Guidance for Industry E2E Pharmacovigilance Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descriptive Statistics (Part 2): Interpreting Study Results

Statistical Notes II Descriptive statistics (Part 2): Interpreting study results A Cook and A Sheikh he previous paper in this series looked at ‘baseline’. Investigations of treatment effects can be descriptive statistics, showing how to use and made in similar fashion by comparisons of disease T interpret fundamental measures such as the probability in treated and untreated patients. mean and standard deviation. Here we continue with descriptive statistics, looking at measures more The relative risk (RR), also sometimes known as specific to medical research. We start by defining the risk ratio, compares the risk of exposed and risk and odds, the two basic measures of disease unexposed subjects, while the odds ratio (OR) probability. Then we show how the effect of a disease compares odds. A relative risk or odds ratio greater risk factor, or a treatment, can be measured using the than one indicates an exposure to be harmful, while relative risk or the odds ratio. Finally we discuss the a value less than one indicates a protective effect. ‘number needed to treat’, a measure derived from the RR = 1.2 means exposed people are 20% more likely relative risk, which has gained popularity because of to be diseased, RR = 1.4 means 40% more likely. its clinical usefulness. Examples from the literature OR = 1.2 means that the odds of disease is 20% higher are used to illustrate important concepts. in exposed people. RISK AND ODDS Among workers at factory two (‘exposed’ workers) The probability of an individual becoming diseased the risk is 13 / 116 = 0.11, compared to an ‘unexposed’ is the risk. -

Drug Safety in Translational Paediatric Research: Practical Points to Consider for Paediatric Safety Profiling and Protocol Development: a Scoping Review

pharmaceutics Review Drug Safety in Translational Paediatric Research: Practical Points to Consider for Paediatric Safety Profiling and Protocol Development: A Scoping Review Beate Aurich 1 and Evelyne Jacqz-Aigrain 1,2,* 1 Department of Pharmacology, Saint-Louis Hospital, 75010 Paris, France; [email protected] 2 Paris University, 75010 Paris, France * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Translational paediatric drug development includes the exchange between basic, clinical and population-based research to improve the health of children. This includes the assessment of treatment related risks and their management. The objectives of this scoping review were to search and summarise the literature for practical guidance on how to establish a paediatric safety specification and its integration into a paediatric protocol. PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and websites of regulatory authorities and learned societies were searched (up to 31 December 2020). Retrieved citations were screened and full texts reviewed where applicable. A total of 3480 publica- tions were retrieved. No article was identified providing practical guidance. An introduction to the practical aspects of paediatric safety profiling and protocol development is provided by combining health authority and learned society guidelines with the specifics of paediatric research. The paedi- atric safety specification informs paediatric protocol development by, for example, highlighting the Citation: Aurich, B.; Jacqz-Aigrain, E. need for a pharmacokinetic study prior to a paediatric trial. It also informs safety related protocol Drug Safety in Translational Paediatric Research: Practical Points sections such as exclusion criteria, safety monitoring and risk management. In conclusion, safety to Consider for Paediatric Safety related protocol sections require an understanding of the paediatric safety specification. -

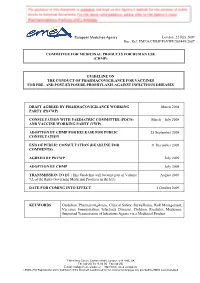

Guideline on the Conduct of Pharmacovigilance for Vaccines for Pre- and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Against Infectious Diseases

European Medicines Agency London, 22 July 2009 Doc. Ref. EMEA/CHMP/PhVWP/503449/2007 COMMITTEE FOR MEDICINAL PRODUCTS FOR HUMAN USE (CHMP) GUIDELINE ON THE CONDUCT OF PHARMACOVIGILANCE FOR VACCINES FOR PRE- AND POST-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS AGAINST INFECTIOUS DISEASES DRAFT AGREED BY PHARMACOVIGILANCE WORKING March 2008 PARTY (PhVWP) CONSULTATION WITH PAEDIATRIC COMMITTEE (PDCO) March – July 2008 AND VACCINE WORKING PARTY (VWP) ADOPTION BY CHMP FOR RELEASE FOR PUBLIC 25 September 2008 CONSULTATION END OF PUBLIC CONSULTATION (DEADLINE FOR 31 December 2008 COMMENTS) AGREED BY PhVWP July 2009 ADOPTION BY CHMP July 2009 TRANSMISSION TO EC (This Guideline will become part of Volume August 2009 9A of the Rules Governing Medicinal Products in the EU). DATE FOR COMING INTO EFFECT 1 October 2009 KEYWORDS Guideline, Pharmacovigilance, Clinical Safety, Surveillance, Risk Management, Vaccines, Immunisation, Infectious Diseases, Children, Paediatric Medicines, Suspected Transmission of Infectious Agents via a Medicinal Product 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 84 00 Fax (44-20) E-mail: [email protected] http://www.emea.europa.eu ©EMEA 2009 Reproduction and/or distribution of this document is authorised for non commercial purposes only provided the EMEA is acknowledged GUIDELINE ON THE CONDUCT OF PHARMACOVIGILANCE FOR VACCINES FOR PRE- AND POST-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS AGAINST INFECTIOUS DISEASES TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY_______________________________________________________ 3 1. Introduction ____________________________________________________________ -

