Editing Nature in Grand Canyon National Park Postcards*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grand-Canyon-South-Rim-Map.Pdf

North Rim (see enlargement above) KAIBAB PLATEAU Point Imperial KAIBAB PLATEAU 8803ft Grama Point 2683 m Dragon Head North Rim Bright Angel Vista Encantada Point Sublime 7770 ft Point 7459 ft Tiyo Point Widforss Point Visitor Center 8480ft Confucius Temple 2368m 7900 ft 2585 m 2274 m 7766 ft Grand Canyon Lodge 7081 ft Shiva Temple 2367 m 2403 m Obi Point Chuar Butte Buddha Temple 6394ft Colorado River 2159 m 7570 ft 7928 ft Cape Solitude Little 2308m 7204 ft 2417 m Francois Matthes Point WALHALLA PLATEAU 1949m HINDU 2196 m 8020 ft 6144ft 2445 m 1873m AMPHITHEATER N Cape Final Temple of Osiris YO Temple of Ra Isis Temple N 7916ft From 6637 ft CA Temple Butte 6078 ft 7014 ft L 2413 m Lake 1853 m 2023 m 2138 m Hillers Butte GE Walhalla Overlook 5308ft Powell T N Brahma Temple 7998ft Jupiter Temple 1618m ri 5885 ft A ni T 7851ft Thor Temple ty H 2438 m 7081ft GR 1794 m G 2302 m 6741 ft ANIT I 2158 m E C R Cape Royal PALISADES OF GO r B Zoroaster Temple 2055m RG e k 7865 ft E Tower of Set e ee 7129 ft Venus Temple THE DESERT To k r C 2398 m 6257ft Lake 6026 ft Cheops Pyramid l 2173 m N Pha e Freya Castle Espejo Butte g O 1907 m Mead 1837m 5399 ft nto n m A Y t 7299 ft 1646m C N reek gh Sumner Butte Wotans Throne 2225m Apollo Temple i A Br OTTOMAN 5156 ft C 7633 ft 1572 m AMPHITHEATER 2327 m 2546 ft R E Cocopa Point 768 m T Angels Vishnu Temple Comanche Point M S Co TONTO PLATFOR 6800 ft Phantom Ranch Gate 7829 ft 7073ft lor 2073 m A ado O 2386 m 2156m R Yuma Point Riv Hopi ek er O e 6646 ft Z r Pima Mohave Point Maricopa C Krishna Shrine T -

Contrasting Proterozoic Basement Complexes Near the Truncated Margin of Laurentia, Northwestern Sonora–Arizona International Border Region

spe393-04 page 123 Geological Society of America Special Paper 393 2005 Contrasting Proterozoic basement complexes near the truncated margin of Laurentia, northwestern Sonora–Arizona international border region Jonathan A. Nourse* Department of Geological Sciences, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, California 91768, USA Wayne R. Premo United States Geological Survey, Denver Federal Center, Denver, Colorado 80225, USA Alexander Iriondo Centro de Geosciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Campus Juriqilla, Querétaro 76230, Mexico Erin R. Stahl 164 El Camino Way, Claremont, California 91711, USA ABSTRACT We utilize new geological mapping, conventional isotope dilution–thermal ion- ization mass spectrometry (ID-TIMS) and sensitive high-resolution ion microprobe (SHRIMP) U-Pb zircon analyses, and whole-rock radiogenic isotope characteristics to distinguish two contrasting Proterozoic basement complexes in the international border region southeast of Yuma, Arizona. Strategically located near the truncated southwest margin of Laurentia, these Proterozoic exposures are separated by a north- west-striking Late Cretaceous batholith. Although both complexes contain strongly deformed Paleoproterozoic granitoids (augen gneisses) intruded into fi ne-grained host rocks, our work demonstrates marked differences in age, host rock composition, and structure between the two areas. The Western Complex reveals a >5-km-thick tilted section of fi nely banded felsic, intermediate, and mafi c orthogneiss interspersed with tabular intrusive bodies of medium-grained leucocratic biotite granite (1696 ± 11 Ma; deepest level), medium- grained hornblende-biotite granodiorite (1722 ± 12 Ma), and coarse-grained porphy- ritic biotite granite (1725 ± 19 Ma; shallowest level). Penetrative ductile deformation has converted the granites to augen gneisses and caused isoclinal folding and trans- position of primary contacts. -

