Status of Sea Turtle Conservation in Fiji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TROPICAL CYCLONE WINSTON SITUATION REPORT 30 of 26/02/2016

NATIONAL EMERGENCY OPERATION CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE WINSTON SITUATION REPORT 30 of 26/02/2016 This Situation Report is issued by the National Emergency Operation Centre and covers the period from 0800 hours to 1600hours on 26/02/2016. The purpose of this report is to provide the update on the current operations undertaken after TC Winston. 1. STATUS SUMMARY EVENT REMARKS TOTAL CENTRAL WEST EAST NORTH TOTAL Death(s) 9 11 20 2 42 Missing - - - - - Hospitalised 5 17 7 4 33 Injured 24 24 68 10 126 Evacuation 160 339 335 101 935 Centres Evacuees 13,282 33,963 6999 6095 60,339 2. WEATHER OUTLOOK NEOC SITREP 28 / 1 6 P a g e 1 | 29 Issued from the National Weather Forecasting Centre Nadi at 2.30 pm on Friday the 26th of February 2016 A strong wind warning remains in force for Kadavu passage, southern Koro sea and southern Lau waters. Situation: A weak of trough of low pressure with clouds and showers remains low moving over the eastern part of Fiji. It is expected to gradually move west wards and affect the rest of the group till later today. Meanwhile a moist north east wind flow prevails over Fiji. Forecast to midnight for Fiji waters for Kadavu passage southern Koro sea and southern Lau waters, north east winds 20 to 25 knots. Rough seas. Moderate north east swells. Poor visibility in areas of showers and thunderstorm. Further outlook:: East to north east winds 20 to 25 knots, Rough seas. For the rest of Fiji waters north to north east winds, 15 to 20 knots, moderate to rough seas. -

BA Amendments

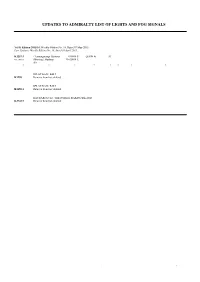

UPDATES TO ADMIRALTY LIST OF LIGHTS AND FOG SIGNALS Vol K Edition 2015/16. Weekly Edition No. 19, Dated 07 May 2015. Last Updates: Weekly Edition No. 18, dated 30 April 2015. K1257·3 - Tanjungwangi Harbour 8 08·09 S Q(4)W 8s 10 ID, , 4041A (Meneng). Harbour 114 24·08 E (ID) ******** SELAT BALI. BALI K1258 Remove from list; deleted SELAT BALI. BALI K1258·1 Remove from list; deleted HAURAKI GULF. THE NOISES. RAKINO ISLAND K3742·2 Remove from list; deleted 5.9 Wk19/15 VI 5.+4,$ -/ /TAKHRGDC6J +@RS4OC@SDR6DDJKX$CHSHNM-N C@SDC OQHK 1 # 1!$ ".-2 / &$ !1 9(+ ADKNV/NMS@/HQ@ITA@+S (MRDQS ,@MNDK+T§R+S%KN@S!% mț̦2mț̦6 m 3 !Q@YHKH@M-NSHBD12#1 43., 3("(#$-3(%(" 3(.-2823$, (2 / &$ "'(- ADKNV'DMFWHM6QDBJ (MRDQS 'NMF8T@M mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 5HQST@K ENQLDQTOC@SD "GHMDRD-NSHBD12#1 / &$ "'(- ADKNV'T@MFYD8@MF+S5DRRDK (MRDQS 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR 1D@K 'T@QTMCH@M&@MF+S!TNX-N mț̦-mț̦$ !QN@CB@RSRDUDQXLHMTSDR -

Data Structure

Data structure – Water The aim of this document is to provide a short and clear description of parameters (data items) that are to be reported in the data collection forms of the Global Monitoring Plan (GMP) data collection campaigns 2013–2014. The data itself should be reported by means of MS Excel sheets as suggested in the document UNEP/POPS/COP.6/INF/31, chapter 2.3, p. 22. Aggregated data can also be reported via on-line forms available in the GMP data warehouse (GMP DWH). Structure of the database and associated code lists are based on following documents, recommendations and expert opinions as adopted by the Stockholm Convention COP6 in 2013: · Guidance on the Global Monitoring Plan for Persistent Organic Pollutants UNEP/POPS/COP.6/INF/31 (version January 2013) · Conclusions of the Meeting of the Global Coordination Group and Regional Organization Groups for the Global Monitoring Plan for POPs, held in Geneva, 10–12 October 2012 · Conclusions of the Meeting of the expert group on data handling under the global monitoring plan for persistent organic pollutants, held in Brno, Czech Republic, 13-15 June 2012 The individual reported data component is inserted as: · free text or number (e.g. Site name, Monitoring programme, Value) · a defined item selected from a particular code list (e.g., Country, Chemical – group, Sampling). All code lists (i.e., allowed values for individual parameters) are enclosed in this document, either in a particular section (e.g., Region, Method) or listed separately in the annexes below (Country, Chemical – group, Parameter) for your reference. -

