The Call of the Sidhe: Poetic and Mythological Influences in Ireland's Struggle for Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Celtic Encyclopedia, Volume II

7+( &(/7,& (1&<&/23(',$ 92/80( ,, . T H E C E L T I C E N C Y C L O P E D I A © HARRY MOUNTAIN VOLUME II UPUBLISH.COM 1998 Parkland, Florida, USA The Celtic Encyclopedia © 1997 Harry Mountain Individuals are encouraged to use the information in this book for discussion and scholarly research. The contents may be stored electronically or in hardcopy. However, the contents of this book may not be republished or redistributed in any form or format without the prior written permission of Harry Mountain. This is version 1.0 (1998) It is advisable to keep proof of purchase for future use. Harry Mountain can be reached via e-mail: [email protected] postal: Harry Mountain Apartado 2021, 3810 Aveiro, PORTUGAL Internet: http://www.CeltSite.com UPUBLISH.COM 1998 UPUBLISH.COM is a division of Dissertation.com ISBN: 1-58112-889-4 (set) ISBN: 1-58112-890-8 (vol. I) ISBN: 1-58112-891-6 (vol. II) ISBN: 1-58112-892-4 (vol. III) ISBN: 1-58112-893-2 (vol. IV) ISBN: 1-58112-894-0 (vol. V) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mountain, Harry, 1947– The Celtic encyclopedia / Harry Mountain. – Version 1.0 p. 1392 cm. Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-58112-889-4 (set). -– ISBN 1-58112-890-8 (v. 1). -- ISBN 1-58112-891-6 (v. 2). –- ISBN 1-58112-892-4 (v. 3). –- ISBN 1-58112-893-2 (v. 4). –- ISBN 1-58112-894-0 (v. 5). Celts—Encyclopedias. I. Title. D70.M67 1998-06-28 909’.04916—dc21 98-20788 CIP The Celtic Encyclopedia is dedicated to Rosemary who made all things possible . -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

Sponsorship Opportunity: I Am Ireland Film For

the Irish Fellowship Club of Chicago presents A concert being presented at Old Saint Pat’s in Chicago for broadcast on PBS “There will be all manner of celebrations during next year’s centennial but it’s hard – almost impossible – to imagine any will be as moving, entertaining, enlightening or soaring as I AM IRELAND.” – rick kogan, the chicago tribune I AM IRELAND The History of Ireland’s Road to Freedom 1798 ~ 1916 “As told through songs of her people” TELLING THE STORY OF IRISH INDEPENDENCE AND CREATING A LEGACY THAT WILL LIVE FOR GENERATIONS TO COME he goal of the I AM IRELAND show is to record the story of Ireland’s road to freedom filmed before a live audience at Old St. TPatrick’s Church in Chicago over a three-day period in the Fall of 2019, for distribution through the PBS Television Network. We are seek- ing to raise $500,000 to cover the cost of this production while simulta- neously raising scholarship funds for the Irish Fellowship Educational and Cultural Foundation. This filming and recording will be carried out by the acclaimed HMS Media Group, who recently filmed for broadcast the highly rated Chicago Voices Concert, (2017) featuring Renée Fleming and more recently, Jesus Christ Superstar for PBS. The I AM IRELAND show will feature traditional Irish Tenor Paddy Homan, together with 35 musicians from The City Lights Orchestra, under the direction of Rich Daniels. Additionally, there will be three traditional Irish musicians, along with an All-Ireland traditional Irish step dancer. The ninety-minute show takes audiences on a journey through the songs and speeches of Ireland’s road to freedom between 1798 and 1916. -

