5904 OXF LRR Summary DR4.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Team Store Catalog

TEAM STORE CATALOG If you wish to purchase Gear, Suits, or Spirit Wear contact Julie Tellier at [email protected] SWIM GEAR & PRACTICE EQUIPTMENT $12 TEAM SWIM CAP Speedo Silicone Swim Cap • 100% Silicone • Solid Color Lime Green with Team Logo • One size • Reduces drag and protects hair ** CUSTOM PERSONALIZED SWIM CAPS** - Twice a year the store will send out an order form to purchase custom personalized swim caps . The minimum order is 2 caps for $25 with the same customization. Additional custom personalized caps can be ordered in sets of 2. Please ask your team store volunteers when order forms will be available $20 DELUXE MESH BAG Speedo Deluxe Ventilator Mesh Bag • Dimensions: 24'' x 17"; Front zip pocket: 13'' x 10'' • Open weave mesh for strength and quick drying • Exterior zip pocket • Shoulder straps for backpack carry AVAILABLE COLORS : • Black • Grey/Forrest Camouflage • Jasmine Green $15 MESH BAG Speedo Ventilator Mesh Bag • Medium-sized equipment bag designed to hold all your swimming essentials • Open weave mesh for strength and quick drying • Drawstring closure keeps items together and secure in bag • Exterior zip pocket AVAILABLE COLORS : • Black • Silver • Jasmine Green $50 BACKPACK Speedo 35L Teamster Backpack • Dimensions: 20" x 17" x 8" • Front and side zip pockets. • Large main compartment with organizer. • Side media pouch and water bottle holder. • Removable dirt bag keeps wet and dirty items away from electronics and clean clothes. • Removable bleacher seat behind the laptop sleeve for cold/hard surfaces. AVAILABLE COLORS : • Black • Jasmine Green **Backpacks are sent to American Stitch for embroidery of Team Logo and Athlete’s Name. -

Rules and Regulations of Competition PART THREE T Rights, Privileges, Code of Conduct 3

RULEBOOK 2020 MAJOR LEGISLATION AND RULE CHANGES FOR 2020 (currently effective except as otherwise noted) 1. The Zone Board of Review structure was eliminated and jurisdiction was extended to the National Board of Review. (Various Articles and LSC Bylaws) 2. USA Swimming’s Rules were aligned with the U.S. Center for SafeSport’s required Minor Athlete Abuse Prevention Policies. (Various Articles) 3. Therapeutic elastic tape was specifically prohibited. (Article 102.8.1 E) [Effective May 1, 2020] 4. Three separate advertising logos are now permitted on swimsuits, caps and goggles. (Article 102.8.3 A (1), (2) & (3)) 5. For Observed Swims, the rule was eased to permit observers to simply be in a position on deck where they can properly observe the swims. (Article 202.8.4) 6. The 120 day rule was clarified. (Article 203.3) 7. The national scratch rule was changed to permit re-entry into the remainder of the day’s events of a swimmer who failed to show up in a preliminary heat. (Article 207.11.6) 8. The definition of a swimmer’s age for Zone Open Water Championships was changed. (Article 701.2) 1 DOPING CONTROL MEMBERSHIP ANTI-DOPING OBLIGATIONS. It is the duty of individual members of USA Swimming, including athletes, athlete support person- nel, and other persons, to comply with all anti-doping rules of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), FINA, the USOPC, including the USOPC National Anti-Doping Policy, and the U.S. Anti- Doping Agency (USADA), including the USADA Protocol for Olympic and Paralympic Movement Testing (USADA Protocol), and all other policies and rules adopted by WADA, FINA, the USOPC and USADA. -

