Eddie Stout, Dialtone Records, and the Making of a Blues Scene in Austin1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neil Foster Carries on Hating Keith Listens To

April 2017 April 96 In association with "AMERICAN MUSIC MAGAZINE" ALL ARTICLES/IMAGES ARE COPYRIGHT OF THEIR RESPECTIVE AUTHORS. FOR REPRODUCTION, PLEASE CONTACT ALAN LLOYD VIA TFTW.ORG.UK Chuck Berry, Capital Radio Jazzfest, Alexandra Palace, London, 21-07-79, © Paul Harris Neil Foster carries on hating Keith listens to John Broven The Frogman's Surprise Birthday Party We “borrow” more stuff from Nick Cobban Soul Kitchen, Jazz Junction, Blues Rambling And more.... 1 2 An unidentified man spotted by Bill Haynes stuffing a pie into his face outside Wilton’s Music Hall mumbles: “ HOLD THE THIRD PAGE! ” Hi Gang, Trust you are all well and as fluffy as little bunnies for our spring edition of Tales From The Woods Magazine. WOW, what a night!! I'm talking about Sunday 19th March at Soho's Spice Of Life venue. Charlie Gracie and the TFTW Band put on a show to remember, Yes, another triumph for us, just take a look at the photo of Charlie on stage at the Spice, you can see he was having a ball, enjoying the appreciation of the audience as much as they were enjoying him. You can read a review elsewhere within these pages, so I won’t labour the point here, except to offer gratitude to Charlie and the Tales From The Woods Band for making the evening so special, in no small part made possible by David the excellent sound engineer whom we request by name for our shows. As many of you have experienced at Rock’n’Roll shows, many a potentially brilliant set has been ruined by poor © Paul Harris sound, or literally having little idea how to sound up a vintage Rock’n’Roll gig. -

Jerry Williams Jr. Discography

SWAMP DOGG - JERRY WILLIAMS, JR. DISCOGRAPHY Updated 2016.January.5 Compiled, researched and annotated by David E. Chance: [email protected] Special thanks to: Swamp Dogg, Ray Ellis, Tom DeJong, Steve Bardsley, Pete Morgan, Stuart Heap, Harry Grundy, Clive Richardson, Andy Schwartz, my loving wife Asma and my little boy Jonah. News, Info, Interviews & Articles Audio & Video Discography Singles & EPs Albums (CDs & LPs) Various Artists Compilations Production & Arrangement Covers & Samples Miscellaneous Movies & Television Song Credits Lyrics ================================= NEWS, INFO, INTERVIEWS & ARTICLES: ================================= The Swamp Dogg Times: http://www.swampdogg.net/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/SwampDogg Twitter: https://twitter.com/TheSwampDogg Swamp Dogg's Record Store: http://swampdogg.bandcamp.com/ http://store.fastcommerce.com/render.cz?method=index&store=sdeg&refresh=true LIVING BLUES INTERVIEW The April 2014 issue of Living Blues (issue #230, vol. 45 #2) has a lengthy interview and front cover article on Swamp Dogg by Gene Tomko. "There's a Lot of Freedom in My Albums", front cover + pages 10-19. The article includes a few never-before-seen vintage photos, including Jerry at age 2 and a picture of him talking with Bobby "Blue" Bland. The issue can be purchased from the Living Blues website, which also includes a nod to this online discography you're now viewing: http://www.livingblues.com/ SWAMP DOGG WRITES A BOOK PROLOGUE Swamp Dogg has written the prologue to a new book, Espiritus en la Oscuridad: Viaje a la era soul, written by Andreu Cunill Clares and soon to be published in Spain by 66 rpm Edicions: http://66-rpm.com/ The jacket's front cover is a photo of Swamp Dogg in the studio with Tommy Hunt circa 1968. -

