Those Goddamn Ointments: Four Histories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magic and the Supernatural

Edited by Scott E. Hendrix and Timothy J. Shannon Magic and the Supernatural At the Interface Series Editors Dr Robert Fisher Dr Daniel Riha Advisory Board Dr Alejandro Cervantes-Carson Dr Peter Mario Kreuter Professor Margaret Chatterjee Martin McGoldrick Dr Wayne Cristaudo Revd Stephen Morris Mira Crouch Professor John Parry Dr Phil Fitzsimmons Paul Reynolds Professor Asa Kasher Professor Peter Twohig Owen Kelly Professor S Ram Vemuri Revd Dr Kenneth Wilson, O.B.E An At the Interface research and publications project. http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/at-the-interface/ The Evil Hub ‘Magic and the Supernatural’ 2012 Magic and the Supernatural Edited by Scott E. Hendrix and Timothy J. Shannon Inter-Disciplinary Press Oxford, United Kingdom © Inter-Disciplinary Press 2012 http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/publishing/id-press/ The Inter-Disciplinary Press is part of Inter-Disciplinary.Net – a global network for research and publishing. The Inter-Disciplinary Press aims to promote and encourage the kind of work which is collaborative, innovative, imaginative, and which provides an exemplar for inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of Inter-Disciplinary Press. Inter-Disciplinary Press, Priory House, 149B Wroslyn Road, Freeland, Oxfordshire. OX29 8HR, United Kingdom. +44 (0)1993 882087 ISBN: 978-1-84888-095-5 First published in the United Kingdom in eBook format in 2012. First Edition. Table of Contents Preface vii Scott Hendrix PART 1 Philosophy, Religion and Magic Magic and Practical Agency 3 Brian Feltham Art, Love and Magic in Marsilio Ficino’s De Amore 9 Juan Pablo Maggioti The Jinn: An Equivalent to Evil in 20th Century 15 Arabian Nights and Days Orchida Ismail and Lamya Ramadan PART 2 Magic and History Rational Astrology and Empiricism, From Pico to Galileo 23 Scott E. -

Black Magic & White Supremacy

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 2-23-2021 Black Magic & White Supremacy: Witchcraft as an Allegory for Race and Power Nicholas Charles Peters Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Peters, Nicholas Charles, "Black Magic & White Supremacy: Witchcraft as an Allegory for Race and Power" (2021). University Honors Theses. Paper 962. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.986 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Black Magic & White Supremacy: Witchcraft as an Allegory for Race and Power By Nicholas Charles Peters An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in English and University Honors Thesis Adviser Dr. Michael Clark Portland State University 2021 1 “Being burned at the stake was an empowering experience. There are secrets in the flames, and I came back with more than a few” (Head 19’15”). Burning at the stake is one of the first things that comes to mind when thinking of witchcraft. Fire often symbolizes destruction or cleansing, expelling evil or unnatural things from creation. “Fire purges and purifies... scatters our enemies to the wind. -

The Mandrake and the Ancient World,” the Evangelical Quarterly 28.2 (1956): 87-92

R.K. Harrison, “The Mandrake And The Ancient World,” The Evangelical Quarterly 28.2 (1956): 87-92. The Mandrake and the Ancient World R.K. Harrison [p.87] Professor Harrison, of the Department of Old Testament in Huron College, University of Western Ontario, has already shown by articles in THE EVANGELICAL QUARTERLY his interest and competence in the natural history of the Bible. Here he examines one of the more curious Biblical plants. The mandrake is one of the plants which still grows widely in the Middle East, and which has claimed magical associations from a very remote period. It is generally assigned the botanical name of Mandragora officinarum L..1 and is a perennial of the order Solanaceae. It claims affinity with the potato and eggplant, and is closely allied to the Atropa belladonna L.,2 with which it is not infrequently confused by some writers. The modern Arab knows it by a number of names, including Tuffah£ el Majanin (‘Madmen’s Apple) and Beid el Jinn (Eggs of the Jinn), apparently a reference to the ability of the plant to invigorate and stimulate the senses even to the point of mental imbalance. The former name may perhaps be a survival of the belief found in Oriental folk-lore regarding the magical herb Baaras, with which the mandrake is identified by some authorities.3 According to the legends associated with this plant, it was highly esteemed amongst the ancients on account of its pronounced magical properties. But because of the potency of these attributes it was an extremely hazardous undertaking for anyone to gather the plant, and many who attempted it were supposed to have paid for their daring with [p.88] sickness and death.4 Once the herb had been gathered, however, it availed for a number of diseases, and in antiquity it was most reputed for its ability to cure depression and general disorders of the mind. -

