Wolfram Von Eschenbach, Parzival1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Difference the Middle Ages Makes: Color and Race Before the Modern World

JMEMS31.1-01 Hahn 2/26/01 6:55 PM Page 1 a The Difference the Middle Ages Makes: Color and Race before the Modern World Thomas Hahn University of Rochester Rochester, New York The motives for gathering the present cluster of essays stem, in part, from the session “Race in the Middle Ages” that took place during the Interna- tional Congress on Medieval Studies in Kalamazoo in 1996. The event, sponsored by the Teachers for a Democratic Society, featured Michael Awk- ward, then Professor of English and Director of the Institute for African- American Studies at the University of Michigan, and included a brief response by me.1 Professor Awkward, an Americanist with little professional interest in medieval studies, had nonetheless agreed to address this session on race, presenting the lecture “Going Public: Ruminations on the Black Public Sphere.” This session, in prospect and panic, and in retrospect and reflection, urgently raised the question for me as a medievalist, What’s race got to do with it? What, if anything, does medieval studies have to do with racial discourses? Awkward’s appearance at Kalamazoo, unusual from several perspec- tives, had a double effect, for in providing an immediate, even urgent, perhaps arbitrary forum for discussion, it also pointed up the prevailing lack of interest in race among medievalists. What would he do, what was he doing—the nonmedievalist, the “expert” on race—at a conference that, among those who care, is a byword for dedicated, extensive (and to some degree exclusive) study of all things medieval? Within the identity politics that obtains throughout American society, the position he occupied as a per- son of color defined his relation to his subject and endowed him with exis- tential and political warrants that few at that particular conference might claim. -

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples Mittelalter (1150- Wolfram von Eschenbach Epik Parzival (1200/1210) 1450) Gottfried von Straßburg Tristan (ca. 1210) Hartmann von Aue Der arme Heinrich (ca. 1195) Johannes von Tepl Der Ackermann aus Böhmen (ca. 1400) Walther von der Vogelweide Lieder, Oskar von Wolkenstein Minnelyrik, Spruchdichtung Gedichte Renaissance Martin Luther Prosa Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen (1530) (1400-1600) Von der Freyheit eynis Christen Menschen (1521) Historia von D. Johann Fausten (1587) Das Volksbuch vom Eulenspiegel (1515) Der ewige Jude (1602) Sebastian Brant Das Narrenschiff (1494) Barock (1600- H.J.C. von Grimmelshausen Prosa Der abenteuerliche Simplizissimus Teutsch (1669) 1720) Schelmenroman Martin Opitz Lyrik Andreas Gryphius Paul Fleming Sonett Christian v. Hofmannswaldau Paul Gerhard Aufklärung (1720- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Prosa Fabeln 1785) Christian Fürchtegott Gellert Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Drama Nathan der Weise (1779) Bürgerliches Emilia Galotti (1772) Trauerspiel Miss Sara Samson (1755) Lustspiel Minna von Barnhelm oder das Soldatenglück (1767) 2 Sturm und Drang Johann Wolfgang Goethe Prosa Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (1774) (1767-1785) Johann Gottfried Herder Von deutscher Art und Kunst (selections; 1773) Karl Philipp Moritz Anton Reiser (selections; 1785-90) Sophie von Laroche Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim (1771/72) Johann Wolfgang Goethe Drama Götz von Berlichingen (1773) Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz Der Hofmeister oder die Vorteile der Privaterziehung (1774) -

Religion and Religious Symbolism in the Tale of the Grail by Three Authors

Faculty of Arts English and German Philology and Translation & Interpretation COMPARATIVE LITERATURE: RELIGION AND RELIGIOUS SYMBOLISM IN THE TALE OF THE GRAIL BY THREE AUTHORS by ASIER LANCHO DIEGO DEGREE IN ENGLISH STUDIES TUTOR: CRISTINA JARILLOT RODAL JUNE 2017 ABSTRACT: The myth of the Grail has long been recognised as the cornerstone of Arthurian literature. Many studies have been conducted on the subject of Christian symbolism in the major Grail romances. However, the aim of the present paper is to prove that the 15th-century “Tale of the Sangrail”, found in Le Morte d’Arthur, by Thomas Malory, presents a greater degree of Christian coloration than 12th-century Chrétien de Troyes’ Perceval and Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival. In order to evaluate this claim, the origin and function of the main elements at the Grail Ceremony were compared in the first place. Secondly, the main characters’ roles were examined to determine variations concerning religious beliefs and overall character development. The findings demonstrated that the main elements at the Grail Ceremony in Thomas Malory’s “The Tale of the Sangrail” are more closely linked to Christian motifs and that Perceval’s psychological development in the same work conflicts with that of a stereotypical Bildungsroman, in contrast with the previous 12th-century versions of the tale. Keywords: The Tale of the Grail, Grail Ceremony, Holy Grail, Christian symbolism INDEX 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... -

