Into the Labyrinth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian SF News 28

NUMBER 28 registered by AUSTRALIA post #vbg2791 95C Volume 4 Number 2 March 1982 COW & counts PUBLISH 3 H£W ttOVttS CORY § COLLINS have published three new novels in their VOID series. RYN by Jack Wodhams, LANCES OF NENGESDUL by Keith Taylor and SAPPHIRE IN THIS ISSUE: ROAD by Wynne Whiteford. The recommended retail price on each is $4.95 Distribution is again a dilemna for them and a^ter problems with some DITMAR AND NEBULA AWARD NOMINATIONS, FRANK HERBERT of the larger paperback distributors, it seems likely that these titles TO WRITE FIFTH DUNE BOOK, ROBERT SILVERBERG TO DO will be handled by ALLBOOKS. Carey Handfield has just opened an office in Melbourne for ALLBOOKS and will of course be handling all their THIRD MAJIPOOR BOOK, "FRIDAY" - A NEW ROBERT agencies along with NORSTRILIA PRESS publications. HEINLEIN NOVEL DUE OUT IN JUNE, AN APPRECIATION OF TSCHA1CON GOH JACK VANCE BY A.BERTRAM CHANDLER, GEORGE TURNER INTERVIEWED, Philip K. Dick Dies BUG JACK BARRON TO BE FILMED, PLUS MORE NEWS, REVIEWS, LISTS AND LETTERS. February 18th; he developed pneumonia and a collapsed lung, and had a second stroke on February 24th, which put him into a A. BERTRAM CHANDLER deep coma and he was placed on a respir COMPLETES NEW NOVEL ator. There was no brain activity and doctors finally turned off the life A.BERTRAM CHANDLER has completed his support system. alternative Australian history novel, titled KELLY COUNTRY. It is in the hands He had a tremendous influence on the sf of his agents and publishers. GRIMES field, with a cult following in and out of AND THE ODD GODS is a short sold to sf fandom, but with the making of the Cory and Collins and IASFM in the U.S.A. -

COLLEGE BOOK ART ASSOCIATION INDIANA UNIVERSITY BLOOMINGTON January 13-16, 2011

COLLEGE BOOK ART ASSOCIATION INDIANA UNIVERSITY BLOOMINGTON JANUARY 13-16, 2011 www.collegebookart.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 WELCOME 4 OFFICERS AND BOARD OF DIRECTORS 6 SPONSORS AND DONORS 7 FUTURE OF THE CBAA 8 SPECIAL EVENTS 9 WORKSHOPS 11 TOURS 12 MEETING FINDER, LISTED ALPHABETICALLY 18 MEETING FINDER, LISTED BY DATE AND TIME 22 PROGRAM SCHEDULE 38 CBAA COMMITTEE MEETINGS 39 GENERAL INFORMATION AND MAPS COLLEGE BOOK ART ASSOCIATION MISSION Founded in 2008, The College Book Art Association supports and promotes academic book arts education by fostering the development of its practice, teaching, scholarship and criticism. The College Book Art Association is a non-profit organization fundamentally committed to the teaching of book arts at the college and university level, while supporting such education at all levels, concerned with both the practice and the analysis of the medium. It welcomes as members everyone involved in such teaching and all others who have similar goals and interests. The association aims to engage in a continuing reappraisal of the nature and meaning of the teaching of book arts. The association shall from time to time engage in other charitable activities as determined by the Board of Directors to be appropriate. Membership in the association shall be extended to all persons interested in book arts education or in the furtherance of these arts. For purposes of this constitution, the geographical area covered by the organization shall include, but is not limited to all residents of North America. PRESIDENT’S WELCOME CONFERENCE CHAIR WELCOME John Risseeuw, President 2008-2011 Tony White, Conference Chair Welcome to the College Book Art Association’s 2nd biannual conference. -

Still Not a British Subject: Race and UK Poetry

Editorial How to Cite: Parmar, S. 2020. Still Not a British Subject: Race and UK Poetry. Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry, 12(1): 33, pp. 1–44. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.16995/bip.3384 Published: 09 October 2020 Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and repro- duction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. The Open Library of Humanities is an open access non-profit publisher of scholarly articles and monographs. Sandeep Parmar, ‘Still Not a British Subject: Race and UK Poetry.’ (2020) 12(1): 33 Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry. DOI: https://doi. org/10.16995/bip.3384 EDITORIAL Still Not a British Subject: Race and UK Poetry Sandeep Parmar University of Liverpool, UK [email protected] This article aims to create a set of critical and theoretical frameworks for reading race and contemporary UK poetry. By mapping histories of ‘innova- tive’ poetry from the twentieth century onwards against aesthetic and political questions of form, content and subjectivity, I argue that race and the racialised subject in poetry are informed by market forces as well as longstanding assumptions about authenticity and otherness. -

