Tennessee's Educator Preparation Report Card: Progress Over Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAMPUS SITUATION Rmr M P L a N G R O U P the Nashville Connection

CAMPUS SITUATION rmr m p l a n g r o u p The Nashville Connection. Belmont University is situated near Nashville’s midtown, within close proximity to the city’s cultural, academic, residential and commercial centers. While the university itself offers students a wide array of m outstanding learning and living resources, the campus’ convenient location extends opportunities for students to interact with a dynamic community and access additional quality resources and services. On the north edge of campus, the historic Belmont Mansion sits atop a hill overlooking the bustling traffic of Wedgewood Avenue, a major gateway to other Nashville activity centers. This avenue provides convenient access to: • Vanderbilt University , a respected private university with an enrollment of nearly 11,000 undergraduate and graduate students; • Vanderbilt Medical Center , a national leader in medical education, research, and patient care; • Music Row , the heart of the country music industry – a midtown collection of major recording label offices and recording studios, including Belmont’s own Ocean Way studios; • Historic residential districts , featuring an array of single- and multi-family homes in safe, friendly neighborhoods; • Hillsboro Village and the 21 st Avenue corridor , a vibrant retail, dining and entertainment district; and • Interstate 65 , a major pathway around, in and out of Nashville. Belmont Boulevard, which forms the west side of campus, also serves another important arterial function, connecting Belmont University to David Lipscomb University, a Christian faith-based liberal arts institution. Between these two growing institutions, students will find commercial resources, personal service providers and multi-family housing, all surrounded by revitalized residential neighborhoods and pedestrian and bicycle pathways. -

2018/2020 Undergraduate Bulletin

FISK 2018/2020 Undergraduate Bulletin 1 Cover image: Cravath Hall, named for Fisk’s first president (1875-1900) photo: photographer unknown 2 About the Bulletin Inquiries concerning normal operations of the The content of this Bulletin represents the most current institution such as admission requirements, financial aid, information available at the time of publication. As Fisk educational programs, etc., should be addressed directly to University continues to provide the highest quality of the appropriate office at Fisk University. The Commission intellectual and leadership development opportunities, the on Colleges is to be contacted only if there is evidence that curriculum is always expanding to meet the changes in appears to support an institution’s significant non- graduate and professional training as well as the changing compliance with a requirement or standard. demands of the global workforce. New opportunities will Even before regional accreditation was available to arise and, subsequently, modifications may be made to African-American institutions, Fisk had gained recognition existing programs and to the information contained in this by leading universities throughout the nation and by such Bulletin without prior notice. Thus, while the provisions of agencies as the Board of Regents of the State of New this Bulletin will be applied as stated, Fisk University York, thereby enabling Fisk graduates' acceptance into retains the right to change the policies and programs graduate and professional schools. In 1930, Fisk became contained herein at its discretion. The Bulletin is not an the first African-American institution to gain accreditation irrevocable contract between Fisk University and a student. by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. -

RN/Prof Annual Report

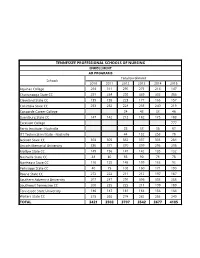

TENNESSEE PROFESSIONAL SCHOOLS OF NURSING ENROLLMENT AD PROGRAMS Total Enrollment Schools 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Aquinas College 294 311 296 271 214 147 Chattanooga State CC 291 334 292 339 302 366 Cleveland State CC 139 155 223 177 166 157 Columbia State CC 253 252 228 235 240 219 Concorde Career College 24 43 38 46 Dyersburg State CC 147 142 212 182 175 183 Excelsior College 777 Fortis Institute - Nashville 25 33 35 67 ITT Technical Institute - Nashville 44 132 253 78 Jackson State CC 368 305 332 307 303 284 Lincoln Memorial University 336 371 370 399 296 295 Motlow State CC 149 156 147 142 135 132 Nashville State CC 48 80 85 90 78 75 Northeast State CC 116 125 145 109 163 93 Pellissippi State CC 40 75 102 160 171 190 Roane State CC 272 222 211 212 197 187 Southern Adventist University 267 287 291 306 303 288 Southwest Tennessee CC 200 235 225 211 199 189 Tennessee State University 186 187 181 183 156 163 Walters State CC 315 266 274 282 253 249 TOTAL 3421 3503 3707 3542 3677 4185 TENNESSEE PROFESSIONAL SCHOOLS OF NURSING ENROLLMENT BSN PROGRAMS Initial RN Total Enrollment Schools RN to BSN Licensure 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 American Sentinel University 43 43 Aquinas College 42 23 57 38 20 19 26 65 Arkansas State University 10 2 10 Austin Peay State University 232 63 251 260 258 290 323 295 Baptist Memorial College of Hlth Sciences 466 38 474 467 495 496 526 504 Belmont University 491 12 521 594 497 552 574 503 Bethel University 39 31 22 38 43 54 75 70 Carson Newman College 113 3 114 111 102 101 111 116 Chamberlain College -

