Lalrotluanga 1 CHAPTER – 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Lunglei District

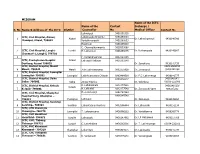

DISTRICT AGRICULTURE OFFICE LUNGLEI DISTRICT LUNGLEI 1. WEATHER CONDITION DISTRICT WISE RAINFALL ( IN MM) FOR THE YEAR 2010 NAME OF DISTRICT : LUNGLEI Sl.No Month 2010 ( in mm) Remarks 1 January - 2 February 0.10 3 March 81.66 4 April 80.90 5 May 271.50 6 June 509.85 7 July 443.50 8 August 552.25 9 September 516.70 10 October 375.50 11 November 0.50 12 December 67.33 Total 2899.79 2. CROP SITUATION FOR 3rd QUARTER KHARIF ASSESMENT Sl.No . Name of crops Year 2010-2011 Remarks Area(in Ha) Production(in MT) 1 CEREALS a) Paddy Jhum 4646 684716 b) Paddy WRC 472 761.5 Total : 5018 7609.1 2 MAIZE 1693 2871.5 3 TOPIOCA 38.5 519.1 4 PULSES a) Rice Bean 232 191.7 b) Arhar 19.2 21.3 c) Cowpea 222.9 455.3 d) F.Bean 10.8 13.9 Total : 485 682.2 5 OIL SEEDS a) Soyabean 238.5 228.1 b) Sesamum 296.8 143.5 c) Rape Mustard 50.3 31.5 Total : 585.6 403.1 6 COTTON 15 8.1 7 TOBACCO 54.2 41.1 8 SUGARCANE 77 242 9 POTATO 16.5 65 Total of Kharif 7982.8 14641.2 RABI PROSPECTS Sl.No. Name of crops Area covered Production Remarks in Ha expected(in MT) 1 PADDY a) Early 35 70 b) Late 31 62 Total : 66 132 2 MAIZE 64 148 3 PULSES a) Field Pea 41 47 b) Cowpea 192 532 4 OILSEEDS a) Mustard M-27 20 0.5 Total of Rabi 383 864 Grand Total of Kharif & Rabi 8365 15505.2 WATER HARVESTING STRUCTURE LAND DEVELOPMENT (WRC) HILL TERRACING PIGGERY POULTRY HORTICULTURE PLANTATION 3. -

Cultural Factors of Christianizing the Erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940)

Mizoram University Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences (A Bi-Annual Refereed Journal) Vol IV Issue 2, December 2018 ISSN: 2395-7352 eISSN:2581-6780 Cultural Factors of Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940) Zadingluaia Chinzah* Abstract Alexandrapore incident became a turning point in the history of the erstwhile Lushai Hills inhabited by simple hill people, living an egalitarian and communitarian life. The result of the encounter between two diverse and dissimilar cultures that were contrary to their form of living and thinking in every way imaginable resulted in the political annexation of the erstwhile Lushai Hills by the British colonial power,which was soon followed by the arrival of missionaries. In consolidating their hegemony and imperial designs, the missionaries were tools through which the hill tribes were to be pacified from raiding British territories. In the long run, this encounter resulted in the emergence and escalation of Christianity in such a massive scale that the hill tribes with their primal religious practices were converted into a westernised reli- gion. The paper problematizes claims for factors that led to the rise of Christianity by various Mizo Church historians, inclusive of the early generations and the emerging church historians. Most of these historians believed that waves of Revivalism was the major factor in Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills though their perspectives or approach to their presumptions are different. Hence, the paper hypothesizes that cultural factors were integral to the rise and growth of Christianity in the erstwhile Lushai Hills during 1890-1940 as against the claims made before. Keywords : ‘Cultural Factors of Conversion,’ Tlawmngaihna, Thangchhuah, Pialral, Revivals. -

Upa Exam Result 2012

BAPTIST CHURCH OF MIZORAM KOHHRAN UPA EXAM RESULT - 2012 LUNGLEI AREA Bial Sl.No. Hming Kohhran Grade Bazar 1 V.Lalremsanga Edenthar A Bazar 2 R.Lalrochama Kikawn A Bazar 3 K.Laltanpuia Kikawn B Bazar 4 Dr. Vansanglura Bazar B Bungtlang 5 F.Aihnuna Keitum B Bungtlang 6 Lalhmingliana Keitum B Chanmari 7 Vanneia Hnamte Chanmari A Chanmari 8 P.C.Lawmsanga Chanmari A Chanmari 9 F.Lalsawmliana Chanmari A Chawngte 10 Darrothanga Shalom A Chawngte 11 V.Biakengliana Kamalanagar A Chawngte 12 L.H.Ramthangliana Kinagar A Cherhlun 13 B.Lalsangzuala Cherhlun B Chhipphir 14 R.Lalhmachhuana Lungmawi B Chhipphir 15 C.Lalbiakthanga Chhipphir A Chhipphir 16 B.Lalbiakthanga Zote S A Electric 17 C.Lalrammawia Electric Veng A Electric 18 C.Siamkunga Electric Veng A Electric 19 P.C.Vanlalhluna Gosen B Electric 20 L.H.Biakliana Gosen A Electric 21 K.Lianzela Farmveng A Electric 22 R.Sangliana Farmveng A Electric 23 H.Lalnuntluanga Farmveng A Electric 24 J.Thanghmingliana Chanmari Vengthlang A Electric 25 B.Lalthlamuana Chanmari Vengthlang A Electric 26 P.C.Laltlanthanga Chanmari Vengthlang A Haulawng 27 Kawlrothanga Lamthuamthum B Hnahthial N 28 J.Lalchhanhimi Bazar A Hnahthial N 29 C.Lalthanpuia Bazar A Hnahthial N 30 F.Lalduhawma Thiltlang A Hnahthial N 31 L.C.Lalzara Thiltlang B Hnahthial N 32 Lalchhandama Bethel B Hnahthial S 33 H.Thansanga Rotlang E B Hnahthial S 34 V.Laldinthanga Rotlang E A Hnahthial S 35 K.Lalbiakkima Leite B Hrangchalkawn 36 S.V.L.Lawmawma Thualthu A Hrangchalkawn 37 T.Lalnghilhlova Thualthu A Lungchem 38 H.Sangliantluanga Kalvari Changpui A BAPTIST CHURCH OF MIZORAM KOHHRAN UPA EXAM RESULT - 2012 Bial Sl.No. -

The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram

================================================================= Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 15:5 May 2015 ================================================================= The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram Lalsangpuii, M.A. (English), B.Ed. ================================================================= Abstract This paper discusses the problems of English Language Teaching and Learning in Mizoram, a state in India’s North-Eastern region. Since the State is evolving to be a monolingual state, more and more people tend to use only the local language, although skill in English language use is very highly valued by the people. Problems faced by both the teachers and the students are listed. Deficiencies in the syllabus as well as the textbooks are also pointed out. Some methods to improve the skills of both the teachers and students are suggested. Key words: English language teaching and learning, Mizoram schools, problems faced by students and teachers. 1. Introduction In order to understand the conditions and problems of teaching-learning English in Mizoram, it is important to delve into the background of Mizoram - its geographical location, the origin of the people (Mizo), the languages of the people, and the various cultures and customs practised by the people. How and when English Language Teaching (ELT) was started in Mizoram or how English is perceived, studied, seen and appreciated in Mizoram is an interesting question. Its remoteness and location also create problems for the learners. 2. Geographical Location Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 15:5 May 2015 Lalsangpuii, M.A. (English), B.Ed. The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram 173 Figure 1 : Map of Mizoram Mizoram is a mountainous region which became the 23rd State of the Indian Union in February, 1987. -

Beyond Labor History's Comfort Zone? Labor Regimes in Northeast

Chapter 9 Beyond Labor History’s Comfort Zone? Labor Regimes in Northeast India, from the Nineteenth to the Twenty-First Century Willem van Schendel 1 Introduction What is global labor history about? The turn toward a world-historical under- standing of labor relations has upset the traditional toolbox of labor histori- ans. Conventional concepts turn out to be insufficient to grasp the dizzying array and transmutations of labor relations beyond the North Atlantic region and the industrial world. Attempts to force these historical complexities into a conceptual straitjacket based on methodological nationalism and Eurocentric schemas typically fail.1 A truly “global” labor history needs to feel its way toward new perspectives and concepts. In his Workers of the World (2008), Marcel van der Linden pro- vides us with an excellent account of the theoretical and methodological chal- lenges ahead. He makes it very clear that labor historians need to leave their comfort zone. The task at hand is not to retreat into a further tightening of the theoretical rigging: “we should resist the temptation of an ‘empirically empty Grand Theory’ (to borrow C. Wright Mills’s expression); instead, we need to de- rive more accurate typologies from careful empirical study of labor relations.”2 This requires us to place “all historical processes in a larger context, no matter how geographically ‘small’ these processes are.”3 This chapter seeks to contribute to a more globalized labor history by con- sidering such “small” labor processes in a mountainous region of Asia. My aim is to show how these processes challenge us to explore beyond the comfort zone of “labor history,” and perhaps even beyond that of “global labor history” * International Institute of Social History and University of Amsterdam. -

MIZORAM S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Name Of

MIZORAM Name of the ICTC Name of the Contact Incharge / S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Counsellor No Medical Officer Contact No Lalhriatpuii 9436192315 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Aizawl, Lalbiakzuala Khiangte 9856450813 1 Aizawl Dr. Lalhmingmawii 9436140396 Dawrpui, Aizawl, 796001 Vanlalhmangaihi 9436380833 Hauhnuni 9436199610 C. Chawngthanmawia 9615593068 2 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Lunglei Lunglei H. Lalnunpuii 9436159875 Dr. Rothangpuia 9436146067 Chanmari-1, Lunglei, 796701 3 F. Vanlalchhanhimi 9612323306 ICTC, Presbyterian Hospital Aizawl Lalrozuali Rokhum 9436383340 Durtlang, Aizawl 796025 Dr. Sanghluna 9436141739 ICTC, District Hospital, Mamit 0389-2565393 4 Mamit- 796441 Mamit John Lalmuanawma 9862355928 Dr. Zosangpuii /9436141094 ICTC, District Hospital, Lawngtlai 5 Lawngtlai- 796891 Lawngtlai Lalchhuanvawra Chinzah 9863464519 Dr. P.C. Lalramenga 9436141777 ICTC, District Hospital, Saiha 9436378247 9436148247/ 6 Saiha- 796901 Saiha Zingia Hlychho Dr. Vabeilysa 03835-222006 ICTC, District Hospital, Kolasib R. Lalhmunliani 9612177649 9436141929/ Kolasib 7 Kolasib- 796081 H. Lalthafeli 9612177548 Dr. Zorinsangi Varte 986387282 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Champhai H. Zonunsangi 9862787484 Hospital Veng, Champhai – 9436145548 8 796321 Champhai Lalhlupuii Dr. Zatluanga 9436145254 ICTC, District Hospital, Serchhip 9 Serchhip– 796181 Serchhip Lalnuntluangi Renthlei 9863398484 Dr. Lalbiakdiki 9436151136 ICTC, CHC Chawngte 10 Chawngte– 796770 Lawngtlai T. Lalengmuana 9436966222 Dr. Vanlallawma 9436360778 ICTC, CHC Hnahthial 11 Hnahthial– 796571 -

Town Survey Report Lunglei, Part XB, Series-31, Mizoram

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 PART-XB SERIES 31 MIZORAM TOWN SURVEY REPORT LUNGLEI B.SATYANARAYANA Deputy Director Directorate of Census Operations MIZORAM ~J.a. LIST OF MAps AND PHOTOGRAPHS (ii) FOREWORD (iii) .. PREFACE . (v)-(vi) NOTIONAL MAP OF LUNGLBI TOWN (vii) CHAPTER I Introduction • 1-8 IlHAPlER II History and Growth of the TOWB 9-11 CHAPTER III Amenities and Services-History of Growth and the Present Positi"n • 12-1k CHAPTER IV Economic Life of the Town 19-34. CHAPTER V Ethnic and Selected Socio-Demograpkic C.laara~tori8tici oftke PopulatioR 35-42 CHAPTER VI Migration and Settlement of Families • 43-51 CHAPTER VII Neighbourhood Pattern • 54-56 CHAPTER vm Family Life in the Tows • • • CHAPTER IX Housing and Material Culture • • 63-72 CHAPTER X Slums, Blighted and other Areas with Sub-standard Living Conditions. 73 CHAPTER XI Organisation of Power and Prestige • • 74-82 CHAPTER XII Leisure and Recreation, Social ParticipatioJl, Social Awareness, Religion and Crime • 83-93 OHAPTER XIII Linkages and ContiJl1la • • • • 94-98 CONOLUSION • • • • 99-100 6LOSSARY • 101 LIST OF MAPS'·~ PMOrOGRAPHS Facing Page . , , Notional Map of Lunglei town (vii) Baptist Church Serkawn 4 Stteet (one of the business streets of Lunglei Town) ". '. 5 B.s Station (MST) 6 Memorial Stone erected for the memory of the first Baptist Church founded in Mizoram 7, T~ First Ba.ptist Church BuHdingin Mjz()ralp .. .. " ... " 8 Stone Bridge over Sipai Lui ~O Circuit House 11 Post Office ' 1~ Government High School " 16 Government College 16 Serkawn Christian High School 17'1 Civil Hospital 18 Christian Hospital Serkawn 19<' R;'f.P. -

The Mizoram Gazette EXTRA ORDINARY Published by Authority RNI No

The Mizoram Gazette EXTRA ORDINARY Published by Authority RNI No. 27009/1973 Postal Regn. No. NE-313(MZ) 2006-2008 VOL - XLVIII Aizawl, Thursday 10.1.2019 Pausha 20, S.E. 1940, Issue No. 7 NOTIFICATION List of live Medical Practitioners registered under Mizoram State Medical Council as on 31.12.18 Sl. Registration Name Date of Qualification Address No. Number Birth 1. MSMC/2017/395 Abraham Lalchhana 23.12.1980 MBBS MD B/19, Chawnpui Chhawnchhim (Anaesthesiology) Aizawl, Mizoram 2. MSMC/2018/571 Albert Lalhminghlua 14.07.1982 MBBS Mualpui Veng Chhingchhip, Mizoram 3. MSMC/2018/640 Albert Lalhmunsanga 02.12.1991 MBBS K/110 Tlangnuam Vengthar Aizawl, Mizoram 4. MSMC/2018/669 Aldy Lalruatpuia 01.04.1986 MBBS G/75, Khatla East Aizawl, Mizoram 5. MSMC/2018/460 Andrew Khawlthangpuia 23.06.1983 MBBS H. No. / 43, Siaha Ramlawt Tlangkawn III Siaha, Mizoram 6. MSMC/2017/276 Andrew Lalramliana 19.01.1989 MBBS Chhingchhip Venghlun Serchhip Dist., Mizoram 7. MSMC/2017/303 B Laldinliana 05.11.1963 MBBSMS Christian Hospital, Serkawn (General Surgery) Lunglei, Mizoram 8. MSMC/2017/370 B Lalnunthari 23.12.1974 MBBS Bawngkawn South Diploma in Pathology Aizawl, Mizoram & Bacteriology 9. MSMC/2018/562 B Lalramzauva 04.04.1955 MBBSMD D/26, Zarkawt (Obs & Gynae) Aizawl, Mizoram 10. MSMC/2018/081 B Lalrinzauvi 11.05.1974 MBBS Serkawn Lunglei, Mizoram 11. MSMC/2018/589 B Lalthantluanga 08.09.1982 MBBS C/33, Ramthar North Aizawl, Mizoram 12. MSMC/2018/429 B Zonunsanga 20.09.1984 MBBSMS H. No. / 75, Chandmary (Gen. Surgery) Lawngtlai, Mizoram 13. -

Program of Study the Earliest Christian Missionaries to Mizoram, the State at the Southernmost Tip of India's Easternmost Fron

Program of Study The earliest Christian missionaries to Mizoram, the state at the southernmost tip of India’s easternmost frontier, are today regional heroes. Stone memorials of their visits rise up along roadsides, their portraits hang above hospital rooms, their hair clippings are preserved behind glass. Even schoolchildren’s sports teams are named in their honour. Histories of Mizoram place these British missionaries and administrators in the foreground, while Mizos remain two-dimensional stock characters in the background. This project aims not to follow the British missionaries of the mid-1890s but rather to face them, and to turn towards the Mizo as a corrective to our usual, British perspective on Mizoram’s contact with Christianity. The introduction to Mizoram of Western biomedicine features prominently in the writings of early missionaries. However, Mizo responses to it, whether as a technology of health or as a missionary tool of salvation, have not yet been investigated. Unlike the usual focus on religious ‘worldviews’, medicine provides us with a limited and concrete case study, but one just as intensely wrapped up in religiosity, both Christian and Mizo. As historian David Hardiman notes, mission medicine “was not carried out for a purely medical purpose, but used as a beneficent means to spread Christianity.”1 Indeed, in Mizoram it was at the missionaries’ medicine dispensary itself that the names of those wishing to become Christians were to be handed in.2 At the same time, author C. G. Verghese rightly points out that -

List of Empaneled Providers for Sterilization

State Mizoram Year 08.03.2021 Empanelment List for Minilap Providers Qualification Type of (MBBS/MS- facility Postal address of facility Name of Empanelled Contact S.No Name of district Gynae/DGO/DNB/MS- Designation posted where empanelled Sterilization Provider number Surgery/Other (PHC/CHC/ provider is posted Speciality SDH/DH) 1 Aizawl Dr. Hmingthanmawii MBBS SPO(RCH) Office CMO AIZAWL EAST 9436154624 2 Aizawl Dr. Lalthlengliani MD (Biochem) SNO Office Project Director MSACS 9436142265 3 Aizawl Dr. Zonunsiama Pathology PO (CEA) Office H&FW, Dinthar, Aizawl 9436151903 4 Aizawl Dr. Lalramliana MBBS DD (Gen) Office H&FW, Dinthar, Aizawl 9436158041 5 Aizawl Dr. Lalchhuanawma MPH SNO Office NHM, Dinthar 9862787705 6 Aizawl Dr. David Zothansanga MBBS SNO NUHM H&FW, Dinthar, Aizawl 9436195627 7 Aizawl Dr. Pachuau Lalmalsawma MPH PO (IDSP) Office NHM, Dinthar 9436195535 Consultant (Training & 8 Aizawl Dr. Zorinsangi MPH planning) Office H&FW, Dinthar, Aizawl 9677019522 9 Aizawl Dr. C. Vankhuma PSM Consultant Office ZMC Falkawn 9612345948 10 Aizawl Dr. Vanlalhruaii MD (Pharma) Consultant Office H&FW, Dinthar, Aizawl 9436153297 11 Aizawl Dr. Lalnuntluangi MBBS PO (Statistics) Office DHS, H&FW, Dinthar 9615432021 12 Aizawl Dr. Esther Lalrammawii MBBS Consultant Office ZMC FALKAWN 9862541485 13 Aizawl Dr. Biakthansangi MPH Dy. CEO Office MSHCS, NHM, Dinthar 9436152356 14 Aizawl Dr. Lalzepuii MBBS CMO Office H&FW, Dinthar, Aizawl 9868220014 15 Aizawl Dr. Lalparliani MBBS SMO Office H&FW, Dinthar, Aizawl 9862257999 16 Aizawl Dr. Lalrinmuani Sailo MS (Surgery) Consultant DH Civil Hospital Lunglei 8730097619 17 Aizawl Dr. F Lalthakimi MD (Anaes) MO DH Civil Hospital Aizawl 9436146337 18 Aizawl Dr. -