Word Is Seeking Poetry, Prose, Poetics, Criticism, Reviews, and Visuals for Upcoming Issues

Word For/ Word is seeking poetry, prose, poetics, criticism, reviews, and visuals for upcoming issues. We read submissions year-round. Issue #30 is scheduled for September 2017. Please direct queries and submissions to: Word For/ Word c/o Jonathan Minton 546 Center Avenue Weston, WV 26452 Submissions should be a reasonable length (i.e., 3 to 6 poems, or prose between 50 and 2000 words) and include a biographical note and publication history (or at least a friendly introduction), plus an SASE with appropriate postage for a reply. A brief statement regarding the process, praxis or parole of the submitted work is encouraged, but not required. Please allow one to three months for a response. We will consider simultaneous submissions, but please let us know if any portion of it is accepted elsewhere. We do not consider previously published work. Email queries and submissions may be sent to: [email protected]. Email submissions should be attached as a single .doc, .rtf, .pdf or .txt file. Visuals should be attached individually as .jpg, .png, .gif, or .bmp files. Please include the word "submission" in the subject line of your email. Word For/ Word acquires exclusive first-time printing rights (online or otherwise) for all published works, which are also archived online and may be featured in special print editions of Word For/Word. All rights revert to the authors after publication in Word For/ Word; however, we ask that we be acknowledged if the work is republished elsewhere. Word For/ Word is open to all types of poetry, prose and visual art, but prefers innovative and post-avant work with an astute awareness of the materials, rhythms, trajectories and emerging forms of the contemporary. -

Prospectus 19/ 20 Trinity Laban Conservatoire Of

PROSPECTUS 19/20 TRINITY LABAN CONSERVATOIRE OF MUSIC & DANCE CONTENTS 3 Principal’s Welcome 56 Music 4 Why You Should #ChooseTL 58 Performance Opportunities 6 How to #ExperienceTL 60 Music Programmes FORWARD 8 Our Home in London 60 Undergraduate Programmes 10 Student Life 62 Postgraduate Programmes 64 Professional Development Programmes 12 Accommodation 13 Students' Union 66 Academic Studies 14 Student Services 70 Music Departments 16 International Community 70 Music Education THINKING 18 Global Links 72 Composition 74 Jazz Trinity Laban is a unique partnership 20 Professional Partnerships 76 Keyboard in music and dance that is redefining 22 CoLab 78 Strings the conservatoire of the 21st century. 24 Research 80 Vocal Studies 82 Wind, Brass & Percussion Our mission: to advance the art forms 28 Dance 86 Careers in Music of music and dance by bringing together 30 Dance Staff 88 Music Alumni artists to train, collaborate, research WELCOME 32 Performance Environment and perform in an environment of 98 Musical Theatre 34 Transitions Dance Company creative and technical excellence. 36 Dance Programmes 106 How to Apply 36 Undergraduate Programmes 108 Auditions 40 Masters Programmes 44 Diploma Programmes 110 Fees, Funding & Scholarships 46 Careers in Dance 111 Admissions FAQs 48 Dance Alumni 114 How to Find Us Trinity Laban, the UK’s first conservatoire of music and dance, was formed in 2005 by the coming together of Trinity College of Music and Laban, two leading centres of music and dance. Building on our distinctive heritage – and our extensive experience in providing innovative education and training in the performing arts – we embrace the new, the experimental and the unexpected. -