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021 Please Note: due to production considerations, duration for each production is subject to change. Please consult associated cue sheet for final cast list, timings, and more details. Please contact [email protected] for more information. PROGRAM #: OS 21-01 RELEASE: June 12, 2021 OPERA: Handel Double-Bill: Acis and Galatea & Apollo e Dafne COMPOSER: George Frideric Handel LIBRETTO: John Gay (Acis and Galatea) G.F. Handel (Apollo e Dafne) PRESENTING COMPANY: Haymarket Opera Company CAST: Acis and Galatea Acis Michael St. Peter Galatea Kimberly Jones Polyphemus David Govertsen Damon Kaitlin Foley Chorus Kaitlin Foley, Mallory Harding, Ryan Townsend Strand, Jianghai Ho, Dorian McCall CAST: Apollo e Dafne Apollo Ryan de Ryke Dafne Erica Schuller ENSEMBLE: Haymarket Ensemble CONDUCTOR: Craig Trompeter CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Chase Hopkins FILM DIRECTOR: Garry Grasinski LIGHTING DESIGNER: Lindsey Lyddan AUDIO ENGINEER: Mary Mazurek COVID COMPLIANCE OFFICER: Kait Samuels ORIGINAL ART: Zuleyka V. Benitez Approx. Length: 2 hours, 48 minutes PROGRAM #: OS 21-02 RELEASE: June 19, 2021 OPERA: Tosca (in Italian) COMPOSER: Giacomo Puccini LIBRETTO: Luigi Illica & Giuseppe Giacosa VENUE: Royal Opera House PRESENTING COMPANY: Royal Opera CAST: Tosca Angela Gheorghiu Cavaradossi Jonas Kaufmann Scarpia Sir Bryn Terfel Spoletta Hubert Francis Angelotti Lukas Jakobski Sacristan Jeremy White Sciarrone Zheng Zhou Shepherd Boy William Payne ENSEMBLE: Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, -

{Download PDF} Parzival

PARZIVAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Wolfram von Eschenbach, A. T. Hatto | 448 pages | 20 Nov 1980 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140443615 | English | London, United Kingdom bibliotheca Augustana Kundry, who serves the knights—she also serves the evil sorcerer Klingsor—has brought herbs from Arabia, hoping they will heal him. Amfortas, brought in on a litter, is not optimistic. He also explains how Amfortas came to be wounded by Klingsor and how Klingsor managed to seize the spear. A dying swan falls from the sky, and the youth who shot the swan arrives. Gurnemanz scolds the youth, who protests that he did not know it was wrong to shoot the bird. The youth—Parsifal—knows nothing of the world, not even his own origins. Gurnemanz, wondering whether he has found the hoped-for pure and innocent man, brings Parsifal into the castle. Amfortas feels unequal to the task, though it is carried out. Parsifal shows no interest in the proceedings, and an angry Gurnemanz sends him from the hall. Klingsor summons Kundry to his castle, and she reluctantly appears. He declares that she must assist him in defeating an opponent, and he demands that she change herself into an irresistible temptress. In such a form, she had helped Klingsor to best—and gravely wound—Amfortas. When Kundry appears, the other women leave. As Kundry tells Parsifal of his parents, she begins her own attempt at seduction. When she kisses Parsifal, however, she awakens in him not only passion but also knowledge. Klingsor appears and casts the spear at Parsifal. Parsifal catches it in midair and makes the sign of the cross with it. -

