The End of the Road for the Indo-Greeks?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Maccabees, Chapter 1 Letter 1: 124 B.C

Archdiocese of St. Louis Office of Sacred Worship Lectio Divina Bible The Second Book of Maccabees Second Maccabees can be divided as follows: I. Letters to the Jews in Egypt II. Author’s Preface III. Heliodorus’ Attempt to Profane the Temple IV. Profanation and Persecution V. Victories of Judas and Purification of the Temple VI. Renewed Persecution VII. Epilogue * * * Lectio Divina Read the following passage four times. The first reading, simple read the scripture and pause for a minute. Listen to the passage with the ear of the heart. Don’t get distracted by intellectual types of questions about the passage. Just listen to what the passage is saying to you, right now. The second reading, look for a key word or phrase that draws your attention. Notice if any phrase, sentence or word stands out and gently begin to repeat it to yourself, allowing it to touch you deeply. No elaboration. In a group setting, you can share that word/phrase or simply pass. The third reading, pause for 2-3 minutes reflecting on “Where does the content of this reading touch my life today?” Notice what thoughts, feelings, and reflections arise within you. Let the words resound in your heart. What might God be asking of you through the scripture? In a group setting, you can share your reflection or simply pass. The fourth reading, pause for 2-3 minutes reflecting on “I believe that God wants me to . today/this week.” Notice any prayerful response that arises within you, for example a small prayer of gratitude or praise. -

Situation Report Nature of Hazard: Floods Current Situation

India SITUATION REPORT NATURE OF HAZARD: FLOODS In Maharashtra Bhandara and Gondia were badly affected but situation has improved there. Andhra Pradesh situation is getting better in Khamam, East and West Godavary districts. Road connectivity getting restored and Communication is improving. People from the camps have started returning back. Flood Situation is under control as the Rivers in Andhra Pradesh are flowing at Low Flood Levels. In Surat situation is getting much better as Tapi at Ukai dam is flowing with falling trend In Maharashtra River Godavari is flowing below the danger level. In Maharashtra Konkan and Vidharbha regions have received heavy rainfall. Rainfall in Koyna is recorded at 24.9mm and Mahableshwar 18mm in Santa Cruz in Mumbai it is 11mm. The areas which received heavy rainfall in last 24 hours in Gujarat are Bhiloda, Himatnagar and Vadali in Sabarkantha district, Vav and Kankrej in Banskantha district and Visnagar in Mehsana. IMD Forecast; Yesterday’s (Aug16) depression over Orissa moved northwestwards and lay centred at 0830 hours IST of today, the 17th August, 2006 near Lat. 22.00 N and Long. 83.50 E, about 100 kms east of Champa. The system is likely to move in a northwesterly direction and weaken gradually. Under its influence, widespread rainfall with heavy to very heavy falls at few places are likely over Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh during next 24 hours. Widespread rainfall with heavy to very heavy falls at one or two places are also likely over Orissa, Vidarbha and east Madhya Pradesh during the same period -

Seleucid Coinage and the Legend of the Horned Bucephalas

Seleucid coinage and the legend of the horned Bucephalas Autor(en): Miller, Richard P. / Walters, Kenneth R. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische numismatische Rundschau = Revue suisse de numismatique = Rivista svizzera di numismatica Band (Jahr): 83 (2004) PDF erstellt am: 04.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-175883 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch RICHARD P. MILLER AND KENNETH R.WALTERS SELEUCID COINAGE AND THE LEGEND OF THE HORNED BUCEPHALAS* Plate 8 [21] Balaxian est provincia quedam, gentes cuius Macometi legem observant et per se loquelam habent. Magnum quidem regnum est. Per successionem hereditariam regitur, quae progenies a rege Alexandra descendit et a filia regis Darii Magni Persarum... -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

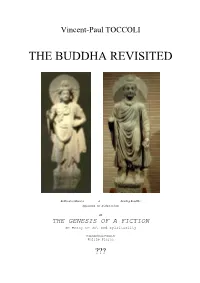

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

Intersecting Identities: Cultural and Traditional Allegiance in Portrait of an Emir

