Crime, Communities and Authority In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Wales PREPARING for EMERGENCIES Contents

North Wales PREPARING FOR EMERGENCIES Contents introduction 4 flooding 6 severe weather 8 pandemic 10 terrorist incidents 12 industrial incidents 14 loss of critical infrastructure 16 animal disease 18 pollution 20 transport incidents 22 being prepared in the home 24 businesses being prepared 26 want to know more? 28 Published: Autumn 2020 introduction As part of the work of agencies involved in responding the counties of Cheshire and data), which is largely preparing for emergencies to emergencies – the Shropshire) and to the South by concentrated in the more across the region, key emergency services, local the border with mid-Wales industrial and urbanised areas partners work together to authorities, health, environment (specifically the counties of of the North East and along prepare the North Wales and utility organisations. Powys and Ceredigion). the North Wales coast. The Community Risk Register. population increases significantly The overall purpose is to ensure The land area of North Wales is during summer months. Less This document provides representatives work together to approximately 6,172 square than a quarter (22.32%) of the information on the biggest achieve an appropriate level of kilometres (which equates to total Welsh population lives in emergencies that could happen preparedness to respond to 29% of the total land area of North Wales. in the region and includes the emergencies that may have a Wales), and the coastline is impact on people, communities, significant impact on the almost 400 kilometres long. Over the following pages, we the environment and local communities of North Wales. will look at the key risks we face North Wales is divided into six businesses. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

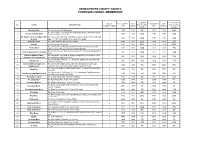

Proposed Arrangements Table

DENBIGHSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL PROPOSED COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP % variance % variance No. OF ELECTORATE 2017 ELECTORATE 2022 No. NAME DESCRIPTION from County from County COUNCILLORS 2017 RATIO 2022 RATIO average average 1 Bodelwyddan The Community of Bodelwyddan 1 1,635 1,635 3% 1,828 1,828 11% The Communities of Cynwyd 468 (494) and Llandrillo 497 (530) and the 2 Corwen and Llandrillo 2 2,837 1,419 -11% 2,946 1,473 -11% Town of Corwen 1,872 (1,922) Denbigh Central and Upper with The Community of Henllan 689 (752) and the Central 1,610 (1,610) and 3 3 4,017 1,339 -16% 4,157 1,386 -16% Henllan Upper 1,718 (1,795) Wards of the Town of Denbigh 4 Denbigh Lower The Lower Ward of the Town of Denbigh 2 3,606 1,803 13% 3,830 1,915 16% 5 Dyserth The Community of Dyserth 1 1,957 1,957 23% 2,149 2,149 30% The Communities of Betws Gwerfil Goch 283 (283), Clocaenog 196 6 Efenechtyd 1 1,369 1,369 -14% 1,528 1,528 -7% (196), Derwen 375 (412) and Efenechtyd 515 (637). The Communities of Llanarmonmon-yn-Ial 900 (960) and Llandegla 512 7 Llanarmon-yn-Iâl and Llandegla 1 1,412 1,412 -11% 1,472 1,472 -11% (512) Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd, The Communities of Llanbedr Dyffryn Clwyd 669 (727), Llanferres 658 8 1 1,871 1,871 18% 1,969 1,969 19% Llanferres and Llangynhafal (677) and Llangynhafal 544 (565) The Community of Aberwheeler 269 (269), Llandyrnog 869 (944) and 9 Llandyrnog 1 1,761 1,761 11% 1,836 1,836 11% Llanynys 623 (623) Llanfair Dyffryn Clwyd and The Community of Bryneglwys 307 (333), Gwyddelwern 403 (432), 10 1 1,840 1,840 16% 2,056 2,056 25% Gwyddelwern Llanelidan -