The Synagogue of Satan

THE SYNAGOGUE OF SATAN BY MAXIMILIAN J. RUDWIN THE Synagogue of Satan is of greater antiquity and potency than the Church of God. The fear of a mahgn being was earher in operation and more powerful in its appeal among primitive peoples than the love of a benign being. Fear, it should be re- membered, was the first incentive of religious worship. Propitiation of harmful powers was the first phase of all sacrificial rites. This is perhaps the meaning of the old Gnostic tradition that when Solomon was summoned from his tomb and asked, "Who first named the name of God?" he answered, "The Devil." Furthermore, every religion that preceded Christianity was a form of devil-worship in the eyes of the new faith. The early Christians actually believed that all pagans were devil-worshippers inasmuch as all pagan gods were in Christian eyes disguised demons who caused themselves to be adored under different names in dif- ferent countries. It was believed that the spirits of hell took the form of idols, working through them, as St. Thomas Aquinas said, certain marvels w'hich excited the wonder and admiration of their worshippers (Siiinina theologica n.ii.94). This viewpoint was not confined to the Christians. It has ever been a custom among men to send to the Devil all who do not belong to their own particular caste, class or cult. Each nation or religion has always claimed the Deity for itself and assigned the Devil to other nations and religions. Zoroaster described alien M^orshippers as children of the Divas, which, in biblical parlance, is equivalent to sons of Belial. -

Drugs That Can Cause Delirium (Anticholinergic / Toxic Metabolites)

Drugs that can Cause Delirium (anticholinergic / toxic metabolites) Deliriants (drugs causing delirium) Prescription drugs . Central acting agents – Sedative hypnotics (e.g., benzodiazepines) – Anticonvulsants (e.g., barbiturates) – Antiparkinsonian agents (e.g., benztropine, trihexyphenidyl) . Analgesics – Narcotics (NB. meperidine*) – Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs* . Antihistamines (first generation, e.g., hydroxyzine) . Gastrointestinal agents – Antispasmodics – H2-blockers* . Antinauseants – Scopolamine – Dimenhydrinate . Antibiotics – Fluoroquinolones* . Psychotropic medications – Tricyclic antidepressants – Lithium* . Cardiac medications – Antiarrhythmics – Digitalis* – Antihypertensives (b-blockers, methyldopa) . Miscellaneous – Skeletal muscle relaxants – Steroids Over the counter medications and complementary/alternative medications . Antihistamines (NB. first generation) – diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine). Antinauseants – dimenhydrinate, scopolamine . Liquid medications containing alcohol . Mandrake . Henbane . Jimson weed . Atropa belladonna extract * Requires adjustment in renal impairment. From: K Alagiakrishnan, C A Wiens. (2004). An approach to drug induced delirium in the elderly. Postgrad Med J, 80, 388–393. Delirium in the Older Person: A Medical Emergency. Island Health www.viha.ca/mhas/resources/delirium/ Drugs that can cause delirium. Reviewed: 8-2014 Some commonly used medications with moderate to high anticholinergic properties and alternative suggestions Type of medication Alternatives with less deliriogenic -

Ritualized Peyote Use Can Facilitate Mental Health, Social Solidarity

Ritualized Peyote Use Can Facilitate Mental Health, Social Solidarity, and Cultural Survival: A Case Study of the Religious and Mystical Experiences in the Wixárika People of the Sierra Madre Occidental The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Luce, Nathan William. 2020. Ritualized Peyote Use Can Facilitate Mental Health, Social Solidarity, and Cultural Survival: A Case Study of the Religious and Mystical Experiences in the Wixárika People of the Sierra Madre Occidental. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37365056 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Ritualized Peyote Use Can Facilitate Mental Health, Social Solidarity, and Cultural Survival: A Case Study of the Religious and Mystical Experiences in the Wixárika People of the Sierra Madre Occidental Nathan William Luce A Thesis in the Field of Religion for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2020 Copyright 2020 Nathan William Luce Abstract This paper examines how the Wixárika, or Huichol, as they are more commonly known to the outside world, have successfully engaged in a decade-long struggle to save their ceremonial homeland of Wirikuta. They have fended off a Canadian silver mining company’s attempts to dig mines in the habitat of their most important sacrament, peyote, using a remarkable combination of traditional and modern resistance techniques. -

