Front Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lincoln, Olmsted, and Yosemite: Time for a Closer Look

Lincoln, Olmsted, and Yosemite: Time for a Closer Look This year is the 150th anniversary of the Yosemite Grant and the act of Congress that set aside Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove for “public use, resort, and rec- reation … inalienable for all time.” This “grant” of federal lands transferred Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove to the state of California, yet the 1864 Yosemite Act represents the first significant reservation of public land by the Congress of the United States—to be pre- served in perpetuity for the benefit of the entire nation. As Joseph Sax affirms, “The national parks were born at that moment.”1 In 1890, Congress incorporated Yosemite State Park into a much larger Yosemite National Park. The Yosemite Conservancy is marking the 150th anniversary of the Yosemite Grant by releasing a new publication, Seed of the Future: Yosemite and the Evolution of the Nation al Park Idea, authored by the writer and filmmaker Dayton Duncan.2 The handsomely de- signed and generously illustrated book revisits the Yosemite Grant and the “evolution of the national park idea” and should attract a wide readership. This message is important, as the national significance of the Yosemite story has been obscured by time, incomplete documen- tation, and often-contradictory interpretations. A clearer understanding of the people and events surrounding the Yosemite Grant, in such a popular format, is particularly timely, not only for the celebration of Yosemite’s sesquicentennial, but also for the approaching 100th anniversary of the National Park Service (NPS) in 2016. It should be pointed out that Duncan is not the first recognize the significance of the Yosemite Grant. -

H. Doc. 108-222

THIRTY-NINTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1865, TO MARCH 3, 1867 FIRST SESSION—December 4, 1865, to July 28, 1866 SECOND SESSION—December 3, 1866, to March 3, 1867 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1865, to March 11, 1865 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—ANDREW JOHNSON, 1 of Tennessee PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—LAFAYETTE S. FOSTER, 2 of Connecticut; BENJAMIN F. WADE, 3 of Ohio SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—JOHN W. FORNEY, of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—GEORGE T. BROWN, of Illinois SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—SCHUYLER COLFAX, 4 of Indiana CLERK OF THE HOUSE—EDWARD MCPHERSON, 5 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—NATHANIEL G. ORDWAY, of New Hampshire DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—IRA GOODNOW, of Vermont POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—JOSIAH GIVEN ALABAMA James Dixon, Hartford GEORGIA SENATORS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES Vacant Vacant Henry C. Deming, Hartford REPRESENTATIVES 6 Samuel L. Warner, Middletown REPRESENTATIVES Vacant Augustus Brandegee, New London Vacant John H. Hubbard, Litchfield ARKANSAS ILLINOIS SENATORS SENATORS Vacant DELAWARE Lyman Trumbull, Chicago Richard Yates, Jacksonville REPRESENTATIVES SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES Vacant Willard Saulsbury, Georgetown George R. Riddle, Wilmington John Wentworth, Chicago CALIFORNIA John F. Farnsworth, St. Charles SENATORS REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE Elihu B. Washburne, Galena James A. McDougall, San Francisco John A. Nicholson, Dover Abner C. Harding, Monmouth John Conness, Sacramento Ebon C. Ingersoll, Peoria Burton C. Cook, Ottawa REPRESENTATIVES FLORIDA Henry P. H. Bromwell, Charleston Donald C. McRuer, San Francisco Shelby M. Cullom, Springfield William Higby, Calaveras SENATORS Lewis W. Ross, Lewistown John Bidwell, Chico Vacant 7 Anthony Thornton, Shelbyville Vacant 8 Samuel S. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

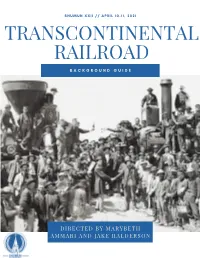

Transcontinental Railroad B a C K G R O U N D G U I D E

S H U M U N X X I I / / A P R I L 1 0 - 1 1 , 2 0 2 1 TRANSCONTINENTAL RAILROAD B A C K G R O U N D G U I D E D I R E C T E D B Y M A R Y B E T H A M M A R I A N D J A K E H A L D E R S O N 1 Letter from the Chair Esteemed Delegates, Welcome to SHUMUN! I am Kaitlyn Akroush, your chair for this committee. I am currently a second year student at Seton Hall University, double majoring in Diplomacy/International Relations and Philosophy. I am also a member of the Honors Program, the Seton Hall United Nations Association, and Turning Point USA. I have been a part of the Seton Hall United Nations Association since my freshman year and have truly enjoyed every bit of it. I have traveled and attended multiple conferences, participating in both General Assembly and Crisis Committees. This committee in particular is interesting as it will deal with the chaotic circumstances during the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad. A long road lies ahead, and there are many issues within the scope of this committee that need to be solved. Theodore Judah, American civil engineer and the central figure in the construction of the railroad has died, and the nation is in the midst of civil war. It is up to America’s remaining engineers to step up and unite the country, both figuratively and literally, all while maintaining positive relationships with Native Americans during the expansion West. -

