido By car Tokyo From Sapporo Approximately 2 hours via the Fukagawa-Rumoi Expressway (approximately 130 kilometers) and Routes 233 and 231 (approximately 36 kilometers) Approximately 2 hours via Route 231 (110 kilometers) Approximately 2 hours and 30 minutes via Route 275, Prefectural Highway 94 and Route 231 (153 kilometers) MASHIKEMASHIKE From Asahikawa Approximately 1 hour and 30 minutes via the Fukagawa-Rumoi Expressway Traveling through history and nature (68 kilometers) and Routes 233 and 231 (36 kilometers) Approximately 2 hours via Routes 12, 233, and 231 (100 kilometers) From Wakkanai Approximately 3 hours and 50 minutes via Routes 40, 232, and 231 (210 kilometers) By JR lines From Sapporo (Hakodate Main Line – Rumoi Main Line) Approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes on the Rumoi Main Line via Fukagawa From Asahikawa (Hakodate Main Line – Rumoi Main Line) Approximately 1 hour and 40 minutes on the Rumoi Main Line via Fukagawa From Wakkanai (Soya Main Line – Hakodate Main Line – Rumoi Main Line) Approximately 5 hours and 20 minutes on the Rumoi Main Line via Fukagawa Tourist Information Tourism Promotion Office, Economic 0164-53-3332 Affairs Division, Mashike Town Mashike Tourist Association 0164-53-3332 Both phones are staffed from 9:00 a.m.