James Farmer Interviewer: John F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Rights Movement and the Legacy of Martin Luther

RETURN TO PUBLICATIONS HOMEPAGE The Dream Is Alive, by Gary Puckrein Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: Excerpts from Statements and Speeches Two Centuries of Black Leadership: Biographical Sketches March toward Equality: Significant Moments in the Civil Rights Movement Return to African-American History page. Martin Luther King, Jr. This site is produced and maintained by the U.S. Department of State. Links to other Internet sites should not be construed as an endorsement of the views contained therein. THE DREAM IS ALIVE by Gary Puckrein ● The Dilemma of Slavery ● Emancipation and Segregation ● Origins of a Movement ● Equal Education ● Montgomery, Alabama ● Martin Luther King, Jr. ● The Politics of Nonviolent Protest ● From Birmingham to the March on Washington ● Legislating Civil Rights ● Carrying on the Dream The Dilemma of Slavery In 1776, the Founding Fathers of the United States laid out a compelling vision of a free and democratic society in which individual could claim inherent rights over another. When these men drafted the Declaration of Independence, they included a passage charging King George III with forcing the slave trade on the colonies. The original draft, attributed to Thomas Jefferson, condemned King George for violating the "most sacred rights of life and liberty of a distant people who never offended him." After bitter debate, this clause was taken out of the Declaration at the insistence of Southern states, where slavery was an institution, and some Northern states whose merchant ships carried slaves from Africa to the colonies of the New World. Thus, even before the United States became a nation, the conflict between the dreams of liberty and the realities of 18th-century values was joined. -

Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information

“The Top Ten” Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information (Asa) Philip Randolph • Director of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. • He was born on April 15, 1889 in Crescent City, Florida. He was 74 years old at the time of the March. • As a young boy, he would recite sermons, imitating his father who was a minister. He was the valedictorian, the student with the highest rank, who spoke at his high school graduation. • He grew up during a time of intense violence and injustice against African Americans. • As a young man, he organized workers so that they could be treated more fairly, receiving better wages and better working conditions. He believed that black and white working people should join together to fight for better jobs and pay. • With his friend, Chandler Owen, he created The Messenger, a magazine for the black community. The articles expressed strong opinions, such as African Americans should not go to war if they have to be segregated in the military. • Randolph was asked to organize black workers for the Pullman Company, a railway company. He became head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black labor union. Labor unions are organizations that fight for workers’ rights. Sleeping car porters were people who served food on trains, prepared beds, and attended train passengers. • He planned a large demonstration in 1941 that would bring 10,000 African Americans to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC to try to get better jobs and pay. The plan convinced President Roosevelt to take action. -

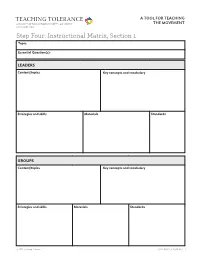

Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic: Essential Question(s): LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards GROUPS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: EVENTS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards HISTORICAL CONTEXT Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: OPPOSITION Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards TACTICS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: CONNECTIONS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 (SAMPLE) Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Martin Luther King Jr., A. -

Investigating the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Investigating the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Topic: Civil Rights History Grade level: Grades 4 – 6 Subject Area: Social Studies, ELA Time Required: 2 -3 class periods Goals/Rationale Bring history to life through reenacting a significant historical event. Raise awareness that the civil rights movement required the dedication of many leaders and organizations. Shed light on the power of words, both spoken and written, to inspire others and make progress toward social change. Essential Question How do leaders use written and spoken words to make change in their communities and government? Objectives Read, analyze and recite an excerpt from a speech delivered at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Identify leaders of the Civil Rights Movement; use primary source material to gather information. Reenact the March on Washington to gain a deeper understanding of this historic demonstration. Connections to Curriculum Standards Common Core State Standards CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.1 Quote accurately from a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text. CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.2 Determine two or more main ideas of a text and explain how they are supported by key details; summarize the text. CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.4 Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases in a text relevant to a grade 5 topic or subject area. CCSS.ELA-Literacy SL.5.6 Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and tasks, using formal English when appropriate to task and situation. National History Standards for Historical Thinking Standard 2: The student comprehends a variety of historical sources. -

