Chapter Eight Rethinking 'Red-Ribbon' Protest: Bendigo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reluctant Lawyer, Reluctant Politician

Alfred Deakin (1856–1919) Australia’s 2nd Prime Minister Terms of office 24 September 1903 to 27 April 1904 • 5 July 1905 to 13 November 1908 • 2 June 1909 to 29 April 1910 Reluctant lawyer, reluctant politician Deakin first met David Syme, the Scottish-born owner of The Age newspaper, in May 1878, as the result of their mutual interest in spiritualism. Soon after, Syme hired the reluctant lawyer on a trial basis, and he made an immediate impression. Despite repeatedly emphasising how ‘laborious’ journalism could be, Deakin was good at it, able to churn out leaders, editorials, investigative articles and reviews as the occasion demanded. Syme wielded enormous clout, able to make and break governments in colonial Victoria and, after 1901, national governments. A staunch advocate of protection for local industry, he ‘connived’ at Deakin’s political education, converting his favourite young journalist, a free-trader, into a protectionist. As Deakin later acknowledged, ‘I crossed the fiscal Rubicon’, providing a first clear indication of his capacity for political pragmatism--his willingness to reshape his beliefs and ‘liberal’ principles if and when the circumstances required it. Radical MLA David Gaunson dismissed him as nothing more than a ‘puppet’, ‘the poodle dog of a newspaper proprietor’. Syme was the catalyst for the start of Deakin’s political career in 1879-80. After two interesting false starts, Deakin was finally elected in July 1880, during the same year that a clairvoyant predicted he would soon embark on a life-changing journey to London to participate in a ‘grand tribunal’. Deakin did not forget what he described as ‘extraordinary information’, and in 1887 he represented Victoria at the Colonial Conference in London. -

CHAPTER VI1 DURING the Night of March 25Th, on Which the Pickets Of

CHAPTER VI1 BEFORE AMIENS DURINGthe night of March 25th, on which the pickets of rhe 4th Australian Division were, not without a grim eagerness, waiting for the Germans on the roads south-west of Arras, the 3rd Division had been entraining near St. Omer in Flanders to assemble next to the 4th. Some of its trains were intended to stop at Doullens on the main line of road and rail, due east of Arras, and twenty-one miles north of Amiens, and the troops to march thence towards Arras; other trains were, to be switched at Doullens to the Arras branch line, and to empty their troops at Mondicourt-Pas, where they would be billetted immediately south-west of the 4th Division. The eight trains allotted for the division were due to leave from 9.10 p.m. onwards at three hours’ intervals during the night and the next day; but, after the first trains had departed, carrying head- quarters of the 10th and 11th Brigades and some advanced units, there was delay in the arrival oi those for the rest of the division. The waiting battalions lay down at the roadside in the bitter cold; some companies were stowed into barns. During the morning of the 26th the trains again began to appear regularly. On the journey to Doullens the troops saw first evidences of the great battle in the south-a number of men who had been in the fighting, and several red cross trains full of wounded. There was a most depressing atmosphere of hopelessness about them all (says the history of the 40th Battalion),l but we saw some New Zealanders who told us that their division had gone down, and that the 4th Australian Division was also on the way, so we bucked up considerably. -

Ned Kelly and the Myth of a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria

Ned Kelly and the Myth of a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria Stuart E. Dawson Department of History, Monash University Ned Kelly and the Myth of a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria Dr. Stuart E. Dawson Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Published by Dr. Stuart E. Dawson, Adjunct Research Fellow, Department of History, School of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, 3800. Published June 2018. ISBN registered to Primedia E-launch LLC, Dallas TX, USA. Copyright © Stuart Dawson 2018. The moral right of the author has been asserted. Author contact: [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-64316-500-4 Keywords: Australian History Kelly, Ned, 1855-1880 Kelly Gang Republic of North-Eastern Victoria Bushrangers - Australia This book is an open peer-reviewed publication. Reviewers are acknowledged in the Preface. Inaugural document download host: www.ironicon.com.au Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs This book is a free, open-access publication, and is published under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs licence. Users including libraries and schools may make the work available for free distribution, circulation and copying, including re-sharing, without restriction, but the work cannot be changed in any way or resold commercially. All users may share the work by printed copies and/or directly by email, and/or hosting it on a website, server or other system, provided no cost whatsoever is charged. Just print and bind your PDF copy at a local print shop! (Spiral-bound copies with clear covers are available in Australia only by print-on-demand for $199.00 per copy, including registered post. -