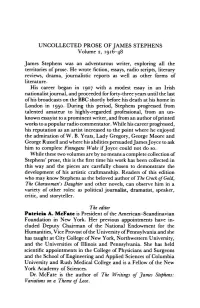

UNCOLLECTED PROSE of JAMES STEPHENS Volume 2, 1916-48

UNCOLLECTED PROSE OF JAMES STEPHENS Volume 2, 1916-48 James Stephens was an adventurous writer, exploring all the territories of prose. He wrote fiction, essays, radio scripts, literary reviews, drama, journalistic reports as well as other forms of literature. His career began in 1907 with a modest essay in an Irish nationalist journal, and proceeded for forty-three years until the last of his broadcasts on the BBC shortly before his death at his home in London in 1950. During this period, Stephens progressed from talented amateur to highly-regarded professional, from an un known essayist to a prominent writer, and from an author of printed works to a popular radio commentator. While his career progi-essed, his reputation as an artist increased to the point where he enjoyed the admiration ofW. B. Yeats, Lady Gregory, George Moore and George Russell and where his abilities persuaded James Joyce to ask him to complete Finnegans Wake if Joyce could not do so. While these two volumes are by no means a complete collection of Stephens' prose, this is the first time his work has been collected in this way and the pieces are carefully chosen to demonstrate the development of his artistic craftmanship. Readers of this edition who may know Stephens as the beloved author of The Crock oJGold, The Charwoman's Daughter and other novels, can observe him in a variety of other roles: as political journalist, dramatist, speaker, critic, and storyteller. The editor Patricia A. McFate is President of the American-Scandinavian Foundation in New York. Her previous appointments have in cluded Deputy Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Vice Provost of the University of Pennsylvania and she has taught at City College of New York, Northwestern University, and the Universities of Illinois and Pennsylvania. -

Imeacht Na Niarlí the Flight of the Earls 1607 - 2007 Imeacht Na Niarlí | the Flight of the Earls

Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich Roddy Hegarty Memorial Library & Archive Imeacht Na nIarlí The Flight of the Earls 1607 - 2007 Imeacht Na nIarlí | The Flight of the Earls Introduction 1 The Nine Years War 3 Imeacht na nIarlaí - The Flight of the Earls 9 Destruction by Peace 17 Those who left Ireland in 1607 23 Lament for Lost Leaders 24 This publication and the education and outreach project of Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich Memorial Library & Archive, of which it forms part, have been generously supported by Heritage Lottery Fund Front cover image ‘Flight of the Earls’ sculpture in Rathmullan by John Behan | Picture by John Campbell - Strabane Imeacht Na nIarlí | The Flight of the Earls Introduction “Beside the wave, in Donegal, The face of Ireland changed in September 1607 when and outreach programme supported by the Heritage the Earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell along with their Lottery Fund. The emphasis of that exhibition was to In Antrim’s glen or far Dromore, companions stept aboard a ship at Portnamurry near bring the material held within the library and archive Or Killillee, Rathmullan on the shores of Lough Swilly and departed relating to the flight and the personalities involved to a their native land for the continent. As the Annals of wider audience. Or where the sunny waters fall, the Four Masters records ‘Good the ship-load that was In 2009, to examine how those events played a role At Assaroe, near Erna’s shore, there, for it is certain that the sea has never carried in laying the foundation for the subsequent Ulster nor the wind blown from Ireland in recent times a This could not be. -

1 GENETIC JOYCE STUDIES – Issue 21 (Spring 2021) Source

GENETIC JOYCE STUDIES – Issue 21 (Spring 2021) Source Emendations in Gem Thief, Notebook VI.B.1: Topography of Ireland and Handbook of the Ulster Question Viviana-Mirela Braslasu and Geert Lernout Gerard of Wales or Giraldus Cambrensis was a Welsh-Norman priest, clerk of Henry II and writer of scholarly works. As a relative of some of the Normans who had invaded Ireland a generation earlier he visited the island on a number of occasions and he wrote an account of the Norman invasion, preceded by what he called a Topographia, a description of Ireland and the Irish, which he considered a barbarous people, which in itself justified the Norman invasion. This is the first book about Ireland by a non-resident and as Joep Leerssen has demonstrated, it stands at the beginning of a long tradition of negative images of the Irish. Joyce refers to Cambrensis in A Portrait when Temple tells young Dedalus that his family is mentioned by Geraldus and in Ulysses when the Citizen claims that Cambrensis described the sophistication and wealth of the nation, especially its exports among which he includes wine, whereas Cambrensis explicitly says that contrary to what the Venerable Bede claimed, there are no vineyards in Ireland. It is clear that the material Joyce borrows from Cambrensis is the most fantastic and silly bits, such as that there are no mice, no earthquakes and ospreys that have a talon and a webbed foot. The second book was a very recent production, part of the Free State’s campaign over the lost province and its cultural, social and political role in a united Ireland. -

Urban Planning, Irish Modernism, and Dublin

Notes 1 Urbanizing the Revival: Urban Planning, Irish Modernism, and Dublin 1. Arguably Andrew Thacker betrays a similar underlying assumption when he writes of ‘After the Race’: ‘Despite the characterisation of Doyle as a rather shallow enthusiast for motoring, the excitement of the car’s “rapid motion through space” is clearly associated by Joyce with a European modernity to which he, as a writer, aspired’ (Thacker 115). 2. Wirth-Nesher’s understanding of the city, here, is influenced by that of Georg Simmel, whereby the city, while divesting individuals of a sense of communal belonging, also affords them a degree of personal freedom that is impossible in a smaller community (Wirth-Nesher 163). Due to the lack of anonymity in Joyce’s Dublin, an indicator of its pre-urban or non-urban status, this personal freedom is unavailable to Joyce’s characters. ‘There are almost no strangers’ in Dubliners, she writes, with the exceptions of those in ‘An Encounter’ and ‘Araby’ (164). She then enumerates no less than seven strangers in the collection, arguing however that they are ‘invented through the transformation of the familiar into the strange’ (164). 3. Wirth-Nesher’s assumptions about Dublin’s status as a city are not really necessary to the focus of her analysis, which emphasizes the importance Joyce’s early work places on the ‘indeterminacy of the public and private’ and its effects on the social lives of the characters (166). That she chooses to frame this analysis in terms of Dublin’s ‘exacting the price of city life and in turn offering the constraints of a small town’ (173) reveals forcefully the pervasiveness of this type of reading of Joyce’s Dublin. -

The Dagda As Briugu in Cath Maige Tuired

Deep Blue Deep Blue https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/documents Research Collections Library (University of Michigan Library) 2012-05 Following a Fork in the Text: the Dagda as briugu in Cath Maige Tuired Martin, Scott A. https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/138967 Downloaded from Deep Blue, University of Michigan's institutional repository Following a Fork in the Text: the Dagda as briugu in Cath Maige Tuired Scott A. Martin, May 2012 The description of the Dagda in §93 of Cath Maige Tuired has become iconic: the giant, slovenly man in a too-short tunic and crude horsehide shoes, dragging a huge club behind him. Several aspects of this depiction are unique to this text, including the language used to describe the Dagda’s odd weapon. The text presents it as a gabol gicca rothach, which Gray translates as a “wheeled fork.” In every other mention of the Dagda’s club – including the other references in CMT (§93 and §119) – the term used is lorg. DIL gives significantly different fields of reference for the two terms: 2 lorg denotes a staff, rod, club, handle of an implement, or “the membrum virile” (thus enabling the scatological pun Slicht Loirge an Dagdai, “Track of the Dagda’s Club/Penis”), while gabul bears a variety of definitions generally attached to the concept of “forking.” The attested compounds for gabul include gabulgicce, “a pronged pole,” with references to both the CMT usage and staves held by Conaire’s swineherds in Togail Bruidne Da Derga. DIL also mentions several occurrences of gabullorc, “a forked or pronged pole or staff,” including an occurrence in TBDD (where an iron gabullorg is carried by the supernatural Fer Caille) and another in Bretha im Fuillema Gell (“Judgements on Pledge-Interests”). -

Hugh Macdiarmid and Sorley Maclean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters

Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters by Susan Ruth Wilson B.A., University of Toronto, 1986 M.A., University of Victoria, 1994 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Susan Ruth Wilson, 2007 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Dr. Iain Higgins_(English)__________________________________________ _ Supervisor Dr. Tom Cleary_(English)____________________________________________ Departmental Member Dr. Eric Miller__(English)__________________________________________ __ Departmental Member Dr. Paul Wood_ (History)________________________________________ ____ Outside Member Dr. Ann Dooley_ (Celtic Studies) __________________________________ External Examiner ABSTRACT This dissertation, Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters, transcribes and annotates 76 letters (65 hitherto unpublished), between MacDiarmid and MacLean. Four additional letters written by MacDiarmid’s second wife, Valda Grieve, to Sorley MacLean have also been included as they shed further light on the relationship which evolved between the two poets over the course of almost fifty years of friendship. These letters from Valda were archived with the unpublished correspondence from MacDiarmid which the Gaelic poet preserved. The critical introduction to the letters examines the significance of these poets’ literary collaboration in relation to the Scottish Renaissance and the Gaelic Literary Revival in Scotland, both movements following Ezra Pound’s Modernist maxim, “Make it new.” The first chapter, “Forging a Friendship”, situates the development of the men’s relationship in iii terms of each writer’s literary career, MacDiarmid already having achieved fame through his early lyrics and with the 1926 publication of A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle when they first met. -

