Willa Cather REVIEW Volume 60 Z No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Willa Cather's Spirit Lives

Willa Cather’s Spirit Lives On! October 19-20, 2018 A National Celebration of Willa Cather in Jaffrey, NH & the 100th Anniversary of My Ántonia Willa Cather, writing at the Shattuck Inn at the foot of Mt. Monadnock (left: photo taken by Edith Lewis), and standing by the tent where she wrote My Mt. Monadnock’s 3,165’ peak (above the Horsesheds in this photo of the 1775 Jaffrey Meeting- Antonia (right) house) has attracted writers and artists to Jaffrey for nearly two centuries. Come celebrate Cather in words, music, theater and food in the places and autumn mountain air she loved! First Church Melville Academy Museum Edith Lewis Jaffrey Civic Center Willa Cather’s gravestone Tickets are $75 * RESERVE EARLY * Only 140 tickets! Details at jaffreychamber.com Agenda: Friday evening, Oct. 19: Welcome Reception. The Cather My Ántonia Celebration will start in the red brick Jaffrey Civic Center. Saturday, Oct. 20: Saturday events will begin at the Meetinghouse followed by guided visits to three Ashley Olson Cather sites where young Project Shakespeare actors will enact passages from My Ántonia. • Tour sites will include the grave where Willa was buried in 1947 and where Edith Lewis was buried 25 years later; the Melville Academy Museum display on Willa and Edith; and the field where Willa wrote My Ántonia in a tent and also wrote One of Ours. • Following the tours, guests will enjoy a boxed lunch provided by the Shattuck Golf Club Grill. • After lunch, Ashley Olson and Tracy Tucker, directors of the Willa Cather Foundation, will give a presentation on My Ántonia at the 1775 Jaffrey Meetinghouse. -

Lawyers in Willa Cather's Fiction, Nebraska Lawyer

Lawyers in Willa Cather’s Fiction: The Good, The Bad and The Really Ugly by Laurie Smith Camp Cather Homestead near Red Cloud NE uch of the world knows Nebraska through the literature of If Nebraska’s preeminent lawyer and legal scholar fared so poorly in Willa Cather.1 Because her characters were often based on Cather’s estimation, what did she think of other members of the bar? Mthe Nebraskans she encountered in her early years,2 her books and stories invite us to see ourselves as others see us— The Good: whether we like it or not. In “A Lost Lady,”4 Judge Pommeroy was a modest and conscientious Roscoe Pound didn’t like it one bit when Cather excoriated him as a lawyer in the mythical town of Sweetwater, Nebraska. Pommeroy pompous bully in an 1894 ”character study” published by the advised his client, Captain Daniel Forrester,5 during Forrester’s University of Nebraska. She said: “He loves to take rather weak- prosperous years, and helped him to meet all his legal and moral minded persons and browbeat them, argue them down, Latin them obligations when the depression of the 1890's closed banks and col- into a corner, and botany them into a shapeless mass.”3 lapsed investments. Pommeroy appealed to the integrity of his clients, guided them by example, and encouraged them to respect Laurie Smith Camp has served as the rights of others. He agonized about the decline of ethical stan- Nebraska’s deputy attorney general dards in the Nebraska legal profession, and advised his own nephew for criminal matters since 1995. -

Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004)

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Department of Professional Studies Studies 2004 Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De- Mythologizing of the American West Jennie A. Harrop George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac Recommended Citation Harrop, Jennie A., "Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004). Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies. Paper 5. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Professional Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGLING FOR REPOSE: WALLACE STEGNER AND THE DE-MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Jennie A. Camp June 2004 Advisor: Dr. Margaret Earley Whitt Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ©Copyright by Jennie A. Camp 2004 All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. GRADUATE STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF DENVER Upon the recommendation of the chairperson of the Department of English this dissertation is hereby accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Profess^inJ charge of dissertation Vice Provost for Graduate Studies / if H Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