December 2019 – 3Rd January 2020: End of Year Closure

PATRON: The Hon Linda Dessau AC PRESIDENT: Mr David Zerman Governor of Victoria December Events: 12th December: Climate Extremes: Present and Future With Professor Andy Pitman AO The RSV Research Medal Lecture & End of Year Dinner 25th December 2019 – 3rd January 2020: End of Year Closure February 2020 Advance Notice: 13th February: The State Control Centre: Forecasting Victoria’s Extreme Weather 27th February: Diamonds: an Implant’s Best Friend December 2019 Newsletter Print Post Approved 100009741 The Royal Society of Victoria Inc. 8 La Trobe Street, Melbourne Victoria 3000 Tel. (03) 9663 5259 rsv.org.au December Events Climate Extremes: Present and Future Thursday, 12th December from 6:30pm Climate extremes are events such as heatwaves, extreme rainfall, cyclones and drought that affect humans, our natural environment and multiple socio-economic systems. The evidence is now unambiguous that some climate extremes are responding to increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, yet how some other extremes are responding is proving more complex. Join Professor Andy Pitman to explore the evidence for how and why climate extremes are changing, and what we can anticipate about how they will change in the future. The limits to our current capability and how climate science is trying to address those limits via new approaches to modelling will be discussed. About the speaker: Professor Andy Pitman AO is a Professor in climate science at the University of New South Wales. He is the Director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes (CLEx), which brings together five Australian universities (including Monash University and the University of Melbourne) and a suite of international partner organisations to understand the behaviour of climate extremes and how they directly affect Australian natural and economic systems. -

The Vocabulary of Australian English

THE VOCABULARY OF AUSTRALIAN ENGLISH Bruce Moore Australian National Dictionary Centre Australian National University The vocabulary of Australian English comes from many sources. This document outlines some of the most important sources of Australian words, and some of the important historical events that have shaped the creation of Australian words. At times, reference is made to the Australian Oxford Dictionary (OUP 1999) edited by Bruce Moore. 1. BORROWINGS FROM AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES ...2 2. ENGLISH FORMATIONS .....................................................................7 3. THE CONVICT ERA ...........................................................................11 4. BRITISH DIALECT .............................................................................15 5. BRITISH SLANG ................................................................................17 6. GOLD .................................................................................................18 7. WARS.................................................................................................21 © Australian National Dictionary Centre Page 1 of 24 1. BORROWINGS FROM AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES In 1770 Captain James Cook was forced to beach the Endeavour for repairs near present-day Cooktown, after the ship had been damaged on reefs. He and Joseph Banks collected a number of Aboriginal words from the local Guugu Yimidhirr people. One of these words was kangaroo, the Guugu Yimidhirr name for the large black or grey kangaroo Macropus -

Reap the Benefits of the Successful Striv¬

* i i i Foreword [ HIS BOOKLET, describing the growth and development of the T country districts of Victoria, laimamiamiait » « t t i M t i purpose. > » * has . • • • a double It is •4 * * m B* V * •«•liMWM ‘ designed to tell the story— of necessity briefly—of one of the eight great districts into which Vic¬ toria is divided. It is also designed to remind a new generation of the great and dominant part played in this story by UThe Age” throughout the 75 years of its far-sighted influence on public life. The pressure of to-day sometimes causes us to forget the debt due to yesterday. We i reap the benefits of the successful striv¬ ing and initiative of a great organ of public opinion, but forget the principles of policy upon which that striving and initiative are grounded. The supreme service rendered by “The Age” is comprehended in the twin policies of “Unlocking the Lands for the People and “Protection.” Each arose out of the 1 historic necessities of the State after the Gold Rush had ended. But each was based upon a reasoned conception of State¬ craft which aimed at a State consisting of hundreds of thousands of families working on farms and in factories, masters of their i own home market, owning on easy terms their own freeholds, protected by a tariff from the unfair competition of oversea competitors, and possessing such a wide franchise, and so many representative in¬ stitutions, as to be really a Free Democ¬ racy within the British Empire. The fight for these policies of “The Age” was long and sometimes bitter, but in the result splendidly successful. -