Belmont University Vision 2020 Diversity Committee Report

Belmont University Diversity Committee Report Belmont University Vision 2020 Diversity Committee Report Diversity Committee Co-Chairs: La Kiesha Armstrong, Associate Registrar; Sabrina Sullenberger, Associate Professor of Social Work Senior Leader Contact: Dr. Susan West Committee Members: Sharon Boyce, Funds Accountant, Finance and Accounting Mary Anna Brown, Assistant Director, UMPR Angie Bryant, Assistant Dean of Students, Fitness and Rec, SA Jose Gonzalez, Instructor of Entrepreneurship and Management, COBA Phil Johnston, Dean, College of Pharmacy Chris Millar, Business Manager, CLASS Greg Pillon, Director of Communications, UMPR Sabrina Salvant, Director, Entry Level Doctorate, OT, CHS Cosonya Stephens, Budget Analyst, Finance and Accounting Jeremy Capps, Student, President BSA 1 Belmont University Diversity Committee Report Project Scope and Objectives The Vision 2020 team was formed in early September 2016, and at that time we received our charge with our project scope and objectives from Senior Leadership. Project Scope: Belmont’s Welcome Home initiative and newly created Office of Multicultural Learning and Experience were established by senior leadership to support the university’s goal of becoming increasingly more diverse and broadly reflective of our local and global communities. The Welcome Home team meets regularly to explore initiatives and plan strategies to create a culture of inclusion, to ensure learning experiences that enable students to gain strong intercultural competencies and to actively and intentionally recruit diverse faculty, staff and students. Through the efforts of this group and the Office of Multicultural Learning and Experience, Belmont will strive to become a welcoming environment for all. Project Objectives: • Work closely with the WHT to ascertain their current efforts and needs. -

College of Nursing and Health Sciences

COLLEGE OF NURSING AND HEALTH SCIENCES Dean Kelly Harden (2007). Dean, Professor of Nursing. A.S.N., Mississippi County Community College; B.S.N., Excelsior College; M.S.N., University of Missouri-St. Louis; D.N.Sc., University of Tennessee Health Science Center. LeAnne Wilhite ( ). Associate Dean for Undergraduate Programs and Assistant Professor of Nursing. B.S.N., Union University; M.S.N., University of Tennessee, Memphis; D.N.P., Union University. Mission Statement The mission of the College of Nursing is to be excellence-driven, Christ-centered, people-focused, and future-directed while preparing qualified individuals for a career in the caring, therapeutic, teaching profession of nursing. Degrees Offered Bachelor of Science in Nursing • Traditional BSN • Accelerated BSN • RN to BSN Adult Studies/Bachelor of Science in Nursing • RN to BSN Track • Second Bachelor’s Degree Accelerated Track • First Bachelor’s Degree Accelerated Track 2019-2020 COLLEGE OF NURSING AND HEALTH SCIENCES 176 COLLEGE OF NURSING COLLEGE OF NURSING AND HEALTH SCIENCES Faculty Christina Davis ( ). Assistant Professor. B.S.N. and M.S.N., Union University. Shayla Alexander (2018). Assistant Professor. B.S.N. and M.S.N., Union University. Jennifer Delk ( ). Assistant Professor and Chair of Undergraduate Programs – Jackson. B.S.N. and M.S.N., Cathy Ammerman (2017). Associate Professor. A.S.N., Union University. Western Kentucky University; B.S.N., University of Evansville; M.S.N., Western Kentucky University; D.N.P., Melinda Dunavant ( ). Assistant Professor. B.S.N., Union University. Murray State University; M.S.N., Liberty University. Renee Anderson (2009). Assistant Professor, Director Charley Elliott ( ). -