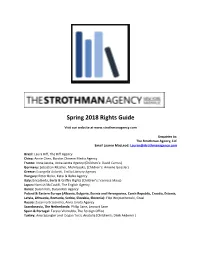

Spring 2018 Rights Guide

Spring 2018 Rights Guide Visit our website at www.strothmanagency.com Enquiries to: The Strothman Agency, LLC Email Lauren MacLeod: [email protected] Brazil: Laura Riff, The Riff Agency China: Annie Chen, Bardon Chinese Media Agency France: Anna Jarota, Anna Jarota Agency (Children’s: David Camus) Germany: Sebastian Ritscher, Mohrbooks, (Children’s: Annelie Geissler) Greece: Evangelia Avloniti, Ersilia Literary Agency Hungary: Peter Bolza, Katai & Bolza Agency Italy: Erica Berla, Berla & Griffini Rights (Children’s: Vanessa Maus) Japan: Hamish McCaskill, The English Agency Korea: Duran Kim, Duran Kim Agency Poland & Eastern Europe (Albania, Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Czech Republic, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia): Filip Wojciechowski, Graal Russia: Zuzanna Brzezinska, Anna Jarota Agency Scandanavia, The Netherlands: Philip Sane, Lennart Sane Spain & Portugal: Teresa Vilarrubla, The Foreign Office Turkey: Amy Spangler and Dogan Terzi, Anatolia (Children's: Dilek Akdemir ) Early Warning: Upcoming & Recently Sold Ruth Ben-Ghiat: Strongmen: How They Rise, Why They Succeed, When They Fall ……………………3 Kathryn Miles: Killers on the Trail: Love, Murder, and the Quest for Justice in America's Wild Places ………………………….……………………………………………………………………..……..…………………………..…4 Michelle Wilde Anderson: Left for Dead: Local Government in the Post-Industrial Age ……..………5 Richard Ford: Dress Codes: Laws of Attire and Crime of Fashion ………………………….……………………6 Now Available: Adult Titles David Kertzer: The Pope Who -

SSAWW-2021-Conference-Program-11-July-2021.Docx

2021 SSAWW Conference Schedule (Draft 11 July 2021) WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 3 Conference Registration: 4:00-8:00 p.m., Regency THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 4 Registration: 6:30 a.m.-4:00 p.m., Regency Book exhibition: 8:15 a.m.-5:00 p.m., Brightons Mentoring Breakfast: 7:00 a.m.-8:15 a.m., Hamptons Thursday, 8:30-9:45 a.m. Session 1A, North Whitehall “Gothic Ecologies: Alcott, Her Contexts, and Contemporaries” Sponsored by the Louisa May Alcott Society Chair: Sandra Harbert Petrulionis, Pennsylvania State University, Altoona ● "Never Mind the Boys": Gothic Persuasions of Jane Goodwin Austin and Louisa May Alcott Kari Miller, Perimeter College at Georgia State University ● Wealth, Handicaps, and Jewels: Alcott's Gothic Tales of Dis-Possession Monika Elbert, Montclair State University ● Alcott in the Cadre of Scribbling Women: 'Realizing' the Female Gothic for Nineteenth Century American Periodicals Wendy Fall, Marquette University Session 1B, Guilford “Pedagogy and the Archives (Part I)” Chair: TBD ● Commonplace Book Practices and the Digital Archive Kirsten Paine, University of Pittsburgh ● Making Literary Artifacts and Exhibits as Acts of Scholarship Mollie Barnes, University of South Carolina Beaufort ● "My dearest sweet Anna": Transcribing Laura Curtis Bullard's Love Letters to Anna Dickinson and Zooming to the Library of Congress Denise Kohn, Baldwin Wallace University ● Nineteenth Century Science of Surgery as Cure for the Greatest Curse Sigrid Schönfelder, Universität Passau 1 - DRAFT: 11 July 2021 Session 1C, Westminster (Need AV) “Recovering Abolitionist Lives and Histories” Chair: Laura L. Mielke, University of Kansas ● Audubon's Black Sisters Brigitte Fielder, University of Wisconsin-Madison ● Recovery Work and the Case of Fanny Kemble's Journal of a Residence on a Georgia Plantation, 1838-39 Laura L. -