The Influence of Ludwig Feuerbach's Philosophy

1 THE INFLUENCE OF LUDWIG FEUERBACH’S PHILOSOPHY UPON THE LIBRETTO OF RICHARD WAGNER’S MUSIC-DRAMA ‘PARSIFAL’ By Paul Heise Research Consultant – The Richard Wagner Society of Florida [email protected] Home Tel: 727-343-0365 Home Add: 2001 55TH St. South Gulfport, FL 33707 ELABORATION OF A TALK PRESENTED TO THE BOSTON WAGNER SOCIETY ON 5/30/07, AT THE WELLESLEY FREE LIBRARY While it is well known that the atheist German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach’s influence upon Richard Wagner’s libretto for his music-drama The Ring of The Nibelung is great, it is usually assumed that Feuerbach’s influence upon Wagner’s writings and operas dropped off radically after his 1854 conversion to the pessimist philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. For this reason the librettos of Wagner’s other mature music- dramas completed after 1854, namely, Tristan and Isolde, The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, and Parsifal, are widely regarded as expressions of Wagner’s post-1854 Schopenhauerian phase. It is therefore quite surprising to find in key passages from the libretto of Wagner’s last work for the theater, Parsifal, a remarkable dependence on Feuerbachian concepts. This paper will examine that influence closely. A familiarity with the libretto of Parsifal is assumed. This paper has retained all the extracts from Feuerbach’s and Wagner’s writings (and recorded remarks) discussed in my original talk of 5/30/07. However, a number of key extracts which had to be dropped from the talk due to time constraints have been restored, and other extracts added, both to fill in logical gaps in the talk, and also to address certain questions posed by audience members after the talk. -

Power, Courtly Love, and a Lack of Heirs : Guinevere and Medieval Queens Jessica Grady [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 1-1-2009 Power, Courtly Love, and a Lack of Heirs : Guinevere and Medieval Queens Jessica Grady [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Grady, Jessica, "Power, Courtly Love, and a Lack of Heirs : Guinevere and Medieval Queens" (2009). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 69. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Power, Courtly Love, and a Lack of Heirs: Guinevere and Medieval Queens Thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Jessica Grady Dr. Laura Michele Diener, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Dr. David Winter, Ph.D. Dr. William Palmer, Ph.D. Marshall University December 2009 ABSTRACT Power, Courtly Love, and a Lack of Heirs: Guinevere and Medieval Queens by Jessica Grady Authors have given Queen Guinevere of the Arthurian stories a wide variety of personalities; she has been varyingly portrayed as seductive, faithful, “fallen,” powerful, powerless, weak-willed, strong-willed, even as an inheritor of a matriarchal tradition. These personalities span eight centuries and are the products of their respective times and authors much more so than of any historical Guinevere. Despite this, however, threads of similarity run throughout many of the portrayals: she had power in some areas and none in others; she was involved in a courtly romance; and she did not produce an heir to the throne. -

The Symbolism of the Holy Grail

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 1962 The symbolism of the Holy Grail : a comparative analysis of the Grail in Perceval ou Le Conte del Graal by Chretien de Troyes and Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach Karin Elizabeth Nordenhaug Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Nordenhaug, Karin Elizabeth, "The symbolism of the Holy Grail : a comparative analysis of the Grail in Perceval ou Le Conte del Graal by Chretien de Troyes and Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach" (1962). Honors Theses. 1077. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1077 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND LIBRARIES ~lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll3 3082 01028 5079 r THE SYMBOLISM OF THE HOLY GRAIL A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GRAIL In PERCEVAL ou LE CONTE del GRAAL by CHRETIEN de TROYES and PARZIVAL by WOLFRAM von ESCHENBACH by Karin Elizabeth Nordenhaug A Thesis prepared for Professor Wright In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Honors Program And in candidacy for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Westhampton College University of Richmond, Va. May 1962 P R E F A C E If I may venture to make a bold comparison, I have often felt like Sir Perceval while writing this thesis. Like. him, I set out on a quest for the Holy Grail. -

