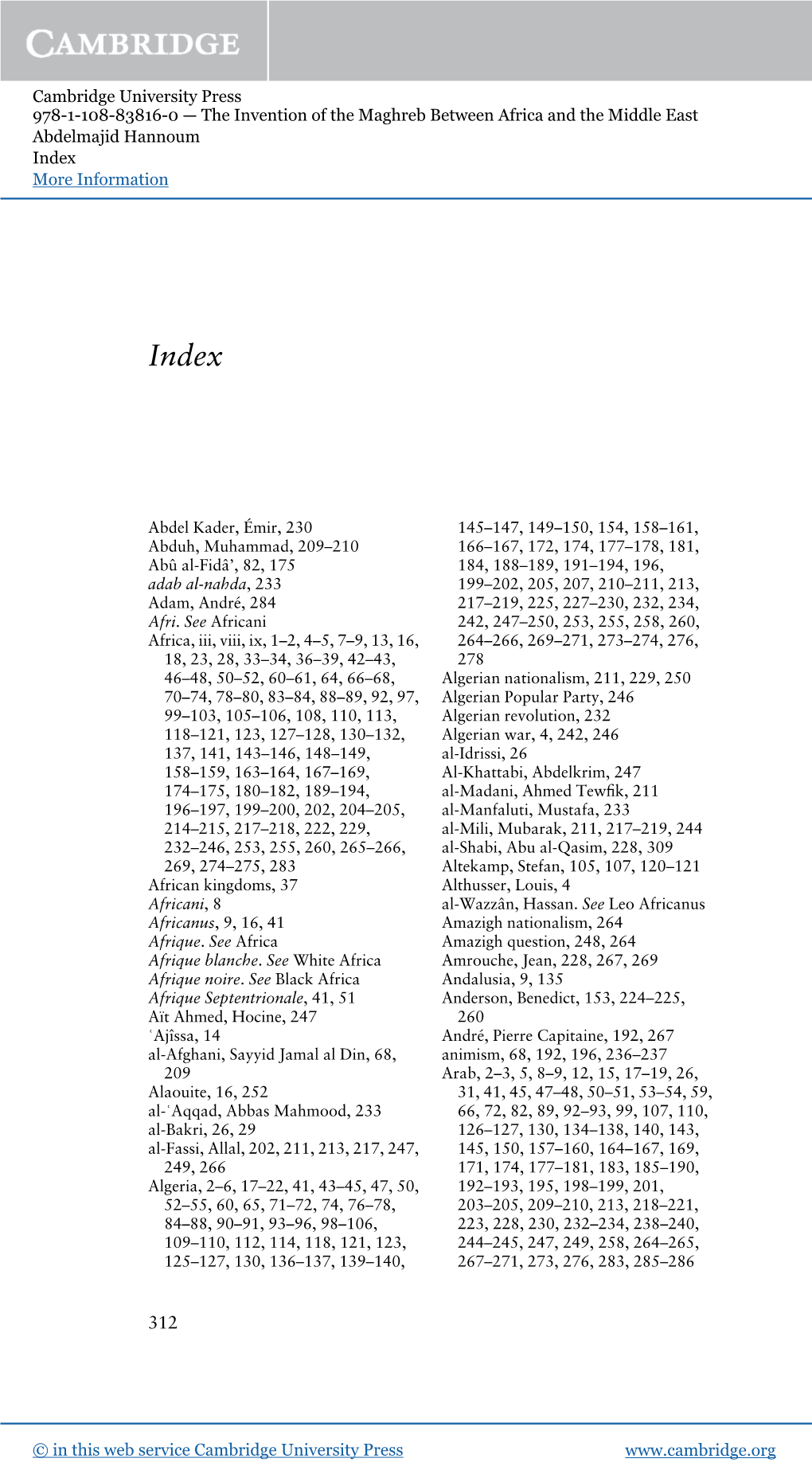

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-83816-0 — the Invention of the Maghreb Between Africa and the Middle East Abdelmajid Hannoum Index More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Professorial Chair (Kursi ‘Ilmi Or Kursi Li-L-Wa‘Z Wa-L-Irshad) in Morocco La Cátedra (Kursi ‘Ilmi O Kursi Li-L-Wa‘Z Wa-L-Irsad) En Marruecos