Noumenon 41 Outside the Theatre

EDITORIAL “Yes, Brian Thurogood from Waiheke here. You were going to send out that information two weeks ago.” Noumenon is published 10 times per year, hopefully "Yes, Brian. I'm sorry but we've had a terrible at 5-weekly intervals. week. In fact, a terrible fortnight — the worst I've Subscriptions are: ever had. I think. Although the air strike has been . S5.7S/10 issu es NZ [incl. postage] over for two weeks we're still drastically affected S12.25/10 issues | Surface ] S7.00/I0 issues by ” "Oh. I'm sorry to hear that.” S13.25/10 issues Britain [Airmail] . "Well, we've had to borrow equipment hack, . S7.00/I0 issues [Surface] . even go to other suppliers — honestly, it's been Retail |New Zealand] 7 5c/copy diabolical.” Trade Discount . Less ‘6 "In a way it's good to hear we're not the only ones with weeks like that.” Noum mon Is edited end published by: "No, you're not — not by a long shot.” Brian Thurogood “Okay, we'll hear from you soon.” 40 Korora Road, Oneroa "Yes, I'll finish it tonight, or at the latest, to Waiheke Island, HaurakiGulf morrow morning.” NEW ZEALAND Phone WH 8502 Art Consultant: Colin Wlbon Hello again. But let me tell you the good news. Typesetting & Assistance: Kath Alber Next issue, gods and demons willing, will see the Subscription cheques, postal notes or Bank drafts should be introduction of the marvelous made payable to Noumenon and sent to the above address. High Tech, Silicon Chip, Laser Generated We welcome unsolicited contributions. -

Pure Psychic Chance Radio: 2016 Jim Leftwich

Pure Psychic Chance Radio: 2016 Jim Leftwich Table of Contents Pure Psychic Chance Radio: Essays 2016 1. Permission slips: Thinking and breathing among John Crouse's UNFORBIDDENS 2. ACTs (improvised moderate militiamen: "Makeshift merger provost!") 3. Applied Experimental Sdvigology / Theoretical and Historical Sdvigology 4. HOW DO YOU THINK IT FEELS: On The Memorial Edition of Frank O’Hara’s In Memory of My Feelings 5. mirror lungeyser: On Cy Twombly, Poems to the Sea XIX 6. My Own Crude Rituals 7. A Preliminary Historiography of an Imagined Ongoing: 1830, 1896, 1962, 2028... 8. In The Recombinative Syntax Zone. Two Bennett poems partially erased by Lucien Suel. In the Recombinative Grammar Zone. 9. Three In The Morning: Reading 2 Poems By Bay Kelley from LAFT 35 10. The Glue Is On The Sausage: Reading A Poem by Crag Hill in LAFT 32 11. My Wrong Notes: On Joe Maneri, Microtones, Asemic Writing, The Iskra, and The Unnecessary Neurosis of Influence 12. Noisic Elements: Micro-tours, The Stool Sample Ensemble, Speaking Zaum To Power 13. TOTAL ASSAULT ON THE CULTURE: The Fuck You APO-33, Fantasy Politics, Mis-hearing the MC5... 14. DIRTY VISPO: Da Vinci To Pollock To d.a.levy 15. WHERE DO THEY LEARN THIS STUFF? An email exchange with John Crouse 16. FURTHER SUBVERSION SEEMS IN ORDER: Reading Poems by Basinski, Ackerman and Surllama in LAFT 33 17. A Collage by Tom Cassidy, Sent With The MinneDaDa 1984 Mail Art Show Doc, Postmarked Minneapolis MN 07 Sep '16 18. DIRTY VISPO II (Henri Michaux, Christian Dotremont, derek beaulieu, Scott MacLeod, Joel Lipman on d.a.levy, Lori Emerson on the history of the term "dirty concrete poetry", Albert Ayler, Jungian mandalas) 19. -

The Compositional Language of Kenny Wheeler

THE COMPOSITIONAL LANGUAGE OF KENNY WHEELER by Paul Rushka Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montreal March 2014 A paper submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of D.Mus. Performance Studies ©Paul Rushka 2014 2 ABSTRACT The roots of jazz composition are found in the canon ofthe Great American Songbook, which constitutes the majority of standard jazz repertoire and set the compositional models for jazz. Beginning in the 1960s, leading composers including Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock began stretching the boundaries set by this standard repertoire, with the goal of introducing new compositional elements in order to expand that model. Trumpeter, composer, and arranger Kenny Wheeler has been at the forefront of European jazz music since the late 1960s and his works exemplify a contemporary approach to jazz composition. This paper investigates six pieces from Wheeler's songbook and identifies the compositional elements of his language and how he has developed an original voice through the use and adaptation of these elements. In order to identify these traits, I analyzed the melodic, harmonic, structural and textural aspects of these works by studying both the scores and recordings. Each of the pieces I analyzed demonstrates qualities consistent with Wheeler's compositional style, such as the expansion oftonality through the use of mode mixture, non-functional harmonic progressions, melodic composition through intervallic sequence, use of metric changes within a song form, and structural variation. Finally, the demands of Wheeler's music on the performer are examined. 3 Resume La composition jazz est enracinee dans le Grand repertoire American de la chanson, ou "Great American Songbook", qui constitue la plus grande partie du repertoire standard de jazz, et en a defini les principes compositionnels. -

