Zap-The-Rise-And-Fall-Of-Atari.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Video Game Consoles Introduction the First Generation

A History of Video Game Consoles By Terry Amick – Gerald Long – James Schell – Gregory Shehan Introduction Today video games are a multibillion dollar industry. They are in practically all American households. They are a major driving force in electronic innovation and development. Though, you would hardly guess this from their modest beginning. The first video games were played on mainframe computers in the 1950s through the 1960s (Winter, n.d.). Arcade games would be the first glimpse for the general public of video games. Magnavox would produce the first home video game console featuring the popular arcade game Pong for the 1972 Christmas Season, released as Tele-Games Pong (Ellis, n.d.). The First Generation Magnavox Odyssey Rushed into production the original game did not even have a microprocessor. Games were selected by using toggle switches. At first sales were poor because people mistakenly believed you needed a Magnavox TV to play the game (GameSpy, n.d., para. 11). By 1975 annual sales had reached 300,000 units (Gamester81, 2012). Other manufacturers copied Pong and began producing their own game consoles, which promptly got them sued for copyright infringement (Barton, & Loguidice, n.d.). The Second Generation Atari 2600 Atari released the 2600 in 1977. Although not the first, the Atari 2600 popularized the use of a microprocessor and game cartridges in video game consoles. The original device had an 8-bit 1.19MHz 6507 microprocessor (“The Atari”, n.d.), two joy sticks, a paddle controller, and two game cartridges. Combat and Pac Man were included with the console. In 2007 the Atari 2600 was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame (“National Toy”, n.d.). -

The Cowl Island/Page 19 Vol

BACK PAGE: Focus on student health Deanna Cioppa '07 Men's hoops win Think twice before going tanning for spring Are you getting enough sleep? Experts say reviews Trinity over West Virginia, break ... and get a free Dermascan in Ray extra naps could save your heart Hear Repertory Theater's bring Friars back Cafeteria this coming week/Page 4 from the PC health center/Page 8 latest, A Delicate into the running for Balance/Page 15 NCAA bid Est. 1935 Sarah Amini '07 Men's and reminisces about women’s track win riding the RIPTA big at Big East 'round Rhose Championships The Cowl Island/Page 19 Vol. LXXI No. 18 www.TheCowl.com • Providence College • Providence, R.I. February 22, 2007 Protesters refuse to be silenced by Jennifer Jarvis ’07 News Editor s the mild weather cooled off at sunset yesterday, more than 100 students with red shirts and bal loons gathered at the front gates Aof Providence College, armed with signs saying “We will not stop fighting for an end to sexual assault,” and “Vaginas are not vulgar, rape is vulgar.” For the second year in a row, PC students protested the decision of Rev. Brian J. Shanley, O.P., president of Providence College, to ban the production of The Vagina Monologues on 'campus. Many who saw a similar protest one year ago are asking, is this deja vu? Perhaps, but the cast and crew of The Vagina Monologues and many other sup porters said they will not stop protesting just because the production was banned last year. -

'Grand Theft Archive': a Quantitative Analysis of the State of Computer

Gooding, P. and Terras, M. (2008) "„Grand Theft Archive‟: a quantitative analysis of the current state of computer game preservation". The International Journal of Digital Curation. Issue 2, Volume 3, 2008. http://www.ijdc.net/ijdc/article/view/85/90 1 ‘Grand Theft Archive’: A Quantitative Analysis of the Current State of Computer Game Preservation Paul Gooding, Librarian, BBC Sports Library, London Melissa Terras, School of Library, Archive and Information Studies, University College London November 2008 Abstract Computer games, like other digital media, are extremely vulnerable to long-term loss, yet little work has been done to preserve them. As a result we are experiencing large-scale loss of the early years of gaming history. Computer games are an important part of modern popular culture, and yet are afforded little of the respect bestowed upon established media such as books, film, television and music. We must understand the reasons for the current lack of computer game preservation in order to devise strategies for the future. Computer game history is a difficult area to work in, because it is impossible to know what has been lost already, and early records are often incomplete. This paper uses the information that is available to analyse the current status of computer game preservation, specifically in the UK. It makes a quantitative analysis of the preservation status of computer games, and finds that games are already in a vulnerable state. It proposes that work should be done to compile accurate metadata on computer games and to analyse more closely the exact scale of data loss, while suggesting strategies to overcome the barriers that currently exist. -