INTERSECTING IDENTITIES: CULTURAL AND TRADITIONAL ALLEGIANCE IN PORTRAIT OF AN EMIR Ariana Panbechi In Iranian history, the period between the eighteenth and early twentieth centuries can be best described as an era of monumental change. Transformations in economics, technology, military administration, and the arts reverberated across the Persian Empire and were further developed by the Qajar dynasty, which was quick to embrace the technological and industrial innovations of modernism. 1 However, the Qajars were also strongly devoted to tradition, and utilized customary Persian motifs and themes to craft an imperial identity that solidified their position as the successors to the Persian imperial lineage.2 This desire to align with the past manifested in the visual arts, namely in large-scale royal portraiture of the Qajar monarchy and ruling elite. Executed in 1855, Portrait of an Emir (Fig. 1) is a depiction of an aristocrat that represents the Qajar devotion to reviving traditional imagery through art in an attempt to craft a nationalist identity. The work portrays a Qajar nobleman dressed in lavish robes and seated on a two-tone carpet within a palatial setting. The subject is identified as Emir Qasem Khan in the inscription that appears to the left of his head.3 Figure 1. Attributed to Afrasiyab, Portrait of an Emir, 1855. Oil on cotton, 59 x 37 in. Brooklyn Museum, accession number 73.145. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles K. Wilkinson, Brooklyn, New York. Image courtesy the Brooklyn Museum. In this paper, I argue that Emir Qasem Khan’s portrait, as a pictorial representation of how he presented himself during his lifetime, is a visualization of the different entities, ideas, and traditions that informed his carefully crafted identity as a member of the Qajar court. -

ART XVI.—On the Identity of Xandrames and Krananda

447 ART XVI.—On the Identity of Xandrames and Krananda. By EDWARD THOMAS, ESQ. AT the meeting of the Royal Asiatic Society, on the 21st Nov., 1864,1 undertook the task of establishing the identity of the Xandrames of Diodorus Siculus and Quintus Curtius, the undesignated king of the Gangetic provinces of other Classic Authors—with the potentate whose name appears on a very extensive series of local mintages under the bilingual Bactrian and Indo-Pali form of Krananda. With the very open array of optional readings of the name afforded by the Greek, Latin, Arabic, or Persian tran- scriptions, I need scarcely enter upon any vindication for con- centrating the whole cifcle of misnomers in the doubly autho- ritative version the coins have perpetuated: my endeavours will be confined to sustaining the reasonable probability of the contemporaneous existence of Alexander the Great and the Indian Krananda; to exemplifying the singularly appro- priate geographical currency and abundance of the coins themselves; and lastly to recapitulating the curious evidences bearing upon Krananda's individuality, supplied by indi- genous annals, and their strange coincidence with the legends preserved by the conterminous Persian epic and prose writers, occasionally reproduced by Arab translators, who, however, eventually sought more accurate knowledge from purely Indian sources. In the course of this inquiry, I shall be in a position to show, that Krananda was the prominent representative of the regnant fraternity of the " nine Nandas," and his coins, in their symbolic devices, will demonstrate for us, what no written history, home or foreign, has as yet explicitly de- clared, that the Nandas were Buddhists. -

What the Romans Knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 • Part II

What the Romans knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know • Part II 1 What the Romans knew Archaic Roma Capitolium Forum 2 (Museo della Civiltà Romana, Roma) What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Wars against Carthage resulted in conquest of the Phoenician and Greek civilizations – Greek pantheon (Zeus=Jupiter, Juno = Hera, Minerva = Athena, Mars= Ares, Mercury = Hermes, Hercules = Heracles, Venus = Aphrodite,…) – Greek city plan (agora/forum, temples, theater, stadium/circus) – Beginning of Roman literature: the translation and adaptation of Greek epic and dramatic poetry (240 BC) – Beginning of Roman philosophy: adoption of Greek schools of philosophy (155 BC) – Roman sculpture: Greek sculpture 3 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Greeks: knowing over doing – Romans: doing over knowing (never translated Aristotle in Latin) – “The day will come when posterity will be amazed that we remained ignorant of things that will to them seem so plain” (Seneca, 1st c AD) – Impoverished mythology – Indifference to metaphysics – Pragmatic/social religion (expressing devotion to the state) 4 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Western civilization = the combined effect of Greece's construction of a new culture and Rome's destruction of all other cultures. 5 What the Romans Knew • The Mediterranean Sea (Mare Nostrum) – Rome was mainly a sea power, an Etruscan legacy – Battle of Actium (31 BC) created the “mare nostrum”, a peaceful, safe sea for trade and communication – Disappearance of piracy – Sea routes were used by merchants, soldiers, -