Martin Luther King Jr January 2021

Connections Martin Luther King Jr January 2021 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PMB Administrative Services and the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Civil Rights Message from the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Administrative Services January 2021 Dear Colleagues, The life and legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., inspires me every day, particularly when the troubles of the world seem to have placed what appear to be insurmountable obstacles on the path to achieving Dr. King’s vision. Yet I know that those obstacles will eventually melt away when we focus our hearts and minds on finding solutions together. While serving as leaders of the civil rights movement, Dr. and Mrs. King raised their family in much the same way my dear parents raised my brothers and myself. It gives me comfort to know that at the end of the day, their family came together in love and faith the same way our family did, grateful for each other and grateful knowing the path ahead was illuminated by a shared dream of a fair and equitable world. This issue of Connections begins on the next page with wise words of introduction from our collaborative partner, Erica White-Dunston, Director of the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Civil Rights. Erica speaks eloquently of Dr. King’s championing of equity, diversity and inclusion in all aspects of life long before others understood how critically important those concepts were in creating and sustaining positive outcomes. I hope you find as much inspiration and hope within the pages of this month’s Connections magazine as I did. -

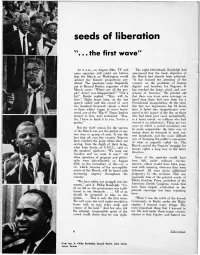

The First Wave

seeds of liberation " ... the first ",ave" At 9 a.m., on August 28th, TV and The night beforehand, Randolph had news reporters still could not believe announced that the basic objective of that the March on Washington would the March had already been achieved: achieve the historic proportions pre• "It has focused the attention of the dicted. The questions most frequently country on the problems of human put to Bayard Rustin, organizer of the dignity and freedom for Negroes. It March, were: "Where are all the peo• has reached the heart, mind, and con• ple ? Aren't you disappointed?" "Not a science of America." He pointed out' bit," Rustin replied. "They will be that there was more news coverage on here." Eight hours later, as the last hand than there had ever been for a speech ended and the crowd of over Presidential inauguration. At the time, two hundred thousand (about a third this fact was impressive, but 24 hours of them white) began to move home• later it faded into insignificance com• ward, one of the "Big 6" Negro leaders pared to the impact of the day on those turned to him and exclaimed: "Rus• who had taken part (and, undoubtedly, tin, I have to hand it to you. You're a to a lesser extent, on millions who had genius." viewed it on television). There are two ways in which a social revolution can But the chief reason for the success be made respectable: the false way of of the March was not the genius of any toning down its demands to meet cur• one man or group of men. -

Inspired by Gandhi and the Power of Nonviolence: African American

Inspired by Gandhi and the Power of Nonviolence: African American Gandhians Sue Bailey and Howard Thurman Howard Thurman (1899–1981) was a prominent theologian and civil rights leader who served as a spiritual mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr. Sue Bailey Thurman, (1903–1996) was an American author, lecturer, historian and civil rights activist. In 1934, Howard and Sue Thurman, were invited to join the Christian Pilgrimage of Friendship to India, where they met with Mahatma Gandhi. When Thurman asked Gandhi what message he should take back to the United States, Gandhi said he regretted not having made nonviolence more visible worldwide and famously remarked, "It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world." In 1944, Thurman left his tenured position at Howard to help the Fellowship of Reconciliation establish the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco. He initially served as co-pastor with a white minister, Dr. Alfred Fisk. Many of those in congregation were African Americans who had migrated to San Francisco for jobs in the defense industry. This was the first major interracial, interdenominational church in the United States. “It is to love people when they are your enemy, to forgive people when they seek to destroy your life… This gives Mahatma Gandhi a place along side all of the great redeemers of the human race. There is a striking similarity between him and Jesus….” Howard Thurman Source: Howard Thurman; Thurman Papers, Volume 3; “Eulogy for Mahatma Gandhi:” February 1, 1948; pp. 260 Benjamin Mays (1894–1984) -was a Baptist minister, civil rights leader, and a distinguished Atlanta educator, who served as president of Morehouse College from 1940 to 1967. -