PSYCHEDELIC DRUGS (P.L) 1. Terminology “Hallucinogens

PSYCHEDELIC DRUGS (p.l) 1. Terminology “hallucinogens” – induce hallucinations, although sensory distortions are more common “psychotomimetics” – to minic psychotic states, although truly most drugs in this class do not do so “phantasticums”or “psychedelics” – alter sensory perception (Julien uses “psychedelics”) alterations in perception, cognition, and mood, in presence of otherwise clear ability to sense” may increase sensory awareness, increase clarity, decrease control over what is sensed/experienced “self-A” may feel a passive observer of what “self-B” is experiencing often accompanied by a sense of profound meaningfulness, of divine or cosmic importance (limbic system?) these drugs can be classified by what NT they mimic: anti-ACh, agonists for NE, 5HT, or glutamate (See p. 332, Table 12.l in Julien, 9th Ed.) 2. The Anti-ACh Psychedelics e.g. scopolamine (classified as an ACh blocker) high affinity, no efficacy plant product: Belladonna or “deadly nightshade” (Atropa belladonna) Datura stramonium (jimson weed, stinkweed) Mandragora officinarum (mandrake plant) pupillary dilation (2nd to atropine) PSYCHEDELIC DRUGS (p.2) 2. Anti-ACh Psychedelics (cont.) pharmacological effects: e.g. scopolamine (Donnatal) clinically used to tx motion sickness, relax smooth muscles (gastric cramping), mild sedation/anesthetic effect PNS effects --- dry mouth relaxation of smooth muscles decreased sweating increased body temperature blurred vision dry skin pupillary dilation tachycardia, increased BP CNS effects --- drowsiness, mild euphoria profound amnesia fatigue decreased attention, focus delirium, mental confusion decreased REM sleep no increase in sensory awareness as dose increases --- restlessness, excitement, hallucinations, euphoria, disorientation at toxic dose levels --- “psychotic delirium”, confusion, stupor, coma, respiratory depression so drug is really an intoxicant, amnestic, and deliriant 3. -

Witch Hunting

LE TAROT- ISTITUTO GRAF p resen t WITCH HUNTING C U R A T O R S FRANCO CARDINI - ANDREA VITALI GUGLIELMO INVERNIZZI - GIORDANO BERTI 1 HISTORICAL PRESENTATION “The sleep of reason produces monsters" this is the title of a work of the great Spanish painter Francisco Goya. He portrayed a man sleeping on a large stone, while around him there were all kinds of nightmares, who become living beings. With this allegory, Goya was referring to tragedies that involved Europe in his time, the end of the eighteenth century. But the same image can be the emblem of other tragedies closer to our days, nightmares born from intolerance, incomprehension of different people, from the illusion of intellectual, religious or racial superiority. The history of the witch hunting is an example of how an ancient nightmare is recurring over the centuries in different forms. In times of crisis, it is seeking a scapegoat for the evils that afflict society. So "the other", the incarnation of evil, must be isolated and eliminated. This irrational attitude common to primitive cultures to the so-called "civilization" modern and post-modern. The witch hunting was break out in different locations of Western Europe, between the Middle Ages and the Baroque age. The most affected areas were still dominated by particular cultures or on the border between nations in conflict for religious reasons or for political interests. Subtly, the rulers of this or that nation shake the specter of invisible and diabolical enemy to unleash fear and consequent reaction: the denunciation, persecution, extermination of witches. -

The Host in the Toad PDF

Cor Hendriks The Host in the Toad The Development of a Fairytale Motif (V34.2) In Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk-Literature we find under V34. Miraculous working of the host as subdivision V34.2. Princess sick because toad has swallowed her consecrated wafer. Thompson refers for this to Tale Type 613 and the study of this type by Christiansen. Other motifs he refers to are B177. Magic Toad; C55. Tabu: losing consecrated wafer; C940.1. Princess’s secret sickness from breaking tabu; D2064.1. Magic sickness because girl has thrown away her consecrated wafer. At this last motif Thompson remarks: H1292.4.1. Question (propounded on quest): How can the princess be cured? Answer: She must recover consecrated wafer which rat has stolen from her first communion. 1 This question of how the princess can be cured is treated by Christiansen in his study of AT 613 and he remarks that the list of the different remedies is long, and that it is difficult to settle a tradition. A certain feature though he finds in some of the variants, more fully worked out or simply suggested: it is the incident that the princess’s disease was due to a mishap at her first communion, where she lost the consecrated wafer. A toad took it, and is sitting under the floor with it in its mouth, and it has to be given back to the princess (also a rat is found). This episode can be seen in 4 Norse, 1 Swedish, 4 Danish, 2 Icelandic, 2 German, 1 Dutch, 2 Belgian, 2 Czech, 1 Hungarian, 1 Bask, 1 Rumanian, 1 Slovak, 4 Finnish, 2 Russian, 2 White- Russian; and 6 Polish versions. -

