A Walk in Taylor Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geochemical Evidence for the Origin of Mirabilite Deposits Near Hobbs Glacier, Victoria Land, Antarctica

Mineral. Soc. Amer. Spec. Pap. 3, 261-272 (1970). GEOCHEMICAL EVIDENCE FOR THE ORIGIN OF MIRABILITE DEPOSITS NEAR HOBBS GLACIER, VICTORIA LAND, ANTARCTICA C. J. BOWSER, Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 T. A. RAFTER, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, Institute of Nuclear Studies, Lower Hutt, New Zealand R. F. BLACK, Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 ABSTRACT Numerous masses of bedded and concentrated interstitial mirabilite (Na,SO.·lOH,O) occur in stagnant glacial ice and within and on top of ice-cored moraine near the terminus of Hobbs Glacier on the west coast of McMurdo Sound. Some are tabular bodies up to 50 m long and 4 m thick. They are thought to be deposits formed by freeze concentration and evaporation in supraglacial and periglacial meltwater ponds. Some deposits have been included within ice and de- formed during glacial movement. Structural features within the ice and lithology of the morainal debris indicate the moraine is a remanent mass left during retreat of the formerly extended Koettlitz Glacier presently south of the Hobbs Glacier region. Compositionally the salt masses are predominantly sodium sulfate, although K, Ca, Mg, Cl, and HC0 are also 3 present, usually in amounts totalling less than five percent of the total salts. The mirabilite content of analyzed samples constitutes from 10to nearly 100percent of the total mass: the remainder is mostly ice. Isotopically the 8D and 8018composition of water of crystallization of entrapped glacial ice falls on Craig's (1961) line 18 for meteoric water (80 range -6.8°/00 to -37.9°/00' 8D-58.5°/00 to -30JD/00, relative to S.M.O.W.). -

DRAFT COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION (CEE) for ANDRILL Mcmurdo Sound Portfolio Madrid, 9/20 De Junio 2003

XXVI ATCM Working Paper WP-002-NZ Agenda Item: IV CEP 4a NEW ZEALAND Original: English DRAFT COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION (CEE) FOR ANDRILL McMurdo Sound Portfolio Madrid, 9/20 de junio 2003 ANDRILL - The McMurdo Sound Portfolio An international research effort with the participation of Germany, Italy, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. DRAFT COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION (CEE) FOR ANDRILL McMurdo Sound Portfolio Antarctica New Zealand Private Bag 4745, Christchurch Administration Building International Antarctic Centre 38 Orchard Road, Christchurch January 22, 2003 2 CONTENTS 1. NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY.....................................................................................11 2. INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................13 2.1 What is ANDRILL?...............................................................................................13 2.2 The CEE process.................................................................................................15 2.2.1 What is a CEE and why is it needed?....................................................15 2.2.2 Process for preparing the Draft CEE .....................................................15 3. DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED ACTIVITES ..............................................................17 2.1 Purpose and Need...............................................................................................17 3.1.1 Scientific justification..............................................................................17 -

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

Mcmurdo LTER: Glacier Mass Balances of Taylor Valley, Antarctica ANDREW G

Dana, G.L., C.M. Tate, and S.L. Dewey. 1994. McMurdo LTER: The use Moorhead, D.L., and R.A. Wharton, Jr. 1994. McMurdo LTER: Primary of narrow-band spectroradiometry to assess algal and moss com- production model of benthic microbial mats in Lake Hoare, munities in a dry valley stream. Antarctic Journal of the U.S., 29(5). Antarctica. Anta rctic Journal of the U.S., 29(5). Doran, P.T., R.A. Wharton, Jr., S.A. Spaulding, and J.S. Foster. 1994. Powers, L.E., D.W. Freckman, M. Ho, and R.A. Virginia. 1994. McMurdo McMurdo LTER: Paleolimnology of Taylor Valley, Antarctica. LTER: Soil and nematode distribution along an elevational gradient Antarctic Journal of the U.S., 29(5). in Taylor Valley, Antarctica. Anta rctic Journal of the U.S., 29(5). Fountain, A.G., B.H. Vaughn, and G.L. Dana. 1994. McMurdo LTER: Priscu, J.C. 1994. McMurdo LTER: Phytoplankton nutrient deficiency Glacial mass balances of Taylor Valley, Antarctica. Antarctic Jour- in lakes of the Taylor Valley, Antarctica. Antarctic Journal of the nab! the U.S., 29(5). U.S., 29(5). Hastings, J.T., and A.Z. Butt. 1994. McMurdo LTER: Developing a geo- Welch, K., W.B. Lyons, J.C. Priscu, R. Edwards, D.M. McKnight, H. graphic information system access system. Antarctic Journal of the House, and R.A. Wharton, Jr. 1994. McMurdo LTER: Inorganic U.S., 29(5). geochemical studies with special reference to calcium carbonate McKnight, D., H. House, and P. von Guerard. 1994. McMurdo LTER: dynamics. Antarctic Journal of the U.S., 29(5). -