Summer Is a Great Time to Enjoy Math Games and Reverse the Math

Summer is a great time to enjoy Math Games and reverse the Math 'Summer-Slide' Children enjoy a long summer vacation and play a lot of internet games on their own. Still they are on the lookout to have fun playing games with other kids or adults. Did you know kids lose on average 10 weeks of math knowledge over the summer? Usually referred to as the 'Math Slide'. There are many fun filled math summer camps that focus on math concepts using games and riddles instead of math facts. You can take action at home too: keep the patterns, shapes and numbers going to make sure kids love math. Enjoy playing board games, card games, dice, and domino games. Kids love to discuss their best strategies and to keep score, a math activity in itself. Hands-on board games are a great way to introduce younger kids to patterns an numbers. You can adapt the games to make sure all kids can participate, consider starting with counting and sorting everyday objects. For best math learning, in general do not emphasize speed until all math facts are memorized and easily retrieved (automatized), better ask what they think and share your strategies. Children enjoy making their own playing cards from note cards. Let them be creative with colored markers making dot patterns, shapes, numbers, money notations etc. use stickers etc. there are endless options, that all will add to the fun. You can use self made cards with dots or numbers or store bought playing cards in various ways to learn numbers, counting, and calculating while playing a game: 1. -

Rétro Gaming

ATARI - CONSOLE RETRO FLASHBACK 8 GOLD ACTIVISION – 130 JEUX Faites ressurgir vos meilleurs souvenirs ! Avec 130 classiques du jeu vidéo dont 39 jeux Activision, cette Atari Flashback 8 Gold édition Activision saura vous rappeler aux bons souvenirs du rétro-gaming. Avec les manettes sans fils ou vos anciennes manettes classiques Atari, vous n’avez qu’à brancher la console à votre télévision et vous voilà prêts pour l’action ! CARACTÉRISTIQUES : • 130 jeux classiques incluant les meilleurs hits de la console Atari 2600 et 39 titres Activision • Plug & Play • Inclut deux manettes sans fil 2.4G • Fonctions Sauvegarde, Reprise, Rembobinage • Sortie HD 720p • Port HDMI • Ecran FULL HD Inclut les jeux cultes : • Space Invaders • Centipede • Millipede • Pitfall! • River Raid • Kaboom! • Spider Fighter LISTE DES JEUX INCLUS LISTE DES JEUX ACTIVISION REF Adventure Black Jack Football Radar Lock Stellar Track™ Video Chess Beamrider Laser Blast Asteroids® Bowling Frog Pond Realsports® Baseball Street Racer Video Pinball Boxing Megamania JVCRETR0124 Centipede ® Breakout® Frogs and Flies Realsports® Basketball Submarine Commander Warlords® Bridge Oink! Kaboom! Canyon Bomber™ Fun with Numbers Realsports® Soccer Super Baseball Yars’ Return Checkers Pitfall! Missile Command® Championship Golf Realsports® Volleyball Super Breakout® Chopper Command Plaque Attack Pitfall! Soccer™ Gravitar® Return to Haunted Save Mary Cosmic Commuter Pressure Cooker EAN River Raid Circus Atari™ Hangman House Super Challenge™ Football Crackpots Private Eye Yars’ Revenge® Combat® -

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

How Much Does the 24 Game Increase the Recall of Arithmetic Facts?

How Much Does the 24 Game Increase the Recall of Arithmetic Facts? Jonquille Eley The City College of New York- CUNY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for EDSE 02011 for Dr. Eva Sattlberger December 14, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 3 INTRODUCTION 4-6 LITERATURE REVIEW 6-10 SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS 10-11 INTERVENTION 12-18 DATA COLLECTION 15-18 RESULTS 18-23 CONCLUSION 23-26 REFERENCES 26-28 ABSTRACT Sixth grade students come to MS 331 with strong mathematics backgrounds from elementary school. Nevertheless, students often come with a dearth of skills when performing basic math computations. The focus of this study is to investigate the use of the 24 Game in quickening the ability of sixth graders to perform basic computations. The game reinforces skills along with strategy when finding correct solutions. Students practiced the 24 Game largely on homework assignments and to a lesser extent, during instructional time. Students were measured on their ability to compute arithmetic facts on one minute assessments. Each class showed positive growth as the rigor of the quizzes increased due to 24 Game exposure after three weeks. Students who practiced the 24 Game most frequently on their homework scored the highest. Non-participants on average scored lower than participants. The 24 Game creates cooperation, stamina, and excitement through problem-solving. The speed and accuracy of arithmetic skills for sixth grade students improved through the study period. 3 INTRODUCTION Reaching lower-level students in the classroom requires varied instructional techniques. Games in the classroom break the monotony of book work and give students an opportunity to embrace other skill sets. -