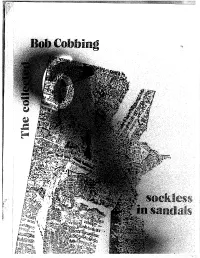

Sockless in Sandals: Collected Poems of Bob Cobbing, Vol 6

SOC KLESS .1. N SAN D A LS COLLECTED POEMS VOLUME SIX BY BOB COBBING SECOND AEON PUB L .1 C A·T JON S 1 985 SOCKLESS IN SANDALS Collected Poems Volume Six by DOD CODDING ISDN 0 901068 59 4 Published by Second Aeon Publications 19 Southminster Road, Penylan, Cardiff Second Aeon is a member of ALP CONTE NT S 5 Introduction by Peter Finch 7 A guide to the "new" 8 If he knew what he was doing, he would do it better: 9 Police left holding bag I In Taiwan 10 Fifteen months ago, Gil Singh I This is my first poem 11 The logic is simple I Scientific research has shown ~.... " 12 Expert systems - a basis of "knowledge 13 Special Offer 14 What's in a name - Thatcher 15 Katalin Ladik 16 Edwin Morgan 17 The Jack poem 18 The Tom poems 22 Poetical anawithems, wordslishing 23 Bo?angles 24 A-nan an' nan 27 STAY - Lem / PEH - pa - hahl 28 tem - UHQ 29 tem - kway - eh - les 30 The Sacred Mushroom 32 Umbo, tubule 33 Alphabet of Californian Fishes 34 Angels Camp, Berkeley 35 Allosaurus, Amebelodon 36 Acrilan, Adidas 37 A~bry, ambree 38 Po~ybasite - Monoclinic 39 Rainbow 40 Whale 41 SOL 42 SUN 43 A Classification of Danish Riddles with Unexpected Solutions 44 Lion, Lenin, Leonora, Lamb 45 See Water 46 Alevin, Bars, Causapscal -47 U" Me Transfer 48 A bean-feast that bore fruit 50 ANT WAR WON 51 Van Gogh - The Annotated Paintings 59 Notes by Bob Cobbing (Cover by Peter Finch) - T; SOCKLESS IN SANDALS It seems appropriate that Second Aeon which hasn't produced so much as a broadsheet for a decade should move into print again with a volume by Bob Cobbing, its lon~ term supporter and mentor. -

Zzcalifornia Aconservatory

a conservatory california zz EDITION 14.0 2014 – 2015 general catalog California Jazz Conservatory Academic Calendar 2014 – 2015* Spring Semester 2014 Auditions for Spring 2014 By Appointment Academic and Administrative Holiday Jan 20 First Day of Spring Instruction Jan 21 Last Day to Add / Drop a Class Jan 31 Academic and Administrative Holiday Feb 17 Spring Recess March 24 – March 30 Auditions for Fall 2014 By Appointment Last Day of Instruction May 11 Final Examinations and Juries May 12 – 16 Commencement May 17 Fall 2014 Enrollment Deposit Due On or before June 1 Fall 2014 Registration On or before August 4 Fall Semester 2014 Auditions for Fall 2014 By Appointment New Student Orientation Aug 14 First Day of Fall Instruction Aug 18 Academic and Administrative Holiday Sept 1 Last Day to Add/Drop a Class Sept 2 Academic and Administrative Holiday Nov 24 – Nov 30 CJC academic calendar Spring 2015 Enrollment Deposit Due On or before Dec 1 Spring 2015 Registration Jan 5 – 9 Last Day of Instruction Dec 7 Final Examinations and Juries Dec 8 – 14 Commencement Dec 20 Winter Recess Dec 15 – Jan 19 Spring Semester 2015 Auditions for Spring 2015 By Appointment Academic and Administrative Holiday Jan 19 First Day of Spring Instruction Jan 20 Last Day to Add / Drop a Class Feb 3 Academic and Administrative Holiday Feb 16 Spring Recess March 23 – March 29 Auditions for Fall 2015 By Appointment Last Day of Instruction May 10 Final Examinations and Juries May 11 – 15 Commencement May 16 A Z Z C J O N A S Fall 2015 Enrollment Deposit Due On or before June 1 I E Fall 2015 Registration August 3 – 7 N R R V O A D F S T E E I V * Please note: Edition 14 of the CJC 2014–2015 General Catalog C O L E N L R O E A I covers the time period of July 15, 2014 – July 14, 2015. -