2010-2012 University Bulletin

FISK UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE BULLETIN 2010 – 2012 1 MAILING ADDRESS INTERNET ADDRESS SWITCHBOARD Fisk University www.fisk.edu (615) 329-8500 1000 Seventeenth Avenue, North 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. CST Nashville, Tennessee 37208-3051 Monday through Friday ACCREDITATION Fisk University is accredited by The Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools to award the Bachelor of Arts (B.A.), Bachelor of Science (B.S.), Bachelor of Music (B.M.), Bachelor of Science in Nursing (B.S.N.) and Master of Arts (M.A.) degrees. Contact The Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call 404-679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Fisk University. Even before regional accreditation was available to African-American institutions, Fisk had gained recognition by leading universities throughout the nation and by such agencies as the Board of Regents of the State of New York, thereby enabling Fisk graduates' acceptance into graduate and professional schools. In 1930, Fisk became the first African-American institution to gain accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. It was also the first African-American institution to be placed on the approved lists of the Association of American Universities (1933) and the American Association of University Women (1948). In 1953, Fisk received a charter for the first Phi Beta Kappa chapter on a predominantly black campus and also became the first private, black college accredited by the National Association of Schools of Music. Fisk also holds memberships in the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education. -

TN 3. Association of Infant Mental Health in TN 4. Ayers Foundation 5

ESSER State Plan Stakeholder Outreach and Engagement Below is the list of stakeholder groups we reached out to directly requesting input: 1. Agape 2. American Federation for Children- TN 3. Association of Infant Mental Health in TN 4. Ayers Foundation 5. Benwood Foundation 6. Big Brothers Big Sisters Tennessee Statewide Association 7. Bill and Crissy Haslam Foundation 8. Boys and Girls Clubs in Tennessee 9. Chattanooga 2.0/Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce 10. Communities in Schools of Tennessee 11. Community Foundation of Greater Chattanooga 12. Community Foundation of Greater Memphis 13. Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee 14. Conexion Americas 15. Cookeville-Putnam County Chamber of Commerce 16. Country Music Association Foundation 17. East Tennessee Foundation 18. Education Preparation Providers (22) 19. Education Trust 20. Gates Foundation 21. Governor's Early Literacy Foundation 22. Hyde Foundation 23. Jackson Chamber of Commerce 24. Jason Foundation 25. Kingsport Chamber of Commerce 26. Knox Education Foundation 27. Knoxville Area Chamber of Commerce 28. Memphis Chamber of Commerce 29. Memphis Education Fund 30. Memphis Lift 31. Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce 32. Nashville Propel 33. Nashville Public Education Foundation 34. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People – Tennessee Chapter 35. Niswonger Foundation 36. Principal Study Council - Executive and Steering Committees 37. Professional Educators of Tennessee 38. Public Education Foundation 39. Scarlett Foundation 40. SCORE 41. Three Superintendent Engagement Groups 42. Superintendent Study Council Executive Committee 43. Synchronus Health 44. Teacher Advisory Council 45. Tennesseans for Quality Early Education 46. Tennesseans for Student Success 47. Tennessee Association of School Personnel Administrators 48. Tennessee Business Roundtable 49. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Kinsley Kelley Kiningham Business Address: 1900 Belmont Boulevard Belmont University College of Pharmacy Nashville, TN 37212-3757 (615)-460-8128 (office) (615)-460-6537 (fax) [email protected] Biographical Sketch Education 1989-1996 Ph.D. Toxicology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 1986-1989 M.S. Chemistry, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN 1982-1986 B.S. Chemistry/Biology, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN Professional Appointments 2015 Professor; Department of Pharmaceutical, Administrative and Social Sciences, Belmont University College of Pharmacy 2012-Present Assistant Dean of Student Affairs, Belmont College of Pharmacy 2009-Present Associate Professor, Dept. of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Belmont University College of Pharmacy 2006-2008 Associate Professor, Dept. of Pharmacology, Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine, Marshall University 2002-2006 Assistant Professor, Dept. of Pharmacology, Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine, Marshall University 1999-2002 Research Assistant Professor, University of Kentucky 1996-1999 Postdoctoral Scholar, University of Kentucky Honors & Awards 2013 Rho Chi 2013 Most Influential Faculty Member, Class of 2013 Hooding Ceremony, Belmont University 2013 Presidential Faculty Achievement Award Recipient 2012 Presidential Faculty Achievement Award Finalist 2011 Health Information Technology Scholar 2007 Delta Kappa Gamma Honorary Women’s Teaching Sorority 2005 Graduate Faculty Achievement Award 2004 Who’s Who in Medical Sciences Education -

Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(A) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 14A Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No. ) Filed by the Registrant ☒ Filed by a Party other than the Registrant ☐ Check the appropriate box: ☐ Preliminary Proxy Statement ☐ Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) ☒ Definitive Proxy Statement ☐ Definitive Additional Materials ☐ Soliciting Material Pursuant to §240.14a-12 CoreCivic, Inc. (Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if other than the Registrant) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): ☒ No fee required. ☐ Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11. (1) Title of each Class of securities to which transaction applies: (2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: (3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): (4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: (5) Total fee paid: ☐ Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. ☐ Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. Identify the previous filing by registration statement number, or the Form or Schedule and the date of its filing. (1) Amount Previously Paid: (2) Form, Schedule or Registration Statement No.: (3) Filing Party: (4) Date Filed: March 30, 2021 To our Stockholders: We invite you to attend the 2021 Annual Meeting of Stockholders (the “Annual Meeting”) of CoreCivic, Inc. -