Zeszyt 10. Morza I Oceany

Uwaga: Niniejsza publikacja została opracowana według stanu na 2008 rok i nie jest aktualizowana. Zamieszczony na stronie internetowej Komisji Standaryzacji Nazw Geograficznych poza Granica- mi Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej plik PDF jest jedynie zapisem cyfrowym wydrukowanej publikacji. Wykaz zalecanych przez Komisję polskich nazw geograficznych świata (Urzędowy wykaz polskich nazw geograficznych świata), wraz z aktualizowaną na bieżąco listą zmian w tym wykazie, zamieszczo- ny jest na stronie internetowej pod adresem: http://ksng.gugik.gov.pl/wpngs.php. KOMISJA STANDARYZACJI NAZW GEOGRAFICZNYCH POZA GRANICAMI RZECZYPOSPOLITEJ POLSKIEJ przy Głównym Geodecie Kraju NAZEWNICTWO GEOGRAFICZNE ŚWIATA Zeszyt 10 Morza i oceany GŁÓWNY URZĄD GEODEZJI I KARTOGRAFII Warszawa 2008 KOMISJA STANDARYZACJI NAZW GEOGRAFICZNYCH POZA GRANICAMI RZECZYPOSPOLITEJ POLSKIEJ przy Głównym Geodecie Kraju Waldemar Rudnicki (przewodniczący), Andrzej Markowski (zastępca przewodniczącego), Maciej Zych (zastępca przewodniczącego), Katarzyna Przyszewska (sekretarz); członkowie: Stanisław Alexandrowicz, Andrzej Czerny, Janusz Danecki, Janusz Gołaski, Romuald Huszcza, Sabina Kacieszczenko, Dariusz Kalisiewicz, Artur Karp, Zbigniew Obidowski, Jerzy Ostrowski, Jarosław Pietrow, Jerzy Pietruszka, Andrzej Pisowicz, Ewa Wolnicz-Pawłowska, Bogusław R. Zagórski Opracowanie Kazimierz Furmańczyk Recenzent Maciej Zych Komitet Redakcyjny Andrzej Czerny, Joanna Januszek, Sabina Kacieszczenko, Dariusz Kalisiewicz, Jerzy Ostrowski, Waldemar Rudnicki, Maciej Zych Redaktor prowadzący Maciej -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Tui Tai Expeditions One of the World's Only Truly All-Inclusive

tui tai expeditions We hope you’ll join us for the trip of a lifetime, during which you’ll visit remote beaches, snor- kel over incredible reefs, kayak to local villages, and experience the most breathtaking locations across Northern Fiji. The Tui Tai Expeditions takes guests to places they never imagined, the natural beauty of Fiji, and the kindness and warmth of the Fijian people. Tui Tai Expeditions is the premier adventure experience in the South Pacific. one of the world’s only truly all-inclusive expeditions When you’re enjoying a luxury-adventure expedition on Tui Tai, you don’t ever have to think about the details of extra charges because there aren’t any. We’ve designed our service to be All-inclusive. Not “all inclusive” as some use the term, followed by a bunch of fine print explaining what isn’t included. We mean that everything is included: every service, mixed drink, glass of wine or beer, every meal, all scuba diving (even dive courses), snorkeling, kayaking, spa treatments - everything. Once you board Tui Tai, the details are in our hands, and your only responsibility is to have the experience of a lifetime. “World’s Sexiest Cruise Ships” Conde Nast luxury that doesn’t get adventure that doesn’t pacific cultural triangle rabi island Micronesian people, originally in the way of adventure get in the way of luxury Tui Tai is the only luxury-adventure ship oper- from Banaba in equatorial Kiribati. The word luxury can be defined in many ways. Like luxury, adventure can be defined many ating in the Pacific Cultural Triangle, providing Settled on Rabi Island in Fiji on On Tui Tai, luxury means that everything has ways. -