Geology of Hut Point Peninsula, Ross Island

significantly below their Curie temperatures (approxi- Wilson, R. L., and N. D. Watkins. 1967. Correlation of mately 550°C.). petrology and natural magnetic polarity in Columbia Plateau basalts. Geophysical Journal of the Royal Astro- Previous work (Pucher, 1969; Stacey and Banerjee, nomical Society, 12(4): 405-424. 1974) indicates that the CRM intensity acquired in a low field is significantly less than the TRM intensity. It thus would appear that if a CRM induced at temperatures considerably below the Curie tempera- Geology of Hut Point Peninsula, ture, contributes a significant proportion to the ob- Ross Island served NRM intensity, too low an intensity value will be assigned to the ancient field. Although it is too early to report a firm value for PHILIP R. KYLE the intensity of the ancient field during the imprint- Department of Geology ing of unit 13 and related flows, we think that the Victoria University strength of the ambient field was more likely to Wellington, New Zealand have been about 0.5 oe (based on samples at about 141 meters) than about 0.1 oe (based on samples SAMUEL B. TREVES 122.18 and 126.06 meters). The virtual dipole Department of Geology moment (Smith, 1967b) calculated for an estimated University of Nebraska field intensity of 0.5 oe at the site is 7 X 10 25 gauss Lincoln, Nebraska 68508 cubic centimeters. This is larger than the value of 5.5 X 1025 gauss cubic centimeters (Smith, 1967b) Hut Point Peninsula is about 20 kilometers long calculated on the basis of paleointensity experiments and 2 to 4 kilometers wide. -

Can Climate Warming Induce Glacier Advance in Taylor Valley, Antarctica?

556 Journal of Glaciology, Vol. 50, No. 171, 2004 Can climate warming induce glacier advance in Taylor Valley, Antarctica? Andrew G. FOUNTAIN,1 Thomas A. NEUMANN,2 Paul L. GLENN,1* Trevor CHINN3 1Departments of Geology and Geography, Portland State University, PO Box 751, Portland, Oregon 97207, USA E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Earth and Space Sciences, Box 351310, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195-1310, USA 3R/20 Muir RD. Lake Hawea RD 2, Wanaka, New Zealand ABSTRACT. Changes in the extent of the polar alpine glaciers within Taylor Valley, Antarctica, are important for understanding past climates and past changes in ice-dammed lakes. Comparison of ground-based photographs, taken over a 20 year period, shows glacier advances of 2–100 m. Over the past 103 years the climate has warmed. We hypothesize that an increase in average air temperature alone can explain the observed glacier advance through ice softening. We test this hypothesis by using a flowband model that includes a temperature-dependent softness term. Results show that, for a 28C warming, a small glacier (50 km2) advances 25 m and the ablation zone thins, consistent with observations. A doubling of snow accumulation would also explain the glacial advance, but predicts ablation-zone thickening, rather than thinning as observed. Problems encountered in modeling glacier flow lead to two intriguing but unresolved issues. First, the current form of the shape factor, which distributes the stress in simple flow models, may need to be revised for polar glaciers. Second, the measured mass-balance gradient in Taylor Valley may be anomalously low, compared to past times, and a larger gradient is required to develop the glacier profiles observed today. -

Draft ASMA Plan for Dry Valleys

Measure 18 (2015) Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Managed Area No. 2 MCMURDO DRY VALLEYS, SOUTHERN VICTORIA LAND Introduction The McMurdo Dry Valleys are the largest relatively ice-free region in Antarctica with approximately thirty percent of the ground surface largely free of snow and ice. The region encompasses a cold desert ecosystem, whose climate is not only cold and extremely arid (in the Wright Valley the mean annual temperature is –19.8°C and annual precipitation is less than 100 mm water equivalent), but also windy. The landscape of the Area contains mountain ranges, nunataks, glaciers, ice-free valleys, coastline, ice-covered lakes, ponds, meltwater streams, arid patterned soils and permafrost, sand dunes, and interconnected watershed systems. These watersheds have a regional influence on the McMurdo Sound marine ecosystem. The Area’s location, where large-scale seasonal shifts in the water phase occur, is of great importance to the study of climate change. Through shifts in the ice-water balance over time, resulting in contraction and expansion of hydrological features and the accumulations of trace gases in ancient snow, the McMurdo Dry Valley terrain also contains records of past climate change. The extreme climate of the region serves as an important analogue for the conditions of ancient Earth and contemporary Mars, where such climate may have dominated the evolution of landscape and biota. The Area was jointly proposed by the United States and New Zealand and adopted through Measure 1 (2004). This Management Plan aims to ensure the long-term protection of this unique environment, and to safeguard its values for the conduct of scientific research, education, and more general forms of appreciation. -