&Blues GUITAR SHORTY

september/october 2006 issue 286 free jazz now in our 32nd year &blues report www.jazz-blues.com GUITAR SHORTY INTERVIEWED PLAYING HOUSE OF BLUES ARMED WITH NEW ALLIGATOR CD INSIDE: 2006 Gift Guide: Pt.1 GUITAR SHORTY INTERVIEWED Published by Martin Wahl By Dave Sunde Communications geles on a rare off day from the road. Editor & Founder Bill Wahl “I would come home from school and sneak in to my uncle Willie’s bedroom Layout & Design Bill Wahl and try my best to imitate him playing the guitar. I couldn’t hardly get my Operations Jim Martin arms over the guitar, so I would fall Pilar Martin down on the floor and throw tantrums Contributors because I couldn’t do what I wanted. Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Grandma finally had enough of all that Dewey Forward, Steve Homick, and one morning she told my Uncle Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Willie point blank, I want you to teach Peanuts, Mark Smith, Dave this boy how to ‘really’ play the guitar Sunde, Duane Verh and Ron before I kill him,” said Shorty Weinstock. Photos of Guitar Shorty Fast forward through years of late courtesy of Alligator Records night static filled AM broadcasts crackling the southbound airwaves out of Cincinnati that helped further de- Check out our costantly updated website. Now you can search for CD velop David’s appreciative musical ear. Reviews by artists, Titles, Record T. Bone Walker, B.B. King and Gospel Labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 innovator Sister Rosetta Tharpe were years of reviews are up and we’ll be the late night companions who spent going all the way back to 1974. -

Guide to the Martin Williams Collection

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago CBMR Collection Guides / Finding Aids Center for Black Music Research 2020 Guide to the Martin Williams Collection Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cmbr_guides Part of the History Commons, and the Music Commons Columbia COLLEGE CHICAGO CENTER FOR BLACK MUSIC RESEARCH COLLECTION The Martin Williams Collection,1945-1992 EXTENT 7 boxes, 3 linear feet COLLECTION SUMMARY Mark Williams was a critic specializing in jazz and American popular culture and the collection includes published articles, unpublished manuscripts, files and correspondence, and music scores of jazz compositions. PROCESSING INFORMATION The collection was processed, and a finding aid created, in 2010. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Martin Williams [1924-1992] was born in Richmond Virginia and educated at the University of Virginia (BA 1948), the University of Pennsylvania (MA 1950) and Columbia University. He was a nationally known critic, specializing in jazz and American popular culture. He wrote for major jazz periodicals, especially Down Beat, co-founded The Jazz Review and was the author of numerous books on jazz. His book The Jazz Tradition won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in music criticism in 1973. From 1971-1981 he directed the Jazz and American Culture Programs at the Smithsonian Institution, where he compiled two widely respected collections of recordings, The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz, and The Smithsonian Collection of Big Band Jazz. His liner notes for the latter won a Grammy Award. SCOPE & CONTENT/COLLECTION DESCRIPTION Martin Williams preferred to retain his writings in their published form: there are many clipped articles but few manuscript drafts of published materials in his files. -

On the Road to Memphis

Ottawa BLUES Society Winter 2008 MonkeyJunk In this issue: OBS AGM & Christmas Party 3 Save DAWG FM 4 Kat Danser’s Blues Pilgrimage 6 On the Road to Cisco Bluesfest News 8 Blues on the Rideau 10 International Blues Challenge 12 Memphis CD Reviews 13 Postcards From The Road 18 Corporate Directory 22 New and Renewing OBS Members – July-December 2008 We welcome two new Corporate Members to the Ottawa Blues Society Gerald Baillie, David Bedard, Pierre Brisson, Ross Brown & Lori Kerfoot, Colin Chesterman, Brian Clark, Bob Crane (family), Louise Dontigny, James Doran & Diane Leduc-Doran, Jean-Louis Dubé, Alison Edgar, Cleo Evans, Bernard Fournier, Robewrt Gowan, Mike Graham, Sandy Kusugak, Jeff Lockhart, Jack Logan, Annette Longchamps, Hugh MacEachern, Fraser Manson, Tom Morelli, Tom Morris, Gary and Vickie Paradis, Roxanne Pilon, Terry Perkins, Chris Pudney, Jeff Roberts, Mark Roberts, Tom Rowe, Jim Roy (benefactor), Bill Saunders, Ursula Scherfer, Ken Stasiak, John Swayze, Liz Sykes (benefactor), Ian Tomlinson, Chris & Linda Waite, Gord White, Larry Williams, Ross Wilson, Linda and Pat Yarema www.worksburger.com www.lorenzos.ca 2 OBScene Deadlines 3 OBS CONTACTS OBS Annual General Meeting Issue Copy Deadline Distribution Date Website: www.OttawaBluesSociety.com OBS Mission Spring March 15 Online in April & Christmas Party E-mail: Please use feedback form on website Summer June 15 Mailed in early July Saturday, December 6, 2008 CORRESPONDENCE AND ADDRESS CHANGES To foster appreciation, Ottawa Blues Society promotion, preservation P.O. Box 708, Station “B” The OBS AGM got underway at 8:15 pm with Cover charges for this event, along with money From the Editor … and enjoyment of the Ottawa, ON K1P 5P8 reports from the President and Board Members. -