EXPEDITIONS Summary Calendar Month by Month

EXPEDITIONS Summary calendar month by month WINTER 2018/2019 SEPTEMBER DECEMBER MARCH 2018 DAYS SHIP VOYAGE EMBARK/DISEMBARK 2018 DAYS SHIP VOYAGE EMBARK/DISEMBARK 2019 DAYS SHIP VOYAGE EMBARK/DISEMBARK AFRICA & THE INDIAN OCEAN GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS 28th 14 9822 Colombo > Mahé 01st 7 8848 North Central Itinerary 02nd 7 8909 Western Itinerary 08th 7 8849 Western Itinerary 09th 7 8910 North Central Itinerary 16th 7 Western Itinerary OCTOBER 15th 7 8850 North Central Itinerary 8911 23rd 7 8912 North Central Itinerary 2018 DAYS SHIP VOYAGE EMBARK/DISEMBARK 22nd 7 8851 Western Itinerary 30th 7 8913 Western Itinerary GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS 29th 7 8852 North Central Itinerary ASIA 06th 7 8840 North Central Itinerary ANTARCTICA 05th 15 9905 Yangon > Benoa (Bali) 13th 7 Western Itinerary 8841 02nd 10 1827 Ushuaia Roundtrip 20th 16 9906 Benoa (Bali) > Darwin 20th 7 8842 North Central Itinerary 07th 10 7824 Ushuaia Roundtrip 27th 7 8843 Western Itinerary ANTARCTICA 12th 10 1828 Ushuaia Roundtrip 07th 21 1907 Ushuaia > Cape Town AFRICA & THE INDIAN OCEAN 17th 18 7825 Ushuaia Roundtrip CENTRAL & SOUTH AMERICA 12th 11 9823 Mahé Roundtrip 22nd 15 1829 Ushuaia Roundtrip 07th 9 7905 Valparaíso > Easter Island CENTRAL & SOUTH AMERICA AFRICA & THE INDIAN OCEAN SOUTH PACIFIC ISLANDS 03th 12 1822 Nassau > Colon 13th 6 9828A Durban > Maputo 16th 14 7906 Easter Island > Papeete (Tahiti) 15th 11 1823 Colon > Callao (Lima) 30th 13 Papeete (Tahiti) > Lautoka 19th 17 9829 Maputo > Mahé 7907 26th 16 1824 Callao (Lima) > Punta Arenas AFRICA & THE INDIAN -

Current and Future Climate of the Fiji Islands

Rotuma eef a R Se at re Ahau G p u ro G a w a Vanua Levu s Bligh Water Taveuni N a o Y r th er Koro n La u G ro Koro Sea up Nadi Viti Levu SUVA Ono-i-lau S ou th er n L Kadavu au Gr South Pacific Ocean oup Current and future climate of the Fiji Islands > Fiji Meteorological Service > Australian Bureau of Meteorology > Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Fiji’s current climate Across Fiji the annual average temperature is between 20-27°C. Changes Fiji’s climate is also influenced by the in the temperature from season to season are relatively small and strongly trade winds, which blow from the tied to changes in the surrounding ocean temperature. east or south-east. The trade winds bring moisture onshore causing heavy Around the coast, the average night- activity. It extends across the South showers in the mountain regions. time temperatures can be as low Pacific Ocean from the Solomon Fiji’s climate varies considerably as 18°C and the average maximum Islands to east of the Cook Islands from year to year due to the El Niño- day-time temperatures can be as with its southern edge usually lying Southern Oscillation. This is a natural high as 32°C. In the central parts near Fiji (Figure 2). climate pattern that occurs across of the main islands, average night- Rainfall across Fiji can be highly the tropical Pacific Ocean and affects time temperatures can be as low as variable. On Fiji’s two main islands, weather around the world. -

Leaving Place, Restoring Home Enhancing the Evidence Base on Planned Relocation Cases in the Context of Hazards, Disasters, and Climate Change