Introduction: to Be a Shapeshifter 1

NOTES Introduction: To Be a Shapeshifter 1 . Sir Thomas Malory, Malory: Works , ed. Eugene Vinaver (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978 ), 716. 2 . Carolyne Larrington, for example, points out that “Enchantresses . sometimes . support the aims of Arthurian chivalry, at other times they can be hostile and petty-minded.” See King Arthur’s Enchantresses: Morgan and Her Sisters in Arthurian Tradition (New York: I. B. Taurus, 2007), 2. While Larrington’s book provides a review of many of Morgan’s literary appearances, my study focuses on close reading, attention to translation issues, and discussion of social concerns. In her review of Larrington’s King Arthur’s Enchantresses: Morgan and Her Sisters in Arthurian Tradition , Elizabeth Archibald laments that “it would have been interesting to hear more about the ways in which Arthurian enchantresses do or do not resemble their Classical precursors, or indeed Celtic ones, in their use of magic and in their challenges to male heroic norms.” See Elizabeth Archibald, “Magic School,” Times Literary Supplement (February 2, 2007), 9. My study answers this cri- tique by reexamining pivotal scenes in critical texts and by dismantling the archetypal approach that Larrington follows. 3 . Norris J. Lacy, ed., The Fortunes of King Arthur (New York: D. S. Brewer, 2005 ), 94–95. 4 . Helaine Newstead, Bran the Blessed in Arthurian Romance (New York: AMS Press, 1966 ), 149. 5 . Elisa Marie Narin, “‘Þat on . Þat oÞer’: Rhetorical Descriptio and Morgan La Fay in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight ,” Pacific Coast Philology 23 (1988): 60–66. Morgan only partly fits the description of a supernatural ‘enemy’ provided by Hilda Ellis Davidson and Anna Chaudri; see n. -

Weekly Schedule

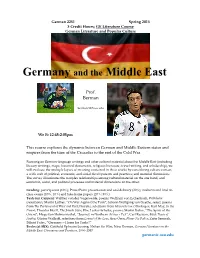

German 2251 Spring 2015 3 Credit Hours; GE Literature Course German Literature and Popular Culture and the Germany Middle East Prof. Berman [email protected] We Fr 12:45-2:05pm This course explores the dynamic between German and Middle Eastern states and empires from the time of the Crusades to the end of the Cold War. Focusing on German-language writings and other cultural material about the Middle East (including literary writings, maps, historical documents, religious literature, travel writing, and scholarship), we will evaluate the multiple layers of meaning contained in these works by considering culture contact; a wide web of political, economic, and social developments and practices; and material dimensions. The survey illuminates the complex relationships among cultural material on the one hand, and economic, social, and political processes and material dimensions on the other. Grading: participation (10%); PowerPoint presentation and oral delivery (20%); midterm and final in- class exams (10%, 10%) and take-home papers (20%; 30%). Texts (on Carmen): Walther von der Vogelweide, poems; Wolfram von Eschenbach, Willehalm (selections); Martin Luther, “On War Against the Turk”; Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, select. poems from The Parliament of West and East; Novalis, selections from Heinrich von Ofterdingen; Karl May, In the Desert; Theodor Herzl, The Jewish State; Else Lasker-Schüler, poems; Martin Buber, “The Spirit of the Orient”; Hugo von Hofmannsthal, “Journey in Northern Africa – Fez”; Carl Raswan, Black Tents of Arabia; Günter Wallraff, selections from Lowest of the Low; Aras Ören, Please No Police; Zafer Senocak, Bülent Tulay, “Germany—Home for Turks?” Books (at SBX): Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Nathan the Wise; Nina Berman, German Literature on the Middle East: Discourses and Practices, 1000-1989 germanic.osu.edu . -