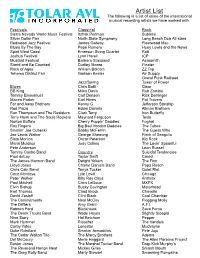

Artist List the Following Is a List of Some of the International Musical Recording Artists We Have Worked With

Artist List The following is a list of some of the international musical recording artists we have worked with. Festivals Classical Rock Sierra Nevada World Music Festival Itzhak Perlman Sublime Silver Dollar Fair North State Symphony Long Beach Dub All-stars Redwood Jazz Festival James Galway Fleetwood Mac Blues By The Bay Pepe Romero Huey Lewis and the News Spirit West Coast Emerson String Quartet Ratt Joshua Festival Lynn Harell ICP Mustard Festival Barbara Streisand Aerosmith Stand and Be Counted Dudley Moore Floater Rock of Ages William Bolcom ZZ Top Tehema District Fair Garison Keeler Air Supply Grand Funk Railroad Jazz/Swing Tower of Power Blues Chris Botti Gwar BB King Miles Davis Rob Zombie Tommy Emmanuel Carl Denson Rick Derringer Maceo Parker Earl Hines Pat Travers Far and Away Brothers Kenny G Jefferson Starship Rod Piaza Eddie Daniels Allman Brothers Ron Thompson and The Resistors Clark Terry Iron Butterfly Terry Hank and The Souls Rockers Maynard Ferguson Tesla Norton Buffalo Cherry Poppin’ Daddies Foghat Roy Rogers Big Bad Voodoo Daddies The Tubes Smokin’ Joe Cubecki Bobby McFerrin The Guess Who Joe Lewis Walker George Shearing Flock of Seagulls Sista Monica Oscar Peterson Kid Rock Maria Muldaur Judy Collins The Lovin’ Spoonful Pete Anderson Leon Russel Tommy Castro Band Country Suicidal Tendencies Paul deLay Taylor Swift Creed The James Harmon Band Dwight Yokem The Fixx Lloyd Jones Charlie Daniels Band Papa Roach Chris Cain Band Tanya Tucker Quiet Riot Coco Montoya Lyle Lovitt Chicago Peter Welker Billy Ray Cirus Anthrax Paul Mitchell Chris LeDoux MXPX Elvin Bishop Bucky Covington Motorhead Earl Thomas Chad Brock Chavelle David Zasloff Clint Black Coal Chamber The Commitments Neal McCoy Flogging Molly The Drifters Amy Grant A.F.I. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1638 HON