REVIEW Volume 60 Z No

REVIEW Volume 60 z No. 3 Winter 2018 My Ántonia at 100 Willa Cather REVIEW Volume 60 z No. 3 | Winter 2018 28 35 2 15 22 CONTENTS 1 Letters from the Executive Director, the President 20 Reading My Ántonia Gave My Life a New Roadmap and the Editor Nancy Selvaggio Picchi 2 Sharing Ántonia: A Granddaughter’s Purpose 22 My Grandmother—My Ántonia z Kent Pavelka Tracy Sanford Tucker z Daryl W. Palmer 23 Growing Up with My Ántonia z Fritz Mountford 10 Nebraska, France, Bohemia: “What a Little Circle Man’s My Ántonia, My Grandparents, and Me z Ashley Nolan Olson Experience Is” z Stéphanie Durrans 24 24 Reflection onMy Ántonia z Ann M. Ryan 10 Walking into My Ántonia . z Betty Kort 25 Red Cloud, Then and Now z Amy Springer 11 Talking Ántonia z Marilee Lindemann 26 Libby Larsen’s My Ántonia (2000) z Jane Dressler 12 Farms and Wilderness . and Family z Aisling McDermott 27 How I Met Willa Cather and Her My Ántonia z Petr Just 13 Cather in the Classroom z William Anderson 28 An Immigrant on Immigrants z Richard Norton Smith 14 Each Time, Something New to Love z Trish Schreiber 29 My Two Ántonias z Evelyn Funda 14 Our Reflections onMy Ántonia: A Family Perspective John Cather Ickis z Margaret Ickis Fernbacher 30 Pioneer Days in Webster County z Priscilla Hollingshead 15 Looking Back at My Ántonia z Sharon O’Brien 31 Growing Up in the World of Willa Cather z Kay Hunter Stahly 16 My Ántonia and the Power of Place z Jarrod McCartney 32 “Selah” z Kirsten Frazelle 17 My Ántonia, the Scholarly Edition, and Me z Kari A. -

Troll Garden and Selected Stories

Troll Garden and Selected Stories Willa Cather The Project Gutenberg Etext of The Troll Garden and Selected Stories, by Willa Cather. Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. The Troll Garden and Selected Stories by Willa Cather. October, 1995 [Etext #346] The Project Gutenberg Etext of The Troll Garden and Selected Stories, by Willa Cather. *****This file should be named troll10.txt or troll10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, troll11.txt. VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, troll10a.txt. This etext was created by Judith Boss, Omaha, Nebraska. The equipment: an IBM-compatible 486/50, a Hewlett-Packard ScanJet IIc flatbed scanner, and Calera Recognition Systems' M/600 Series Professional OCR software and RISC accelerator board donated by Calera Recognition Systems. We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, for time for better editing. Please note: neither this list nor its contents are final till midnight of the last day of the month of any such announcement. -

O Pioneers!" and Mourning Dove's "Cogewea, the Half-Blood"

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2006 Unsettling nature at the frontier| Nature, narrative, and female empowerment in Willa Cather's "O Pioneers!" and Mourning Dove's "Cogewea, the Half-Blood" Erin E. Hendel The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hendel, Erin E., "Unsettling nature at the frontier| Nature, narrative, and female empowerment in Willa Cather's "O Pioneers!" and Mourning Dove's "Cogewea, the Half-Blood"" (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3973. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3973 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature Yes, I grant permission ^ No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature: Date j Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 UNSETTLING NATURE AT THE FRONTIER: NATURE, NARRATIVE, AND FEMALE EMPOWERMENT IN WILLA CATHER'S O PIONEERS! AND MOURNING DOVE'S COGEWEA, THE HALF-BLOOD "Jhv Erin E. -

An Association Copy of Note: Willa Cather's Copy of Aucassin & Nicolete

An Association Copy of Note: Willa Cather’s copy of Aucassin & Nicolete From 1896 to 1906 the renown American writer and novelist, Willa Cather, resided in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Twelve novels with now more or less familiar titles like O Pioneers! (1913), The Song of the Lark (1915), and Death comes for the Archbishop (1927) thrilled American readers. Long before her novels, however, there were more modest achievements such as her first and only book of poetry, April Twilights (1903), her first collection of short story fiction, The Troll Garden (1905) and her work as editor of Home Monthly, the magazine which brought her to Pittsburgh in the first place. In 1898 she began work at the Pittsburgh Daily Leader but then in 1901 she took a job teaching high school students in Pittsburgh. Teaching would not become her mainstay and by 1906 she was ready to move on to a job at McClure’s Magazine in New York City which eventually would lead to her becoming its managing editor. McClure’s was one of America’s most successful and popular literary magazines, and it was while in New York that Cather would meet her lifelong companion, Edith Lewis. But wait, we’re getting a bit ahead of ourselves. It’s those Pittsburgh years that are of the most direct concern for this brief essay. Willa Cather often referred to Pittsburgh as the “birthplace” of her writing career, and the very reason why the essay exists at all is because of a little book found from those natal literary years. We have to go back to September 18, 2012 when I came across the notice from an upper Mid-Western book dealer advertised a little Mosher book which he said was from Willa Cather’s library: Aucassin & Nicolete. -

The Unmentioned Affairs in Willa Cather's O Pioneers!

