Farmer, James (12 Jan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Rights Movement and the Legacy of Martin Luther

RETURN TO PUBLICATIONS HOMEPAGE The Dream Is Alive, by Gary Puckrein Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: Excerpts from Statements and Speeches Two Centuries of Black Leadership: Biographical Sketches March toward Equality: Significant Moments in the Civil Rights Movement Return to African-American History page. Martin Luther King, Jr. This site is produced and maintained by the U.S. Department of State. Links to other Internet sites should not be construed as an endorsement of the views contained therein. THE DREAM IS ALIVE by Gary Puckrein ● The Dilemma of Slavery ● Emancipation and Segregation ● Origins of a Movement ● Equal Education ● Montgomery, Alabama ● Martin Luther King, Jr. ● The Politics of Nonviolent Protest ● From Birmingham to the March on Washington ● Legislating Civil Rights ● Carrying on the Dream The Dilemma of Slavery In 1776, the Founding Fathers of the United States laid out a compelling vision of a free and democratic society in which individual could claim inherent rights over another. When these men drafted the Declaration of Independence, they included a passage charging King George III with forcing the slave trade on the colonies. The original draft, attributed to Thomas Jefferson, condemned King George for violating the "most sacred rights of life and liberty of a distant people who never offended him." After bitter debate, this clause was taken out of the Declaration at the insistence of Southern states, where slavery was an institution, and some Northern states whose merchant ships carried slaves from Africa to the colonies of the New World. Thus, even before the United States became a nation, the conflict between the dreams of liberty and the realities of 18th-century values was joined. -

Submerged Diffusion and the African-American

SUBMERGED DIFFUSION AND THE AFRICAN -AMERICAN ADOPTION OF THE GANDHIAN REPERTOIRE * Sean Chabot Amsterdam School for Social Science Research (ASSR) University of Amsterdam As a recent graduate from Howard University, James Farmer moved to Chicago in August 1941, where he found a job as race relations sec- retary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). The one thing these two institutions had in common was their close a Ynity with the Gandhian philosophy of nonviolence. On the one hand, Farmer’s mentor at Howard University, Howard Thurman, had personally met and spoken with Gandhi at his ashram, while Mordecai Johnson, the university presi- dent, was famous for his eloquent speeches on India’s nonviolent strug- gle for independence. On the other hand, as an interracial and Christian paci st organization, the FOR had long been interested in the Gandhian approach to activism. This social environment, as well as his childhood confrontations with racial bigotry in the Deep South, inspired the young Farmer to formulate a plan for adapting the Gandhian repertoire of contention to the situation faced by African-Americans. After discussing his ideas with friends and fellow activists, he wrote a memo to FOR president A.J. Muste entitled “Provisional Plans for Brotherhood Mobil- ization.” In it, Farmer proposed a Gandhian framework for ghting racial injustice in the United States: From its inception, the Fellowship has thought in terms of developing de nite, positive and e Vective alternatives to violence as a technique for resolving con ict. It has sought to translate love of God and man, on one hand, and hatred of injustice on the other, into speci c action. -

Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information

“The Top Ten” Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information (Asa) Philip Randolph • Director of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. • He was born on April 15, 1889 in Crescent City, Florida. He was 74 years old at the time of the March. • As a young boy, he would recite sermons, imitating his father who was a minister. He was the valedictorian, the student with the highest rank, who spoke at his high school graduation. • He grew up during a time of intense violence and injustice against African Americans. • As a young man, he organized workers so that they could be treated more fairly, receiving better wages and better working conditions. He believed that black and white working people should join together to fight for better jobs and pay. • With his friend, Chandler Owen, he created The Messenger, a magazine for the black community. The articles expressed strong opinions, such as African Americans should not go to war if they have to be segregated in the military. • Randolph was asked to organize black workers for the Pullman Company, a railway company. He became head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black labor union. Labor unions are organizations that fight for workers’ rights. Sleeping car porters were people who served food on trains, prepared beds, and attended train passengers. • He planned a large demonstration in 1941 that would bring 10,000 African Americans to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC to try to get better jobs and pay. The plan convinced President Roosevelt to take action. -

Howard Thurman- Monthly Meeting and Plays Violin in the Madison Com Elizabeth Yates Mcgreal