E1638 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks August 7, 1998 After a successful tenure as Commander of also served as a member of the Indiana Fiscal In honoring the memory of Gibby I feel there the 88th in Minnesota, he moved on to the Policy Institute and he was a council member are a few things that I must call attention to, Pentagon. He was assigned to the Assistant for the Boy Scouts of America. a few memories that, as I am sure, everyone Deputy Chief of Staff Operations, Mobilization Wally Miller is survived by his wife, June; who knew Gibby will agree with me on, must and Reserve Affairs. In addition, General children Beth Ingram, Aimee Riemke, Tom, be mentioned. One of these was Gibby's fas- Rehkamp was named to the Reserve Forces Michael Miller, stepsons Ben, Andy Camp; cination with sports. Gibby was truly a sports Policy Board (RFPB). The RFPB is rep- mother Connie Conklin Miller; sisters Beverly fanatic. He seemed to enjoy it most, though, resented by members of all of the uniformed Stevens, Barbara Miller, brothers V. Richard, when he could share his excitement and en- services. Members of the RFPB are respon- R. James Miller; and five grandchildren. thusiasm with others. He was very successful sible for policy advising to the Secretary of In closing, I can only begin to enumerate on in spreading his love of sports in many dif- Defense on matters relating to the reserve Wally Miller's long and distinguished list of ferent ways, whether it be by working for an components. -

Rebellion in LA

Kroger Update-5 #71 JULY/AUGUST 1992 FREE Midwifery-6 U.SPOST/ Rio Report-7 PAI AMN ARE, PERMIT NO Blues & Jazz-10 Community Events-11 ANN ARBOR'S ALTERNATIVE NEWSMONTHLY FORUM: RACISM IN AMERICA By Rachel Lanzerotti s legal abortions become harder and harder to obtain, there is a movement emerging to ensure that women will never have to return to the dark ages of the pre-Roe v. Wade era. AIn the wake of the S upreme Court's June 29 ruling, and a host of previous judicial setbacks, assistance networks like the Overground Railroad are being activated to guarantee a woman's access to an abortion. For a woman with an unwanted pregnancy, "access" means knowing PHOTO: TED SYLVESTER that abortion is an option; locating a practitioner who can provide a safe Ann Arbor responds to King verdict with downtown rally and march abortion; figuring out how to get to the practitioner; and finding the money for transportation and the procedure and maybe even food and lodging; and receiving information on how to care for herself following the abortion. As many abortion rights activists predicted, the Court's most recent ruling did not overturn Roe but continued to increase the number of Rebellion in LA. restrictions placed on a woman's access to abortion. Although the Court struck down Pennsylvania's requirement that a married woman notify her husband of apending abortion, it let stand the 24-hour "waiting period" for Michael Zinzun, a former mem- By Michael Zinzun out here. all women seeking abortions, and it let stand a parental notification ber of the Black Panther Party, has I called home yesterday and one requirement. -

Haam Annual Report 2013

PHOTO BY BRENDA LADD PHOTOGRAPHY HAAM ANNUAL REPORT 2013 www.myhaam.org Dear Friends of HAAM: The year 2013 brought many changes to the health care landscape in our nation, our community and to the Health Alliance for Austin Musicians (HAAM). But through it all, HAAM’s core values and mission remained rock solid. We love Austin. We love live music. And we love what HAAM does for Austin’s musicians. Two major changes affected HAAM in 2013. First, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) began to take effect—opening new doors for many HAAM members to obtain health insurance. Although some people thought that the ACA might reduce the need for HAAM, nothing could be further from the truth. Because Texas did not follow many other states and expand its Medicaid eligibility, more than 60% of current HAAM members still need HAAM to access affordable health care. Additionally, the ACA does not usually provide the dental, vision, hearing and other health care services that are currently available to HAAM members. The second major change for HAAM in 2013 was the departure of our much loved, longtime executive director, Carolyn Schwarz, who deftly guided the organization for eight years. We wish her well and welcome Reenie Collins to our team as executive director. A native Austinite with deep roots in the health care and non-profit community, Reenie is passionate about HAAM and its mission. Reenie has a long-standing history with the HAAM family and actually worked as a health care consultant to our founder Robin Shivers in 2005 when HAAM was being formed. -

Número 33 – Febrero 2014 * CULTURA BLUES. LA REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA

1 Número 33 – Febrero 2014 * CULTURA BLUES. LA REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA Índice Directorio PORTADA Blues Shock: Billy Branch & The Son Of Blues. Imagen cortesía de Blind Pig Records. Agradecimientos para el diseñador del arte: Eduardo Barrera Arambarri y al autor de la foto: Cultura Blues. La revista electrónica Tony Manguillo (1) ..………………………………………………………………….…………….. 1 “Un concepto distinto del blues y algo más…” www.culturablues.com ÍNDICE - DIRECTORIO ……..…………………………………………..….… 2 Esta revista es producida gracias al Programa EDITORIAL To blues or not to blues (2) ..…..………………….………… 3 “Edmundo Valadés” de Apoyo a la Edición de HUELLA AZUL Billy Branch. Entrevista exclusiva (3 y 4) .….….…. 4 Revistas Independientes 2013 del Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes DE COLECCIÓN Un disco, un video y un libro (5) ………………...... 7 EL ESCAPE DEL CONVICTO 20 grandes slides del blues eléctrico. Primera Parte (6) ................. 11 Año 4 Núm. 33 – febrero de 2014 Derechos Reservados 04 – 2013 – 042911362800 – 203 BLUES A LA CARTA Registro ante INDAUTOR Clapton está de vuelta, retrospectiva en doce capítulos. Capítulo once (5) ……………………………………………….………………………... 16 Director general y editor: José Luis García Fernández PERSONAJES DEL BLUES XI Nominados a los premios de la Blues Foundation (5) ………….......…..21 Subdirector general: José Alfredo Reyes Palacios LÍNEA A-DORADA Llegará la Paz (7) ....................................... 26 Diseñador: José Luis García Vázquez COLABORACIÓN ESPECIAL I Tres festivales de Blues en el centro del país Pt. III (8)…………...…..….29 Consejo Editorial: CULTURA BLUES EN… Luis Eduardo Alcántara Cruz Hospital de Pediatría. CMN Siglo XXI. Un camino acústico por Mario Martínez Valdez el blues. - Multiforo Cultural Alicia. Presentación del libro de María Luisa Méndez Flores Juan Pablo Proal: “Voy a morir. -

Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas

Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas BY Joshua Long 2008 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Geography __________________________________ Dr. Garth Andrew Myers, Chairperson __________________________________ Dr. Jane Gibson __________________________________ Dr. Brent Metz __________________________________ Dr. J. Christopher Brown __________________________________ Dr. Shannon O’Lear Date Defended: June 5, 2008. The Dissertation Committee for Joshua Long certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas ___________________________________ Dr. Garth Andrew Myers, Chairperson Date Approved: June 10, 2008 ii Acknowledgments This page does not begin to represent the number of people who helped with this dissertation, but there are a few who must be recognized for their contributions. Red, this dissertation might have never materialized if you hadn’t answered a random email from a KU graduate student. Thank you for all your help and continuing advice. Eddie, you revealed pieces of Austin that I had only read about in books. Thank you. Betty, thank you for providing such a fair-minded perspective on city planning in Austin. It is easy to see why so many Austinites respect you. Richard, thank you for answering all my emails. Seriously, when do you sleep? Ricky, thanks for providing a great place to crash and for being a great guide. Mycha, thanks for all the insider info and for introducing me to RARE and Mean-Eyed Chris. -

To Read/Download

1 President’s Column groups to attend our shows (with their membership cards) at SBS By Brandon Bentz, President member prices. My view is that we are one big community of Blues As we approach the New Year, it is time to lovers, and we need to be open-armed to each other. I also targeted sponsored shows at higher visibility venues, such as the Harmonica reflect on the past year. It is a useful exercise to undertake each year to critically evaluate Slapdown at the Harris Center. The Harris Center sends out their where you have been and where you want to seasonal mailers to 100,000+ members, and the advertising power go.I think this has been a great year, and could not be denied. In addition, their membership is a very affluent, I'd like to share with you how I became your educated, and involved group. We signed up 35 new individual and President. family memberships at that show. Our next show to be held there will be the Summer Soulstice 2019 with Wee Willie Walker, Terri I took over the Presidency a little less than a year ago, when Renee Odabi, and the Anthony Paule Soul Orchestra. Hope to see you Erickson was suddenly faced with a serious health problem. I had there. taken the Vice Presidency over just a few months earlier when the former VP stepped down. The Board voted me into the VP spot, to Next was the Board membership crisis. If we fell below a critical fill the vacancy and introduce new blood and new ideas.