Australian Army Journal Is Published by Authority of the Chief of Army

Australian Army Winter edition 2014 Journal Volume XI, Number 1 • What Did We Learn from the War in Afghanistan? • Only the Strong Survive — CSS in the Disaggregated Battlespace • Raising a Female-centric Battalion: Do We Have the Nerve? • The Increasing Need for Cyber Forensic Awareness and Specialisation in Army • Reinvigorating Education in the Australian Army The Australian Army Journal is published by authority of the Chief of Army The Australian Army Journal is sponsored by Head Modernisation and Strategic Planning, Australian Army Headquarters © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This journal is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review (as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968), and with standard source credit included, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Contributors are urged to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in their articles; the Editorial Advisory Board accepts no responsibility for errors of fact. Permission to reprint Australian Army Journal articles will generally be given by the Editor after consultation with the author(s). Any reproduced articles must bear an acknowledgment of source. The views expressed in the Australian Army Journal are the contributors’ and not necessarily those of the Australian Army or the Department of Defence. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise for any statement made in this journal. ISSN 1448-2843 Editorial Advisory Board Prof Jeffrey Grey LTGEN Peter Leahy, AC (Retd) MAJGEN Elizabeth Cosson, AM (Retd) Dr John Blaxland BRIG Justin Kelly, AM (Retd) MAJGEN Michael Smith, AO (Retd) Dr Albert Palazzo Mrs Catherine McCullagh Dr Roger Lee RADM James Goldrick (Retd) Prof Michael Wesley AIRCDRE Anthony Forestier (Retd) Australian Army Journal Winter, Volume XI, No 1 CONTENTS CALL FOR PAPERS. -

The Making of Australian Federation: an Analysis of the Australasian Convention Debates, 1891, 1897-1898

The Making of Australian Federation: An Analysis of The Australasian Convention Debates, 1891, 1897-1898 By Eli Kem Senior Seminar: Hst 499 Professor Bau-Hwa Hsieh June 15, 2007 Readers Professor Narasignha Sil Professor David Doellinger Copyright Eli Kem 2007 I The English constitution played a pivotal role in the shaping of the Australian constitution. This paper seeks to demonstrate the validity of this claim through an analysis of the debates in the Australian colonies of 1891-1898 and through emphasizing inter alia the role payed by one of the delegates Alfred Deakin. The 1890 Australasian Conference, held in Melbourne, had been instigated by a conference in England in 1887 where all the colonies of Britain met. The 1890 conference represented the British colonies in the region of Southeast Asia. Seven delegates from each of the seven colonies in the region met, and forced the question of unification of the colonies. Independence from Britain was not on their mind, only uniting to have one common voice and an equal stake within the Commonwealth of the United Kingdom. At the conference, the delegates initiated a discussion for the path to unification that would continue until 1901. The colonies had written a constitution in 1891, and debates took place in 1891, 1897, and 1898 with the lapse in debate due to an economic depression. By 1901 the colonies had agreed on a constitution and it was ratified by an act of Parliament in Britain, which allowed the five colonies on Australia and Tasmania to unify. Essentially, the debate centered on the distribution and balance of power among the states. -

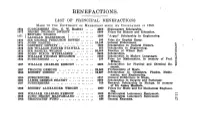

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE to the UNIVERSITY Oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION in 1853

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. .. £866 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Prizes for History and Education. 1871 j LA^HL^MACKmNON I 100° "ArSUS" S«h°lar8hiP ln Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 666 Scholarship in Engineering. 1876 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 6000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS 160 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,887 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics, and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 6217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 8900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship In Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT 1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. BENEFACTIONS (Continued). 1908 TEACHING STAFF £1160 General Expenses. oo including Professor Sponcer £2riS Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1908 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1908 GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2600 Books. 1004 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarship!!. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND . -

Does War Belong in Museums?