Floral Ball, Centerville Hotel

SHASTA COURIER. The Duties of Democrats. Judge Landrum. Indian Troubles. CANDIDATES FOR OFFICE. FLORAL BALL, Since our connection with this paper, wc It is much to horegretted that in times of The Indians hare been very troublesome For Sopmlsor. AT THE OHIO GARDEN, in COtTHTY OFFICIAL PAPES have pursued a uniform coarse of urging great political excitement a disposition should' recently, the counties of Humboldt .and WILLIAM MAGEE. on Democrats the duty, at all times and under be exflibited to impeach the honesty and Trinity, as depredations of a very extensive Bj request, we announce the name of William SATURDAY MORNING, JULY 27, 1861. the all and of our men, on insufficient character bad been committed on settlers on Magee as a candidate for Supervisor for First a Grand circumstances, of giving a cordial standing public Shasta at the approach- THE UNDERSIGNED will give River Supervisor District, county, Garden, on the even- generous to their nominees—State grounds. Certain Black Republican jour- Eel and Hay Fork of Trinity. In view ing election. Floral Bail at the Ohio support iiigof UNION DEMOCRATIC TICKET. and County—in the coming election. We nals, and the San Francisco Bulletin in par- ofthese facts, it may be asked of what value ? Assemblyman. have also assumed the strongest Union ticular, have been very busy in this line of are the Reservations Hunger is the prime Friday, Augrnst 9th, and advocated the of late, and have earned a wide spread reputa- cause that impels the Indian to steal and THOMAS W. COBBEY. grounds, maintainance On which occasion he hope* to meet all his friends tion for vituperation and detraction of char- drive off the cattle of the settler, slaughter We arc authorized to announce the name of the Government of the United States against W. -

Statement of Vote to All Californians

PREFACE I am pleased to provide this Statement of Vote to all Californians. This document reports voter registration and participation results for the November 2, 2004 presidential election as well as prior elections dating back to 1910. The report contains the county-by-county totals of votes cast for the offices of President of the United States, United States Senator, United States Representative, State Senator (the odd–numbered districts), Member of the State Assembly, and for the statewide ballot measures. KEVIN SHELLEY Secretary of State TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................................................i TABLE OF CONTENTS .....................................................................................................................................................ii ABOUT THIS STATEMENT OF VOTE ...............................................................................................................................iii REGISTRATION AND PARTICIPATION − Voter Registration Statistics by County ..........................................................................................................v − Voter Participation Statistics by County........................................................................................................vii − Comparative Voter Registration and Participation in Statewide Elections -- 1910 through 2004..................ix INITIATIVE, REFERENDUM, AND POLITICAL -

Yosemite Guide

G 83 after a major snowfall. major a after Note: Service to stops 15, 16, 17, and 18 may stop stop may 18 and 17, 16, 15, stops to Service Note: Third Class Mail Class Third Postage and Fee Paid Fee and Postage US Department Interior of the December 17, 2008 - February 17, 2009 17, February - 2008 17, December Guide Yosemite Park National Yosemite America Your Experience US Department Interior of the Service Park National 577 PO Box CA 95389 Yosemite, Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Vol. 34, Issue No.1 Inside: 01 Welcome to Yosemite 05 Programs and Events 06 Services and Facilities 10 Special Feature: Lincoln & Yosemite Dec ‘08 - Feb ‘09 Yosemite Falls. Photo by Christine White Loberg Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park December 17, 2008 - February 17, 2009 Yosemite Guide Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Yosemite Guide December 17, 2008 - February 17, 2009 Welcome to Yosemite Keep this Guide with You to Get the Most Out of Your Trip to Yosemite National Park information on topics such as camping and hiking. Keep this guide with you as you make your way through the park. Pass it along to friends and family when you get home. Save it as a memento of your trip. This guide represents the collaborative energy of the National Park Service, The Yosemite Fund, DNC Parks & Resorts at Yosemite, Yosemite Association, The Ansel Adams Gallery, and Yosemite Institute—organizations dedicated to Yosemite and to making Illustration by Lawrence W. Duke your visit enjoyable and inspiring (see page 11). -

Image Credits

Preparing for the Oath Credits 1. Government Basics 2. Courts 3. The Presidency 4. Congress 5. Rights 6. Responsibilities 7. Voting 8. Establishing Independence 9. Writing the Constitution 10. A Growing Nation 11. The 1800s 12. The 1900s 13. Famous Citizens 14. Geography 15. Symbols & Holidays 1 of 134 Government Basics 2. What does the Constitution do? Americans singing the National Anthem, the Star-Spangled Banner. Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History. First page of the United States Constitution, written in 1787 and ratified in 1789. Courtesy of United States National Archives and Records Administration. The Continental Congress voting for independence, after 1796. Image by Edward Savage. Smithsonian Institution, National Portrait A citizen casts his ballot. Gallery. Courtesy of the Polling Place Photo Project. 1. What is the supreme law of the land? House of Representatives in session, between 1905-1945. Photograph by Harris & Ewing. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. First page of the United States Constitution, written in 1787 and ratified in 1789. 2 of 134 Courtesy of United States National Courtesy of the Supreme Court of the Archives and Records Administration. United States. Journals of the Supreme Court of the United States documenting trials and 1974 Courtroom drawing. verdicts. Drawing by Steve Petteway. Courtesy of Supreme Court of the United States. Courtesy of Supreme Court of the United States. Betty Friedan, president of the National Frieze of the Supreme Court of the United Organization of Women, leading a group States building, reading “Equal Justice of demonstrators outside a Under Law.” Congressional office in 1971 to support the Equal Rights Amendment. -