Sorcerer”? Find 18 Synonyms and 30 Related Words for “Sorcerer” in This Overview

Need another word that means the same as “sorcerer”? Find 18 synonyms and 30 related words for “sorcerer” in this overview. Table Of Contents: Sorcerer as a Noun Definitions of "Sorcerer" as a noun Synonyms of "Sorcerer" as a noun (18 Words) Associations of "Sorcerer" (30 Words) The synonyms of “Sorcerer” are: magician, necromancer, thaumaturge, thaumaturgist, wizard, witch, black magician, warlock, diviner, occultist, sorceress, enchanter, enchantress, magus, medicine man, medicine woman, shaman, witch doctor Sorcerer as a Noun Definitions of "Sorcerer" as a noun According to the Oxford Dictionary of English, “sorcerer” as a noun can have the following definitions: A person who claims or is believed to have magic powers; a wizard. One who practices magic or sorcery. GrammarTOP.com Synonyms of "Sorcerer" as a noun (18 Words) A person with dark skin who comes from Africa (or whose ancestors black magician came from Africa. Someone who claims to discover hidden knowledge with the aid of diviner supernatural powers. enchanter A sorcerer or magician. enchantress A woman who is considered to be dangerously seductive. A conjuror. magician He was the magician of the fan belt. GrammarTOP.com magus A sorcerer. medicine man Punishment for one’s actions. medicine woman Punishment for one’s actions. A person who practises necromancy; a wizard or magician. necromancer Dr Faustus a necromancer of the 16th century. occultist A believer in occultism; someone versed in the occult arts. In societies practicing shamanism one acting as a medium between shaman the visible and spirit worlds practices sorcery for healing or divination. sorceress A woman sorcerer. -

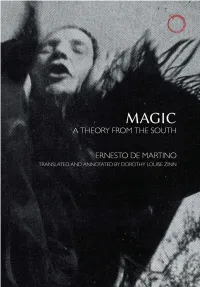

Magic: a Theory from the South

MAGIC Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com Magic A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH Ernesto de Martino Translated and Annotated by Dorothy Louise Zinn Hau Books Chicago © 2001 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano (First Edition, 1959). English translation © 2015 Hau Books and Dorothy Louise Zinn. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-9-9 LCCN: 2014953636 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Translator’s Note vii Preface xi PART ONE: LUcanian Magic 1. Binding 3 2. Binding and eros 9 3. The magical representation of illness 15 4. Childhood and binding 29 5. Binding and mother’s milk 43 6. Storms 51 7. Magical life in Albano 55 PART TWO: Magic, CATHOliciSM, AND HIGH CUltUre 8. The crisis of presence and magical protection 85 9. The horizon of the crisis 97 vi MAGIC: A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH 10. De-historifying the negative 103 11. Lucanian magic and magic in general 109 12. Lucanian magic and Southern Italian Catholicism 119 13. Magic and the Neapolitan Enlightenment: The phenomenon of jettatura 133 14. Romantic sensibility, Protestant polemic, and jettatura 161 15. The Kingdom of Naples and jettatura 175 Epilogue 185 Appendix: On Apulian tarantism 189 References 195 Index 201 Translator’s Note Magic: A theory from the South is the second work in Ernesto de Martino’s great “Southern trilogy” of ethnographic monographs, and following my previous translation of The land of remorse ([1961] 2005), I am pleased to make it available in an English edition. -

Sane Magic Item Prices

Introduction • Consumables are items that are used some set Have you ever wondered how much an item truly costs? amount of times (usually once) and then are gone. Have you been wanting to find or craft an item but aren’t • Combat Items are items that primarily make the sure how it fits in to the grand scheme of things? Did you user better at killing things. Some also have other ever look at sovereign glue and say to yourself, “There is killing-unrelated effects, but these are not the no way that glue is worth 500,000 gp when Sentinal shield primary source of their utility. is worth 500gp”. Well you are in luck because this guide • Noncombat Items are items that primarily make is for you. the user better at solving problems in a killing- Brainstorming with the Giant In the Playground, /r/ unrelated manner. Some also make the user better DnDNext, and EnWorld forums, Saidoro has put together at killing things, but this is not the primary source a set of tables that break down the costs, reasons for the of their utility. costs, and DMG page to find the item. • Summoning Items are items that summon creatures to kill things or solve problems for you. • Gamechanging Items are items that can have major DM Preface effects on the way the players engage with the world Your world need not sell the magic items for the prices or that can resculpt the campaign world in some given below. Your world does not even need to sell the major way all on their own.