Wolfgang Muchitsch (ed.) Does War Belong in Museums? Volume 4 Editorial Das Museum, eine vor über zweihundert Jahren entstandene Institution, ist gegenwärtig ein weltweit expandierendes Erfolgsmodell. Gleichzeitig hat sich ein differenziertes Wissen vom Museum als Schlüsselphänomen der Moderne entwickelt, das sich aus unterschiedlichen Wissenschaftsdisziplinen und aus den Erfahrungen der Museumspraxis speist. Diesem Wissen ist die Edition gewidmet, die die Museumsakademie Joanneum – als Einrichtung eines der ältesten und größten Museen Europas, des Universalmuseum Joanneum in Graz – herausgibt. Die Reihe wird herausgegeben von Peter Pakesch, Wolfgang Muchitsch und Bettina Habsburg-Lothringen. Wolfgang Muchitsch (ed.) Does War Belong in Museums? The Representation of Violence in Exhibitions An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative ini- tiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 (BY-NC-ND). which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Natio- nalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or uti- lized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Recorder No. 101 August 1979

> Recorder C3 n /MELBOURNE BRANCH AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF LABOUR HISTORY CT Re/3:istered for Posting; as a Periodical - Cate/3:ory B Price 10 cents Nunber 101 Editorial Aumist 1979 Tile next meeting of the Melbourne Branch will be held at the offices of the Australian Insurance Employees' Union at 105 Queen Street, Melbourne, 3000, on Tuesday 28 August at 7»45 p.n. The speaker will be Lloyd Edmonds who will talk about the Anti-Communist Referendum and the Communist Party Underground, Readers will remember that Lloyd has spoken to us before on the subject of his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, We look forward to another of his interesting talks, Bip: Red Book Fair The Big Red Book Pair, held at the Collingwood Town Hall on Saturday 14 July was a very successful occasion for all concerned. The organisers were pleased with the attendance and the $3,000 raised. With the exception of two rather excited and pugulistic book dealers, most of the buyers were pleased with the range of books available althoiigh the prices of some volmes designated 'rare' were rather high. However, as far as the Labour History Society was concerned, the Pair was very successful, A member of o\ir Canberra Executive, Eric Fry, came down to lead a seminar on the writing of labour history. It was a particularly well-attended seminar with about 50 people present, Eric's talk in opening discussion on the subject was very well received and encouraged many of those present to 'offer their opinions on how labour history might be written and to whom it might be directed. -

The Correspondence of American Doughboys and American Censorship During the Great War 1917-1918 Doctors of Letters Dissertation By

LETTERS FROM THE WESTERN FRONT: THE CORRESPONDENCE OF AMERICAN DOUGHBOYS AND AMERICAN CENSORSHIP DURING THE GREAT WAR 1917-1918 A dissertation submitted to the Caspersen School of Graduate Studies Drew University in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree, Doctor of Letters Scott L. Kent Drew University Madison, New Jersey April 2021 Copyright © 2021 by Scott L. Kent All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Letters from the Western Front: The Correspondence of American Doughboys and American Censorship during the Great War 1917-1918 Doctors of Letters Dissertation by Scott L. Kent The Caspersen School of Graduate Studies Drew University April 2021 Censorship has always been viewed by the American military as an essential weapon of warfare. The amounts, and types, of censorship deployed have varied from conflict to conflict. Censorship would reach a peak during America’s involvement in the First World War. The American military feared that any information could be of possible use to the German war machine, and it was determined to prevent any valuable information from falling into their hands. The result would be an unprecedented level of censorship that had no antecedent in American history. The censorship of the First World War came from three main directions, official censorship by the American government, by the American military, and the self- censorship of American soldiers themselves. Military censorship during the Great War was thorough and invasive. It began at the training camps and only intensified as the doughboys moved to their ports of embarkation, and then to the Western Front. Private letters were opened, read, censored, and even destroyed.