March 1, 1971 Quaker Thought and Life Today THE PHOTOGRAPH ON THE COVER Was taken in Coeur d'Alene National Forest, Idaho, by Robert Goodman. FRIENDS Another tribute to the majesty of nature is in the poem on page 136, by Eloise Ford, which echoes the message JOURNAL of Psalm 19: The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament March 1, 1971 sheweth his handywork. Day unto day uttereth speech, and night unto night sheweth Volume 17, Number 5 knowledge. Friends Journal is published the first and fifteenth of each month There is no speech or language, where their voice is not heard. (except in June, July, and Augus!, when it is published monthly) Their line is gone out through all the earth, and their words by Friends Publishing Corporation at 152-A North Fifteenth Street, Philadelphia 19102. Telephone : (215) 563-7669. to the end of the world. In them hath he set a ta~ernacle Friends Journal was established in 1955 as the successor to The for the sun. Friend (1827-1955) and Friends Intelligencer (1844-1955). Which is as a bridegroom coming out of his chamber, and ALFRED STEFFERUD, Editor rejoiceth as a strong man to run a race. JOYCE R. ENNIS, Assistant Editor MYRTLE M. WALLEN, MARGUERITE L. HORLANDER, Advertising His going forth is from the end of the heaven, and his circuit NINA I. SULLIVAN, Circulation Manager unto the ends of it: and there is nothing hid from the BOARD OF MANAGERS heat thereof. Daniel D. Test, Jr., Chairman James R. Frorer, Treasurer Mildred Binns Young, Secretary The contributors to this issue: 1967-1970: Laura Lou Brookman, Helen Buckler, Mary Roberts Calhoun, Eleanor Stabler Clarke, James R. -

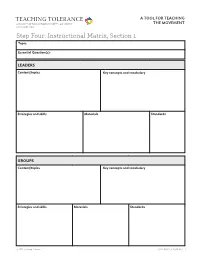

Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic: Essential Question(s): LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards GROUPS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: EVENTS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards HISTORICAL CONTEXT Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: OPPOSITION Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards TACTICS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: CONNECTIONS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 (SAMPLE) Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Martin Luther King Jr., A. -

Investigating the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Investigating the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Topic: Civil Rights History Grade level: Grades 4 – 6 Subject Area: Social Studies, ELA Time Required: 2 -3 class periods Goals/Rationale Bring history to life through reenacting a significant historical event. Raise awareness that the civil rights movement required the dedication of many leaders and organizations. Shed light on the power of words, both spoken and written, to inspire others and make progress toward social change. Essential Question How do leaders use written and spoken words to make change in their communities and government? Objectives Read, analyze and recite an excerpt from a speech delivered at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Identify leaders of the Civil Rights Movement; use primary source material to gather information. Reenact the March on Washington to gain a deeper understanding of this historic demonstration. Connections to Curriculum Standards Common Core State Standards CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.1 Quote accurately from a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text. CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.2 Determine two or more main ideas of a text and explain how they are supported by key details; summarize the text. CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.4 Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases in a text relevant to a grade 5 topic or subject area. CCSS.ELA-Literacy SL.5.6 Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and tasks, using formal English when appropriate to task and situation. National History Standards for Historical Thinking Standard 2: The student comprehends a variety of historical sources. -

Unholy Ghosts in the Age of Spirit: Identity, Intersectionality, and the Theological Horizons of Black Progress

