Notes on the Context of Ada Cambridge's the Perversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reluctant Lawyer, Reluctant Politician

Alfred Deakin (1856–1919) Australia’s 2nd Prime Minister Terms of office 24 September 1903 to 27 April 1904 • 5 July 1905 to 13 November 1908 • 2 June 1909 to 29 April 1910 Reluctant lawyer, reluctant politician Deakin first met David Syme, the Scottish-born owner of The Age newspaper, in May 1878, as the result of their mutual interest in spiritualism. Soon after, Syme hired the reluctant lawyer on a trial basis, and he made an immediate impression. Despite repeatedly emphasising how ‘laborious’ journalism could be, Deakin was good at it, able to churn out leaders, editorials, investigative articles and reviews as the occasion demanded. Syme wielded enormous clout, able to make and break governments in colonial Victoria and, after 1901, national governments. A staunch advocate of protection for local industry, he ‘connived’ at Deakin’s political education, converting his favourite young journalist, a free-trader, into a protectionist. As Deakin later acknowledged, ‘I crossed the fiscal Rubicon’, providing a first clear indication of his capacity for political pragmatism--his willingness to reshape his beliefs and ‘liberal’ principles if and when the circumstances required it. Radical MLA David Gaunson dismissed him as nothing more than a ‘puppet’, ‘the poodle dog of a newspaper proprietor’. Syme was the catalyst for the start of Deakin’s political career in 1879-80. After two interesting false starts, Deakin was finally elected in July 1880, during the same year that a clairvoyant predicted he would soon embark on a life-changing journey to London to participate in a ‘grand tribunal’. Deakin did not forget what he described as ‘extraordinary information’, and in 1887 he represented Victoria at the Colonial Conference in London. -

Ned Kelly and the Myth of a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria

Ned Kelly and the Myth of a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria Stuart E. Dawson Department of History, Monash University Ned Kelly and the Myth of a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria Dr. Stuart E. Dawson Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Published by Dr. Stuart E. Dawson, Adjunct Research Fellow, Department of History, School of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, 3800. Published June 2018. ISBN registered to Primedia E-launch LLC, Dallas TX, USA. Copyright © Stuart Dawson 2018. The moral right of the author has been asserted. Author contact: [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-64316-500-4 Keywords: Australian History Kelly, Ned, 1855-1880 Kelly Gang Republic of North-Eastern Victoria Bushrangers - Australia This book is an open peer-reviewed publication. Reviewers are acknowledged in the Preface. Inaugural document download host: www.ironicon.com.au Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs This book is a free, open-access publication, and is published under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs licence. Users including libraries and schools may make the work available for free distribution, circulation and copying, including re-sharing, without restriction, but the work cannot be changed in any way or resold commercially. All users may share the work by printed copies and/or directly by email, and/or hosting it on a website, server or other system, provided no cost whatsoever is charged. Just print and bind your PDF copy at a local print shop! (Spiral-bound copies with clear covers are available in Australia only by print-on-demand for $199.00 per copy, including registered post. -

December 2019 – 3Rd January 2020: End of Year Closure

PATRON: The Hon Linda Dessau AC PRESIDENT: Mr David Zerman Governor of Victoria December Events: 12th December: Climate Extremes: Present and Future With Professor Andy Pitman AO The RSV Research Medal Lecture & End of Year Dinner 25th December 2019 – 3rd January 2020: End of Year Closure February 2020 Advance Notice: 13th February: The State Control Centre: Forecasting Victoria’s Extreme Weather 27th February: Diamonds: an Implant’s Best Friend December 2019 Newsletter Print Post Approved 100009741 The Royal Society of Victoria Inc. 8 La Trobe Street, Melbourne Victoria 3000 Tel. (03) 9663 5259 rsv.org.au December Events Climate Extremes: Present and Future Thursday, 12th December from 6:30pm Climate extremes are events such as heatwaves, extreme rainfall, cyclones and drought that affect humans, our natural environment and multiple socio-economic systems. The evidence is now unambiguous that some climate extremes are responding to increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, yet how some other extremes are responding is proving more complex. Join Professor Andy Pitman to explore the evidence for how and why climate extremes are changing, and what we can anticipate about how they will change in the future. The limits to our current capability and how climate science is trying to address those limits via new approaches to modelling will be discussed. About the speaker: Professor Andy Pitman AO is a Professor in climate science at the University of New South Wales. He is the Director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes (CLEx), which brings together five Australian universities (including Monash University and the University of Melbourne) and a suite of international partner organisations to understand the behaviour of climate extremes and how they directly affect Australian natural and economic systems. -