Corporate Public Relations of the First Transcontinental

When the Locomotive Puffs: Corporate Public Relations of the First Transcontinental Railroad Builders, 1863-69 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Leland K. Wood August 2009 © 2009 Leland K. Wood. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled When the Locomotive Puffs: Corporate Public Relations of the First Transcontinental Railroad Builders, 1863-69 by LELAND K. WOOD has been approved for the E. W. Scripps School of Journalism and the Scripps College of Communication by Patrick S. Washburn Professor of Journalism Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii Abstract WOOD, LELAND K., Ph.D., August 2009, Journalism When the Locomotive Puffs: Corporate Public Relations of the First Transcontinental Railroad Builders, 1863-69 (246 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Patrick S. Washburn The dissertation documents public-relations practices of officers and managers in two companies: the Central Pacific Railroad with offices in Sacramento, California, and the Union Pacific Railroad with offices in New York City. It asserts that sophisticated and systematic corporate public relations were practiced during the construction of the first transcontinental railroad, fifty years before historians generally place the beginning of such practice. Documentation of the transcontinental railroad practices was gathered utilizing existing historical presentations and a review of four archives containing correspondence and documents from the period. Those leading the two enterprises were compelled to practice public relations in order to raise $125 million needed to construct the 1,776-mile-long railroad by obtaining and keeping federal loan guarantees and by establishing and maintaining an image attractive to potential bond buyers. -

A Political Manual for 1869

A POLITICAL. ~IANUAL FOR 1869, I~CLUDING A CLASSIFIED SUMMARY OF THE IMPORTANT EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE,JUDICIAL, POLITICO-MILITARY GENERAL FACTS OF THE PERIOD. From July 15, 1868. to July 15, 1869. BY EDWARD McPHERSON, LL.D., CLERK OF TllB ROUS!: OF REPRESENTATIVES OF TU:B U!flTED STATES. WASHINGTON CITY : PHILP & SOLOMONS. 1869. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 186?, by EDWAR}) McPIIERSON, In the Clerk's Office of the District Conrt of the United Sto.tes for the District of Columbia. _.......,============================ • 9-ootype<il>J llihOILI, <l WITHEROW, Wa.aLingturi., O. C. PREFACE. This volume contains the same class of facts found in the :Manual for 1866, 1867, and 1868. .The record is continued from the date of the close of the Manual for 1868, to the present time. The votes in Congress during the struggle· which resulted in the passage of the Suffrage or XVth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, will disclose the contrariety of opinion which prevailed upon this point, and the mode in which an adjustment was reached; while the various votes upon it in the State Legislatures will show the present state of the question of Ratification. The a<Jditional legislation on Reconstruction, with the Executive and l\Iilitary action under it; the conflict on the Tenure-of-Office Act and the Public Credit Act; the votes upon the mode of payment of United States Bonds, Female Suffrage, l\Iinority Representation, Counting the Electoral Votes, &c.; the l\Iessage of the late President, and the Condemnatory Votes -

National Memorial

Part 2 Shaping the System President Theodore Roosevelt (left) and John Muir at Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park, ca. 1903. Before the National Park Service National Parks from agents of the Northern Pacific Railroad Company, whose pro- The national park idea—the concept of large-scale natural preserva- jected main line through Montana stood to benefit from a major tion for public enjoyment—has been credited to the artist George tourist destination in the vicinity. Catlin, best known for his paintings of American Indians. On a trip to Yosemite was cited as a precedent, but differences in the two situa- the Dakota region in 1832, he worried about the destructive effects of tions required different solutions. The primary access to Yellowstone America’s westward expansion on Indian civilization, wildlife, and was through Montana, and Montanans were among the leading park wilderness. They might be preserved, he wrote, “by some great pro- advocates. Most of Yellowstone lay in Wyoming, however, and nei- tecting policy of government . in a magnificent park....a nation’s ther Montana nor Wyoming was yet a state. So the park legislation, park, containing man and beast, in all the wild[ness] and freshness of introduced in December 1871 by Senate Public Lands Committee their nature’s beauty!” Chairman Samuel C. Pomeroy of Kansas, was written to leave Yel- Catlin’s vision of perpetuating indigenous cultures in this fashion lowstone in federal custody. was surely impractical, and his proposal had no immediate effect. The Yellowstone bill encountered some opposition from congress- Increasingly, however, romantic portrayals of nature by writers like men who questioned the propriety of such a large reservation. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 74-2014

THE REPUBLICAN PARTY IN CALIFORNIA, 1856-1868 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Stanley, Gerald, 1941- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 08:34:09 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288108 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material, it is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap.