Caribbean-Crossroads.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Family's Guide to Explore NYC for FREE with Your Cool Culture Pass

coolculture.org FAMILY2019-2020 GUIDE Your family’s guide to explore NYC for FREE with your Cool Culture Pass. Cool Culture | 2019-2020 Family Guide | coolculture.org WELCOME TO COOL CULTURE! Whether you are a returning family or brand new to Cool Culture, we welcome you to a new year of family fun, cultural exploration and creativity. As the Executive Director of Cool Culture, I am excited to have your family become a part of ours. Founded in 1999, Cool Culture is a non-profit organization with a mission to amplify the voices of families and strengthen the power of historically marginalized communities through engagement with art and culture, both within cultural institutions and beyond. To that end, we have partnered with your child’s school to give your family FREE admission to almost 90 New York City museums, historic societies, gardens and zoos. As your child’s first teacher and advocate, we hope you find this guide useful in adding to the joy, community, and culture that are part of your family traditions! Candice Anderson Executive Director Cool Culture 2020 Cool Culture | 2019-2020 Family Guide | coolculture.org HOW TO USE YOUR COOL CULTURE FAMILY PASS You + 4 = FREE Extras Are Extra Up to 5 people, including you, will be The Family Pass covers general admission. granted free admission with a Cool Culture You may need to pay extra fees for special Family Pass to approximately 90 museums, exhibits and activities. Please call the $ $ zoos and historic sites. museum if you’re unsure. $ More than 5 people total? Be prepared to It’s For Families pay additional admission fees. -

El Museo Del Barrio 50Th Anniversary Gala Honoring Ella Fontanals-Cisneros, Raphael Montañez Ortíz, and Craig Robins

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE EL MUSEO DEL BARRIO 50TH ANNIVERSARY GALA HONORING ELLA FONTANALS-CISNEROS, RAPHAEL MONTAÑEZ ORTÍZ, AND CRAIG ROBINS For images, click here and here New York, NY, May 5, 2019 - New York Mayor Bill de Blasio proclaimed from the stage of the Plaza Hotel 'Dia de El Museo del Barrio' at El Museo's 50th anniversary celebration, May 2, 2019. "The creation of El Museo is one of the moments where history started to change," said the Mayor as he presented an official proclamation from the City. This was only one of the surprises in a Gala evening that honored Ella Fontanals-Cisneros, Craig Robins, and El Museo's founding director, artist Raphael Montañez Ortiz and raised in excess of $1.2 million. El Museo board chair Maria Eugenia Maury opened the evening with spirited remarks invoking Latina activist Dolores Huerta who said, "Walk the streets with us into history. Get off the sidewalk." The evening was MC'd by WNBC Correspondent Lynda Baquero with nearly 500 guests dancing in black tie. Executive director Patrick Charpenel expressed the feelings of many when he shared, "El Museo del Barrio is a museum created by and for the community in response to the cultural marginalization faced by Puerto Ricans in New York...Today, issues of representation and social justice remain central to Latinos in this country." 1230 Fifth Avenue 212.831.7272 New York, NY 10029 www.elmuseo.org Artist Rirkrit Travanija introduced longtime supporter Craig Robins who received the Outstanding Patron of Art and Design Award. Craig graciously shared, "The growth and impact of this museum is nothing short of extraordinary." El Museo chairman emeritus and artist, Tony Bechara, introduced Ella Fontanals-Cisneros who received the Outstanding Patron of the Arts award, noting her longtime support of Latin artists including early support Carmen Herrera, both thru acquiring her work and presenting it at her Miami institution, Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO). -

Around Town 2015 Annual Conference & Meeting Saturday, May 9 – Tuesday, May 12 in & Around, NYC

2015 NEW YORK Association of Art Museum Curators 14th Annual Conference & Meeting May 9 – 12, 2015 Around Town 2015 Annual Conference & Meeting Saturday, May 9 – Tuesday, May 12 In & Around, NYC In addition to the more well known spots, such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, , Smithsonian Design Museum, Hewitt, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, The Frick Collection, The Morgan Library and Museum, New-York Historical Society, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, here is a list of some other points of interest in the five boroughs and Newark, New Jersey area. Museums: Manhattan Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021 (212) 288-6400 http://asiasociety.org/new-york Across the Fields of arts, business, culture, education, and policy, the Society provides insight and promotes mutual understanding among peoples, leaders and institutions oF Asia and United States in a global context. Bard Graduate Center Gallery 18 West 86th Street New York, NY 10024 (212) 501-3023 http://www.bgc.bard.edu/ Bard Graduate Center Gallery exhibitions explore new ways oF thinking about decorative arts, design history, and material culture. The Cloisters Museum and Garden 99 Margaret Corbin Drive, Fort Tyron Park New York, NY 10040 (212) 923-3700 http://www.metmuseum.org/visit/visit-the-cloisters The Cloisters museum and gardens is a branch oF the Metropolitan Museum oF Art devoted to the art and architecture oF medieval Europe and was assembled From architectural elements, both domestic and religious, that largely date from the twelfth through fifteenth century. El Museo del Barrio 1230 FiFth Avenue New York, NY 10029 (212) 831-7272 http://www.elmuseo.org/ El Museo del Barrio is New York’s leading Latino cultural institution and welcomes visitors of all backgrounds to discover the artistic landscape of Puerto Rican, Caribbean, and Latin American cultures. -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

NEWSLETTER Information Exchange in the Caribbean July 2012 MAC AGM 2012

ISSUE 8 NEWSLETTER Information Exchange in the Caribbean July 2012 MAC AGM 2012 Plans are moving ahead for the 2012 MAC AGM which is to be held in Trinidad, October 21st-24th. For further information please regularly visit the MAC website. Over the last 6 months whilst compiling articles for the newsletter one positive thing that has struck the Secretariat is the increase in the promotion Inside This Issue of information exchange in the Caribbean region. The newsletter has covered a range of conferences occurring this year throughout the Caribbean and 2. Caribbean: Crossroads of several new publications on curatorship in the Caribbean will have been the World Exhibition released by the end of 2012. 3. World Heritage Inscription Ceremony in Barbados Museums and museum staff should make the most of these conferences and 4. Zoology Inspired Art see them not only as a forum to learn about new practices but also as a way 5. 2012 MAC AGM to meet colleagues, not necessarily just in the field of museum work but also 6. New Book Released in many other disciplines. In the present financial situation the world finds ´&XUDWLQJLQWKH&DULEEHDQµ 7. Sint Marteen National itself, it may sound odd to be promoting attendance at conferences and Heritage Foundation buying books but museums must promote continued professional 8. ICOM Advisory Committee development of their staff - if not they will stagnate and the museum will Meeting suffer. 9. Membership Form 10. Association of Caribbean MAC is of course aware that the financial constraints facing many museums at Historians Conference present may limit the physical attendance at conferences. -

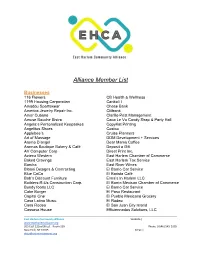

Alliance Member List

Alliance Member List Businesses 116 Flowers CB Health & Wellness 1199 Housing Corporation Cenkali I Amadou Sportswear Chase Bank America Jewelry Repair Inc. Citibank Amor Cubano Clarillo Pest Management Amuse Bauche Bistro Coco Le Vu Candy Shop & Party Hall Angela;s Personalized Keepsakes CopyKat Printing Angelitos Shoes Costco Applebee’s Cruise Planners Art of Massage DDM Development + Services Aroma D’angel Dear Mama Coffee Aromas Boutique Bakery & Café Deposit a Gift AV Computer Corp Direct Print Inc. Azteca Western East Harlem Chamber of Commerce Baked Cravings East Harlem Tax Service Barcha East River Wines Blooni Designs & Contracting El Barrio Car Service Blue CoCo El Barista Café Bob’s Discount Furniture Elma’s In Harlem LLC Builders-R-Us Construction Corp. El Barrio Mexican Chamber of Commerce Bundy foods LLC El Barrio Car Service Cake Burger El Paso Restaurant Capital One El Pueblo Mexicano Grocery Casa Latina Music El Rodeo Casa Rodeo El San Juan City Island Cassava House Efficiennados Solutions, LLC East Harlem Community Alliance Website | www.eastharlemalliance.org 205 East 122nd Street - Room 220 Phone | (646) 545-5205 New York, NY 10035 Email | [email protected] Euromex Soccer Play Up Studio Evelyn’s Kitchen Plaza Mexico Event by Debbie King Ponce Bank Fierce Nail Spa Salon Popular Bank GinJan Bros LLC Rancho Vegado Inc. Harlem Shake Result Media Team Gotham To Go R&M Party Supply Store GM Pest Control Rancho Vegado Corp Heavy Metal Bike Shop The Roast NYC IHOP The Rosario Group JC-1 Graph-X Sabor Borinqueño La Costeñito Grocery Sam’s Pizzeria La Reina Del Barrio Inc. -

Almanaque Marc Emery. June, 2009

CONTENIDOS 2CÁLCULOS ASTRONÓMICOS PARA LOS PRESOS POLÍTICOS PUERTORRIQUEÑOS EN EL AÑO 2009. Jan Susler. 6ENERO. 11 LAS FASES DE LA LUNA EN LA AGRICULTURA TRADICIONAL. José Rivera Rojas. 15 FEBRERO. 19ALIMÉNTATE CON NUESTROS SUPER ALIMENTOS SILVESTRES. María Benedetti. 25MARZO. 30EL SUEÑO DE DON PACO.Minga de Cielos. 37 ABRIL. 42EXTRACTO DE SON CIMARRÓN POR ADOLFINA VILLANUEVA. Edwin Reyes. 46PREDICCIONES Y CONSEJOS. Elsie La Gitana. 49MAYO. 53PUERTO RICO: PARAÍSO TROPICAL DE LOS TRANSGÉNICOS. Carmelo Ruiz Marrero. 57JUNIO. 62PLAZA LAS AMÉRICAS: ENSAMBLAJE DE IMÁGENES EN EL TIEMPO. Javier Román. 69JULIO. 74MACHUCA Y EL MAR. Dulce Yanomamo. 84LISTADO DE ORGANIZACIONES AMBIENTALES EN PUERTO RICO. 87AGOSTO. 1 92SOBRE LA PARTERÍA. ENTREVISTA A VANESSA CALDARI. Carolina Caycedo. 101SEPTIEMBRE. 105USANDO LAS PLANTAS Y LA NATURALEZA PARA POTENCIAR LA REVOLUCIÓN CONSCIENTE DEL PUEBLO.Marc Emery. 110OCTUBRE. 114LA GRAN MENTIRA. ENTREVISTA AL MOVIMIENTO INDÍGENA JÍBARO BORICUA.Canela Romero. 126NOVIEMBRE. 131MAPA CULTURAL DE 81 SOCIEDADES. Inglehart y Welzel. 132INFORMACIÓN Y ESTADÍSTICAS GENERALES DE PUERTO RICO. 136DICIEMBRE. 141LISTADO DE FERIAS, FESTIVALES, FIESTAS, BIENALES Y EVENTOS CULTURALES Y FOLKLÓRICOS EN PUERTO RICO Y EL MUNDO. 145CALENDARIO LUNAR Y DÍAS FESTIVOS PARA PUERTO RICO. 146ÍNDICE DE IMÁGENES. 148MAPA DE PUERTO RICO EN BLANCO PARA ANOTACIONES. 2 3 CÁLCULOS ASTRONÓMICOS PARA LOS PRESOS Febrero: Memorias torrenciales inundarán la isla en el primer aniversario de la captura de POLÍTICOS PUERTORRIQUEÑOS EN EL AÑO 2009 Avelino González Claudio, y en el tercer aniversario de que el FBI allanara los hogares y oficinas de independentistas y agrediera a periodistas que cubrían los eventos. Preparado por Jan Susler exclusivamente para el Almanaque Marc Emery ___________________________________________________________________ Marzo: Se predice lluvias de cartas en apoyo a la petición de libertad bajo palabra por parte de Carlos Alberto Torres. -

PUERTO RICO ARTE E IDENTIDAD ENSAYOS-TRASFONDO HISTORICO SOBRE LA Epoca

PUERTO RICO ARTE E IDENTIDAD ENSAYOS-TRASFONDO HISTORICO SOBRE LA EpOCA. LAPATRIA CRIOLLA SILVIA ALVAREZ CURVELO A 10 largo del siglo XIX, Puerto Rico gener6, en un denso entre-juego de fuerzas internas y externas, los contornos de una identidad nacional. Esta trama complicada requiri6 de transformaciones en entretejido de la sociedad. La Jlegada de miles de esclavos africanos para trabajar las promisorias haciendas azucareras y el arriba de otros miles de inmigrantes provenientes de Europa, Hispanoarnerica y las AntiJlas Menores, se tradujo en la textura plural que exhiben los puertorriqueiios hoy. Durante el siglo concluy6 tambien la ocupacion del territorio insular. La montana fue conquistada por avidos pobladores que roturaron I la tierra y empresarios que la comercializaron en el fomento de una nueva cuilura agraria: la del cafe. Nuevas identidades --el hacendado criollo, el comerciante peninsular, los jornaleros, los esclavos libertos, los obreros de fin de siglo, los intelectuales- emitieron, desde sus particulares estaciones de vida y visiones de mundo, utopias para sus comunidades y el pais. Alentados por los cambios geopoliticos y econ6micos que propici6 el cicio revolucionario, 1776-1825. los criollos pucrtorriquciios se movilizaron a favor de mayores libertades desde las primeras decadas del siglo. Mientras Espaiia enfrentaba las fuerzas francesas de ocupaci6n y la mayoria de sus colonias en America proclamaban su independencia, Puerto Rico marcaba un derrotero distinto. La Isla no se sum6 a Ia revoluci6n hispanoamericana de independencia que estall6 en 1810, pero personeros criollos como Ram6n Power y Giralt, primer diputado puertorriqueiio a las Cortes espaiiolas, respaldaron demandas de indiscutible corte liberal. -

PRESS RELEASE the Heerlen Rooftop Project: an Ambitious Architecture Competition

PRESS RELEASE Heerlen, 18 July 2019 The Heerlen Rooftop Project: an ambitious architecture competition. SCHUNCK announces an international urban design idea competition for an urban rooftop project in the heart of the city of Heerlen (NL). The city centre of Heerlen is characterized by a dense and diverse urban rooftop landscape. Large grey and sterile roof surfaces dominate the view from above. SCHUNCK and Heerlen aim to explore this unused surface potential for gardening, arts, farming, cultural festivals, music, cinema, coffee houses, sports, tiny housing and much more. Rooftop projects in cities across the globe prove that gardens, art, recreation and/or business activity can turn ugly sterile spaces into something special. To start a transformation, SCHUNCK invites architects, urban planners, landscape architects and designers to participate in this international competition. The participants are asked to submit their design ideas for the city-centre rooftops in Heerlen to make these rooftops accessible and sustainable. More competition information on: https://schunck.nl/en/rooftop-competition/ The deadline for registration is: 25 August 2019 About The Heerlen Rooftop Project The concept for The Heerlen Rooftop Project has two principal action lines: • stimulate owners in the city centre of Heerlen to make their own rooftops accessible and sustainable. • initiate and co-organize recurring Rooftop Festivals with the municipality of Heerlen and multiple, cultural partners to encourage (local) stakeholders, participants, entrepreneurs -

S. Price Patchwork History : Tracing Artworlds in the African Diaspora Essay on Interpretations of Visual Art in Societies of the African Diaspora

S. Price Patchwork history : tracing artworlds in the African diaspora Essay on interpretations of visual art in societies of the African diaspora. Author relates this to recent shifts in anthropology and art history/criticism toward an increasing combining of art and anthropology and integration of art with social and cultural developments, and the impact of these shifts on Afro-American studies. To exemplify this, she focuses on clothing (among Maroons in the Guianas), quilts, and gallery art. She emphasizes the role of developments in America in these fabrics, apart from just the African origins. In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 75 (2001), no: 1/2, Leiden, 5-34 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl SALLY PRICE PATCHWORK HISTORY: TRACING ARTWORLDS IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA This paper considers interpretations of visual art in societies of the African diaspora, setting them within the context of recent theoretical shifts in the dis- ciplines of anthropology and art history/criticism. I will be arguing for the relevance to Afro-American studies of these broader disciplinary changes, which have fundamentally reoriented scholarship on arts that, for the most part, fall outside of what Joseph Alsop (1982) has dubbed "The Great Tradi- tions." Toward that end, I begin with a general assessment of these theoretical shifts (Part 1: Anthropology and Art History Shake Hands) before moving into an exploration of their impact on Afro-American studies (Part 2: Mapping the African-American Artworld). I then -