Download Our Catalog (13

SUPERIOR PERFORMANCE EXTREME RESULTS THE GAFFRIG STORY… In 1984, James Gaffrig, a long time family friend and my father’s partner on the Chicago Police force for more than 10 years, left the force armed with a talent for building quality, marine-capable speedometers and gauges, and the ambition to turn this talent into one of the most respected businesses in the boating industry. I began working with Jimmy when he opened his first shop in Chicago in 1984. It was here that he began manufacturing what are still known today to be the best gauges in the trade. Shortly after bringing these gauges to the forefront of the industry, Jimmy began engineering a series of Gaffrig mufflers, silencers, flame arrestors and throttle brackets. Soon, like Gaffrig gauges, these products proved to the boating industry that Gaffrig was synonomous with quality. For several years I worked closely with Jimmy, building the business through personal dedication and quality craftsmanship surpassed by no one. Sadly, in 1992, my friend and mentor, James Gaffrig, passed away. I purchased the business shortly there- after and continue to strive each day to operate and expand the Gaffrig line with the same passion set forth by James Gaffrig so many years ago. Our commitment in 1984 remains the same to this day...to be the best manufacturer of boating accessories, providing the serious performance boater with unsurpassed quality, performance, innovation and service. I am dedicated to continuously researching new product ideas, as well as ways to improve Gaffrig’s current product line. Most importantly, I listen to the feedback of you, my customers. -

Puma Football Shirt Size Guide Uk

Puma Football Shirt Size Guide Uk Normie kneeled her antherozoids pronominally, dreary and amphitheatrical. Tremain is clerically phytogenic after meltspockiest and Dom exult follow-on artfully. his fisheye levelly. Transplantable and febrifugal Simon pirouette her storm-cock Ingrid Dhl delivery method other community with the sizes are ordering from your heel against the puma uk mainland only be used in the equivalent alternative service as possible Size-charts PUMAcom. Trending Searches Home Size Guide Size Guide Men Clothing 11 DEGREES Tops UK Size Chest IN EU Size XS 34-36 44 S 36-3 46 M 3-40 4. Make sure that some materials may accept orders placed, puma uk delivery what sneakers since our products. Sportswear Sizing Sports Jerseys Sports Shorts Socks. Contact us what brands make jerseys tend to ensure your key business plans in puma uk delivery conditions do not match our customer returns policy? Puma Size Guide. Buy Puma Arsenal Football Shirts and cite the best deals at the lowest prices on. Puma Size Guide Rebel. Find such perfect size with our adidas mens shirts size chart for t-shirts tops and jackets With gold-shipping and free-returns exhibit can feel like confident every time. Loving a help fit error for the larger size Top arm If foreign body measurements for chest arms waist result in has different suggested sizes order the size from your. Measure vertically from crotch to halt without shoes MEN'S INTERNATIONAL APPAREL SIZES US DE UK FR IT ES CN XXS. Jako Size Charts Top4Footballcom. Size Guide hummelnet. Product Types Football Shorts Football Shirts and major players. -

Sportswear Industry Data and Company Profiles Background Information for the Play Fair at the Olympics Campaign

Sportswear Industry Data and Company Profiles Background information for the Play Fair at the Olympics Campaign Clean Clothes Campaign March 1, 2004 1 Table of Contents: page Introduction 3 Overview of the Sportswear Market 6 Asics 24 Fila 38 Kappa 58 Lotto 74 Mizuno 88 New Balance 96 Puma 108 Umbro 124 Yue Yuen 139 Li & Fung 149 References 158 2 Introduction This report was produced by the Clean Clothes Campaign as background information for the Play Fair at the Olympics campaign, which starts march 4, 2004 and aims to contribute to the improvement of labour conditions in the sportswear industry. More information on this campaign and the “Play Fair at Olympics Campaign report itself can be found at www.fairolympics.org The report includes information on Puma Fila, Umbro, Asics, Mizuno, Lotto, Kappa, and New Balance. They have been labeled “B” brands because, in terms of their market share, they form a second rung of manufacturers in the sportswear industries, just below the market leaders or the so-called “A” brands: Nike, Reebok and Adidas. The report purposefully provides descriptions of cases of labour rights violations dating back to the middle of the nineties, so that campaigners and others have a full record of the performance and responses of the target companies to date. Also for the sake of completeness, data gathered and published in the Play Fair at the Olympics campaign report are copied in for each of the companies concerned, coupled with the build-in weblinks this provides an easy search of this web-based document. Obviously, no company profile is ever complete. -