Still Here Nearly Three Decades After It Opened in New York’S Battery Park City, This Small Site Continues to Spread Its Influence—And Bring People Joy

STILL HERE NEARLY THREE DECADES AFTER IT OPENED IN NEW YORK’S BATTERY PARK CITY, THIS SMALL SITE CONTINUES TO SPREAD ITS INFLUENCE—AND BRING PEOPLE JOY. BY JANE MARGOLIES / PHOTOGRAPHY BY LEXI VAN VALKENBURGH 102 / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE JUNE 2016 LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE JUNE 2016 / 103 rom Mary Miss’s home and studio, it’s Today much of New York’s waterfront has been civic purpose—something she has continued to a couple blocks south, then west, to developed with attractive and popular parks and pursue with the nonprofit she founded, City as reach Battery Park City, the landmark public spaces like this one. But South Cove— Living Laboratory. residential and commercial develop- conceived at a time when the shoreline was a Fment built on landfill just off Lower Manhattan. no-man’s-land, cut off from the rest of the city “To work on something on this scale—something Miss, an artist, is a walker, and when her dog by roadways and railroad tracks, and dotted with permanent that would affect the lives of New Yorkers was young and spry, they used to make the trek derelict warehouses—helped spark New York’s —that was an amazing experience,” she says. together regularly, wending their way down to ABOVE rediscovery of its waterfront. It gave those who The landfill area— South Cove, the small park along the Hudson still mostly undeveloped lived and worked in Manhattan a toehold on The three of them had never worked together River she designed with the landscape architect when this photograph the river. -

ATARI MEETS CONVENIENCE STORES TRIBUTE to ATARI Regional Sales Manager

Atari , Inc. 1265 Borregas, Sunnyvale, California 94086 Alan Inc. 1977 October, 1977 Volume I , Number 11 ATAI2I'S MAGIC Presented for the first time at AMOA, Canyon Bomber™ is a game with magnetic appeal. This one or two player video game creates the kind of player determination to achieve higher and higher scores. This means high replay and high collections. Bombs are dropped from blimps and planes traveling a t varying speeds over a canyon filled with targets. The objective is simple: Players try to hit all the targets in the canyon without missing to obtain Like magic, Atari presents the biggest the highest score. and best lineup of products ever at the Skill and timing are required as players 1977 trade shows. It will be the premiere decide when to drop the bombs in order of Airborne Avenger™, Destroyer™, to maximize the number of targets hit. Canyon Bomber™ , the 2 Game Game time is determined by the number Module TM, and even more new games of misses allowed, as set by the operator that will mystify you with their variety at 3, 4 , 5, or 6 per game. One player and appeal. against the computer, or two players At the Amusement and Musi c Opera against each other, Canyon Bomber is a tors Association Exposition, Oct. 28 - 30, competitive challenge. Atari will feature magical games and special entertainment at our booth in the West Room (16 - 23 and 26 - 33) of the Con rad Hilton in Chicago. Everyone is invited to preview our exciting products of the future and on Saturday you ca n meet Atari's Master of Magic. -