LEAVING PLACE, RESTORING HOME ENHANCING THE EVIDENCE BASE ON PLANNED RELOCATION CASES IN THE CONTEXT OF HAZARDS, DISASTERS, AND CLIMATE CHANGE By Erica Bower & Sanjula Weerasinghe March 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable support and feedback of several individuals and organizations in the preparation of this report. This includes members of the reference group: colleagues at the Platform on Disaster Displacement (Professor Walter Kälin, Sarah Koeltzow, Juan Carlos Mendez and Atle Solberg); members of the Platform on Disaster Displacement Advisory Committee including Bruce Burson (Independent Consultant), Beth Ferris (Georgetown University), Jane McAdam (UNSW Sydney) and Matthew Scott (Raoul Wallenberg Institute); colleagues at the International Organization for Migration (Alice Baillat, Pablo Escribano, Lorenzo Guadagno and Ileana Sinziana Puscas); colleagues at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (Florence Geoffrey, Isabelle Michal and Michelle Yonetani); and colleagues at GIZ (Thomas Lennartz and Felix Ries). The authors also wish to acknowledge the assistance of Julia Goolsby, Sophie Offner and Chloe Schalit. This report has been carried out under the Platform on Disaster Displacement Work Plan 2019-2022 with generous funding support from the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs of Switzerland. It was co-commissioned by the Platform on Disaster Displacement and the Andrew & Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law at UNSW Sydney. Any feedback or questions about this report may -

Fijian Frontiers Richard Smith © 2015

destination report | kadavu | fiji FIJIAN FRONTIERS RICHARD SMITH © 2015 FIJI IS CONSIDERED BY MANY AS THE SOFT CORAL CAPITAL OF THE WORLD, BUT THIS DIVERSE NATION HAS MUCH MORE TO OFFER THAN SOFT CORALS ALONE. I GUIDED A GROUP OF DIVERS TO KADAVU ISLAnd’S REMOTE SOUTH EASTERN COAST TO SHARe Fiji’S INDIGENOUS MARINE LIFE, STUNNING REEFS DOMINATED BY DIVERSE HARD CORALS, AND TO EXPERIENCE SOME RICH LOCAL CULTURE. rom the capital Nadi, we headed to found in Fiji’s waters almost immediately Kadavu southwest of the main island of on descent, I had high hopes for finding FViti Levu. The 45 minute flight in a 12 some of the others before we left. After a seater plane offered amazing views of the second great dive at Manta Reef and a aquamarine reefs below and the rainforest fleeting visit by a pure black ‘Darth Vader’ wilderness on Kadavu. This is one of the manta we headed back to the resort to try few great stands of forest remaining in the out the house reef. island group and it harbours a wealth of globally important terrestrial animal and Closer to home The resort ‘taxi service’ plant populations, as well as fantastic reefs. dropped us along the reef and we swam back to the resort during the dive. The After landing, a quick hop in a truck, guides explained the highlights and told a couple of boats made the hour long us to swim slowly to appreciate the smaller journey to the resort through endless inhabitants. There were many nudibranchs forests which tumbled into the coral fringed to keep us enthralled for the whole dive. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

South Pacific Islands Expedition Cruise

PAPEETE TO LAUTOKA: SOUTH PACIFIC ISLANDS EXPEDITION CRUISE Join us to look for the Pearls of the Pacific. Starting in Tahiti, Silver Explorer will sail through Polynesia via the Cook Islands, Niue and Tonga and will visit several island gems in Fiji. Discover black pearls and underwater wonders, and explore blue lagoons and raised coral islands. Swim with rays and sharks, watch for dolphins and look for seabird colonies on isolated islands in some of Polynesia’s and Melanesia’s best and least known lagoons, or relax on beautiful beaches. Interact with local communities and experience the legendary friendliness of the Pacific Islanders. Throughout the voyage, learn about the history, geology, wildlife and botany of these locations from lecture presentations offered by your knowledgeable onboard Expedition Team. ITINERARY Day 1 PAPEETE (TAHITI) Papeete will be your gateway to the tropical paradise of French Polynesia, where islands fringed with gorgeous beaches and turquoise ocean await to soothe the soul. This spirited city is the capital of French Polynesia, and serves as a superb base for onward exploration of Tahiti – an island of breathtaking landscapes and oceanic vistas. Wonderful lagoons of crisp, clear water beg to be snorkelled, stunning black beaches and blowholes pay tribute to the island's volcanic heritage, and lush green mountains beckon you inland on adventures, as you explore extraordinary Tahiti. Day 2 BORA BORA (SOCIETY ISLANDS) 01432 507 280 (within UK) [email protected] | small-cruise-ships.com Simply saying the name Bora Bora is usually enough to induce ashore, the whole community generally turns out to meet gasps of jealousy, as images of milky blue water, sparkling visitors as it is a rare occurrence.