F:\BHSS\Letter Head A4.Pmd

OFFICE OF THE PRINCIPAL, BAPTIST HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, SERKAWN PIN - 796691. DIST - LUNGLEI; MIZORAM Registered under the Mizoram Societies Ast, 2005 (Act No. 13 of 2005) Regn. No. MSR 1257 of 24.02.2021 & Affiliated to MBSE. Regn. No. MBSE.LLI/HSS/01 Dated 20.10.1998 website: https://baptisthss.in email: [email protected] Motto: The Utmost for the Highest Dated: Lunglei 10th June, 2021 Dt 9th June, 2021 ah Class XI First phase Application Form scrutinize a ni a. Diltu zingah dil phalo, an percentage chhut diklo leh cut off mark pha lo an awm zeuh zeuh a. Chutiang ho paih anih hnuah, stream hrang dil kawpte pakhat zawkah dah in, Class XI a first phase a admis- sion pek theih zat chu hetiang hi a ni. 1. XI Arts A - 50 2. XI Arts B - 59 3. XI Commerce - 51 4. XI Science A - 70 5. XI Science B - 64 Page 2-na atangin Baptist Higher Secondary School, Serkawn, Class XI Selected List 2021-2022 tarlan a ni. 1. XI Arts A - Page 2 - 3 2. XI Arts B - Page 3 - 4 3. XI Commerce - Page 4 - 5 4. XI Science A - Page 5 - 7 5. XI Science B - Page 7 - 8 HRIATTUR PAWIMAWH TE: 1. Ni 9th - 13th June, 2021 thleng admission tih theih a ni ang. 2. Huntiam chhunga Admission tilo chu 2nd Phase seat atan reserve an ni ang. 3. Student Code pek vek an ni a. Hemi hmang hian school website (a hnuaia link dah) ah admission tih tur a ni. 4. Student Code chhulut in student hming leh fee pek zat tur a lo lang ang. -

The List of Protected Monuments by Department of Art & Culture

ART & CULTURE DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF MIZORAM Archaeology Section Under-mentioned is the list of protected monuments by Department of Art & Culture under Section 3 of Mizoram Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 2001. 1. Ancient arts Chhawrtui, Champhai District 2. BakPuk Lungrang ‘S’, Lunglei District 3. BengkhuaiaThlan Sailam, Aizawl District 4. Bung Bungalow Tuirial, Aizawl District 5. Captain Brown-a Thlan Changsil Fort, Aizawl District 6. ChhuraLungkawh Sihfa, Aizawl District 7. Chief Saihleia Residence Samlukhai, Aizawl District 8. DullaiSial Hliappui, Champhai District 9. DurtlangLal In Durtlang, Aizawl District 10. FiaraTui Farkawn, Champhai District 11. HualtuNgamtawnaUi No neihna Hualtu, Serchhip District 12. Kawlkulh Bungalow Kawlkulh, ChamphaiDistirct 13. KhuangzangPuk&Mitdelhnuhthlakna Phuaibuang, Aizawl District 14. Kolasib Bungalow Kolasib, Kolasib District 15. Kumpinu Lung Saitual, Aizawl District 16. LalLalvungaThlan Sazep, Champhai District 17. LalLungdawh Phulpui, Aizawl District 18. Lalbengkhuaia& Sap Sa-UiTanna Serchhip, Serchhip District 19. Lalhrima Bung lehTuikhur Thenzawl, Serchhip District 20. LallulaHmun Samthang, Champhai District 21. LalnuRothluaiiThlan Leite, Lunglei District 22. Lalruanga Lung Khawbung, Champhai District 23. LalruangaLungkaih Suangpuilawn, Aizawl District 24. LamsialPuk Farkawn, Champhai District 25. LianchhiariLunglentlang Dungtlang, Champhai District 26. Lung hmainei Tawitlang, Aizawl District 27. Lungau Ruallung, Aizawl District 28. Lungkeiphawtial Farkawn, Champhai District 29. Lungkhawdur Vanchengpui, Champhai Dist. 30. Lungkhawsa Vaphai, Champhai District 31. LungphunLian Lungphunlian,Champhai Dist. 32. Mel venghmasaber Hualngohmun, Aizawl District 33. MeltlangPuk Thingsat, Aizawl District 34. Mission School Serkawn, LungleiDIstrict 35. Mura Puk Sialhawk, Aizawl District 36. Mura Puk Zote, Champhai District 37. NeihlaiateNupathlan Hmuifang, Aizawl District 38. Ngente Nu LunglenTlang Khawrihnim, Mamit District 39. North Vanlaiphai Dispensary N. Vanlaiphai, Champhai Dist.