Limitations of the Odds Ratio in Gauging the Performance of a Diagnostic, Prognostic, Or Screening Marker

American Journal of Epidemiology Vol. 159, No. 9 Copyright © 2004 by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Printed in U.S.A. All rights reserved DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwh101 Limitations of the Odds Ratio in Gauging the Performance of a Diagnostic, Prognostic, or Screening Marker Margaret Sullivan Pepe1,2, Holly Janes2, Gary Longton1, Wendy Leisenring1,2,3, and Polly Newcomb1 1 Division of Public Health Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA. 2 Department of Biostatistics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA. 3 Division of Clinical Research, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA. Downloaded from Received for publication June 24, 2003; accepted for publication October 28, 2003. A marker strongly associated with outcome (or disease) is often assumed to be effective for classifying persons http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/ according to their current or future outcome. However, for this assumption to be true, the associated odds ratio must be of a magnitude rarely seen in epidemiologic studies. In this paper, an illustration of the relation between odds ratios and receiver operating characteristic curves shows, for example, that a marker with an odds ratio of as high as 3 is in fact a very poor classification tool. If a marker identifies 10% of controls as positive (false positives) and has an odds ratio of 3, then it will correctly identify only 25% of cases as positive (true positives). The authors illustrate that a single measure of association such as an odds ratio does not meaningfully describe a marker’s ability to classify subjects. Appropriate statistical methods for assessing and reporting the classification power of a marker are described. -

Relative Risks, Odds Ratios and Cluster Randomised Trials . (1)

1 Relative Risks, Odds Ratios and Cluster Randomised Trials Michael J Campbell, Suzanne Mason, Jon Nicholl Abstract It is well known in cluster randomised trials with a binary outcome and a logistic link that the population average model and cluster specific model estimate different population parameters for the odds ratio. However, it is less well appreciated that for a log link, the population parameters are the same and a log link leads to a relative risk. This suggests that for a prospective cluster randomised trial the relative risk is easier to interpret. Commonly the odds ratio and the relative risk have similar values and are interpreted similarly. However, when the incidence of events is high they can differ quite markedly, and it is unclear which is the better parameter . We explore these issues in a cluster randomised trial, the Paramedic Practitioner Older People’s Support Trial3 . Key words: Cluster randomized trials, odds ratio, relative risk, population average models, random effects models 1 Introduction Given two groups, with probabilities of binary outcomes of π0 and π1 , the Odds Ratio (OR) of outcome in group 1 relative to group 0 is related to Relative Risk (RR) by: . If there are covariates in the model , one has to estimate π0 at some covariate combination. One can see from this relationship that if the relative risk is small, or the probability of outcome π0 is small then the odds ratio and the relative risk will be close. One can also show, using the delta method, that approximately (1). ________________________________________________________________________________ Michael J Campbell, Medical Statistics Group, ScHARR, Regent Court, 30 Regent St, Sheffield S1 4DA [email protected] 2 Note that this result is derived for non-clustered data. -

Understanding Relative Risk, Odds Ratio, and Related Terms: As Simple As It Can Get Chittaranjan Andrade, MD

Understanding Relative Risk, Odds Ratio, and Related Terms: As Simple as It Can Get Chittaranjan Andrade, MD Each month in his online Introduction column, Dr Andrade Many research papers present findings as odds ratios (ORs) and considers theoretical and relative risks (RRs) as measures of effect size for categorical outcomes. practical ideas in clinical Whereas these and related terms have been well explained in many psychopharmacology articles,1–5 this article presents a version, with examples, that is meant with a view to update the knowledge and skills to be both simple and practical. Readers may note that the explanations of medical practitioners and examples provided apply mostly to randomized controlled trials who treat patients with (RCTs), cohort studies, and case-control studies. Nevertheless, similar psychiatric conditions. principles operate when these concepts are applied in epidemiologic Department of Psychopharmacology, National Institute research. Whereas the terms may be applied slightly differently in of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India different explanatory texts, the general principles are the same. ([email protected]). ABSTRACT Clinical Situation Risk, and related measures of effect size (for Consider a hypothetical RCT in which 76 depressed patients were categorical outcomes) such as relative risks and randomly assigned to receive either venlafaxine (n = 40) or placebo odds ratios, are frequently presented in research (n = 36) for 8 weeks. During the trial, new-onset sexual dysfunction articles. Not all readers know how these statistics was identified in 8 patients treated with venlafaxine and in 3 patients are derived and interpreted, nor are all readers treated with placebo. These results are presented in Table 1. -