Download Publication

Arts Council OF GREAT BRITAI N Patronage and Responsibility Thirty=fourth annual report and accounts 1978/79 ARTS COUNCIL OF GREAT BRITAIN REFERENCE ONLY DO NOT REMOVE fROwI THE LIBRARY Thirty-fourth Annual Report and Accounts 1979 ISSN 0066-813 3 Published by the Arts Council of Great Britai n 105 Piccadilly, London W 1V OAU Designed by Duncan Firt h Printed by Watmoughs Limited, Idle, Bradford ; and London Cover pictures : Dave Atkins (the Foreman) and Liz Robertson (Eliza) in the Leicester Haymarket production ofMy Fair Lady, produced by Cameron Mackintosh with special funds from Arts Council Touring (photo : Donald Cooper), and Ian McKellen (Prozorov) and Susan Trac y (Natalya) in the Royal Shakespeare Company's small- scale tour of The Three Sisters . Contents 4 Chairman's Introductio n 5 Secretary-General's Report 12 Regional Developmen t 13 Drama 16 Music and Dance 20 Visual Arts 24 Literature 25 Touring 27 Festivals 27 Arts Centres 28 Community Art s 29 Performance Art 29 Ethnic Arts 30 Marketing 30 Housing the Arts 31 Training 31 Education 32 Research and Informatio n 33 Press Office 33 Publications 34 Scotland 36 Wales 38 Membership of Council and Staff 39 Council, Committees and Panels 47 Annual Accounts , Awards, Funds and Exhibitions The objects for which the Arts Council of Great Britain is established by Royal Charter are : 1 To develop and improve the knowledge , understanding and practice of the arts ; 2 To increase the accessibility of the arts to the public throughout Great Britain ; and 3 To co-operate with government departments, local authorities and other bodies to achieve these objects . -

Radio 3 Listings for 12 – 18 January 2019 Page

Radio 3 Listings for 12 – 18 January 2019 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 12 JANUARY 2019 Rudolf Macudzinski (piano), Bratislava Slovak Radio Martin Handley presents Radio 3's classical breakfast show, Symphony Orchestra, Ludovít Rajter (conductor) featuring listener requests. SAT 01:00 Through the Night (m0001yjc) The Art of the Cello 04:03 AM Email [email protected] Orlande de Lassus (1532-1594) Estelle Revaz in a solo recital featuring Bach, Berio and Dulces Exuviae - motet Gubaidulina recorded in Switzerland. Jonathan Swain presents. Currende, Erik van Nevel (conductor) SAT 09:00 Record Review (m0001zpc) with Andrew McGregor. 01:01 AM 04:09 AM Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Ludwig Norman (1831-1885), Niklas Willén (arranger) 9.00am Prelude from Cello Suite No 3 in C BWV1009 Andante Sostenuto for orchestra Estelle Revaz (cello) Sveriges Radios Symfoniorkester [Swedish Radio Symphony ‘L’Alessandro amante’ – 18th century songs and instrumental Orchestra], Niklas Willén (conductor) pieces by Bononcini, Handel, Pescetti, Steffani, Draghi, 01:04 AM Mancini, Vinci, Leo & Porpora Luciano Berio (1925-2003) 04:19 AM Xavier Sabata (counter tenor) Les mots sont allés Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) Vespres D’arnadi (ensemble) Estelle Revaz (cello) Mónár Anna (Anie Miller) from Hungarian Folk Music Dani Espasa (director & harpsichord) Polina Pasztircsák (soprano), Zóltan Kocsis (piano) Aparte AP192 01:07 AM http://www.apartemusic.com/discography/lalessandra-amante/ Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) 04:27 AM Allemande from Cello Suite No 3 in C, BWV 1009