Otis R. Marston Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf438n99sg No online items Otis R. Marston Papers: Finding Aid Processed by The Huntington Library staff. The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2015 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Otis R. Marston Papers: Finding mssMarston papers 1 Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Otis R. Marston Papers Dates (inclusive): 1870-1978 Collection Number: mssMarston papers Creator: Marston, Otis R. Extent: 432 boxes54 microfilm251 volumes162 motion picture reels61 photo boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: Professional and personal papers of river-runner and historian and river historian Otis R. Marston (1894-1979) and his collection of the materials on the history of Colorado River and Green River regions. Included are log books from river expeditions, journals, diaries, extensive original correspondence as well as copies of material in other repositories, manuscripts, motion pictures, still images, research notes, and printed material. Language: English. Access Collection is open to researchers with a serious interest in the subject matter of the collection by prior application through the Reader Services Department. Unlike other collections in the Huntington, an advanced degree is not a prerequisite for access The collection is open to qualified researchers. For more information, please visit the Huntington's website: www.huntington.org. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

Kopk, -A- 3>T 3D

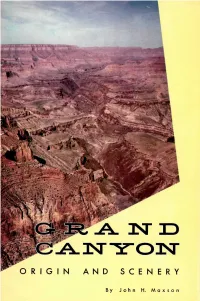

KOpK, -A- 3>T 3D ORIGIN AND SCENERY By John H. Maxson GRAND CANYON ORIGIN and SCENERY IK- JOHN H. MAXSON, Ph. D. Fellow, Geological Society of America; Collab orator, Grand Canyon National Park; Formerly, Asst. Professor of Geology, California Institute of Technology and Research Associate, Carnegie Institution of Washington, D. C. Copyright 1961 by GRAND CANYON NATURAL HISTORY' ASSOCIATION Illustrations by the Author COVER ILLUSTRATION: THE GRAND CANYON - VIEW WESTWARD FROM LIPAN POINT PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY NORTHLAND PRESS FLAGSTAFF, ARIZONA Bulletin No. 13 This booklet is one of a series published by the Grand Canyon Natural History Association to further visitor understanding and enjoyment of the scenic, scientif ic and historic values of Grand Canyon National Park. The Association cooperates with the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior and is recognized as an essential operating organization. It is primarily sponsored and operated by the Interpretation Division in Grand Canyon Na tional Park. Merrill D. Beal, Executive Secretary Grand Canyon Natural History Association Box 219, Grand Canyon, Arizona PUBLISHED IN COOPERATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 Geographic Setting 2 Geologic Setting 7 Sequence of Development 8 Stage 1. The Ancestral Colorado Plain .... 8 Stage 2. Regional Uplift Initiates New Cycle of Erosion — The Ancestral Canyon . 9 Stage 3. Erosion of the Outer Canyon .... 13 Stage 4. Enlargement of Outer Canyon and Cutting of Inner Gorge 27 Conclusion 31 INTRODUCTION The great canyon cut by the Colorado River across north ern Arizona for a distance of more than 200 miles is one of the earth's most impressive sights. -