Xrf Analyses of Granitoids and Associated

X.R.F ANALYSES OF GRANITOIDS AND ASSOCIATED ROCKS FROM SOUTH VICTORIA LAND, ANTARCTICA K. Palmer Analytical Facility Victoria University of Wellington Private Bag Wellington NEW ZEALAND Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 Sample Preparation 2 Analytical Procedures 4 Acknowledgments 5 References 6 Tables of Analytical Data 11 Tables of Sample Descriptions 17 Location Maps 22 Appendix 1 23 Appendix 2 Research School of Earth Sciences Geology Board of Studies Publication No.3 Victoria University of Wellington ISSN 0113-1168 Analytical Facility Contribution No. 12 ISSN 0111-1337 Antarctic Data Series No.13 ISSN 0375-8192 1987 INTRODUCTION The granitoid rocks of South Victoria Land are represented in some of the earliest geological studies of Antarctica. Indeed as early as 1841 granitoids were dredged from the sea-floor off Victoria Land on the voyages of the Erebus and Terror. Early workers such as Ferrar and Prior described granitoids collected in situ by members of the Discovery expedition (1901-1904). Some years later further granitoid descriptions and the occasional chemical analysis were presented by such workers as David, Priestly, Mawson and Smith. In more recent times, samples collected by Gunn and Warren (1962) and analysed by the United States Geological Survey were presented in Harrington et.al. (1967). The first detailed study of granitoids in South Victoria Land was by Ghent & Henderson (1968) who, although examining only a small area in the lower Taylor Valley revealed for the first time the diverse range of granitoid types and emplacement processes in this region. This work was followed up by a relatively detailed major and trace element geochemical study, (Ghent,1970). -

Living and Working at USAP Facilities

Chapter 6: Living and Working at USAP Facilities CHAPTER 6: Living and Working at USAP Facilities McMurdo Station is the largest station in Antarctica and the southermost point to which a ship can sail. This photo faces south, with sea ice in front of the station, Observation Hill to the left (with White Island behind it), Minna Bluff and Black Island in the distance to the right, and the McMurdo Ice Shelf in between. Photo by Elaine Hood. USAP participants are required to put safety and environmental protection first while living and working in Antarctica. Extra individual responsibility for personal behavior is also expected. This chapter contains general information that applies to all Antarctic locations, as well as information specific to each station and research vessel. WORK REQUIREMENT At Antarctic stations and field camps, the work week is 54 hours (nine hours per day, Monday through Saturday). Aboard the research vessels, the work week is 84 hours (12 hours per day, Monday through Sunday). At times, everyone may be expected to work more hours, assist others in the performance of their duties, and/or assume community-related job responsibilities, such as washing dishes or cleaning the bathrooms. Due to the challenges of working in Antarctica, no guarantee can be made regarding the duties, location, or duration of work. The objective is to support science, maintain the station, and ensure the well-being of all station personnel. SAFETY The USAP is committed to safe work practices and safe work environments. There is no operation, activity, or research worth the loss of life or limb, no matter how important the future discovery may be, and all proactive safety measures shall be taken to ensure the protection of participants. -

The Antarctic Sun, December 19, 1999

On the Web at http://www.asa.org December 19, 1999 Published during the austral summer at McMurdo Station, Antarctica, for the United States Antarctic Program Ski-plane crashes at AGO-6 By Aaron Spitzer The Antarctic Sun Two pilots escaped injury Sunday when their Twin Otter aircraft crashed during takeoff from an isolated landing site in East Antarctica. The plane, a deHavilland Twin Otter turboprop owned by Kenn Borek Air Ltd. and chartered to the U.S. Antarc- tic Program, was taking off around 3:15 p.m. Sunday when it caught a ski in the snow and tipped sideways. A wing hit the ground and the plane suffered Congratulations, it’s a helicopter! extensive damage. A New Zealand C-130 delivers a Bell 212 helicopter to the ice runway last week. The new The accident occurred on a tempo- arrival took the place of the Royal New Zealand Air Force helo used in the first part of the rary skiway at Automated Geophysical season. Photo by Ed Bowen. Observatory 6, located in Wilkes Land, about 800 miles northwest of McMurdo. The pilots had flown to the site earlier in the day from McMurdo Station to drop Testing tainted waters off two runway groomers, who were preparing the strip for the arrival of an By Josh Landis LC-130 Hercules ski-plane. The Antarctic Sun On Monday afternoon, another Kenn Borek Twin Otter, chartered to the Most scientists come to Antarctica because it gives them a chance to do their Italian Antarctic Program at Terra Nova work in the most pristine conditions on Earth. -