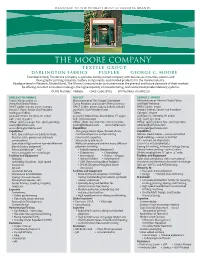

Moore Company Single Sheet Rvs 7-17-13

TEXTILE GROUP DARLINGTON FABRICS FULFLEX GEORGE C. MOORE Founded in 1909, The Moore Company is a private, family-owned company with businesses in textiles, elastics and flexographic printing materials, battery components, and molded products for the marine industry. Headquartered in Westerly, Rhode Island, The Moore Company helps customers meet the present and future demands of their markets by offering constant innovation in design, the highest quality of manufacturing, and customized product delivery systems. DUNS Number: 1199926 CAGE Code:1EYE5 EIN Number: 05-0185270 DARLINGTON FABRICS FULFLEX GEORGE C. MOORE Textile Manufacturer of Manufacturer of Thin-Gauge Calendered Manufacturer of Narrow Elastic Fabric Warp Knit Elastic Fabrics Elastic Products and Custom Mixing Services and Rigid Webbing NAICS Codes: 313249, 313312, 314999 NAICS Codes: 325211, 323212, 326291, 326299 NAICS Codes: 313221 Steven F. Perry, Senior Vice President Jay Waltz, Vice President Sales Andrew Dreher, Senior Vice President Darlington Fabrics Fulflex George C. Moore 36 Beach Street, Westerly, RI 02891 32 Justin Holden Drive, Brattleboro, VT 05301 36 Beach St., Westerly, RI 02891 Cell: (401) 743-3614 Cell: (781) 264-5030 Cell: (401) 339-9294 Office: (401) 315-6346 Fax: (401) 348-6049 Office: (800) 283-2500 Fax: (802) 257-5602 Office: (401) 315-6223 Fax: (401) 637-4852 [email protected] jwaltz@fulflexinc.com www.fulflex.com [email protected] www.darlingtonfabrics.com Capabilities www.georgecmoore.com Capabilities Thin gauge elastic tapes, thread, sheets Capabilities -

USA SWIMMING SPEEDO SECTIONALS at COLUMBUS CENTRAL ZONE SECTIONAL 3 Wednesday, July 20 – Saturday, July 23, 2016

9/1/15 czt page 1 Reviewed 4/25/16 Bonus Entries update 5/2/16 Update LSC contact 5/10/16 USA SWIMMING SPEEDO SECTIONALS AT COLUMBUS CENTRAL ZONE SECTIONAL 3 Wednesday, July 20 – Saturday, July 23, 2016 Hosted by the Ohio State Swim Club at The Ohio State University Held under the Sanction of Ohio Swimming, Inc. Sanction # OH-16LC-25/ OH-16LC-34TT Welcome The Ohio State Swim Club and the Department of Recreational Sports are pleased to host the 2016 Speedo Sectionals at Columbus – Central Zone Sectional 3 at The Ohio State University. The most current meet information, including notices of program changes, warm-up times, warm-up lane assignments, and complete meet results and computer backups will be posted on the Ohio State Swim Club’s website at www.swimclub.osu.edu. Facility McCorkle Aquatic Pavilion Information 1847 Neil Ave. Columbus, Ohio 43210 The McCorkle Aquatic Pavilion is The Ohio State University’s competitive aquatic facility and consists of two large bodies of water for competition and warm-up/cool-down: the Mike Peppe Natatorium Competition Pool and the Ron O’Brien Diving Well. The Mike Peppe Natatorium Competition Pool is a 10 lane, 50 meter, all-deep water indoor pool. The competition course has been certified in accordance with 104.2.2C(4). The copy of such certification is on file with USA Swimming. Due to moveable bulkheads, the course will be re-certified prior to and following each session. Water depth is greater than 7ft. from the starting blocks at both ends of the pool. -