Reap the Benefits of the Successful Striv¬

* i i i Foreword [ HIS BOOKLET, describing the growth and development of the T country districts of Victoria, laimamiamiait » « t t i M t i purpose. > » * has . • • • a double It is •4 * * m B* V * •«•liMWM ‘ designed to tell the story— of necessity briefly—of one of the eight great districts into which Vic¬ toria is divided. It is also designed to remind a new generation of the great and dominant part played in this story by UThe Age” throughout the 75 years of its far-sighted influence on public life. The pressure of to-day sometimes causes us to forget the debt due to yesterday. We i reap the benefits of the successful striv¬ ing and initiative of a great organ of public opinion, but forget the principles of policy upon which that striving and initiative are grounded. The supreme service rendered by “The Age” is comprehended in the twin policies of “Unlocking the Lands for the People and “Protection.” Each arose out of the 1 historic necessities of the State after the Gold Rush had ended. But each was based upon a reasoned conception of State¬ craft which aimed at a State consisting of hundreds of thousands of families working on farms and in factories, masters of their i own home market, owning on easy terms their own freeholds, protected by a tariff from the unfair competition of oversea competitors, and possessing such a wide franchise, and so many representative in¬ stitutions, as to be really a Free Democ¬ racy within the British Empire. The fight for these policies of “The Age” was long and sometimes bitter, but in the result splendidly successful. -

The Making of Australian Federation: an Analysis of the Australasian Convention Debates, 1891, 1897-1898

The Making of Australian Federation: An Analysis of The Australasian Convention Debates, 1891, 1897-1898 By Eli Kem Senior Seminar: Hst 499 Professor Bau-Hwa Hsieh June 15, 2007 Readers Professor Narasignha Sil Professor David Doellinger Copyright Eli Kem 2007 I The English constitution played a pivotal role in the shaping of the Australian constitution. This paper seeks to demonstrate the validity of this claim through an analysis of the debates in the Australian colonies of 1891-1898 and through emphasizing inter alia the role payed by one of the delegates Alfred Deakin. The 1890 Australasian Conference, held in Melbourne, had been instigated by a conference in England in 1887 where all the colonies of Britain met. The 1890 conference represented the British colonies in the region of Southeast Asia. Seven delegates from each of the seven colonies in the region met, and forced the question of unification of the colonies. Independence from Britain was not on their mind, only uniting to have one common voice and an equal stake within the Commonwealth of the United Kingdom. At the conference, the delegates initiated a discussion for the path to unification that would continue until 1901. The colonies had written a constitution in 1891, and debates took place in 1891, 1897, and 1898 with the lapse in debate due to an economic depression. By 1901 the colonies had agreed on a constitution and it was ratified by an act of Parliament in Britain, which allowed the five colonies on Australia and Tasmania to unify. Essentially, the debate centered on the distribution and balance of power among the states. -

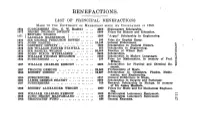

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE to the UNIVERSITY Oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION in 1853

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. .. £866 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Prizes for History and Education. 1871 j LA^HL^MACKmNON I 100° "ArSUS" S«h°lar8hiP ln Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 666 Scholarship in Engineering. 1876 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 6000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS 160 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,887 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics, and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 6217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 8900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship In Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT 1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. BENEFACTIONS (Continued). 1908 TEACHING STAFF £1160 General Expenses. oo including Professor Sponcer £2riS Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1908 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1908 GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2600 Books. 1004 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarship!!. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND . -

Recorder No. 101 August 1979

> Recorder C3 n /MELBOURNE BRANCH AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF LABOUR HISTORY CT Re/3:istered for Posting; as a Periodical - Cate/3:ory B Price 10 cents Nunber 101 Editorial Aumist 1979 Tile next meeting of the Melbourne Branch will be held at the offices of the Australian Insurance Employees' Union at 105 Queen Street, Melbourne, 3000, on Tuesday 28 August at 7»45 p.n. The speaker will be Lloyd Edmonds who will talk about the Anti-Communist Referendum and the Communist Party Underground, Readers will remember that Lloyd has spoken to us before on the subject of his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, We look forward to another of his interesting talks, Bip: Red Book Fair The Big Red Book Pair, held at the Collingwood Town Hall on Saturday 14 July was a very successful occasion for all concerned. The organisers were pleased with the attendance and the $3,000 raised. With the exception of two rather excited and pugulistic book dealers, most of the buyers were pleased with the range of books available althoiigh the prices of some volmes designated 'rare' were rather high. However, as far as the Labour History Society was concerned, the Pair was very successful, A member of o\ir Canberra Executive, Eric Fry, came down to lead a seminar on the writing of labour history. It was a particularly well-attended seminar with about 50 people present, Eric's talk in opening discussion on the subject was very well received and encouraged many of those present to 'offer their opinions on how labour history might be written and to whom it might be directed. -

Six Problems in the Biography of Alfred Deakin

Six Problems in the Biography of Alfred Deakin William Coleman1 Judith Brett’s The Enigmatic Mr Deakin constitutes the fifth biographical study of Alfred Deakin. It succeeds the admiring salute of Murdoch (1999 [1923]), the inscriptional chronicle of La Nauze (1965), the revelatory exposé of Gabay (1992) and the waggish sallies of Rickard (1996). We now have Brett’s full-length portrait of the man, in all his parts (Brett, 2017). But the topic of Alfred Deakin will not be exhausted by even this attention. Let me nominate six problems that remain for future biographers to puzzle over. 1. Deakin’s spiritualism Deakin was a committed spiritualist. Contemporary observers—you and me—are baffled by how Deakin could so readily soak up such twaddle. His biographers have sought to reconcile his spiritualism into our own understanding by means of two strategies. Both are ‘apologetic’ in some measure. 1. Minimisation. Murdoch and La Nauze present Deakin’s spiritualism as a youthful jeu d’esprit. This contention, however, became untenable with the remarkable disclosures of Gabay. And Brett has reinforced Gabay with further details of how much Deakin’s spiritualist activities extended into his maturity. As late as 1891—the same year he was a delegate at the Federation Convention— Deakin was seeking guidance from the séances of the dubious Mrs Cohen. 2. Rationalisation in terms of rationality. Gabay and Brett are inclined to present spiritualism as a wayward progeny of the conquering rationalism of Deakin’s 1 College of Business and Economics, The Australian National University, [email protected]. -

A Special Connection: Georgina Sweet and The

A special connection Georgina Sweet and the Tiegs Zoology Museum Karla Way and David Young As you cast your eye over an object on display in one of the cultural collections at the University of Melbourne, you may not be aware of its history. Naturally, all these items have a story, which in some cases may be even more interesting than the object itself. A good example is provided by specimens that Dr Georgina Sweet donated to the Tiegs Zoology Museum early in the twentieth century. This museum was set up by Professor Walter Baldwin Spencer (1860–1929) soon after his appointment to the new professorship of biology in 1887. The collection was intended primarily for teaching purposes and consists of zoological specimens from around Australia and overseas. In 1958–59 it was named Georgina enrolled in biology as her time as an undergraduate. As in honour of Professor Oscar Werner an undergraduate at the University it happens, the official catalogue of Tiegs, chair of zoology from 1948 of Melbourne in 1892, and so the collection was started at that until his death in 1956.1 would have studied under Baldwin time, entitled Register of specimens in Georgina Sweet (1875–1946) Spencer. She received her Bachelor the museum of the Biological School, showed an early interest in science, of Science degree in 1896 and University of Melbourne. The first encouraged by her father, George continued with postgraduate studies, few entries acknowledge donations Sweet, who was the manager of the receiving her master’s degree in from overseas and are clearly dated Brunswick Brick and Tile Works and 1898 and a doctorate in 1904. -

