Coverage of Trent Lott's Remarks at Strom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stepping up to the Challenge of Leadership on Race

STEPPING UP TO THE CHALLENGE OF LEADERSHIP ON RACE Anthony C. Thompson* I. INTRODUCTION First and foremost, I want to thank you for inviting me to deliver this keynote address. I applaud your choice to participate in a conference on difference and leadership because these are critical issues that deserve our best thinking and our collective attention. I have watched with great interest as organizations from global businesses, to law schools, to court systems have begun embracing the concept of diversity and inclusion. Setting diversity and inclusion as operating goals in our institutions is long overdue and an important step toward addressing chronic equity issues in our society. But as I celebrate the attention and intention around such efforts, I also have a worry. I am concerned that, as we work toward the inclusion part of the effort, we are rushing a little too fast past the diversity component. As a country, we have been quite anxious to define diversity as “diversity of thought,” “diversity of experience,” and, yes, even “gender diversity” as a way of avoiding the difficulty and discomfort of examining racial diversity. But we, as lawyers and leaders, need to learn to get comfortable in that discomfort. Because as much as we might * Professor of Clinical Law, Faculty Director, Center on Race, Inequality, and the Law at New York University School of Law. I gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Filomen D’Agostino and Max Greenberg Research Fund at the New York University School of Law. I would like to thank Professor Kim Taylor-Thompson for her helpful comments on this project. -

Pdf, Accessed 17 December 2018

INVESTIGATING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TARGETED KILLING, AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM, AND KRIEGSRAISON: REPERCUSSIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL LAW THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE, FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCE, SCHOOL OF LAW AND GOVERNMENT, DUBLIN CITY UNIVERSITY IN FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY CATHERINE CONNOLLY B.A., M.A. SUPERVISOR: DR JAMES GALLEN July 2019 1 I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctor of Philosophy is entirely my own work, that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: Catherine Connolly Candidate No: 57412029 Date: 18 December 2018 2 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................6 Dedication ........................................................................................................................7 Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................8 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 11 Why is this thesis relevant and necessary? ........................................................................... -

The Evolution of Neo-Conservative Foreign Policy Agenda - from the Cold War to the New Millennium Selected Issues

AD AMERICAM Journal of American Studies Vol. 8, 2008 ISSN 1896-9461 ISBN 978-83-233-2533-8 Grzegorz Nycz THE EVOLUTION OF NEO-CONSERVATIVE FOREIGN POLICY AGENDA - FROM THE COLD WAR TO THE NEW MILLENNIUM SELECTED ISSUES I. THE ORIGINS 1. The history of American neo-conservatism begins in the 1960s with a group of in tellectuals from the liberal camp, who rejected the Cultural Revolution and the radi calism of the New Left. The intellectual leaders of the new movement, Norman Pod- horetz and Irving Kristol, as well as their allies and associates Nathan Glazer, Daniel Bell, Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Jeanne Kirkpatrick, among others, were later named “neo-conservatives” or “neocons” to emphasize the difference between “converted” leftist liberals and “regular” republican conservatives (Ehrman 2000: 50- -70). Notably, neo-conservatives formed their intellectual credo from the elements of many doctrines - including the thought of Hannah Arendt, Reinhold Niebuhr, Walter Lippman, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., and Leo Strauss. In general, they shared the view of the whole conservative camp, that the social crisis of the 1960s and 1970s was deep ened by the counterculture, which undermined the Judeo-Christian tradition in America and infected the roots of American society. The “regular” and “neo” conser vatives commonly believed that American society had been weakened by the effects of industrialization and suffered from the erosion of social relations, caused by the leftist-liberal campaign against religion and family. In matters of foreign policy the early neo-conservatives defended containment and anticommunism, strongly sup ported the alliance between America and Israel and raised the significance of moral issues in international policy (Podhoretz 1986, Kristol 1999, Ehrman 2000, Friedman 2005, Tokarski 2006). -