The Cefn Cefn Mawr.Pdf

FORWARD All the recommendations made in this document for inclusion in the WCBC LDP2 are for the betterment of our community of The Cefn and Cefn Mawr at the Central section of the Pontcysyllte World Heritage Site. The picture opposite is an impression of what the Plas Kynaston Canal and Marina would look like with Open Park Land on one side and an appropriate housing development on the other. This would turn the former brown field Monsanto site in Cefn Mawr around for everyone in the county of Wrexham. By the PKC Group LDP2 - THE CEFN & CEFN MAWR LDP2 - THE CEFN & CEFN MAWR Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Public Support ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Communication ...................................................................................................................................... 6 LDP2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 7 LDP2 Objectives & PKC Group Responses ............................................................................................. 7 The Cefn & Cefn Mawr and Wrexham County .................................................................................... 10 Key Issues and Drivers for the LDP2 & Responses ............................................................................. -

Chapman, 2013) Anglesey Bridge of Boats Documentary and Historical (Menai and Anglesey) Research (Chapman, 2013)

MEYSYDD BRWYDRO HANESYDDOL HISTORIC BATTLEFIELDS IN WALES YNG NGHYMRU The following report, commissioned by Mae’r adroddiad canlynol, a gomisiynwyd the Welsh Battlefields Steering Group and gan Grŵp Llywio Meysydd Brwydro Cymru funded by Welsh Government, forms part ac a ariennir gan Lywodraeth Cymru, yn of a phased programme of investigation ffurfio rhan o raglen archwilio fesul cam i undertaken to inform the consideration of daflu goleuni ar yr ystyriaeth o Gofrestr a Register or Inventory of Historic neu Restr o Feysydd Brwydro Hanesyddol Battlefields in Wales. Work on this began yng Nghymru. Dechreuwyd gweithio ar in December 2007 under the direction of hyn ym mis Rhagfyr 2007 dan the Welsh Government’sHistoric gyfarwyddyd Cadw, gwasanaeth Environment Service (Cadw), and followed amgylchedd hanesyddol Llywodraeth the completion of a Royal Commission on Cymru, ac yr oedd yn dilyn cwblhau the Ancient and Historical Monuments of prosiect gan Gomisiwn Brenhinol Wales (RCAHMW) project to determine Henebion Cymru (RCAHMW) i bennu pa which battlefields in Wales might be feysydd brwydro yng Nghymru a allai fod suitable for depiction on Ordnance Survey yn addas i’w nodi ar fapiau’r Arolwg mapping. The Battlefields Steering Group Ordnans. Sefydlwyd y Grŵp Llywio was established, drawing its membership Meysydd Brwydro, yn cynnwys aelodau o from Cadw, RCAHMW and National Cadw, Comisiwn Brenhinol Henebion Museum Wales, and between 2009 and Cymru ac Amgueddfa Genedlaethol 2014 research on 47 battles and sieges Cymru, a rhwng 2009 a 2014 comisiynwyd was commissioned. This principally ymchwil ar 47 o frwydrau a gwarchaeau. comprised documentary and historical Mae hyn yn bennaf yn cynnwys ymchwil research, and in 10 cases both non- ddogfennol a hanesyddol, ac mewn 10 invasive and invasive fieldwork. -

07501022017 Email: [email protected]

[email protected] @LlaisLlandyrnog The August Bank Holiday was very quiet this year, without the usual hustle and bustle around the village hall. The annual event is a great opportunity for the residents of Llandyrnog and its environs to get together purely to socialise, as well as to admire the wonderful produce and crafts exhibited. However, there has been an excellent response to an appeal for photographs in lieu of the show. This is a wonderful colourful version of the Llais, which is also available in print for the first time since March. Condolences: Bryn Bellis, Erw Frân, has Diamond Wedding Anniversary passed away following a long illness. We send Gwyn and Valerie were married at St Mary’s our sincerest sympathy to Carol and all the Church, Denbigh 27th August 1960, and the family. Our condolences also to Sylvia and reception was held at the Crown Hotel. They the family of the late Bill Evans, Fforddlas. have lived in Llandyrnog all their married We also send our regards to David and life. Gwyn ‘Dŵr’ retired from the Waterboard Margaret Jones, Hafan Dawel on the loss of many years ago and Valerie retired from the David’s sister, Eira Reece Jones. Infirmary. We would all like to wish you a very happy Get well soon: to Les Ward after his stay at anniversary and hope you have a wonderful Ysbyty Glan Clwyd. day. Love from all the family. The Kinmel Arms has reopened its doors since Wednesday 5th August. Obviously Golden wedding celebration: things feel a little different and there has Congratulations to Aeron and Menna Ellis, been hard work to put safety measures in Gader Goch, on celebrating their golden place along with a few ‘rules’. -