A Literary Sources

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Index More Information Index A Literary sources Livy XXVI.24.7–15: 77 (a); XXIX.12.11–16: 80; XXXI.44.2–9: 11 Aeschines III.132–4: 82; XXXIII.38: 195; XXXVII.40–1: Appian, Syrian Wars 52–5, 57–8, 62–3: 203; XXXVIII.34: 87; 57 XXXIX.24.1–4: 89; XLI.20: 209 (b); ‘Aristeas to Philocrates’ I.9–11 and XLII.29–30.7: 92; XLII.51: 94; 261 V.35–40: XLV.29.3–30 and 32.1–7: 96 15 [Aristotle] Oeconomica II.2.33: I Maccabees 1.1–9: 24; 1.10–25 and 5 7 Arrian, Alexander I.17: ; II.14: ; 41–56: 217; 15.1–9: 221 8 9 III.1.5–2.2: (a); III.3–4: ; II Maccabees 3.1–3: 216 12 13 IV.10.5–12.5: ; V.28–29.1: ; Memnon, FGrH 434 F 11 §§5.7–11: 159 14 20 V1.27.3–5: ; VII.1.1–4: ; Menander, The Sicyonian lines 3–15: 104 17 18 VII.4.4–5: ; VII.8–9 and 11: Menecles of Barca FGrHist 270F9:322 26 Arrian, FGrH 156 F 1, §§1–8: (a); F 9, Pausanias I.7: 254; I.9.4: 254; I.9.5–10: 30 §§34–8: 56; I.25.3–6: 28; VII.16.7–17.1: Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae V.201b–f, 100 258 43 202f–203e: ; VI.253b–f: Plutarch, Agis 5–6.1 and 7.5–8: 69 23 Augustine, City of God 4.4: Alexander 10.6–11: 3 (a); 15: 4 (a); Demetrius of Phalerum, FGrH 228 F 39: 26.3–10: 8 (b); 68.3: cf. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (As on 20.11.2020)

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (as on 20.11.2020) Sl. Year of State District Block/ Taluka Village/ Habitation Name of the School Status No. sanction 1 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Y. Ramavaram P. Yerragonda EMRS Y Ramavaram 1998-99 Functional 2 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Kodavalur Kodavalur EMRS Kodavalur 2003-04 Functional 3 Andhra Pradesh Prakasam Dornala Dornala EMRS Dornala 2010-11 Functional 4 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Gudem Kotha Veedhi Gudem Kotha Veedhi EMRS GK Veedhi 2010-11 Functional 5 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Buchinaidu Kandriga Kanamanambedu EMRS Kandriga 2014-15 Functional 6 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Maredumilli Maredumilli EMRS Maredumilli 2014-15 Functional 7 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Ozili Ojili EMRS Ozili 2014-15 Functional 8 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Meliaputti Meliaputti EMRS Meliaputti 2014-15 Functional 9 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Bhamini Bhamini EMRS Bhamini 2014-15 Functional 10 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Munchingi Puttu Munchingiputtu EMRS Munchigaput 2014-15 Functional 11 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Dumbriguda Dumbriguda EMRS Dumbriguda 2014-15 Functional 12 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Makkuva Panasabhadra EMRS Anasabhadra 2014-15 Functional 13 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Kurupam Kurupam EMRS Kurupam 2014-15 Functional 14 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Pachipenta Guruvinaidupeta EMRS Kotikapenta 2014-15 Functional 15 Andhra Pradesh West Godavari Buttayagudem Buttayagudem EMRS Buttayagudem 2018-19 Functional 16 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Chintur Kunduru EMRS Chintoor 2018-19 Functional