Maqueta Alcantara_Maquetación 1 30/05/13 12:50 Página 89 AL-QANTARA XXXIV 1, enero-junio 2013 pp. 89-122 ISSN 0211-3589 doi: 10.3989/alqantara.2013.004 The Professorial Chair (kursi ‘ilmi or kursi li-l-wa‘z wa-l-irshad) in Morocco La cátedra (kursi ‘ilmi o kursi li-l-wa‘z wa-l-irsad) en Marruecos Nadia Erzini Stephen Vernoit Tangier, Morocco Las mezquitas congregacionales en Marruecos Moroccan congregational mosques are suelen tener un almimbar (púlpito) que se uti- equipped with a minbar (pulpit) which is used liza durante el sermón de los viernes. Muchas for the Friday sermon. Many mosques in Mo- mezquitas de Marruecos cuentan también con rocco are also equipped with one or more una o más sillas, diferenciadas del almimbar smaller chairs, which differ in their form and en su forma y su función ya que son utilizadas function from the minbar. These chairs are por los profesores para enseñar a los estudian- used by professors to give regular lectures to tes de la educación tradicional, y por eruditos students of traditional education, and by schol- que dan conferencias ocasionales al público ars to give occasional lectures to the general en general. Esta tradición de cátedras se intro- public. This tradition of the professorial chair duce probablemente en Marruecos desde Pró- was probably introduced to Morocco from the ximo Oriente en el siglo XIII. La mayoría de Middle East in the thirteenth century. Most of las cátedras existentes parecen datar de los si- the existing chairs in Morocco seem to date glos XIX y XX, manteniéndose hasta nuestros from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, días la fabricación y utilización de estas sillas. -

Leo the African Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LEO THE AFRICAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Amin Maalouf | 368 pages | 22 Sep 1994 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780349106007 | English | London, United Kingdom Leo the African PDF Book A scholarly translation into French with extensive notes. Views Read Edit View history. Read more Read less. Wikimedia Commons. Usually dispatched within 4 to 5 days. By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Notice. London: G. Leo the African was first published in French in , and the first English translation appeared several years later. See also: Description of Africa book. Amin Maalouf. Black, Crofton It is a curious habit of men, al-Wazzan notes, to name themselves after terrifying beasts instead of devoted animals. If the Amazon. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. This fictional work on a larger than life real life character. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Maalouf's al-Wazzan is less passionate than the reader about his remarkable life. Report abuse. First paperback edition cover. I just can't help but recommending it to everybody. The original text of Pory's English translation together with an introduction and notes by the editor. The Song of Roland Book Analysis. Dewey Decimal. Another surviving work is a biographical encyclopedia of 25 major Islamic scholars and 5 major Jewish scholars. Historical reenactment History play Historical grand opera by historical figures. Helsinki: Finnish Academy of Science and Letters. Routledge, He is a poet to sultans and lover to wives, slave-girls and princesses. Hunwick, John O. He continued with his journey through Cairo and Aswan and across the Red Sea to Arabia , where he probably performed a pilgrimage to Mecca. -

The Persistence of the Andalusian Identity in Rabat, Morocco

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 1995 The Persistence of the Andalusian Identity in Rabat, Morocco Beebe Bahrami University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ethnic Studies Commons, European History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Bahrami, Beebe, "The Persistence of the Andalusian Identity in Rabat, Morocco" (1995). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1176. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1176 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1176 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Persistence of the Andalusian Identity in Rabat, Morocco Abstract This thesis investigates the problem of how an historical identity persists within a community in Rabat, Morocco, that traces its ancestry to Spain. Called Andalusians, these Moroccans are descended from Spanish Muslims who were first forced to convert to Christianity after 1492, and were expelled from the Iberian peninsula in the early seventeenth century. I conducted both ethnographic and historical archival research among Rabati Andalusian families. There are four main reasons for the persistence of the Andalusian identity in spite of the strong acculturative forces of religion, language, and culture in Moroccan society. First, the presence of a strong historical continuity of the Andalusian heritage in North Africa has provided a dominant history into which the exiled communities could integrate themselves. Second, the predominant practice of endogamy, as well as other social practices, reinforces an intergenerational continuity among Rabati Andalusians. Third, the Andalusian identity is a single identity that has a complex range of sociocultural contexts in which it is both meaningful and flexible. -