Ecological Impacts of Veterinary Pharmaceuticals: More Transparency – Better Protection of the Environment

Ecological Impacts of Veterinary Pharmaceuticals: More Transparency – Better Protection of the Environment Avoiding Environmental Pollution from Veterinary Pharmaceuticals To reduce the contamination of air, soil, and bodies of pharmaceuticals more stringently, monitoring systematically water caused by veterinary medicinal products used in their occurrence in the environment, converting animal hus- agriculture and livestock farming, effective measures bandry practices to preserve animals’ health with a minimal must be taken throughout the entire life cycle of these use of antibiotics, and enforcing legal regulations to ensure products – from production and authorisation to appli- implementation of all the measures outlined here. cation and disposal. In the context of the revision of veterinary medicinal products All stakeholders – whether they are farmers, veterinarians, legislation that is currently underway, this background paper consumers, or political decision makers – are called upon focuses on three measures that would contribute to mak- to contribute to reducing contamination of the environment ing information on the occurrence of veterinary drugs in the caused by pharmaceutical residues and to improving pro- environment and their eco-toxicological effects more widely tection of the environment and human health. Appropriate available and enhance protection of the environment from measures include establishing “clean” production plants, contamination with veterinary pharmaceuticals. developing pharmaceuticals with reduced environmental -

Outcome Reporting Bias in COVID-19 Mrna Vaccine Clinical Trials

medicina Perspective Outcome Reporting Bias in COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine Clinical Trials Ronald B. Brown School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON N2L3G1, Canada; [email protected] Abstract: Relative risk reduction and absolute risk reduction measures in the evaluation of clinical trial data are poorly understood by health professionals and the public. The absence of reported absolute risk reduction in COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials can lead to outcome reporting bias that affects the interpretation of vaccine efficacy. The present article uses clinical epidemiologic tools to critically appraise reports of efficacy in Pfzier/BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccine clinical trials. Based on data reported by the manufacturer for Pfzier/BioNTech vaccine BNT162b2, this critical appraisal shows: relative risk reduction, 95.1%; 95% CI, 90.0% to 97.6%; p = 0.016; absolute risk reduction, 0.7%; 95% CI, 0.59% to 0.83%; p < 0.000. For the Moderna vaccine mRNA-1273, the appraisal shows: relative risk reduction, 94.1%; 95% CI, 89.1% to 96.8%; p = 0.004; absolute risk reduction, 1.1%; 95% CI, 0.97% to 1.32%; p < 0.000. Unreported absolute risk reduction measures of 0.7% and 1.1% for the Pfzier/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, respectively, are very much lower than the reported relative risk reduction measures. Reporting absolute risk reduction measures is essential to prevent outcome reporting bias in evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine efficacy. Keywords: mRNA vaccine; COVID-19 vaccine; vaccine efficacy; relative risk reduction; absolute risk reduction; number needed to vaccinate; outcome reporting bias; clinical epidemiology; critical appraisal; evidence-based medicine Citation: Brown, R.B. -

Unlocking the Power of Pharmacovigilance* an Adaptive Approach to an Evolving Drug Safety Environment

Unlocking the power of pharmacovigilance* An adaptive approach to an evolving drug safety environment PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Health Research Institute Contents Executive summary 01 Background 02 The challenge to the pharmaceutical industry 02 Increased media scrutiny 02 Greater regulatory and legislative scrutiny 04 Investment in pharmacovigilance 05 The reactive nature of pharmacovigilance 06 Unlocking the power of pharmacovigilance 07 Organizational alignment 07 Operations management 07 Data management 08 Risk management 10 The three strategies of effective pharmacovigilance 11 Strategy 1: Align and clarify roles, responsibilities, and communications 12 Strategy 2: Standardize pharmacovigilance processes and data management 14 Strategy 3: Implement proactive risk minimization 20 Conclusion 23 Endnotes 24 Glossary 25 Executive summary The idea that controlled clinical incapable of addressing shifts in 2. Standardize pharmacovigilance trials can establish product safety public expectations and regulatory processes and data management and effectiveness is a core principle and media scrutiny. This reality has • Align operational activities across of the pharmaceutical industry. revealed issues in the four areas departments and across sites Neither the clinical trials process involved in patient safety operations: • Implement process-driven standard nor the approval procedures of the organizational alignment, operations operating procedures, work U.S. Food and Drug Administration management, data management, and instructions, and training -