View Exhibition Brochure

1 Renée Cox (Jamaica, 1960; lives & works in New York) “Redcoat,” from Queen Nanny of the Maroons series, 2004 Color digital inket print on watercolor paper, AP 1, 76 x 44 in. (193 x 111.8 cm) Courtesy of the artist Caribbean: Crossroads of the World, organized This exhibition is organized into six themes by El Museo del Barrio in collaboration with the that consider the objects from various cultural, Queens Museum of Art and The Studio Museum in geographic, historical and visual standpoints: Harlem, explores the complexity of the Caribbean Shades of History, Land of the Outlaw, Patriot region, from the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) to Acts, Counterpoints, Kingdoms of this World and the present. The culmination of nearly a decade Fluid Motions. of collaborative research and scholarship, this exhibition gathers objects that highlight more than At The Studio Museum in Harlem, Shades of two hundred years of history, art and visual culture History explores how artists have perceived from the Caribbean basin and its diaspora. the significance of race and its relevance to the social development, history and culture of the Caribbean: Crossroads engages the rich history of Caribbean, beginning with the pivotal Haitian the Caribbean and its transatlantic cultures. The Revolution. Land of the Outlaw features works broad range of themes examined in this multi- of art that examine dual perceptions of the venue project draws attention to diverse views Caribbean—as both a utopic place of pleasure and of the contemporary Caribbean, and sheds new a land of lawlessness—and investigate historical light on the encounters and exchanges among and contemporary interpretations of the “outlaw.” the countries and territories comprising the New World. -

MAGALI REUS *1981, Den Haag, NL Lives in London, UK

MAGALI REUS *1981, Den Haag, NL Lives in London, UK www.magalireus.com Education Depuis 1788 2006 - 2008 MFA Fine Art, Goldsmiths College, London, UK 2002 - 2005 BA (Hons) Fine Art, Goldsmiths College, London, UK Freymond-Guth Fine Arts 2001 - 2002 Foundation Art and Design, Gerrit Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam, Limmatstrasse 270 NL CH 8005 Zürich T +41 (0)44 240 0481 offi[email protected] www.freymondguth.com Tue – Fri 11 – 18h Solo Shows (selection) Saturday 11 – 17h Or by appointment 2015 The Hepworth Wakefield, UK Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin, IT Sculpture Centre, New York, USA 2014 The Approach, London, UK Circuit, Lausanne, CH 2013 Highly Liquid, Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam, NL Out of Empty, Albert Baronian Project Space, Brussels, BE 2012 BB #7: Magali Reus, BLACKBOARD at SPACE studios, London, UK Unsolo project room (1/9unosunove), Milan, IT 2011 ON, The Approach, London, UK 2010 Weekend, Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam, NL Background, IBID Projects, London, UK 2009 Background, La Salle de bains, Lyon, FR Some Surplus, Plan B Projects, Amsterdam, NL 2008 The Angle Between Two Walls, (with Brock Enright), MOT International, London, UK 2006 Playstation: A Billion Balconies Facing the Sun, Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam, NL Group Shows (selection) 2014 Monumental Fatigue, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, CH Frieze London, with Freymond-Guth Fine Arts Nature after Nature, Kunsthalle Fridericianum, Kassel DE To Meggy Weiss Lo Surdo, Happy Hours, CO2, Torino, IT Superficial Hygiene, De Hallen, Haarlem, NL Pool, Kestnergesellschaft, Hannover, DE Post/Post Minimal, Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, CH Andrea Rosen, New York, USA 2013 Rijksakademie Open, Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten, Amsterdam, NL Silent Hardware, David Dale Gallery, Glasgow, GB Slip, The Approach, London, UK Shadows of a Doubt’, Tallinn Art Hall, Tallinn, ES, cur.