Ancient Egyptian Treasures in the Grand Canyon

Subj: EGYPT/GRAND CANYON Date: 12/1/00 4:49:48 PM Pacific Standard Time From: [email protected] (McEwen) To: [email protected] -------------------- ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TREASURES IN THE GRAND CANYON Suppressed Archeological Information and Metaphysical Paradox ? Barry McEwen [email protected] Phoenix, Arizona November 30, 2000 On April 5th, 1909, there appeared a front page story in the Arizona Gazette. It told of an archeological expedition in the heart of the Grand Canyon funded by the Smithsonian Institute. (a full transcription of the article can be found at: http://www.keelynet.com/unclass/canyon.txt) It is a rich story of finding a labyrinth of man-made tunnel systems high above the Colorado River, a virtual citadel filled with ancient artifacts, hieroglyphs, armor, statues of deities and even mummies. Anyone contacting the Smithsonian Institute will receive a polite "no records found" reply to an inquiry about their supposed role in the Grand Canyon. The following narration shows how I came to be convinced of an exact location in the Grand Canyon that is a key to this story (regardless of whether the newspaper article is a hoax or not), and contains mathematical proof. This story also reveals an ancient cartographic code that led me to this conclusion, and the meaningful coincidences that unfolded as I pursued this mystery. The location is known as "Isis Temple" and is paramount in a well kept secret that is just now being uncovered in ways far richer and more important than material wealth. The cherished gem of Arizona, the Grand Canyon, one of the seven natural wonders of the world, contains a legacy and a link to a history known only by a few; suppressed not only by greed and politics, but by a forgotten code hidden right beneath our very feet. -

Mile Bank Camps ~ Attractions ~ Rapids Brown Is Park Service

Mile Bank Camps ~ Attractions ~ Rapids Brown is Park Service ~ SR is Sunrise ~ SS is Sunset Prior Trips -13.8 R Ropes Trail Camp Petroglyphs just upriver up Ropes Trail -11.0 L Ferry Swale Camp Petroglyphs -10.5 R Faatz Inscription Scout Left - Hole right of tongue -8.5 R Maybe Camp -7.5 L Finger Rock Camp -6.5 R Hidden Slough Camps -4.0 L Arch Just past Water Holes Canyon Behind restroom, 100 yards thru wash to petrified log, up slope to left (creek right) small old 0.0 R Lee's Ferry Lunch ~ '10 Pueblo dwelling at top. SR 06:30 ~ SS 5:30 0.8 R&L Paria confluence to Navajo Bridge Not potable water, No camping mile .8 to mile 4.5 both sides 4.5 Navajo Bridge 5.0 R 5 Mile (S) Very Small camp 5.9 R 6 Mile Wash (S) Downstream end of debris fan Nite 1 ~ '12 8.0 Badger Creek Rapid (5) Scout Left Lunch ~ '06 8.0 L Jackass Creek 2 Mile hike up pour -overs (use rope) to rim & Navajo Nation 8.1 L Jackass Camp (L) At foot of Badger Rapid, loud, share with hikers 8.1 R Badger Camp (M) Foot of Badger Rapid, hard pull in, share with hikers, rapid noise, driftwood 8.8 L Below Jackass (8.5 Mile) (S) Low water sandbar camp NO CAMP THERE IN 2012 9.0 L Sandbar (S) 10.2 10 Mile Rock Coconino Sandstone Nite 1 ~ '10 11.3 R Soap Creek Camp (M) Above the debris fan at Soap Creek Rapid, Boats will be beached in am, Condors Nite 1 ~ '06 11.4 Soap Creek Rapid (5) Scout Right on limestone block 12.0 Brown's Riffle (0) 12.1 L Salt Water Wash Camp (Browns) (S) Or Brown's Inscription Camp, small at top of eddy 12.1 L Brown's Inscription Near top of eddy, close to top of Supai ledges, 20 ft above the 10,000 cfs waterline 12.4 L 12.4 Mile (Below Salt Wash) (S) Behind debris from small side canyon. -

Welcome to the Grand Canyon Where History, Nature and the Most Beautiful Vistas in North America Can Be Found Right Outside Your