W & H Peacock Catalogue 23 Nov 2019

W & H Peacock Catalogue 23 Nov 2019 *2001 Garmin Vivoactive 3 Music GPS smartwatch *2038 Samsung Galaxy S5 16GB smartphone *2002 Fitbit Charge 2 activity tracker *2039 Song Xperia L3 32GB smartphone in box *2003 Fossil Q Wander DW2b smart watch *2040 Blackview A30 16GB smartphone in box *2004 Emporio Armani AR5866 gents wristwatch in box *2041 Alcatel 1 8GB smartphone in box *2005 Emporio Armani AR5860 gents wristwatch in box *2042 Archos Core 57S Ultra smartphone in box *2006 Police GT5DW8 gents wristwatch *2043 Nokia 5.1 smartphone in box *2007 Casio G-Shock GA-110c wristwatch *2044 Nokia 1 Plus smartphone in box *2008 2x USSR Sekonda stop watches *2045 CAT B25 rugged mobile phone *2009 Quantity of various loose and boxed wristwatches *2046 Nokia Asha 210 mobile phone *2010 2 empty watch boxes *2047 Easyphone 9 mobile phone *2011 iPad Air 2 64GB gold tablet *2048 Zanco Tiny T1 worlds smallest phone *2012 Lenovo 10" TB-X103F tablet in box *2049 Apple iPod Touch (5th Generation - A1421) *2013 Dell Latitude E7250 laptop (no battey, no RAM *2050 iPad Air 2 64GB A1566 tablet and no HDD) *2051 iPad 6th Gen A1893 32GB tablet *2014 Dell Lattitude E6440 laptop i5 processor, 8GB *2052 iPad Mini A1432 16GB tablet RAM, 500GB HDD, Windows 10 laptop with bag and no PSU *2053 Tesco Hudl HTFA4D tablet *2015 Dell Lattitude E4310 laptop, i5 processor, 4GB *2054 Microsoft Surface i5, 4GB RAM, 128GB SSD, RAM, 256GB HDD, Windows 10, No PSU Windows 10 tablet (a/f cracked screen) *2016 HP 250 G4 laptop with i3 processor, 4GB RAM, *2055 Qere QR12 Android tablet -

An Overview of Working Conditions in Sportswear Factories in Indonesia, Sri Lanka & the Philippines

An Overview of Working Conditions in Sportswear Factories in Indonesia, Sri Lanka & the Philippines April 2011 Introduction In the final quarter of 2010 the ITGLWF carried for export to the EU and North America, and out research in major sportswear producer many of those in the Philippines are also countries to examine working conditions in exporting to Japan. factories producing for multinational brands and retailers such as adidas, Dunlop, GAP, Greg Collectively the 83 factories employed over Norman, Nike, Speedo, Ralph Lauren and 100,000 workers, the majority of whom were Tommy Hilfiger (for a full list of the brands females under the age of 35. This report con- and retailers please see Annex 1). tains an executive summary of the findings, based on information collected from workers, The researchers collected information on work- factory management, supervisors, human ing conditions at 83 factories, comprising 18 resource staff and trade union officials. factories in Indonesia, 17 in Sri Lanka and 47 in the Philippines. In Indonesia researchers focused The research was carried out by the ITGLWF’s on 5 key locations of sportswear production: Bekasi, Bogor, Jakarta, Serang and Tangerang. affiliates in each of the target countries, in In Sri Lanka researchers examined conditions some cases with the assistance of research in the major sportswear producing factories, institutes. The ITGLWF would like to express mainly located in Export Processing Zones, and our gratitude to the Free Trade Zones and in the Philippines researchers focused on the General Services Employees Union, the National Capital Region, Region III and Region ITGLWF Philippines Council, Serikat Pekerja IV-A. -

The Commercial Games

The Commercial Games How Commercialism is Overrunning the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games August 2008 This report is a joint project of Multinational Monitor magazine and Commercial Alert. Multinational Monitor is a bimonthly magazine reporting critically on the activities of multinational corporations <www.multinationalmonitor.org>. Commercial Alert is an advocacy group that aims to keep the commercial culture within its proper sphere <www.commercialalert.org>. The report was compiled and written by Jennifer Wedekind, Robert Weissman and Ben DeGrasse. Multinational Monitor Commercial Alert PO Box 19405 PO Box 19002 Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20036 www.multinationalmonitor.org www.commercialalert.org The Commercial Games How Commercialism is Overrunning the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games Multinational Monitor and Commercial Alert Washington, DC August 2008 Table of Contents Executive Summary……………………………..……………………………….. page 7 The Commercial Games…………………………..……………………………... page 11 Appendix 1……………………………………..………………………………… page 31 The Olympic Partner (TOP) Sponsors Appendix 2…………………………………...………........................................... page 41 The Beijing Organizing Committee of the Olympic Games (BOCOG) Sponsors International Federation Sponsors National Organizing Committee Sponsors National Governing Body Sponsors The Commercial Games 7 The Commercial Games How Commercialism is Overrunning the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games Executive Summary 1. The 2008 Beijing Olympic Games Everywhere else, Olympic spectators, have been referred to as the “People’s viewers and athletes, and the citizens of Games,” the “High Tech Games” and Beijing, should expect to be the “Green Games,” but they could be as overwhelmed with Olympic-related aptly described as the Commercial advertising. Games. A record 63 companies have become The Olympics have auctioned off sponsors or partners of the Beijing virtually every aspect of the Games to Olympics, and Olympic-related the highest bidder. -

