A Monastery in a Sociological Perspective: Seeking for a New Approach Marcin Jewdokimow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christian Saṃnyāsis and the Enduring Influence of Bede Griffiths in California

3 (2016) Miscellaneous 3: AP-BI Christian Saṃnyāsis and the Enduring Influence of Bede Griffiths in California ENRICO BELTRAMINI Department of Religious Studies, Santa Clara University, California, USA © 2016 Ruhr-Universität Bochum Entangled Religions 3 (2016) ISSN 2363-6696 http://dx.doi.org/10.13154/er.v3.2016.AP-BI Enrico Beltramini Christian Saṃnyāsis and the Enduring Influence of Bede Griffiths in California ENRICO BELTRAMINI Santa Clara University, California, USA ABSTRACT This article thematizes a spiritual movement of ascetic hermits in California, which is based on the religious practice of Bede Griffiths. These hermits took their religious vows in India as Christian saṃnyāsis, in the hands of Father Bede, and then returned to California to ignite a contemplative renewal in the Christian dispirited tradition. Some tried to integrate such Indian tradition in the Benedictine order, while others traced new paths. KEY WORDS Bede; Griffiths; California; saṃnyāsa; Camaldoli; Christianity Preliminary Remarks— Sources and Definitions The present paper profited greatly from its main sources, Sr. Michaela Terrio and Br. Francis Ali, hermits at Sky Farm Hermitage, who generously shared with me their memories of Bede Griffiths as well as spiritual insights of their life of renunciation as Christian saṃnyāsis in California. Several of the personalities mentioned in this article are personally known to the author. I offer a definition of the main terms used here:saṃnyāsis ‘ ’ are the renouncers, the acosmic hermits in the tradition of the Gītā; ‘saṃnyāsa’ is the ancient Indian consecration to acosmism and also the fourth and last stage (aśhrama) in the growth of human life; ‘guru’ is a polysemic word in India; its theological meaning depends on the religious tradition. -

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

The Divine Office

THE DIVINE OFFICE BRO. EMMANUEL NUGENT, 0. P. PIRITUAL life must be supplied by spiritual energy. An efficient source of spiritual energy is prayer. From Holy Scripture we learn that we should pray always. li In general, this signifies that whatever we do should be done for the honor and glory of God. In a more restricted sense, it requires that each day be so divided that at stated in tervals we offer to God acts of prayer. From a very early period it has been the custom of the Church, following rather closely the custom that prevailed among the Chosen People, and later among the Apostles and early Christians, to arrange the time for her public or official prayer as follows: Matins and Lauds (during the night), Prime (6 A.M.), Tierce (9 A.M.), Sext (12M.), None (3 P.M.), Vespers (6 .P. M.), Compline (nightfall). The Christian day is thus sanc tified and regulated and conformed to the verses of the Royal Psalmist: "I arose at midnight to give praise to Thee" (Matins), "Seven times a day have I given praise to Thee"1 (Lauds and the remaining hours). Each of the above divisions of the Divine Office is called, in liturgical language, an hour, conforming to the Roman and Jewish third, sixth, and ninth hour, etc. It is from this division of the day that the names are given to the various groups of prayers or hours recited daily by the priest when he reads his breviary. It is from the same source that has come the name of the service known to the laity as Sunday Vespers, and which constitutes only a portion of the Divine Office for that day. -

Poverty, Charity and the Papacy in The

TRICLINIUM PAUPERUM: POVERTY, CHARITY AND THE PAPACY IN THE TIME OF GREGORY THE GREAT AN ABSTRACT SUBMITTED ON THE FIFTEENTH DAY OF MARCH, 2013 TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOL OF LIBERAL ARTS OF TULANE UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ___________________________ Miles Doleac APPROVED: ________________________ Dennis P. Kehoe, Ph.D. Co-Director ________________________ F. Thomas Luongo, Ph.D. Co-Director ________________________ Thomas D. Frazel, Ph.D AN ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the role of Gregory I (r. 590-604 CE) in developing permanent ecclesiastical institutions under the authority of the Bishop of Rome to feed and serve the poor and the socio-political world in which he did so. Gregory’s work was part culmination of pre-existing practice, part innovation. I contend that Gregory transformed fading, ancient institutions and ideas—the Imperial annona, the monastic soup kitchen-hospice or xenodochium, Christianity’s “collection for the saints,” Christian caritas more generally and Greco-Roman euergetism—into something distinctly ecclesiastical, indeed “papal.” Although Gregory has long been closely associated with charity, few have attempted to unpack in any systematic way what Gregorian charity might have looked like in practical application and what impact it had on the Roman Church and the Roman people. I believe that we can see the contours of Gregory’s initiatives at work and, at least, the faint framework of an organized system of ecclesiastical charity that would emerge in clearer relief in the eighth and ninth centuries under Hadrian I (r. 772-795) and Leo III (r. -