Yucaipa Companies

YUCAIPA COMPANIES: “POSTER CHILD FOR THE ILLS OF POLITICAL DONATIONS AND BUSINESS” Yucaipa is a holding company that invests across a wide range of industries—from groceries to logistics to magazine distribution. Ronald Burkle, chairman of Yucaipa, has been a multi-million fundraiser and donor for Bill and Hillary Clinton and in Bill Clinton’s post-presidency, Burkle has emerged as a close friend and rain- maker for the Clintons – and the friendship has been prosperous for both. “The mainstream business press beats up on [Burkle], essentially for buying access and influence among politicians and leaders of the pension funds that invest with him (FORBES included). ‘I basically became the poster child for the ills of political donations and business. It’s preposterous!’ Burkle protests.” [Forbes, 12/11/06] BILL CLINTON AND YUCAIPA 2006: Bill Clinton Has Guaranteed Payments “Over $1,000” From Yucaipa And Has Invested In Several Yucaipa Funds. Hillary’s financial disclosure report indicates that Bill Clinton has “over $1,000” in guaranteed payments from Yucaipa Global Holdings. Because the Clintons are not required to report the actual amount or any range of income that is more specific than “over $1,000” we do not know how much Bill has been compen- sated. Through WJC International Investments GP, Bill Clinton invests in Yucaipa Global Holdings and Yu- caipa Global Partnership. The Yucaipa Global Partnership Fund “invests in securities of corporations that con- duct significant operations in foreign countries.” Clinton reported interest income between $201-$1,000 from Yucaipa Global Holdings and between $1,001-$2,500 from Yucaipa Global Partnership Fund. -

The State of the News: Texas

THE STATE OF THE NEWS: TEXAS GOOGLE’S NEGATIVE IMPACT ON THE JOURNALISM INDUSTRY #SaveJournalism #SaveJournalism EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Antitrust investigators are finally focusing on the anticompetitive practices of Google. Both the Department of Justice and a coalition of attorneys general from 48 states and the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico now have the tech behemoth squarely in their sights. Yet, while Google’s dominance of the digital advertising marketplace is certainly on the agenda of investigators, it is not clear that the needs of one of the primary victims of that dominance—the journalism industry—are being considered. That must change and change quickly because Google is destroying the business model of the journalism industry. As Google has come to dominate the digital advertising marketplace, it has siphoned off advertising revenue that used to go to news publishers. The numbers are staggering. News publishers’ advertising revenue is down by nearly 50 percent over $120B the last seven years, to $14.3 billion, $100B while Google’s has nearly tripled $80B to $116.3 billion. If ad revenue for $60B news publishers declines in the $40B next seven years at the same rate $20B as the last seven, there will be $0B practically no ad revenue left and the journalism industry will likely 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 disappear along with it. The revenue crisis has forced more than 1,700 newspapers to close or merge, the end of daily news coverage in 2,000 counties across the country, and the loss of nearly 40,000 jobs in America’s newsrooms. -

John Podhoretz

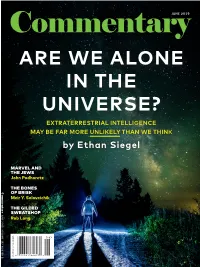

CommentaryJUNE 2019 ARE WE ALONE IN THE UNIVERSE? EXTRATERRESTRIAL INTELLIGENCE MAY BE FAR MORE UNLIKELY THAN WE THINK by Ethan Siegel MARVEL AND THE JEWS John Podhoretz THE BONES Commentary OF BRISK Meir Y. Soloveichik THE GILDED JUNE 2019 : VOLUME 147 NUMBER 6 147 : VOLUME JUNE 2019 SWEATSHOP Rob Long $5.95 US : $7.00 CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 JUNE 2019 COVER.indd 1 5/13/19 3:58 PM Acts of terror injure hundreds of Israelis. One act from you can save thousands. In Israel, only one agency is the official ambulance, disaster-response, and blood-services agency for the nation’s 9 million people. Yet, it’s not funded by the government. When you support Magen David Adom, you get the satisfaction of knowing your gift has impact. If you value life and want to make Israel a stronger, safer place, there’s no greater way than by supporting Magen David Adom. Save a life in Israel. Support Magen David Adom at afmda.org/one-act or call 866.632.2763. JUNE 2019 COVER.indd 2 5/13/19 3:57 PM EDITOR’S COMMENTARY The Human Miracle JOHN PODHORETZ UR EARTH WOULD BE so much better if it I think this notion has something to do with the didn’t have people, wouldn’t it? That notion— environmentalist downgrade of humanity over the past Owhat you might call a view of original sin ab- half century. Some of us can believe humanity is beyond sent possibility of redemption—is the hidden backbone salvation and the world would be better without it be- of radical environmentalism. -