James Stephens - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Stephens - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Stephens(9 February 1882 - 26 December 1950) James Stephens was an Irish novelist and poet. James Stephens produced many retellings of Irish myths and fairy tales. His retellings are marked by a rare combination of humor and lyricism (Deirdre, and Irish Fairy Tales are often especially praise). He also wrote several original novels (Crock of Gold, Etched in Moonlight, Demi-Gods) based loosely on Irish fairy tales. "Crock of Gold," in particular, achieved enduring popularity and was reprinted frequently throughout the author's lifetime. Stephens began his career as a poet with the tutelage of "Æ" (<a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/george-william-a-e-russell-2/">George William Russel</a>l). His first book of poems, "Insurrections," was published during 1909. His last book, "Kings and the Moon" (1938), was also a volume of verse. During the 1930s, Stephens had some acquaintance with <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/james-joyce/">James Joyce</a>, who found that they shared a birth year (and, Joyce mistakenly believed, a birthday). Joyce, who was concerned with his ability to finish what later became Finnegans Wake, proposed that Stephens assist him, with the authorship credited to JJ & S (James Joyce & Stephens, also a pun for the popular Irish whiskey made by John Jameson & Sons). The plan, however, was never implemented, as Joyce was able to complete the work on his own. During the last decade of his life, Stephens found a new audience through a series of broadcasts on the BBC. -

W. B. Yeat's Presence in James Joyce's a Portrait of The

udc 821.111-31.09 Joyce J. doi 10.18485/bells.2015.7.1 Michael McAteer Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Budapest, Hungary W. B. YEAT’S PRESENCE IN JAMES JOYCE’S A PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG MAN Abstract In the context of scholarly re-evaluations of James Joyce’s relation to the literary revival in Ireland at the start of the twentieth century, this essay examines the significance of W.B. Yeats to A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. It traces some of the debates around Celtic and Irish identity within the literary revival as a context for understanding the pre-occupations evident in Joyce’s novel, noting the significance of Yeats’s mysticism to the protagonist of Stephen Hero, and its persistence in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man later. The essay considers the theme of flight in relation to the poetry volume that is addressed directly in the novel, Yeats’s 1899 collection, The Wind Among the Reeds. In the process, the influence of Yeats’s thought and style is observed both in Stephen Dedalus’s forms of expression and in the means through which Joyce conveys them. Particular attention is drawn to the notion of enchantment in the novel, and its relation to the literature of the Irish Revival. The later part of the essay turns to the 1899 performance of Yeats’s play, The Countess Cathleen, at the Antient Concert Rooms in Dublin, and Joyce’s memory of the performance as represented through Stephen towards the end of the novel. -

John Bull's Other Ireland

John Bull’s Other Ireland: Manchester-Irish Identities and a Generation of Performance Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors O'Sullivan, Brendan M. Citation O'Sullivan, B. M. (2017). John Bull’s Other Ireland: Manchester- Irish identities and a generation of performance (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Publisher University of Chester Download date 28/09/2021 05:41:52 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/620650 John Bull’s Other Ireland Manchester-Irish Identities and a Generation of Performance Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Chester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Brendan Michael O’Sullivan May 2017 Declaration The material being presented for examination is my own work and has not been submitted for an award of this, or any other HEI except in minor particulars which are explicitly noted in the body of the thesis. Where research pertaining to the thesis has been undertaken collaboratively, the nature of my individual contribution has been made explicit. ii Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................... 2 Locating Theory and Method in Performance Studies and Ethnography. .. 2 Chapter 1 ..................................................................................................... 12 Forgotten but not Gone ............................................................................ 12 Chapter 2 ....................................................................................................