German Studies MA Exam Departmental Reading List

Note: The book or film may be placed on reserve. Please check the catalog for the location and status. UC Library catalog search by call number. Note: The book or film may be placed on reserve. Please check the catalog for the location and status. UC Library catalog search by call number. German Studies MA Exam Departmental Reading List The reading list for the MA exam consists of four sections covering German literature and film from the Middle Ages to the 21st century. Section I - Medieval Period (750-1500) Author Call # Author or subject searches for related additional readings Hildebrandslied Langsam Oversize PF3987 .H5 1945, - In Runic and heroic poems of the old Teutonic peoples, ed. by Bruce Dickins Langsam Stacks PN831 .D5 - In Warnlieder SW Depository PT1392 .B4 bd 2 Heliand Langsam stacks PF3999.A31 S8 c.3, PT1375 .A5 nr.4 9th ed Other editions available in Langsam and SW Depository Otfried Evangelienbuch Otfrid, von Weissenburg, 9th Langsam Stacks and SW Depository cent PF3989 .A1 1947 (multiple copies) Minnesang Minnesang vom Kürenberger bis Minnesingers (selections) Wolfram Langsam Stacks PT1421 .W4 Minnesang des 13. Jahrhunderts SW Depository PT1421 .K721 1962 EDV-Text von "Des Minnesangs Frühling" Langsam Stacks PT1421 .K7 1988 Index + Disk Des Minnesangs Frühling Langsam Stacks PT1421 .K7 1977 Bd.1 Spruchdichtung Mittelhochdeutsche Spruchdichtung (selections) Langsam Stacks PT227 .M6 Walther von der Walther, von der Vogelweide, Vogelweide 12th cent. (selections) Selected passages from the works of: Hartmann von Aue Langsam Stacks PT1534.E7 L4 1967 Hartmann, von Aue, 12th cent. (Erec) SW Depository PT1375 .A5 Nr.39 Author Call # Author or subject searches for related additional readings Wolfram von Langsam Stacks PT1375 .A5 nr.119, Wolfram, von Eschenbach, Eschenbach (Parzival) PT1682.P6 H4 1911 12th cent Gottfried von Langsam Stacks Gottfried, von Strassburg, Straßburg (Tristan) PT1375 .D37 Bd.7-8 13th cent Langsam Stacks PT1525.A2 K7 1981 Bd. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Inhaltsverzeichnis. Klassiker des Mittelalters. Walther von der Vogelweide (gest. um 1230 in Würzburg) .... 1 Wolfram von Eschenbach (gest. Anfang des 13. Jahrhunderts. In Eschenbach begraben) 1 Das Nibelungenlied . 2 Das Gudrunlied 3 Klassiker des 18. Jahrhunderts. Friedrich Gottl. K lopsto ck (geb. 1724 zu Quedlinburg, gest. 1803 zu Hamburg) 4 Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (geb. 1729 zu Kamenz, Oberl., gest. 1781 zu Braunschweig) . 5 Johann Gottfried Herder (geb. 1744 zu Mohrnngeu, gest. 1803 zu Weimar) 6 Wolfgang von Goethe (geb. 1749 zu Frankfurt a. M., gest. 1832 zu Weimar) 7 Friedrich von Schiller (geb. 1759 zu Marbach, gest. 1805 zu Weimar) . 11 Friedrich Hebbel (geb. 1813 in Wesselburen, gest. 1863 in Wien) .... 16 Franz Grillparzer (geb. 1791 zu Wien, gest. 1872 zu Wien) 18 Bedeutung der Klassiker 19 Göttinger Dichterbund. Gottfried August Bürger (geb. 1747 zu Molmerschwende bei Harzgerode, gest. 1794 zu Göttingen) 19 Johann Heinrich Voß (geb. 1751 zu Sommersdyrf, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, gest. 1826 zu Heidelberg) 21 Matthias Claudius (geb. 1740 zu Reinfeld, Holstein, gest. 1815 p Hamburg) 22 Der Göttinger Dichterbund 22 Schwäbische Dichter. Ludwig Uhland (geb. 1787 zu Tübingen, gest. 1862 zu Tübingen) ... 23 Justinus Kerner (geb. 1786 zu Ludwigsburg, gest. 1862 zu Weinsberg) . 25 Gustav Schwab (geb. 1792 zu Stuttgart, gest. 1850 zu Stuttgart) ... 26 Eduard Mörike (geb. 1804 zu Ludwigsburg, gest. 1875 zu Stuttgart) . 26 Eigentümlichkeit der schwäbischen Dichter 26 Johann Peter Hebel (geb. 1760 zu Basel, gest. 1826 zu Schwetzingen) . 27 Dichter der Befreiungskriege. Ernst Moritz Arndt (geb. 1769 zu Schoritz, Rügen, gest. 1860 zu Bonn) 28 Max von Schenkendorf (geb. 1783 zu Tilsit, gest.