Key Stage 3 Early Modern Britain

KS3 Knowing History Early Modern Britain 1509–1760 Teacher Guide Key Stage 3 Early Modern Britain 1509–1760 Teacher Guide Robert Peal Text © Robert Peal 2016; Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Limited 2016 1 KS3 Knowing History Early Modern Britain 1509–1760 Teacher Guide William Collins’ dream of knowledge for all began with the publication of his first book in 1819. A self-educated mill worker, he not only enriched millions of lives, but also founded a flourishing publishing house. Today, staying true to this spirit, Collins books are packed with inspiration, innovation and practical expertise. They place you at the centre of a world of possibility and give you exactly what you need to explore it. Collins. Freedom to teach Published by Collins An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers The News Building 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF Text © Robert Peal 2016 Design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Robert Peal asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the Publisher. This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the Publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Llandyrnog up to the Year 1750

Clwyd Powys Archaeological Trust Historic Settlement Survey – Denbighshire - 2014 Landyrnog SJ 1070 6500 105968 Introduction Landyrnog is one of several historic settlements that developed along the eastern flank of the Vale of Clwyd, with the river itself little more than one kilometre to the west and the Clwydians rearing up 2km to the east. The surface of the land here is relatively flat but the church is positioned almost equidistantly from two converging streams and the ground falls away gently on the south side of the settlement. The B5429 runs through the settlement from north to south, and Denbigh lies to the west on the far side of the River Clwyd, about 5km away. This brief report examines the emergence and development of Llandyrnog up to the year 1750. For the more recent history of the settlement, it might be necessary to look at other sources of information and in particular at the origins and nature of the buildings within it. The accompanying map is offered only as an indicative guide to the historic settlement. The continuous line defining the historic core offers a visual interpretation of the area within which the settlement developed, based on our interpretation of the evidence currently to hand. It is not an immutable boundary line, and will require modification as new discoveries are made. The map does not show those areas or buildings that are statutorily designated, nor does it pick out those sites or features that are specifically mentioned in the text. We have not referenced the sources that have been examined to produce this report, but that information will be available in the Historic Environment Record (HER) maintained by the Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust. -

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook Discover the legends of the mighty princes of Gwynedd in the awe-inspiring landscape of North Wales PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK Front Cover: Criccieth Castle2 © Princes of Gwynedd 2013 of © Princes © Cadw, Welsh Government (Crown Copyright) This page: Dolwyddelan Castle © Conwy County Borough Council PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 3 Dolwyddelan Castle Inside this book Step into the dramatic, historic landscapes of Wales and discover the story of the princes of Gwynedd, Wales’ most successful medieval dynasty. These remarkable leaders were formidable warriors, shrewd politicians and generous patrons of literature and architecture. Their lives and times, spanning over 900 years, have shaped the country that we know today and left an enduring mark on the modern landscape. This guidebook will show you where to find striking castles, lost palaces and peaceful churches from the age of the princes. www.snowdoniaheritage.info/princes 4 THE PRINCES OF GWYNEDD TOUR © Sarah McCarthy © Sarah Castell y Bere The princes of Gwynedd, at a glance Here are some of our top recommendations: PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 5 Why not start your journey at the ruins of Deganwy Castle? It is poised on the twin rocky hilltops overlooking the mouth of the River Conwy, where the powerful 6th-century ruler of Gwynedd, Maelgwn ‘the Tall’, once held court. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If it’s a photo opportunity you’re after, then Criccieth Castle, a much contested fortress located high on a headland above Tremadog Bay, is a must. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If you prefer a remote, more contemplative landscape, make your way to Cymer Abbey, the Cistercian monastery where monks bred fine horses for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn ‘the Great’. -