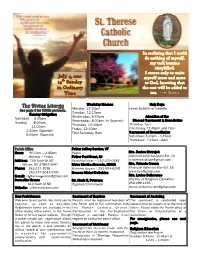

The Divine Liturgy Monday, 12:10Pm Check Bulletin Or Website See Page 3 for COVID Protocols

In realizing that I could do nothing of myself, my task became simplified. I strove only to unite July 4, 2021 myself more and more th 14 Sunday to God, knowing that in Ordinary the rest will be added to Time me. —St. Thérèse Weekday Masses Holy Days The Divine Liturgy Monday, 12:10pm check bulletin or website See page 3 for COVID protocols. Tuesday, 12:10pm Sunday Obligation Wednesday, 8:30am Adoration of the Saturday: 5:00pm Wednesday, 8:00pm (in Spanish) Blessed Sacrament & Benediction Sunday: 8:30am Thursday, 12:10pm Thursday, 7pm 11:00am Friday, 12:10pm First Friday,12:45pm and 7pm 1:30pm (Spanish) First Saturday, 9am Sacrament of Reconciliation 5:00pm (Spanish) Saturdays: 4:00pm - 4:45pm Thursdays: 7:15pm —8pm Parish Office Father Jeffrey Bowker, VF Hours: 9:00am — 2:45pm Pastor Mrs. Barbra Matrejek Monday — Friday Father Paul Brant, SJ Administrative Assistant-Ext. 10 Address: 700 Nash St NE Parochial Vicar — 252-229-0584 [email protected] Wilson, NC 27893-3047 Sister Martha Alvarado, HSMG Mrs. Yolanda Craven Phone: 252-237-3019 Ministerio Hispano -- 252-505-6258 Financial Administrator-Ext. 16 252-237-2042 (FAX) Deacon Michel DuSablon [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Mrs. Louise Bellavance Carmelite House: Mr. Mark N. Peterson Director of Religious Education 610 Nash St NE Organist/Choirmaster 252-299-1195 Website: sttheresewilson.com [email protected] New Parishioners Sacrament of Baptism Sacrament of Anointing Welcome to our parish. We invite you to Parents must be registered members of The sacrament is celebrated upon register, as soon as possible. -

The Rites of Holy Week

THE RITES OF HOLY WEEK • CEREMONIES • PREPARATIONS • MUSIC • COMMENTARY By FREDERICK R. McMANUS Priest of the Archdiocese of Boston 1956 SAINT ANTHONY GUILD PRESS PATERSON, NEW JERSEY Copyright, 1956, by Frederick R. McManus Nihil obstat ALFRED R. JULIEN, J.C. D. Censor Lib1·or111n Imprimatur t RICHARD J. CUSHING A1·chbishop of Boston Boston, February 16, 1956 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA INTRODUCTION ANCTITY is the purpose of the "new Holy Week." The news S accounts have been concerned with the radical changes, the upset of traditional practices, and the technical details of the re stored Holy Week services, but the real issue in the reform is the development of true holiness in the members of Christ's Church. This is the expectation of Pope Pius XII, as expressed personally by him. It is insisted upon repeatedly in the official language of the new laws - the goal is simple: that the faithful may take part in the most sacred week of the year "more easily, more devoutly, and more fruitfully." Certainly the changes now commanded ,by the Apostolic See are extraordinary, particularly since they come after nearly four centuries of little liturgical development. This is especially true of the different times set for the principal services. On Holy Thursday the solemn evening Mass now becomes a clearer and more evident memorial of the Last Supper of the Lord on the night before He suffered. On Good Friday, when Holy Mass is not offered, the liturgical service is placed at three o'clock in the afternoon, or later, since three o'clock is the "ninth hour" of the Gospel accounts of our Lord's Crucifixion. -