BENEFACTIONS. Te

to BENEFACTIONS. te LIST OF PRIiNCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADB TO THE UNIVERSITY ur MKMIOUUNB SINCK ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec. G. W. Rusden) £856 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Frizes for History and Education. 1871 1 EDWARD WILSON - I 1000 Argus Scholarship in Engineering. ( LACHLAN MACKINNON > ' 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE - 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 655 Scholarship in Engineering, 1875 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 5000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS .... 150 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT - 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND .... 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,837 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 5217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY - - 3900 Scholarships in .Surgery and1 Pathology, 1894 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarships. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 750 Research Scholarship in Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. SJiNKFJ C'JTOXS tConlinual). 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT £1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT - 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND - 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND .... 466 General Expenses. 1903 TEACHING STAFF 1160 General Expenses. including Professor Spencer £258 Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1903 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1903 GEORGE McARTHUR - Library of 2,500 Books. -

A Father of Federation, a Family Man Australia's 2Nd Prime Minister

Alfred Deakin (1856–1919) Australia’s 2nd Prime Minister Terms of office 24 September 1903 to 27 April 1904 • 5 July 1905 to 13 November 1908 • 2 June 1909 to 29 April 1910 A father of federation, a family man When a no-confidence vote terminated Deakin’s conservative coalition government in October 1890, amid allegations of corruption and culpable excess, he was forced to reinvent himself. It was not easy. His diaries indicate just how deeply troubled he was by the circumstances of his political fall from grace, his dire financial predicament, spiritual unease and a lack of confidence in his community’s desire to achieve social progress through just legislation. Historian Stuart Macintyre suggests that Deakin’s occupation of the Victorian parliamentary backbench for the duration of the 1890s was probably ‘an act of penance for his earlier profligacy’. To make matters worse, at the beginning of the decade the relative tranquillity of domestic life collapsed when all family members had to withstand a ‘horrid misunderstanding’ between the two most important women in Deakin’s life, his wife Pattie and sister Kate. Conflict had been simmering for years because of Pattie’s belief, probably valid, that her spinster sister-in-law had been accorded too large a role in the raising of the Deakin children—of whom, by Christmas Day 1891, there were three daughters (Ivy, Stella and the yuletide baby Vera). The tension endured. Confronted by this turmoil in both his public and private lives, somehow Deakin managed to give shape to the crucial role he would play in the achievement of Australian nationhood. -

Understanding Victoria

Introduction: Introduction: Understanding Victoria Understanding Victoria Old Colonists’ Association of Ballarat Old Colonists’ Association of Ballarat Presented by Gary Morgan Presented by Gary Morgan June 26, 2011 June 26, 2011 I am pleased to be addressing the Old I am pleased to be addressing the Colonists’ Association of Ballarat Old Colonists’ Association of at the Old Colonists Club. It s Ballarat at the Old Colonists Club. more than seven years snce I gave It s more than seven years snce the naugural Dr J H Pryor Memoral I gave the naugural Dr J H Pryor Lecture at the Ballaarat Club on Memoral Lecture at the Ballaarat May 22, 2004. I must be the first Club on May 22, 2004. I must be the person who will have addressed ‘both first person who will have addressed sdes’ of the Eureka Stockade! ‘both sdes’ of the Eureka Stockade! Understanding Victoria - where t Understanding Victoria - where t came from, and what made t what came from, and what made t what Left to Right: Andrew Robson, Councillor - Gary Morgan Left to Right: Andrew Robson, Councillor - Gary Morgan - Mchael Blenkron, Presdent t s today s a fascnatng study. - Mchael Blenkron, Presdent t s today s a fascnatng study. It It s not just a seres of successve s not just a seres of successve Governments or business leaders, or any one thing or person. Governments or business leaders, or any one thing or person. It is an amazing series of events and people that have come together at It is an amazing series of events and people that have come together at varous tmes snce 1835 under ncredble crcumstances.