The Brookings Institution

1 MOYNIHAN-2015/01/28 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION AN INSIDE VIEW OF THE AMERICAN PRESIDENCY: DANIEL PATRICK MOYNIHAN IN THE NIXON WHITE HOUSE Washington, D.C. Wednesday, January 28, 2015 PARTICIPANTS: Moderator: JULIE HIRSCHFELD DAVIS White House Correspondent The New York Times Featured Speaker: STEPHEN HESS Senior Fellow Emeritus, Governance Studies The Brookings Institution * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 2 MOYNIHAN-2015/01/28 P R O C E E D I N G S (Video played) MR. HESS: After that film, I need no introduction. (Laughter) The film has introduced me to you. I’m Steve Hess. That film, I love that little film. It was produced here at Brookings by our own George Burroughs. And I particularly like Nixon playing “Happy Birthday,” but I wish George had been able to include the next scene, which was Duke Ellington kissing the President French-style on both cheeks, Nixon blushing, et cetera. Now I get to introduce Julie, Julie Hirschfeld Davis. And what interested me, in a sense, was if we had had this event a year ago, when I had written a book called Whatever Happened to the Washington Reporters?, I would be interviewing Julie. In the nature of Washington, today she interviews more or less me. Because Julie -- SPEAKER: (inaudible) MR. HESS: Pardon? You’re working on the sound? I’m up and down. Up and down, up and down. (Laughter) I can talk louder, but I don’t know that that makes any difference. -

Social Media's Link with Individualism and the Dangers That Follow

Digital Commons @ Assumption University Honors Theses Honors Program 2021 Social Media's Link with Individualism and the Dangers that Follow Veronica Prytko Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.assumption.edu/honorstheses Part of the Political Science Commons, and the Social Media Commons SOCIAL MEDIA’S LINK WITH INDIVIDUALISM AND THE DANGERS THAT FOLLOW Veronica Prytko Faculty Supervisor: Geoffrey Vaughan, D. Phil Political Science A Thesis Submitted to Fulfill the Requirements of the Honors Program at Assumption College Fall 2020 2 Intro On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the Novel Coronavirus Disease a pandemic. The following days, the first lockdown were issued which closed all non- essential businesses and most people were advised to stay at home. As the months continued, lockdowns were gradually lifted and some non-essential businesses slowly started to open, but more recently states have been issuing in-state lockdowns and some people fear another lockdown could happen in the winter. During these lockdowns, one of the only means to connect with the outside world was through social media. Suddenly finding themselves with extra time, millions of Americans downloaded the top three apps of the time, TikTok, Zoom, and WhatsApp, to keep busy, stay employed, and order necessities to stay alive.1 All of these apps, among others, are a means to connect and interact with people. By watching videos, making Zoom calls, or texting their friends, people were finding ways to stay connected and have some type of social interaction. When Alexis de Tocqueville came to American in the 1830s, he observed “individualism” and concluded that it was needed for a modern democracies. -

Welfare Reform and Political Theory

WELFARE REFORM AND POLITICAL THEORY WELFARE REFORM AND POLITICAL THEORY LAWRENCE M. MEAD AND CHRISTOPHER BEEM EDITORS Russell Sage Foundation • New York The Russell Sage Foundation The Russell Sage Foundation, one of the oldest of America’s general purpose foundations, was established in 1907 by Mrs. Margaret Olivia Sage for “the improvement of social and living conditions in the United States.” The Founda- tion seeks to fulfill this mandate by fostering the development and dissemina- tion of knowledge about the country’s political, social, and economic problems. While the Foundation endeavors to assure the accuracy and objectivity of each book it publishes, the conclusions and interpretations in Russell Sage Founda- tion publications are those of the authors and not of the Foundation, its Trustees, or its staff. Publication by Russell Sage, therefore, does not imply Foundation endorsement. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Robert E. Denham, Chair Alan S. Blinder Larry V. Hedges Alan B. Krueger Christine K. Cassel Jennifer L. Hochschild Cora B. Marrett Thomas D. Cook Timothy A. Hultquist Eric Wanner Christopher Edley Jr. Kathleen Hall Jamieson Mary C. Waters John A. Ferejohn Melvin J. Konner Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Welfare reform and political theory / Lawrence M. Mead and Christopher Beem, editors. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-87154-595-0 1. Public welfare—United States. 2. Public welfare—Great Britain. 3. Welfare recipients—Employment—United States. 4. Welfare recipients—Employment— Great Britain. 5. United States—Social policy—1993- 6. Great Britain—Social policy—1979- 7. Public welfare—Political aspects. 8. Citizenship. I. Mead, Lawrence M. II. -