Civil Rights Done Right a Tool for Teaching the Movement TEACHING TOLERANCE

Civil Rights Done Right A Tool for Teaching the Movement TEACHING TOLERANCE Table of Contents Introduction 2 STEP ONE Self Assessment 3 Lesson Inventory 4 Pre-Teaching Reflection 5 STEP TWO The "What" of Teaching the Movement 6 Essential Content Coverage 7 Essential Content Coverage Sample 8 Essential Content Areas 9 Essential Content Checklist 10 Essential Content Suggestions 12 STEP THREE The "How" of Teaching the Movement 14 Implementing the Five Essential Practices 15 Implementing the Five Essential Practices Sample 16 Essential Practices Checklist 17 STEP FOUR Planning for Teaching the Movement 18 Instructional Matrix, Section 1 19 Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Sample 23 Instructional Matrix, Section 2 27 Instructional Matrix, Section 2 Sample 30 STEP FIVE Teaching the Movement 33 Post-Teaching Reflection 34 Quick Reference Guide 35 © 2016 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT // 1 TEACHING TOLERANCE Civil Rights Done Right A Tool for Teaching the Movement Not long ago, Teaching Tolerance issued Teaching the Movement, a report evaluating how well social studies standards in all 50 states support teaching about the modern civil rights movement. Our report showed that few states emphasize the movement or provide classroom support for teaching this history effectively. We followed up these findings by releasingThe March Continues: Five Essential Practices for Teaching the Civil Rights Movement, a set of guiding principles for educators who want to improve upon the simplified King-and-Parks-centered narrative many state standards offer. Those essential practices are: 1. Educate for empowerment. 2. Know how to talk about race. 3. Capture the unseen. 4. Resist telling a simple story. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1028

S1028 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð SENATE February 25, 1998 As the nation prepares to officially cele- As we celebrate the Martin Luther King and experience in responsible financial brate the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Lu- Holiday on Monday, and as we honor James management. ther King, Jr., it is also fitting that we join Farmer with the Presidential Medal of Free- Dr. McKinney is well known in local the President in recognizing one of the great dom, let us vow to continue to learn. If we and national church circles. He has soldiers and leaders of the Civil Rights truly believe in the idea of the beloved com- Movement. In the 1940's, while still in his munity and an interracial democracy, we served as a leader of the American Bap- early twenties, James Farmer was already cannot give up. As a nation and a people, we tist Convention USA. He was the first leading some of the earliest nonviolent dem- must join together and strive towards laying African American president of the onstrations and sit-ins in the nation, over a down the burden of race. And we must follow Church Council of Greater Seattle from decade before nonviolent tactics became a in the footsteps of a courageous leader, to 1965 to 1967. He has served as Advisor vehicle for the modern Civil Rights Move- whom, with the Presidential Medal of Free- on Racism to the World Council of ment in the South. dom, we can finally say: thank you, James Churches, and as a representative to Early in his academic career, James Farm- Farmer.· er became interested in the Ghandian prin- WCC's Seventh Assembly. -