Emmanuel D'alzon

Gaétan Bernoville EMMANUEL D’ALZON 1810-1880 A Champion of the XIXth Century Catholic Renaissance in France Translated by Claire Quintal, docteur de l’Université de Paris, and Alexis Babineau, A.A. Bayard, Inc. For additional information about the Assumptionists contact Fr. Peter Precourt at (508) 767-7520 or visit the website: www.assumptionists.org © Copyright 2003 Bayard, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission of the publisher. Write to the Permissions Editor. ISBN: 1-58595-296-6 Printed in Canada Contents Contents Preface ................................................................................................. 5 Foreword .............................................................................................. 7 Historical Introduction ......................................................................... 13 I. The Child and the Student (1810-1830) .................................. 27 II. From Lavagnac to the Seminary of Montpellier and on to Rome (1830-1833).................................................................... 43 III. The Years in Rome (1833-1835) ............................................... 61 IV. The Vicar-General (1835-1844) ................................................ 81 V. Foundation of the Congregation of the Assumption (1844-1851) .............................................................................. 99 VI. The Great Trial in the Heat of Action (1851-1857) .................. 121 VII. From the Defense -

Saint Patrick Parish ‘A Faith Community Since 1870‘ 1 Cross Street Whitinsville, MA 01588

Saint Patrick Parish ‘A Faith Community since 1870‘ 1 Cross Street Whitinsville, MA 01588 MASS SCHEDULE Office Hours: Monday-Friday 9:00 AM - 4:00 PM Saturday: 4:30 PM Sunday 8:00 AM, 10:00 AM, 5:00 PM Rectory Phone: 508-234-5656 Monday– Wednesday 8:30 AM Rectory Fax: 508-234-6845 Religious Ed. Phone: 508-234-3511 Sacrament of Reconciliation: Parish Website: www.mystpatricks.com Confessions are offered every Saturday from 3:30 - 4:00 PM in the Church or by calling the Find us on Facebook at Parish Office for an appointment. St Patricks Parish Whitinsville St. Patrick Church, Whitinsville MA October 16, 2016 Twenty-Ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time Rev. Tomasz Borkowski: Deacon Patrick Stewart: Deacon Chris Finan: Deacon Pastor Deacon [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mrs. Christina Pichette: Mrs. Shelly Mombourquette: Pastoral Associate to Youth Ministry Administrative Assistant [email protected] [email protected] Mrs. Maryanne Swartz: Mrs. Mary Contino: Wedding Coordinator Coordinator of Children’s Ministries [email protected] [email protected] Mrs. Jackie Trottier: Operations Manager Mr. Jack Jackson: Cemetery Superintendent: [email protected] [email protected] Ms. Jeanne LeBlanc: Ministry Scheduler Mrs. Marylin Arrigan: Staff Support, Bulletin [email protected] [email protected] RELIGIOUS EDUCATION SCHEDULE OUR LADY OF THE VALLEY REGIONAL SCHOOL Pre school Sunday 10:00 AM - 11:00 AM 71 Mendon Street, Uxbridge, MA 01569 Kindergarten Sunday 10:00 AM - 11:00 AM 508-278-5851 First Grade Sunday 10:00 AM - 11:00 AM www.ourladyofthevalleyregional.com Grades 2 & 3 Sunday 11:20 AM - 12:20 PM Grades 4 & 5 Sunday 8:50 AM - 9:50 AM Free Breakfast every Saturday from 8-10 Children are to attend the 10:00 am Mass and take part AM for those in need. -

U.S. Catholic Mission Handbook 2006

U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION HANDBOOK 2006 Mission Inventory 2004 – 2005 Tables, Charts and Graphs Resources Published by the U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION 3029 Fourth St., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202 – 884 – 9764 Fax: 202 – 884 – 9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION HANDBOOK 2006 Mission Inventory 2004 – 2005 Tables, Charts and Graphs Resources ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Published by the U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION 3029 Fourth St., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202 – 884 – 9764 Fax: 202 – 884 – 9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org Additional copies may be ordered from USCMA. USCMA 3029 Fourth Street., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202-884-9764 Fax: 202-884-9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org COST: $4.00 per copy domestic $6.00 per copy overseas All payments should be prepaid in U.S. dollars. Copyright © 2006 by the United States Catholic Mission Association, 3029 Fourth St, NE, Washington, DC 20017-1102. 202-884-9764. [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: THE UNITED STATES CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION (USCMA)Purpose, Goals, Activities .................................................................................iv Board of Directors, USCMA Staff................................................................................................... v Past Presidents, Past Executive Directors, History ..........................................................................vi Part II: The U.S. -