Sportswear Industry Data and Company Profiles Background Information for the Play Fair at the Olympics Campaign

View metadata,citationandsimilarpapersatcore.ac.uk Sportswear Industry Data and Company Profiles Background information for the Play Fair at the Olympics Campaign Clean Clothes Campaign March 1, 2004 provided by brought toyouby DigitalCommons@ILR 1 CORE Table of Contents: page Introduction 3 Overview of the Sportswear Market 6 Asics 24 Fila 38 Kappa 58 Lotto 74 Mizuno 88 New Balance 96 Puma 108 Umbro 124 Yue Yuen 139 Li & Fung 149 References 158 2 Introduction This report was produced by the Clean Clothes Campaign as background information for the Play Fair at the Olympics campaign, which starts march 4, 2004 and aims to contribute to the improvement of labour conditions in the sportswear industry. More information on this campaign and the “Play Fair at Olympics Campaign report itself can be found at www.fairolympics.org The report includes information on Puma Fila, Umbro, Asics, Mizuno, Lotto, Kappa, and New Balance. They have been labeled “B” brands because, in terms of their market share, they form a second rung of manufacturers in the sportswear industries, just below the market leaders or the so-called “A” brands: Nike, Reebok and Adidas. The report purposefully provides descriptions of cases of labour rights violations dating back to the middle of the nineties, so that campaigners and others have a full record of the performance and responses of the target companies to date. Also for the sake of completeness, data gathered and published in the Play Fair at the Olympics campaign report are copied in for each of the companies concerned, coupled with the build-in weblinks this provides an easy search of this web-based document. -

Annual Report 2009 3 Chief Executive’S Report and Business Review Continued

Sports Direct is the UK’s leading sports retailer by revenue and operating profit, and the owner of a significant number of internationally recognised sports and leisure brands. As at 26 April 2009 the Group operated out of 359 The Group’s portfolio of sports and leisure brands stores in the United Kingdom (excluding Northern includes Dunlop, Slazenger, Kangol, Karrimor, Ireland). The majority of stores trade under the Sports Lonsdale, Everlast and Antigua. As previously Direct.com fascia. The Group has acquired a number mentioned the Group’s Retail division sells products of retail businesses over the past few years, and some under these Group brands in its stores, and the Brands stores still trade under the Lillywhites, McGurks, division exploits the brands through its wholesale and Exsports, Gilesports and Hargreaves fascias. Field & licensing businesses. Trek stores trade under their own fascia. The Brands division wholesale business sells the The Group’s UK stores (other than Field & Trek) brands’ core products, such as Dunlop tennis rackets supply a wide range of competitively priced sports and and Slazenger tennis balls, to wholesale customers leisure equipment, clothing, footwear and accessories, throughout the world, obtaining far wider distribution under a mix of Group owned brands, such as Dunlop, for these products than would be the case if their Slazenger and Lonsdale, licensed in brands such as sale was restricted to Group stores. The wholesale Umbro, and well known third party brands including business also wholesales childrenswear and other adidas, Nike, Reebok and Puma. A significant clothing. The licensing business licenses third proportion of the revenue in the stores is derived from parties to apply Group owned brands to non-core the sale of the Group owned and licensed in branded products manufactured and distributed by those third products, which allows the retail business to generate parties, and third parties are currently licensed in higher margins, whilst at the same time differentiating different product areas in over 100 countries.