The Sit-In Movement by Ushistory.Org 2016

Name: Class: The Sit-In Movement By USHistory.org 2016 The Civil Rights Movement (1954-1968) was a social movement in the United States during which activists attempted to end racial segregation and discrimination against African Americans. This movement employed several different types of protests. As you read, identify the tactics that civil rights activists used to oppose racial segregation. [1] By 1960, the Civil Rights Movement had gained strong momentum. The nonviolent measures employed by Martin Luther King Jr.1 helped African American activists win supporters across the country and throughout the world. On February 1, 1960, the peaceful activists introduced a new tactic into their set of strategies. Four African American college students walked up to a whites-only lunch counter at the local Woolworth’s store in Greensboro, North Carolina, and asked for "5 – The U.S. Civil Rights Movement" by U.S. Embassy The Hague is coffee. When service was refused, the students licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0 sat patiently. Despite threats and intimidation, the students sat quietly and waited to be served. The civil rights sit-in was born. No one participated in a sit-in of this sort without seriousness of purpose. The instructions were simple: sit quietly and wait to be served. Often the participants would be jeered and threatened by local customers. Sometimes they would be pelted with food or ketchup. Protestors did not respond when provoked by angry onlookers. In the event of a physical attack, the student would curl up into a ball on the floor and take the punishment. -

Bayard Rustin's

LGBTQ+ History Lesson Inquiry Question: How did Bayard Rustin’s identity shape his beliefs and actions? Standard: 11.10 Inquiry Question: How did Bayard Rustin’s identity shape his beliefs and actions? Sasha Guzman Social Justice Humanitas Academy Content Standards 11.10 - Students analyze the development of federal civil rights and voting rights. 4. Examine the roles of civil rights advocates (e.g., A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Thurgood Marshall, James Farmer, Rosa Parks), including the significance of Martin Luther King, Jr. 's "Letter from Birmingham Jail" and "I Have a Dream" speech. CCSS Standards: History/Social Science, Grade 11-12 • CCSS RH 11.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources connecting insights to such features as the date and origin of the gained from specific details to the text as a whole. • CCSS RH 11. 3 Evaluate various explanations for actions or events Key I a process related to history/social studies a text; determine whether earlier events caused and determine which explanation best accords with textual evidence, acknowledging where the text leaves matters uncertain. Speaking & Listening, Grade 11-12 • CCSS SL 12.3 Evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric, assessing the stance, premises, links among ideas, word choice, points of emphasis, and tone used. • W.1 Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence. Overview of Lesson In this lesson, students will examine primary sources to understand how Bayard Rustin’s identity shaped and influenced his actions as a Civil Rights leaders. -

Sitting Down to Stand up for Democracy

Sitting Down To Stand Up For Democracy Overview Students will evaluate the actions of various citizens during the Civil Rights Movement and how their actions brought about changes for society (then and now) through the examination of poetry, biographies, speeches, photographs, historical events, and civil rights philosophies. Grade 8 North Carolina Essential Standards for 8th Grade • 8.H.1: Apply historical thinking to understand the creation and development of North Carolina and the United States. • 8.H.2.1: Explain the impact of economic, political, social, and military conflicts (e.g. war, slavery, states’ rights and citizenship and immigration policies) on the development of North Carolina and the United States • 8.H.2.2: Summarize how leadership and citizen actions influenced the outcome of key conflicts in North Carolina and the United States. • 8.H.3.3: Explain how individuals and groups have influenced economic, political and social change in North Carolina and the United States. • 8.C&G.1.4: Analyze access to democratic rights and freedoms among various groups in North Carolina and the United States • 8.C&G.2.1: Evaluate the effectiveness of various approaches used to effect change in North Carolina and the United States • 8.C&G.2.2: Analyze issues pursued through active citizen campaigns for change • 8.C&G.2.3: Explain the impact of human and civil rights issues throughout North Carolina and United States history • 8.C.1.3: Summarize the contributions of particular groups to the development of North Carolina and the United States Essential Questions • In what ways were African Americans deprived of equality during the Jim Crow Era? • In what ways did citizens and engaged community members work to bring about change during the Civil Rights Movement? • Evaluate the effectiveness and/or ineffectiveness of legislation in regards to eQual rights.