Al-Quarawiyine University

MAS Journal of Applied Sciences 6(3): 789–795, 2021 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52520/masjaps.108 Derleme Makalesi The First University in the World: Al-Quarawiyine University Hiba Abdouni1* 1Istanbul Aydın University, Department of Political Science and International Relations *Sorumlu yazar: [email protected] Geliş Tarihi: 19.03.2021 Kabul Tarihi: 25.04.2021 Abstract Most people would suppose that the first and oldest university in the world is in Europe. The first university in the world is in North-Africa Morocco and it was founded by the Tunisian Muslim woman Fatima Al-Fihri. The aim of the article is to raise awareness about the important role of this university and how it encouraged researches and scientists from all over the globe. In addition to this, most people are not aware of the existence of this university even though it was actually recognized by the UNESCO and the Guiness World Records. So, another aim of this article, is to make readers fully aware about how the idea of “University” was introduced for the first time in Morocco and then later expanded to the rest of the world. This article will also present a number of famous scholars who studied at Al-Quarawiyine University as well as how the university was being funded during that time. Anahtar Kelimeler: Morocco, fatima al-fihri, al-quarawiyine university, unesco, guinness world records, famous scholars 789 MAS Journal of Applied Sciences 6(3): 789–795, 2021 INTRODUCTION recommended was not the Arabic of the Morocco is known for its long- people, but instead that of the Quran. -

Leo Africanus' Description of West Africa (1500) Leo Africanus Leo Africanus

Leo Africanus' Description of West Africa (1500) Leo Africanus Leo Africanus. 1896. The History and Description of Africa and of the Notable Things Therein Contained. Edited by Dr. Robert Brown and Translated by John Pory. London: Hakluyt Society. Leo Africanus was an early-sixteenth-century traveler who recorded in great detail the life of many remote African kingdoms. His work, The History and Description of Africa and of the Notable Things Therein Contained, was translated from Arabic for the first time into Latin in 1526. Little is actually known of the early life of Leo except that he was born in Granada and later moved to Fez, a great commercial center in the Sudan and a seat of learning with many mosques and libraries. It was obvious to Pope Leo X, after meeting the Moorish slave, that Leo was originally from a wealthy family and educated. Leo's account of his travels throughout the Sudan were particularly important because it described the region just when Songhai had been raised to its political and economic zenith by the conquests of Askia Muhammad (1493-1528). His accounts clearly show that regional and international trade played a dominant part in the economic life of the entire Maghrib. The rich city of Timbuktu, the large armies of the kings, the wide variety of goods sold by merchants, and the intellectual and cultural life of the Muslim inhabitants of the Songhai Empire were all described in fascinating detail. Cartographers in Europe redrew the map of Africa in light of Leo's documentary, and for two-and-a-half centuries, his travel accounts were an indispensable source of knowledge to all concerned with the study of Africa. -

Morocco in the Early Atlantic World, 1415-1603 A

MOROCCO IN THE EARLY ATLANTIC WORLD, 1415-1603 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Earnest W. Porta, Jr., J.D. Washington, DC June 20, 2018 Copyright 2018 by Earnest W. Porta, Jr. All Rights Reserved ii MOROCCO IN THE EARLY ATLANTIC WORLD, 1415-1603 Earnest W. Porta, Jr., J.D. Dissertation Advisor: Osama Abi-Mershed, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Over the last several decades, a growing number of historians have conceptualized the Atlantic world as an explanatory analytical framework, useful for studying processes of interaction and exchange. Stretching temporally from the 15th into the 19th century, the Atlantic world framework encompasses more than simply the history of four continents that happen to be geographically situated around what we now recognize as the Atlantic basin. It offers instead a means for examining and understanding the transformative impacts that arose from the interaction of European, African, and American cultures following the European transatlantic voyages of the 15th and 16th centuries. Though it has not been extensively studied from this perspective, during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Morocco possessed geopolitical characteristics that uniquely situated it within not only the Islamic world, but the developing Atlantic world as well. This study considers Morocco’s involvement in the early Atlantic world by examining three specific phases of its involvement. The first phase lasts approximately one hundred years and begins with the Portuguese invasion of Ceuta in 1415, considered by some to mark the beginning of European overseas expansion. -