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 7-18-2008 Illuminating the Queer Subtext: the Unmentioned Affairs in Willa Cather's O Pioneers! Nora Neill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Neill, Nora, "Illuminating the Queer Subtext: the Unmentioned Affairs in Willa Cather's O Pioneers!." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/41 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ILLUMINATING THE QUEER SUBTEXT: THE UNMENTIONED AFFAIRS IN WILLA CATHER’S O PIONEERS! by NORA NEILL Under Direction of Dr. Audrey Goodman ABSTRACT Willa Cather contests the contemporary notion that identification links to a natural or original order. For example, that man equals masculine and femininity comes from an essential connection to woman. Cather deconstructs normativity through her use of character relationships in order to redefine successful interpersonal alliances. Thus, Alexandra, the protagonist of O Pioneers! builds a home and friendships that exemplify alternatives to stasis. My readings of O Pioneers! display the places in the novel where Cather subtly contests the ideology of naturalization. I make lesbian erotic and queer social interactions visible through a discourse on Cather’s symbolism. I favor queer theory as a mode of inquiry that magnifies the power and presence of heteronormativity and I examine Cather’s work as a critique of cultural principles that inflict violence against individuals who participate in dissent from conformity. -

Newsletter & Review

NEWSLETTER & REVIEW Volume 56, No. 2 Spring 2013 For really bad weather I wear knickerbockers Then really I like the work, grind though it is In addition to painting the bathroom and doing the house work and trying to write a novel, I have been becoming rather “famous” lately Mr. McClure tells me that he does not think I will ever be able to do much at writing stories As for me, I have cared too much, about people and places I have some white canvas shoes with red rubber soles that I got in Boston, and they are fine for rock climbing When I am old and can’t run about the desert anymore, it will always be here in this book for me Is it possible that it took one man thirty working days to make my corrections? I think daughters understand and love their mothers so much more as they grow older themselves The novel will have to be called “Claude” I tried to get over all that by a long apprenticeship to Henry James and Mrs. Wharton She is the embodiment of all my feelings about those early emigrants in the prairie country Requests like yours take a great deal of my time Everything you packed carried wonderfully— not a wrinkle Deal in this case as Father would have done I used to watch out of the front windows, hoping to see Mrs. Anderson coming down the road And then was the time when things were very hard at home in Red Cloud My nieces have outlived those things, but I will never outlive them Willa Cather NEWSLETTER & REVIEW Volume 56, No. -

A Brief History of Beacon Press

Dear Reader, In 2004, Beacon Press will complete 150 years of continuous book pub- lishing. This rare achievement in American publishing is a milestone a mere handful of active houses can claim. To mark this important anniversary, Beacon retained author Susan Wilson to research the history of the press in archives and through extensive interviews. What you see printed here is only a précis of her work, though we hope it will give you a sense of the importance of the press over the past three centuries. Ms. Wilson’s interviews with key fig- ures in the press over the past sixty years are preserved on high-quality digital minidisks; many have been transcribed as well. Her notes from the extensive Beacon archives held at Harvard Andover Library, which includes a fuller annotated bibliography of books published by the press, are also preserved for scholars and interested readers. Both will be available through the Beacon website (www.beacon.org) in the com- ing months. Over the years, many notable Americans, from George Emerson to Albert Einstein to Juliet Schor, have recognized the importance and vitality of this press. I hope and believe that the next 150 years will be even more rewarding ones for the press. Helene Atwan Director 1902 1904 1929 1933 1947 1950 1959 1966 1967 1970 1986 1992 A BRIEF HISTORY OF BEACON PRESS Beacon Press gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Unitarian Universalist Funding Program, which has made this project possible. part 1 the early years: 1854–1900 The history of Beacon Press actually begins in 1825, the year the American Unitarian Association (AUA) was formed.