Unholy Ghosts in the Age of Spirit: Identity, Intersectionality, and the Theological Horizons of Black Progress The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40046529 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "#$%&'!($%)*)!+#!*$,!-.,!%/!01+2+*3!! 45,#*+*'6!4#*,2),7*+%#8&+*'6!8#5!*$,!9$,%&%.+78&!:%2+;%#)!%/!<&87=!>2%.2,))! ! "!#$%%&'()($*+!,'&%&+(&#!! -.! /&')0#!1)2)'!3$00$)2%4!5'6!! (*!! 78&!/')#9)(&!:;8**0!*<!"'(%!)+#!:;$&+;&%! $+!,)'($)0!<90<$002&+(!*<!(8&!'&=9$'&2&+(%!! <*'!(8&!#&>'&&!*<! ?*;(*'!*<!@8$0*%*,8.!! $+!(8&!%9-A&;(!*<!78&!:(9#.!*<!B&0$>$*+! C)'D)'#!E+$D&'%$(.!! F)2-'$#>&4!G)%%);89%&((%! G).!HIJK! ! ! ! ! ! ! L!HIJK!/&')0#!1)2)'!3$00$)2%4!5'6!! "00!'$>8(%!'&%&'D!! ! $$! #"$$%&'('")*!+,-"$)&.!/&)0%$$)&!#(-",!12!3(45%&'6! !!!!!!!!!!!!7%&(8,!3(4(&!9"88"(4$:!;&2! ! !"#$%&'(#$)*)'+"'*#,'-.,'$/'01+2+*3'' 45,"*+*&6'4"*,2),7*+$"8%+*&6'8"5'*#,'9#,$%$.+78%':$2+;$")'$/'<%87='>2$.2,))' ! "#$%&'(%! ! ! <6%! ,"$$%&'('")*! )00%&$:! ('! '6%! "*'%&$%='")*! )0! &(=%:! >%*,%&:! $%?@(8"'A:! (*,! =8($$:! (! =)*$'&@='"-%!'6%)8)>"=(8!(==)@*'!)0!$B"&"'!"*!58(=C!16&"$'"(*"'A2!+8'6)@>6!$B"&"'!"$!(!B%&-($"-%! '&)B%!"*!+0&"=(*D+4%&"=(*!&%8">")*:!B*%@4(')8)>A!"$!4"$$"*>!($!'6%)8)>"=(8!)*%+,-!"*!58(=C! -

Martin Luther King Jr January 2021

Connections Martin Luther King Jr January 2021 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PMB Administrative Services and the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Civil Rights Message from the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Administrative Services January 2021 Dear Colleagues, The life and legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., inspires me every day, particularly when the troubles of the world seem to have placed what appear to be insurmountable obstacles on the path to achieving Dr. King’s vision. Yet I know that those obstacles will eventually melt away when we focus our hearts and minds on finding solutions together. While serving as leaders of the civil rights movement, Dr. and Mrs. King raised their family in much the same way my dear parents raised my brothers and myself. It gives me comfort to know that at the end of the day, their family came together in love and faith the same way our family did, grateful for each other and grateful knowing the path ahead was illuminated by a shared dream of a fair and equitable world. This issue of Connections begins on the next page with wise words of introduction from our collaborative partner, Erica White-Dunston, Director of the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Civil Rights. Erica speaks eloquently of Dr. King’s championing of equity, diversity and inclusion in all aspects of life long before others understood how critically important those concepts were in creating and sustaining positive outcomes. I hope you find as much inspiration and hope within the pages of this month’s Connections magazine as I did. -

This Worldwide Struggle: the International Roots Of

Bayard Rustin with Jawaharlal Nehru, 1948, Fellowship of Reconciliation Archives. August 7, 2017 · 7:30-9:00 pm · The Barn at Pendle Hill This Worldwide Struggle: The International Roots of the Civil Rights Movement A First Monday Lecture by Sarah Azaransky Sarah Azaransky will share insights from her groundbreaking new FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC book, This Worldwide Struggle: The International Roots of the Civil PLEASE REGISTER IN ADVANCE AT Rights Movement (Oxford, June 2017), which examines a network of WWW.PENDLEHILL.ORG black Americans who looked abroad and to other religious traditions TO ENSURE SEATING OR for ideas and practices that could transform American democracy. FOR LIVESTREAMING Decades before the Civil Rights movement burst into the news, black Americans had traveled around the world to learn from independence leaders in Asia and Africa. People in this seminal group met with Mohandas Gandhi in the 1930s and 1940s, later to become mentors and advisors to Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Learn about these living links connecting two of the 20th century giants of nonviolent direct action for overcoming injustice. You will find that the personal friendships and professional collaborations among Howard Thurman, Bayard Rustin, James Farmer, Benjamin Mays, and Pauli Murray hold valuable lessons for movement building today. Sarah Azaransky stayed at Pendle Hill on numerous BOOK SALES AND SIGNING occasions while researching and writing this book, and FOLLOWING THE LECTURE several prominent figures in her book also spent time at Pendle Hill. A graduate of Swarthmore College, Harvard Divinity School, and the University of Virginia, Sarah now teaches courses in social ethics about race and sexualities and their intersections at Union Theological Seminary. -