The 3Rd International Conference on African Digital Libraries And

Said ENNAHID, AUI, Morocco, 2013 The 3rd International Conference on African Digital Libraries and Archives Digital Libraries and Archives in Africa: Changing Lives and Building Communities (ICADLA-3) 27 – 29 May, 2013 Al Akhawayn University, Ifrane, Morocco TOWARDS A DIGITAL LIBRARY FOR MANUSCRIPT COLLECTIONS IN MOROCCO Said ENNAHID, Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane, Morocco Manuscript Collections in Morocco in Historical Perspective The corpus of Moroccan manuscripts is estimated at more than 80,000 titles and 200,000 volumes1 held at a number of public and private libraries—mostly religious institutions and zawāyā.2 These collections are invaluable both as repositories of human knowledge and memory and for their aesthetic value in terms of calligraphy, illumination, iconography and craftsmanship. Several medieval authors position Morocco as an important center in the Muslim West (al-Gharb al-Islami) for manuscript production, illumination, binding and exchange. However, except for a few scattered publications, a history of North African Arabic calligraphy (al-khatt al-maghribi) remains to be written. By providing the tools for making these collections readily accessible to the scholarly community in the Maghrib and beyond, ICT will make possible the study of North African scripts within the broader context of Arabic calligraphy and the Islamic arts of the book in general. The two main manuscript collections in Morocco are hosted at the National Library of Morocco (Bibliothèque nationale du royaume du Maroc, or BNRM, formerly General -

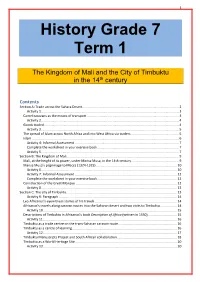

History Grade 7 Term 1

1 History Grade 7 Term 1 The Kingdom of Mali and the City of Timbuktu in the 14th century Contents Section A: Trade across the Sahara Desert ........................................................................................................ 2 Activity 1 .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Camel caravans as the means of transport ................................................................................................... 3 Activity 2 .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Goods traded ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Activity 3 .................................................................................................................................................... 5 The spread of Islam across North Africa and into West Africa via traders ................................................... 5 Islam .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Activity 4: Informal Assessment ................................................................................................................ 7 Complete the worksheet in your exercise book. ...................................................................................... -

Leo Africanus: Description of Timbuktu from the Description of Africa(1526)

Leo Africanus: Description of Timbuktu from The Description of Africa(1526) El Hasan ben Muhammed el-Wazzan-ez-Zayyati was born in the Moorish city of Granada in 1485, but was expelled along with his parents and thousands of other Muslims by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492. Settling in Morocco, he studied in Fez, and as a teenager accompanied his uncle on diplomatic missions throughout North Africa and and to the Sub-Saharan kingdom of Ghana. Still a young man, he was captured by Christian pirates and presented as an exceptionally learned slave to the great Renaissance pope, Leo X. Leo freed him, baptised him under the name "Johannis Leo de Medici," and commissioned him to write in Italian the detailed survey of Africa which provided most of what Europeans knew about the continent for the next several centuries. At the time he visited the Ghanaian city of Timbuktu, it was somewhat past its peak, but still a thriving Islamic city famous for its learning. "Timbuktu" was to become a byword in Europe as the most inaccessible of cities, but at the time Leo visited, it was the center of a busy trade in African products and in books. Leo is said to have died in 1554 in Tunis, having reconverted to Islam. What evidence does he provide that suggests the importance of learning in Timbuktu? The name of this kingdom is a modern one, after a city which was built by a king named Mansa Suleyman in the year 610 of the hegira [1232 CE] around twelve miles from a branch of theNiger River. -

Cartography of Al-Sharif Al-Idrisi

7 • Cartography of aI-SharIf aI-IdrIsI s. MAQBUL AHMAD AI-Idrlsl was born in Ceuta, Morocco, in 493/1100.1 He known as the Book of Roger (containing a small world belonged to the house of the (AlawI Idrislds, claimants map and seventy sectional maps). These can be rated as to the caliphate, who ruled the region around Ceuta from the zenith of Islamic-Norman geographical collabora A.D. 789 to 985; hence his title "aI-Sharif" (the noble) al tion. The task of constructing the world map and pro IdrlsL His ancestors were the nobles of Malaga, but ducing the book was accomplished in the month of unable to maintain their authority, they migrated to Ceuta Shawwal548 (January 1154). After Roger's death in 548/ in the eleventh century. AI-Idrlsl was educated in Cor 1154, al-Idrlsi continued to work at the court of his son doba and began his travels when he was barely sixteen and successor William I, called the Bad (r. 1154-66), but years old with a visit to Asia Minor. Then he traveled toward the end of his life he returned to North Africa, along the southern coast of France, visited England, and and he died in 560/1165, probably in Ceuta.7 traveled widely in Spain and Morocco.2 Sometime about 1138, he was invited by the Norman king of Sicily, Roger AL-SHARIF AL-IDRISI AS A MAPMAKER II (A.D. 1097-1154), to Roger's court in Palermo, osten sibly to protect al-IdrisI from his enemies, but in fact so Of the two cartographic schools developed during the Roger could use the scholar's noble descent to further early period-the Ptolemaic and the Balkhi-al-Idrisl fol his own political objectives.3 Lewicki has put forward lowed the former. -

Lesson 4B OVERVIEW Explaining Relationships in Historical Texts

LESSON Lesson 4b OVERVIEW Explaining Relationships in Historical Texts Lesson Objectives LearningLearning Progression Progression Explain the relationships or interactions Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 between two or more individuals, events, [or] ideas . in a historical . text based Students explain events, Building on Grade 4, Grade 6 increases in on specific information in the text. ideas, or concepts in a students draw on specific complexity by requiring historical text, including details to explain the students to analyze in Reading what happened and why, relationships or interactions detail how a key individual, • Identify relationships and interactions based on specific among people, events, event, or idea is introduced, between two or more people, events, information in the text. ideas, or concepts in a illustrated, and elaborated ideas, or concepts in a historical text. historical text. in a text (e.g. through • Explain relationships and interactions examples or anecdotes). between two or more people, events, ideas, or concepts in a historical text. Writing • Draw evidence from informational texts to support analysis and reflection. Lesson Text Selections Speaking and Listening Modeled and Guided Instruction Guided Practice Independent Practice • Pose and respond to specific questions and contribute to discussions. Modeled and Guided Instruction Guided Practice Independent Practice Read Genre: History Article Read Genre: Eyewitness Account Read Genre: History Article T H E from WORDS TO KNOW R I S E • Review the key ideas expressed and Ancient A N D THREE As you read, look The History and Description of Africa inside, around, and F A L L Saharan Trade Routes beyond these words to by Leo Africanus O F by Joris Maddrin figure out what they AFRICAN Sahara Desert Tegaza mean. -

Discovery of Timbuktu: Geopolitical Rivalries and Myths Katherine Van Meter Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2012 Discovery of Timbuktu: Geopolitical Rivalries and Myths Katherine Van Meter Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation Van Meter, Katherine, "Discovery of Timbuktu: Geopolitical Rivalries and Myths" (2012). Honors Theses. 915. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/915 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Discovery of Timbuktu: Geopolitical Rivalries and Myths By Katherine C. Van Meter Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History Department of History Union College June, 2012 ABSTRACT Van Meter, Katherine Discovery of Timbuktu: Geopolitical Rivalries and Myths This thesis examines the exploration and discovery of Timbuktu primarily focusing on the travels and narrative of René Caillié the first European to publish his successful journey to Timbucku in 1828. Timbuktu since the thirteenth century had become a romantic mystery for Europeans and stimulated massive interest in its discovery by major geographical Societies. Through a mixture of primary and secondary sources I am able to analyze the geopolitical rivalries and myths surrounding Timbuktu that would instigate the travels of twenty-five English, fourteen Frenchmen, two Americans and one German which the majority of resulted in death.