RN/Prof Annual Report

TENNESSEE PROFESSIONAL SCHOOLS OF NURSING ENROLLMENT Associate Degree Programs School 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Aquinas College 214 147 62 0 0 Chattanooga State CC 302 366 317 332 302 Cleveland State CC 166 157 146 86 72 Columbia State CC 240 219 214 214 198 Concorde Career College 38 46 71 85 66 Dyersburg State CC 175 183 206 206 195 Excelsior College 777 156 474 284 Fortis Institute - Nashville 35 67 74 87 116 ITT Technical Institute - Nashville 253 78 Jackson State CC 303 284 267 235 223 Lincoln Memorial University 296 295 241 321 421 Motlow State CC 135 132 138 145 131 Nashville State CC 78 75 84 81 82 Northeast State CC 163 93 132 135 124 Pellissippi State CC 171 190 180 168 164 Roane State CC 197 187 191 188 216 Southern Adventist University 303 288 241 241 187 Southwest Tennessee CC 199 189 189 180 183 Tennessee State University 156 163 95 63 13 Walters State CC 253 249 250 243 257 TOTAL 3542 4185 3254 3484 3234 TENNESSEE PROFESSIONAL SCHOOLS OF NURSING ENROLLMENT BSN PROGRAMS Initial RN RN to School Licensure BSN 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 American Sentinel University 54 43 43 54 54 Aquinas College 0 0 19 26 65 107 0 0 Arkansas State University 41 2 10 27 242 41 Austin Peay State University 254 45 290 323 295 296 287 299 Baptist Memorial College of Hlth Sciences 370 28 496 526 504 480 473 398 Belmont University 619 3 552 574 503 609 411 622 Bethel University 49 11 54 75 70 78 80 60 Carson Newman College 107 15 101 111 116 92 106 122 Chamberlain College 92 14 65 87 92 Christian Brothers University 13 59 64 64 40 56 13 Cumberland -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS An Overview of the University ................................................................................................................................................3 2018-2019 Undergraduate Calendar........................................................................................................................................8 Student Life ...........................................................................................................................................................................13 Academic Program .................................................................................................................................................................17 Adult Studies .........................................................................................................................................................................29 Admissions .............................................................................................................................................................................31 Financial Information ............................................................................................................................................................39 Organization of the Curriculum ...........................................................................................................................................48 College of Arts and Sciences .................................................................................................................................................49 -

PCA College Profile 2.19

2018-2019 Welcome to Providence Christian Academy. EXCEPTIONAL FACULTY We are an inter-denominational Pre-K–12th grade school located in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Providence Christian Academy oers a classical 9:1 53 27 4 education from a Christian worldview. STUDENT - FACULTY FACULTY FACULTY TEACHER MEMBERS WITH WITH RATIO ADVANCED DOCTORATES 530 DEGREES 2018-2019 ENROLLMENT GRADING SCALE Grade Numerical Quality Pts Honors Duel Enrollment 2014/2015 2016/2017 A 90-100 4.0 4.5 5.0 338 365 B 80-89 3.0 3.5 4.0 2015/2016 2017/2018 C 70-79 2.0 2.5 3.0 350 476 F Below 70 0 0.0 0.0 GRADUATION REQUIREMENTS English 4 credits SPORTS History 4 credits 12 TSSAA Member School Math 4 credits Science 4 credits DUAL ENROLLMENT Theology 2 credits Foreign Language 2 credits Composition I and II Biblical World View Rhetoric 1 credit General Psychology Anatomy & Physiology Fine/Performing Arts 1 credit Biology I and II Greek I and II PE/Wellness 1 credit Dual enrollment classes oered varies by year Personal Finance .5 credit Logic .5 credit PROVIDENCE SERVICE Senior Thesis 1 credit 4,305 235 Average Average National National SERVICE HOURS COMMUNITY Merit Merit ACT SAT 2010-2016 2010-2016 2015-2018 SERVICE PROJECTS 25 1280 2 4 FULLY ACCREDITED BY Class of 2018 Class of 2018 Finalist Commended Our mission is to teach students to seek God’s truth and equip them with the tools for a lifetime of learning. COLLEGE ACCEPTANCES William R. Mott, Ph.D. Classes of 2010-2018 Head of School Colleges Accepted into Dierent Colleges 50 Attended 60 Andy Sheets, M.Ed.