Making Comparisons

Making comparisons • Previous sessions looked at how to describe a single group of subjects • However, we are often interested in comparing two groups Data can be interpreted using the following fundamental questions: • Is there a difference? Examine the effect size • How big is it? • What are the implications of conducting the study on a sample of people (confidence interval) • Is the effect real? Could the observed effect size be a chance finding in this particular study? (p-values or statistical significance) • Are the results clinically important? 1 Effect size • A single quantitative summary measure used to interpret research data, and communicate the results more easily • It is obtained by comparing an outcome measure between two or more groups of people (or other object) • Types of effect sizes, and how they are analysed, depend on the type of outcome measure used: – Counting people (i.e. categorical data) – Taking measurements on people (i.e. continuous data) – Time-to-event data Example Aim: • Is Ventolin effective in treating asthma? Design: • Randomised clinical trial • 100 micrograms vs placebo, both delivered by an inhaler Outcome measures: • Whether patients had a severe exacerbation or not • Number of episode-free days per patient (defined as days with no symptoms and no use of rescue medication during one year) 2 Main results proportion of patients Mean No. of episode- No. of Treatment group with severe free days during the patients exacerbation year GROUP A 210 0.30 (63/210) 187 Ventolin GROUP B placebo 213 0.40 (85/213) -

Causality in Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance: a Theoretical Excursion

DOI: 10.1590/1980-5497201700030010 ARTIGO ORIGINAL / ORIGINAL ARTICLE Causalidade em farmacoepidemiologia e farmacovigilância: uma incursão teórica Causality in Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance: a theoretical excursion Daniel Marques MotaI,II, Ricardo de Souza KuchenbeckerI RESUMO: O artigo teceu algumas considerações sobre causalidade em farmacoepidemiologia e farmacovigilância. Inicialmente, fizemos uma breve introdução sobre a importância do tema, ressaltando que o entendimento da relação causal é considerado como uma das maiores conquistas das ciências e que tem sido, ao longo dos tempos, uma preocupação contínua e central de filósofos e epidemiologistas. Na sequência, descrevemos as definições e os tipos de causas, demonstrando suas influências no pensamento farmacoepidemiológico. Logo a seguir, apresentamos o modelo multicausal de Rothman como um dos fundantes para a explicação da causalidade múltipla, e o tema da determinação da causalidade. Concluímos com alguns comentários e reflexões sobre causalidade na perspectiva da vigilância sanitária, particularmente, para as ações de regulação em farmacovigilância. Palavras-chave: Aplicações da epidemiologia. Causalidade. Efeitos colaterais e reações adversas relacionados a medicamentos. Farmacoepidemiologia. Farmacovigilância. Vigilância sanitária. IPrograma de Pós-Graduação em Epidemiologia, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul – Porto Alegre (RS), Brasil. IIAgência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária – Brasília (DF), Brasil. Autor correspondente: Daniel Marques Mota. Programa de Pós-Gradução em Epidemiologia da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Rua Ramiro Barcelos, 2.400, 2º andar, CEP: 90035-003, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] Conflito de interesses: nada a declarar – Fonte de financiamento: nenhuma. 475 REV BRAS EPIDEMIOL JUL-SET 2017; 20(3): 475-486 MOTA, D.M., KUCHENBECKER, R.S. -

Relative Risk Cutoffs For-Statistical-Significance

V0b Relative Risk Cutoffs for Statistical Significance 2014 Milo Schield, Augsburg College Abstract: Relative risks are often presented in the everyday media but are seldom mentioned in introductory statistics courses or textbooks. This paper reviews the confidence interval associated with a relative risk ratio. Statistical significance is taken to be any relative risk where the associated 90% confidence interval does not include unity. The exact solution for the minimum statistically-significant relative risk is complex. A simple iterative solution is presented. Several simplifications are examined. A Poisson solution is presented for those times when the Normal is not justified. 1. Relative risk in the everyday media In the everyday media, relative risks are presented in two ways: explicitly using the phrase “relative risk” or implicitly involving an explicit comparison of two rates or percentages, or by simply presenting two rates or percentages from which a comparison or relative risk can be easily generated. Here are some examples (Burnham, 2009): the risk of developing acute non-lymphoblastic leukaemia was seven times greater compared with children who lived in the same area , but not next to a petrol station Bosch and colleagues ( p 699 ) report that the relative risk of any stroke was reduced by 32 % in patients receiving ramipril compared with placebo Women of normal weight and who were physically active but had high glycaemic loads and high fructose intakes were also at greater risk (53 % and 57 % increase respectively ) than