Caerfallen, Ruthin LL15 1SN

Caerfallen, Ruthin LL15 1SN Researched and written by Zoë Henderson Edited by Gill. Jones & Ann Morgan 2017 HOUSE HISTORY RESEARCH Written in the language chosen by the volunteers and researchers & including information so far discovered PLEASE NOTE ALL THE HOUSES IN THIS PROJECT ARE PRIVATE AND THERE IS NO ADMISSION TO ANY OF THE PROPERTIES ©Discovering Old Welsh Houses Group [North West Wales Dendrochronolgy Project] Contents page no. 1. The Name 2 2. Dendrochronology 2 3. The Site and Building Description 3 4. Background History 6 5. 16th Century 10 5a. The Building of Caerfallen 11 6. 17th Century 13 7. 18th Century 17 8. 19th Century 18 9. 20th Century 23 10. 21st Century 25 Appendices 1. The Royal House of Cunedda 29 2. The De Grey family pedigree 30 3. The Turbridge family pedigree 32 4. Will of John Turbridge 1557 33 5. The Myddleton family pedigree 35 6. The Family of Robert Davies 36 7. Will of Evan Davies 1741 37 8. The West family pedigree 38 9. Will of John Garner 1854 39 1 Caerfallen, Ruthin, Denbighshire Grade: II* OS Grid Reference SJ 12755 59618 CADW no. 818 Date listed: 16 May 1978 1. The Name Cae’rfallen was also a township which appears to have had an Isaf and Uchaf area which ran towards Llanrydd from Caerfallen. Possible meanings of the name 'Caerfallen' 1. Caerfallen has a number of references to connections with local mills. The 1324 Cayvelyn could be a corruption of Caevelyn Field of the mill or Mill field. 2. Cae’rafallen could derive from Cae yr Afallen Field of the apple tree. -

The Lives of the Chief Justices of England

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com Cui.U.K. &3o 1 THE LIVES OK THE CHIEF JUSTICES ENGLAND. FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST TILL THE DEATH OF LORD TENTERDEN. By JOHN LOKD CAMPBELL, LL.D. F.E.S.E.: AUTHOR OF 'THE LIVES OF THE LOKD CHANCELLORS OF ENGLANd.' THIRD EDITION. IN FOUR VOLUMES.— Vol. II. LONDON: JOHN MUEKAY, ALBEMAELE STEEET. 1874. The right of Translation is reserved. Uniform with the present Work. LIVES OF THE LOED CHANCELLOBS, AND Keepers op the Great Skal op England, from the Earliest Times till the Reign of George the Fourth. By John Lord Campbell, LL.D. Fourth Edition. 10 vols. Crown 8vo. 6s. ' each. " A work of sterling merit — one of very great labour, of richly diversified interest, and, we arc satisfied, of lasting value and estimation. We doubt If there be half-a-dozen living men who could produce a Biographical Series on such a scale, at all likely to command so much applause from the candid among the iearned as well as from the curious of the laity." — Quarterly Review. &ONdON: PRINTEd BT WILLIAM CLOWES ANd SONS, STAMFORd STREET ANd CHARING CROSS. CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME. CHAPTER XI.— continued. LIVES OF THE CHIEF JUSTICES FROM THE DISMISSAL OF SIR EDWARD COKE TILL THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. Sir Nicholas Hyde, Page 1. His Reputation as a Lawyer, 1. His Con duct as Chief Justice of the King's Bench, 2. -

Historic Settlements in Denbighshire

CPAT Report No 1257 Historic settlements in Denbighshire THE CLWYD-POWYS ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST CPAT Report No 1257 Historic settlements in Denbighshire R J Silvester, C H R Martin and S E Watson March 2014 Report for Cadw The Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust 41 Broad Street, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 7RR tel (01938) 553670, fax (01938) 552179 www.cpat.org.uk © CPAT 2014 CPAT Report no. 1257 Historic Settlements in Denbighshire, 2014 An introduction............................................................................................................................ 2 A brief overview of Denbighshire’s historic settlements ............................................................ 6 Bettws Gwerfil Goch................................................................................................................... 8 Bodfari....................................................................................................................................... 11 Bryneglwys................................................................................................................................ 14 Carrog (Llansantffraid Glyn Dyfrdwy) .................................................................................... 16 Clocaenog.................................................................................................................................. 19 Corwen ...................................................................................................................................... 22 Cwm .........................................................................................................................................