To Salt Lake City ZION To Bryce Canyon N.P. 0 50 Kilometers NATIONAL 17 PARK GLEN CANYON 0 50 Miles 18 NATIONAL 9 North RECREATION AREA H St. George 9 Lake A T 89 A 59 Powell U Kanab UTAH AD 93 V KAIBAB-PAIUTE ARIZONA A Fredonia Welcome to the Grand Canyon where history, nature and the most NE RESERVATION Page 389 Marble Canyon PIPE SPRING 168 15 NATIONAL MONUMENT Road closed 89 beautiful vistas in North America can be found right outside your Jacob Lake 98 ARIZON in winter ALT Unpaved roads 89 GRAND CANYON r door. Trails, overlooks and historical architecture mean you are never 169 are impassable e v when wet i NATIONAL PARK R To at a loss for something to do. The shuttle can take you easily from KAIBAB NATIONAL o Ton opah 169 d GRAND CANYON– FOREST a r o PARASHANT l 67 o NAVAJO INDIAN destination to destination along the South Rim. Grand Canyon Village Las NATIONAL C 95 RESERVATION Lake MONUMENT Tuweep North Vegas Mead er Rim offers beauty, history and practicality hosting lovely hotels, stores and Pearce Ferry R iv do Henderson ra Desert lo 160 museums. Whether you come for a few hours or a few days, you will C o Grand Canyon View LAKE MEAD Village Boulder NATIONAL 64 want to plan carefully. RECREATION Meadview HAVASUPAI Tusayan City AREA Cameron To INDIAN 180 RESERVATION Barstow 89 HUALAPAI INDIAN 64 Visit GrandCanyonTourist.com for a complete guide to planning your Lake RESERVATION Mohave Valle WUPATKI 180 NATIONAL N Grand Canyon vacation. -

Thomas Moran, William Robinson Leigh, and Fernand H

Romance and realism--the Grand Canyon painters between 1874-1920: Thomas Moran, William Robinson Leigh, and Fernand H. Lungren Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Neal, Saralie E. Martin, 1922- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 04:39:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/566593 ROMANCE AND REALISM—THE GRAND CANYON PAINTERS BETWEEN 1874-1920: THOMAS MORAN, WILLIAM ROBINSON LEIGH, AND FERNAND H. LUNGREN by Saralie E. Martin Neal A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ART In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 7 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under the rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major depart ment or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed used of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

Lost Cave City in the Grand Canyon?

Lost Cave City in the Grand Canyon? http://www.crystalinks.com/gc_egyptconnection.html Did an ancient civilization live in caves below the Grand Canyon? This is as vague a statement as wondering why some of the ancient Mesoamerican people depicted their gods as white men or the Olmec gods looked African. Stretching the imagination ... perhaps whatever was found in the Grand Canyon caves discussed below, is linked to Ancient Alien Theory. It is interesting to speculate on ancient Egyptians or Tibetans flying to the Grand Canyon in Vimanas, but, to date, there is no tangible proof to support these claims. Archeological Coverups by David Hatcher Childress Perhaps the most amazing suppression of all is the excavation of an Egyptian tomb by the Smithsonian itself in Arizona. A lengthy front page story of the Phoenix Gazette on April 5, 1909, gave a highly detailed report of the discovery and excavation of a rock-cut vault by an expedition led by a Professor S.A. Jordan of the Smithsonian. The Smithsonian, however, claims to have absolutely no knowledge of the discovery or its discoverers. Front page of The Phoenix Gazette of April 5th, 1909 The World Explorers Club decided to check on this story by calling the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., though we felt there was little chance of getting any real information. After speaking briefly to an operator, we were transferred to a Smithsonian staff archaeologist, and a woman's voice came on the phone and identified herself. I told her that I was investigating a story from a 1909 Phoenix newspaper article about the Smithsonian Institution's having excavated rock-cut vaults in the Grand Canyon where Egyptian artifacts had been discovered, and whether the Smithsonian Institution could give me any more information on the subject. -

National Transportation Safety Board

PB87-9 1.0403 b NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594 AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT REPORT GRAND CANYON AIRLINES, INC., AND HELITECH, INC., MIDAIR COLLISION OVER GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK JUNE 18, 1986 NTSBIAAR-87103 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT r . n T'ECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE r. Report NO. 2.Government Accession No, 3.Recipient's Catalog No. NTSB/AAR-87/03 PB87-910403 1. Title and Subtitle Aircraft Accident Report-Grand u.Report Date Canyon Airlines, Inc., and Helitech, Inc., Midair July 24, 1987 Collision Over Grand Canyon National Park, June 18, 1986 6.Performing Organization Code I. Author(s) 8.Performing Organization Report No. 1. Performing Organization Name and Address lO.Work Unit No. 4426B National Transportation Safety Board ll.Contract or Grant No. Bureau of Accident Investigation Washington, D.C. 20594 13.Type of Report and Period Covered l2.Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Aircraft Accident Report June 18, 1986 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Washington, D. C. 20594 14.Sponsoring Agency Code lS.Supplementary Notes 16.Abstract On June 18, 1986, at 0855 mountain standard time a Grand Canyon Airlines DHC-6, N76GC (Twin Otter), call sign Canyon 6, took off from runway 21 of the Grand Canyon Airport. The flight, a scheduled air tour over Grand Canyon National Park, was to be about 50 minutes in duration. Shortly thereafter, at 0913, a Helitech Bell 206B (Jet Ranger), NGTC, call sign Tech 2, began its approximate 30-minute, on-demand air tour of the Grand Canyon. It took off from its base at a heliport adjacent to State route 64 in Tusayan, Arizona, located about 5 miles south of the main entrance to the south rim of the park. -