The Autobiography of St. Anthony Mary Claret

Saint Anthony Mary Claret AUTOBIOGRAPHY Edited by JOSÉ MARIA VIÑAS, CMF Director Studium Claretianum Rome Forward by ALFRED ESPOSITO, CMF Claretian Publications Chicago, 1976 FOREWORD The General Prefecture for Religious Life has for some time wanted to bring out a pocket edition of the Autobiography of St. Anthony Mary Claret to enable all Claretians to enjoy the benefit of personal contact with the most authentic source of our charism and spirit. Without discounting the value of consulting other editions, it was felt there was a real need to make this basic text fully available to all Claretians. The need seemed all the more pressing in view of the assessment of the General Chapter of 1973: "Although, on the one hand, the essential elements and rationale of our charism are sufficiently explicit and well defined in the declarations 'On the Charism of our Founder' and 'On the Spiritual Heritage of the Congregation' (1967), on the other hand, they do not seem to have been sufficiently assimilated personally or communitarily, or fully integrated into our life" (cf. RL, 7, a and b). Our Claretian family's inner need to become vitally aware of its own charism is a matter that concerns the whole Church. Pope Paul's motu proprio "Ecclesiae Sanctae" prescribes that "for the betterment of the Church itself, religious institutes should strive to achieve an authentic understanding of their original spirit, so that adhering to it faithfully in their decisions for adaptation, religious life may be purified of elements that are foreign to it and freed from whatever is outdated" (II, 16, 3). -

Claretian Vocations

Who are the Claretians? We are a missionary community impelled by the love of Christ and in the spirit of our founder Claretian Saint Anthony Claret to: Explore Possibilities • Address the most urgent human needs Learn more about the Claretians by Vocations in the most effective manner joining us for a weekend retreat. Make Retreat in Chicago • Strive through every means to reflect connections and find ways to fulfill God’s love, especially to the poor your deep desire to make a difference. www.claretianvocations.org • Work collaboratively in decision- making • Accompany people through difficult transitions Claretian Vocation Office 205 West Monroe Street • Pursue spiritual growth in and through Chicago, Illinois 60606 social action Phone: (312) 236-7846 E-mail: [email protected] • Look to Mary, the Mother of Jesus, www.claretianvocations.org with special devotion and inspiration • Serve life in many more ways ... through parishes, community development, spiritual direction, youth ministry, and foreign missions March 14-16, 2008 Application and Let the Spirit move you Registration Send in this form or sign up online at Claretian Vocation Retreat in Chicago www.claretianvocations.org Name March 14-16, 2008 Street Address City, State, Zip E-Mail Meet us and let us meet you. Phone (Day) Join us for our weekend retreat March 14-16, 2008, in Chicago. Phone (Evening) Age You will take part in small group discussions, prayer, and liturgy and have time for Please describe briefly your hopes for the retreat: private reflection. You will also hear the stories of Claretian priests, brothers, and seminarians who work in an array of ministries. -

Jesuits and Eucharistic Concelebration

JesuitsJesuits and Eucharistic Concelebration James J. Conn, S.J.S.J. Jesuits,Jesuits, the Ministerial PPriesthood,riesthood, anandd EucharisticEucharistic CConcelebrationoncelebration JohnJohn F. Baldovin,Baldovin, S.J.S.J. 51/151/1 SPRING 2019 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits is a publication of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States. The Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality is composed of Jesuits appointed from their provinces. The seminar identifies and studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially US and Canadian Jesuits, and gath- ers current scholarly studies pertaining to the history and ministries of Jesuits throughout the world. It then disseminates the results through this journal. The opinions expressed in Studies are those of the individual authors. The subjects treated in Studies may be of interest also to Jesuits of other regions and to other religious, clergy, and laity. All who find this journal helpful are welcome to access previous issues at: [email protected]/jesuits. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR Note: Parentheses designate year of entry as a seminar member. Casey C. Beaumier, SJ, is director of the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. (2016) Brian B. Frain, SJ, is Assistant Professor of Education and Director of the St. Thomas More Center for the Study of Catholic Thought and Culture at Rock- hurst University in Kansas City, Missouri. (2018) Barton T. Geger, SJ, is chair of the seminar and editor of Studies; he is a research scholar at the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies and assistant professor of the practice at the School of Theology and Ministry at Boston College.