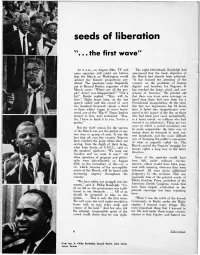

The First Wave

seeds of liberation " ... the first ",ave" At 9 a.m., on August 28th, TV and The night beforehand, Randolph had news reporters still could not believe announced that the basic objective of that the March on Washington would the March had already been achieved: achieve the historic proportions pre• "It has focused the attention of the dicted. The questions most frequently country on the problems of human put to Bayard Rustin, organizer of the dignity and freedom for Negroes. It March, were: "Where are all the peo• has reached the heart, mind, and con• ple ? Aren't you disappointed?" "Not a science of America." He pointed out' bit," Rustin replied. "They will be that there was more news coverage on here." Eight hours later, as the last hand than there had ever been for a speech ended and the crowd of over Presidential inauguration. At the time, two hundred thousand (about a third this fact was impressive, but 24 hours of them white) began to move home• later it faded into insignificance com• ward, one of the "Big 6" Negro leaders pared to the impact of the day on those turned to him and exclaimed: "Rus• who had taken part (and, undoubtedly, tin, I have to hand it to you. You're a to a lesser extent, on millions who had genius." viewed it on television). There are two ways in which a social revolution can But the chief reason for the success be made respectable: the false way of of the March was not the genius of any toning down its demands to meet cur• one man or group of men. -

Inspired by Gandhi and the Power of Nonviolence: African American

Inspired by Gandhi and the Power of Nonviolence: African American Gandhians Sue Bailey and Howard Thurman Howard Thurman (1899–1981) was a prominent theologian and civil rights leader who served as a spiritual mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr. Sue Bailey Thurman, (1903–1996) was an American author, lecturer, historian and civil rights activist. In 1934, Howard and Sue Thurman, were invited to join the Christian Pilgrimage of Friendship to India, where they met with Mahatma Gandhi. When Thurman asked Gandhi what message he should take back to the United States, Gandhi said he regretted not having made nonviolence more visible worldwide and famously remarked, "It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world." In 1944, Thurman left his tenured position at Howard to help the Fellowship of Reconciliation establish the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco. He initially served as co-pastor with a white minister, Dr. Alfred Fisk. Many of those in congregation were African Americans who had migrated to San Francisco for jobs in the defense industry. This was the first major interracial, interdenominational church in the United States. “It is to love people when they are your enemy, to forgive people when they seek to destroy your life… This gives Mahatma Gandhi a place along side all of the great redeemers of the human race. There is a striking similarity between him and Jesus….” Howard Thurman Source: Howard Thurman; Thurman Papers, Volume 3; “Eulogy for Mahatma Gandhi:” February 1, 1948; pp. 260 Benjamin Mays (1894–1984) -was a Baptist minister, civil rights leader, and a distinguished Atlanta educator, who served as president of Morehouse College from 1940 to 1967. -

Civil Rights Done Right a Tool for Teaching the Movement TEACHING TOLERANCE

Civil Rights Done Right A Tool for Teaching the Movement TEACHING TOLERANCE Table of Contents Introduction 2 STEP ONE Self Assessment 3 Lesson Inventory 4 Pre-Teaching Reflection 5 STEP TWO The "What" of Teaching the Movement 6 Essential Content Coverage 7 Essential Content Coverage Sample 8 Essential Content Areas 9 Essential Content Checklist 10 Essential Content Suggestions 12 STEP THREE The "How" of Teaching the Movement 14 Implementing the Five Essential Practices 15 Implementing the Five Essential Practices Sample 16 Essential Practices Checklist 17 STEP FOUR Planning for Teaching the Movement 18 Instructional Matrix, Section 1 19 Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Sample 23 Instructional Matrix, Section 2 27 Instructional Matrix, Section 2 Sample 30 STEP FIVE Teaching the Movement 33 Post-Teaching Reflection 34 Quick Reference Guide 35 © 2016 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT // 1 TEACHING TOLERANCE Civil Rights Done Right A Tool for Teaching the Movement Not long ago, Teaching Tolerance issued Teaching the Movement, a report evaluating how well social studies standards in all 50 states support teaching about the modern civil rights movement. Our report showed that few states emphasize the movement or provide classroom support for teaching this history effectively. We followed up these findings by releasingThe March Continues: Five Essential Practices for Teaching the Civil Rights Movement, a set of guiding principles for educators who want to improve upon the simplified King-and-Parks-centered narrative many state standards offer. Those essential practices are: 1. Educate for empowerment. 2. Know how to talk about race. 3. Capture the unseen. 4. Resist telling a simple story.