Flnitflrcililcl

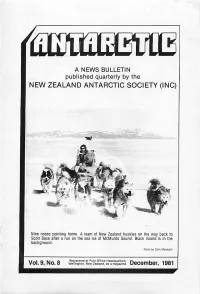

flNiTflRCililCl A NEWS BULLETIN published quarterly by the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY (INC) svs-r^s* ■jffim Nine noses pointing home. A team of New Zealand huskies on the way back to Scott Base after a run on the sea ice of McMurdo Sound. Black Island is in the background. Pholo by Colin Monteath \f**lVOL Oy, KUNO. O OHegisierea Wellington, atNew kosi Zealand, uttice asHeadquarters, a magazine. n-.._.u—December, -*r\n*1981 SOUTH GEORGIA SOUTH SANDWICH Is- / SOUTH ORKNEY Is £ \ ^c-c--- /o Orcadas arg \ XJ FALKLAND Is /«Signy I.uk > SOUTH AMERICA / /A #Borga ) S y o w a j a p a n \ £\ ^> Molodezhnaya 4 S O U T H Q . f t / ' W E D D E L L \ f * * / ts\ xr\ussR & SHETLAND>.Ra / / lj/ n,. a nn\J c y DDRONNING d y ^ j MAUD LAND E N D E R B Y \ ) y ^ / Is J C^x. ' S/ E A /CCA« « • * C",.,/? O AT S LrriATCN d I / LAND TV^ ANTARCTIC \V DrushsnRY,a«feneral Be|!rano ARG y\\ Mawson MAC ROBERTSON LAND\ \ aust /PENINSULA'5^ *^Rcjnne J <S\ (see map below) VliAr^PSobral arg \ ^ \ V D a v i s a u s t . 3_ Siple _ South Pole • | U SA l V M I IAmundsen-Scott I U I I U i L ' l I QUEEN MARY LAND ^Mir"Y {ViELLSWORTHTTH \ -^ USA / j ,pt USSR. ND \ *, \ Vfrs'L LAND *; / °VoStOk USSR./ ft' /"^/ A\ /■■"j■ - D:':-V ^%. J ^ , MARIE BYRD\Jx^:/ce She/f-V^ WILKES LAND ,-TERRE , LAND \y ADELIE ,'J GEORGE VLrJ --Dumont d'Urville france Leningradskaya USSR ,- 'BALLENY Is ANTARCTIC PENIMSULA 1 Teniente Matienzo arg 2 Esperanza arg 3 Almirante Brown arg 4 Petrel arg 5 Deception arg 6 Vicecomodoro Marambio arg ' ANTARCTICA 7 Arturo Prat chile 8 Bernardo O'Higgins chile 9 P r e s i d e n t e F r e i c h i l e : O 5 0 0 1 0 0 0 K i l o m e t r e s 10 Stonington I. -

Soil Toxicity in Antarctic Dry Valleys

of 1967-1968 have been examined at the Jet Propul sion Laboratory to determine their toxicity. During a traverse made with Prof. Robert E. Benoit of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute, 18 soil samples were collected at depths up to four inches near the head of the Matterhorn Glacier in the Asgard Range (Fig. 2), on a ridge east of Rhone Glacier at 1,867 m, and in an intersecting east-west valley that extends from the Matterhorn to Lake Bonney in Taylor Valley at an elevation of 107 m. Two additional samples, nos. 632 and 639, were obtained on the northern side of the Asgard Range, above Wright Valley. Soil Toxicity in Antarctic Dry Valleys1 ROY E. CAMERON, CHARLES N. DAVID, Figure 1, Location of antarctic soil-sample sites. and JONATHAN KING The soils were collected aseptically by techniques Bioscience Section developed for sampling and handling desert soils Jet Propulsion Laboratory (Cameron et al, 1966). Microbiological analyses California Institute of Technology were performed by methods previously reported for samples from this region (Boyd et al., 1966; Soils collected in various dry valleys (Fig. 1) of Cameron, 1967). southern Victoria Land during the antarctic summer Soil Toxicity Test 1This paper presents the results of one phase of research carried out at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California All samples were kept frozen until analyzed. Micro Institute of Technology, under contract no. NAS 7-100, biological analyses were performed on the 18 samples sponsored by the National Aeronautics and Space Adminis tration. Logistic support and facilities for the portion of while they contained the in situ moisture.