A Gathering of Grand Canyon Historians

AA GatherGatheringing ofof GrGrandand CanCanyyonon HistorHistoriansians Ideas, Arguments, and First-Person Accounts Proceedings of the Inaugural Grand Canyon History Symposium, January 2002 Compiled and Edited by Michael F. Anderson Grand Canyon Association PO Box 399 Grand Canyon, AZ 86023-0399 (800) 858-2808 www.grandcanyon.org Copyright © 2005 by the Grand Canyon Association All rights reserved. Published 2005 No portion of this book (with the exception of short quotations for the purpose of review) may be reproduced, in whole or in part, by any means, without the written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Edited by Todd R. Berger Designed by Rudy Ramos 10 09 08 07 06 05 1 2 3 4 5 6 ISBN: 0-938216-83-X Monograph Number 13 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grand Canyon History Symposium (1st : 2002) A gathering of Grand Canyon historians : ideas, arguments, and first-person accounts : proceedings of the inaugural Grand Canyon History Symposium, January 2002 / compiled and edited by Michael F. Anderson.— 1st ed. p. cm. — (Monograph / Grand Canyon Association ; no. 13) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-938216-83-X 1. Grand Canyon (Ariz.)—History—Congresses. 2. Grand Canyon National Park (Ariz.)—History—Congresses. I. Anderson, Michael F. II. Title. III. Series: Monograph (Grand Canyon Association) ; no. 13. F788.G7465 2002 979.1’32—dc22 2005015968 Cover background photograph courtesy Emery Kolb Collection, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff (NAU.PH.568.2816). -

Steve Grossman (Moderator (SG); Chuck Graf (CG) and Dave Ganci

Transcription: Grand Canyon Historical Society Oral History Presenter(s): Tom Martin (TM); Steve Grossman (moderator (SG); Chuck Graf (CG) and Dave Ganci (DG) with Glenn Rink (GR); Alan Doty (AD); Bob Packard (BP); Sean Peters (SP); Bruce Grubbs (BG) and Chauncey Parker (CP); George Bain (GB); Stan Mish (SM) and Bill Hatcher (BH) Subject: Granitica – Rock climbing in Grand Canyon Date of Presentation: March 5, 2016 Afternoon Session Transcriber: Dannie Derryberry Date of Transcription: February 2019 Transcription Reviewer: Sue Priest, Tom Martin Keys: Grand Canyon Climbing History (TM): Today is March 5, 2016. We are at the Museum of Northern Arizona at the first ever Grand Canyon Granitica with Steve Grossman. This is the afternoon session of the first day, Saturday. Steve Grossman introduces Chuck Graf (CG) and Dave Ganci (DG) presentation. Glenn Rink (GR) also speaks (14:37) All right everybody, back for the second half of day one here. Next presentation’s gonna be on Angel’s Gate which is a quadruple summited formation. The first pair of people to come up and talk about this is gonna be Dave Ganci again and… Audience comment: Oh, no! (laughter) …Chuck Graf. Chuck Graf’s lifetime love of the Grand Canyon began in 1965 when his Coronado High School, which is in Scottsdale, geology teacher led an overnight Kaibab to Bright Angel backpack trip, camping at Burro Springs. He immediately caught the Canyon Virus, which started a long succession of Canyon backpack trips and a smattering of river trips over nearly every major holiday during his university years and beyond.