Dp Guide Lite Us

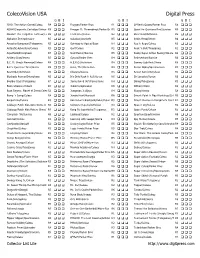

ColecoVision USA Digital Press GB I GB I GB I 2010: The Action Game/Coleco R4 Frogger/Parker Bros R1 Q*Bert's Qubes/Parker Bros R8 ADAM Diagnostic Cartridge/Coleco R9 Frogger II: Threeedeep!/Parker Br R5 Quest for Quintana Roo/Sunrise R5 Alcazar: The Forgotten Fortress/Te R2 Front Line/Coleco R2 River Raid/Activision R2 Alphabet Zoo/Spinnaker R5 Galaxian/Atarisoft R5 Robin Hood/Xonox R6 Amazing Bumpman/Telegames R5 Gateway to Apshai/Epyx R4 Roc ‘n Rope/Coleco R3 Antarctic Adventure/Coleco R3 Gorf/Coleco R2 Rock 'n Bolt/Telegames R2 Aquattack/Interphase R7 Gust Buster/Sunrise R5 Rocky Super Action Boxing/Coleco R2 Artillery Duel/Xonox R5 Gyruss/Parker Bros R4 Rolloverture/Sunrise R6 B.C. II: Grog's Revenge/Coleco R4 H.E.R.O./Activision R4 Sammy Lightfoot/Sierra R8 B.C.'s Quest for Tires/Sierra R3 Heist, The/Micro-Fun R4 Sector Alpha/Spectravision R7 Beamrider/Activision R4 Illusions/Coleco R5 Sewer Sam/Interphase R5 Blockade Runner/Interphase R6 It's Only Rock 'n Roll/Xonox R6 Sir Lancelot/Xonox R6 Boulder Dash/Telegames R7 James Bond 007/Parker Bros R4 Skiing/Telegames R5 Brain Strainers/Coleco R5 Jukebox/Spinnaker R6 Slither/Coleco R2 Buck Rogers: Planet of Zoom/Colec R2 Jumpman Jr./Epyx R4 Slurpy/Xonox R8 Bump 'n Jump/Coleco R4 Jungle Hunt/Atarisoft R6 Smurf: Paint 'n Play Workshop/Col R5 Burgertime/Coleco R3 Ken Uston's Blackjack/Poker/Colec R3 Smurf: Rescue in Gargamel's Castl R1 Cabbage Patch Kids Adventures in R3 Keystone Kapers/Activision R3 Space Fury/Coleco R2 Cabbage Patch -

Elec~Ronic Gantes Formerly Arcade Express

Elec~ronic Gantes Formerly Arcade Express Tl-IE Bl-WEEKLY ELECTRONIC GAMES NEWSLETTER VOLUME TWO, NUMBER NINE DECEMBER 4, 1983 SINGLE ISSUE PRICE $2.00 ODYSSEY EXITS The company that created the home arcading field back in 1970 has de VIDEOGAMING cided to pull in its horns while it takes its future marketing plans back to the drawing board. The Odyssey division of North American Philips has announced that it will no longer produce hardware for its Odyssey standard programmable videogame system. The publisher is expected to play out the string by market ing the already completed "War Room" and "Power Lords" cartridges for ColecoVision this Christmas season, but after that, it's plug-pulling time. Is this the end of Odyssey as a force in the gaming world? Only temporarily. The publisher plans to keep a low profile for a little while until its R&D department pushes forward with "Operation Leapfrog", the creation of N.A.P. 's first true computer. 20TH CENTURY FOX 20th Century Fox Videogames has left the game business, saying, THROWS IN THE TOWEL "Enough is enough!" According to Fox spokesmen, the canny company didn't actually experience any heavy losses. However, the foxy powers-that-be decided that the future didn't look too bright for their brand of video games, and that this is a good time to get out. The company, whose hit games included "M*A*S*H", "MegaForce", "Flash Gordon" and "Alien", reportedly does not have a large in ventory of stock on hand, and expects to experience no large financial losses as it exits the gaming business. -

Mayor's Economy

20091012-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 10/9/2009 7:34 PM Page 1 INSIDE REPORT TOP STORIES SMALL BUSINESS Enough shouting! The CIT grabs headlines, cold, hard facts on but local rivals health care reform grab its customers ® PAGE 17 PAGE 2 Brooklyn faces VOL. XXV, NO. 41 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM OCTOBER 12-18, 2009 PRICE: $3.00 looming luxury rentals A + B deluge C C PAGE 2 LOOK WHO Museums build big shows around single works of art REMADE Mayor’s PAGE 3 BURDEN. AND THEN SOME: economy: Why analysts see The city’s planner-in- chief will rezone her six more losing 100th neighborhood Grades quarters for Citi NEW YORK this week. IN THE MARKETS, PAGE 4 are in The strongest hand Socialite-slash-planning Bloomberg gets for Aqueduct casino commish Amanda Burden an A for quality of EDITORIAL, PAGE 10 has rezoned a fifth of the city, life, a C for budget championed good design and driven big developers nuts BY DANIEL MASSEY when mayor Michael Bloomberg BY THERESA AGOVINO announced last October that he wanted to change the law so he when amanda burden was 12, her step- could run for a third term,he argued father, CBS founder William Paley, that his experience as “a business- turned the front lawn of the family’s Man- man with expertise on Wall Street hasset, Long Island, home into a testing and finance” would help the city confront an unprecedented eco- ground. He littered the yard with massive nomic crisis. A year later, the local BUSINESS LIVES granite models of the skyscraper he was unemployment rate is 10.3%,a 16- GOTHAM GIGS building to house his company in mid- year high.