The Society of Professional Journalists Foundation Board Of

The Society of Professional Journalists Foundation Board of Directors Meeting Sept. 6, 2019 9 a.m. to Noon CDT San Antonio Grand Hyatt, Lone Star B San Antonio The foundation's mission is to perpetuate a free press as a cornerstone of our nation and our liberty. To ensure that the concept of self-government outlined by the Constitution survives and flourishes, the American people must be well informed. They need a free press to guide them in their personal decisions and in the management of their local and national communities. It is the role of journalists to provide fair, balanced and accurate information in a comprehensive, timely and understandable manner. AGENDA SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS FOUNDATION BOARD MEETING SAN ANTONIO GRAND HYATT, Lone Star A DATE: Sept. 6, 2019 TIME: 9 a.m. – Noon CDT 1. Call to order – Gratz 2. Roll Call – Albarado a. Gratz k. Evensen u. Leger b. Limor l. Fletcher v. Lehrman c. Albarado m. Gillman w. LoMonte d. Dubin n. Hall x. Gallagher Newberry e. Batts o. Hawes y. Pulliam f. Bethea p. Hsu z. Ross g. Bolden q. Jones aa. Schotz h. Brown r. Ketter bb. Tarquinio i. Carlson s. Kirtley j. Cuillier t. Kopen Katcef 3. Approval of minutes – Albarado Enter Executive Session 4. Talbott Talent Report – Leah York, Heather Rolinski Exit Executive Session 5. Remembering John Ensslin – Gratz 6. Foundation President’s Report – Gratz 7. SPJ President’s Report – Tarquinio 8. Treasurer’s Report – Dubin 9. Journalist on Call – Rod Hicks 10. Committee Reports – Gratz 11. Bylaws change – Gratz 12. Election 2 a. -

Boston College Law School Magazine Fall 1998 Boston College Law School

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Magazine 10-1-1998 Boston College Law School Magazine Fall 1998 Boston College Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclsm Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Boston College Law School, "Boston College Law School Magazine Fall 1998" (1998). Boston College Law School Magazine. Book 12. http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclsm/12 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. P UB LICATION NOTE BOSTON COLLEGE LAw SCHOOL INTERIM D EAN James S. Rogers DIRECroR OF INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT Deborah Blackmore Abrams EDITOR IN C HIEF Vicki Sanders CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Vijaya Andra Suzanne DeMers Michael Higgins Carla McDonald Kim Snow Abby Wolf Boston College Law School Magazine On the Cover: welcomes readers' comments. Yo u may comac[ us by phone at (6 17) 552-2873; by mail at Photographer Susan Biddle captures Boston Coll ege Law School, Barat House, 885 Centre Street, Newton. MA 02459- 11 63; Michael Deland in the autumn sunlight or bye-mail at [email protected]. at the FOR Memorial in Washington, DC. Copyright 1998, Boston Coll ege Law School. All publicatio n rights reserved. Opinions expressed in Boston College Law School Magazine do not necessar ily refl ecr the views of Boston College Law School or Boston College. -

The Filibuster and Reconciliation: the Future of Majoritarian Lawmaking in the U.S

The Filibuster and Reconciliation: The Future of Majoritarian Lawmaking in the U.S. Senate Tonja Jacobi†* & Jeff VanDam** “If this precedent is pushed to its logical conclusion, I suspect there will come a day when all legislation will be done through reconciliation.” — Senator Tom Daschle, on the prospect of using budget reconciliation procedures to pass tax cuts in 19961 Passing legislation in the United States Senate has become a de facto super-majoritarian undertaking, due to the gradual institutionalization of the filibuster — the practice of unending debate in the Senate. The filibuster is responsible for stymieing many legislative policies, and was the cause of decades of delay in the development of civil rights protection. Attempts at reforming the filibuster have only exacerbated the problem. However, reconciliation, a once obscure budgetary procedure, has created a mechanism of avoiding filibusters. Consequently, reconciliation is one of the primary means by which significant controversial legislation has been passed in recent years — including the Bush tax cuts and much of Obamacare. This has led to minoritarian attempts to reform reconciliation, particularly through the Byrd Rule, as well as constitutional challenges to proposed filibuster reforms. We argue that the success of the various mechanisms of constraining either the filibuster or reconciliation will rest not with interpretation by † Copyright © 2013 Tonja Jacobi and Jeff VanDam. * Professor of Law, Northwestern University School of Law, t-jacobi@ law.northwestern.edu. Our thanks to John McGinnis, Nancy Harper, Adrienne Stone, and participants of the University of Melbourne School of Law’s Centre for Comparative Constitutional Studies speaker series. ** J.D., Northwestern University School of Law (2013), [email protected].