Slavery, Liberty, and the Right to Contract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Law and Contemporary Forms of Slavery: an Economic and Social Rights-Based Approach A

Penn State International Law Review Volume 23 Article 15 Number 4 Penn State International Law Review 5-1-2005 International Law and Contemporary Forms of Slavery: An Economic and Social Rights-Based Approach A. Yasmine Rassam Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Recommended Citation Rassam, A. Yasmine (2005) "International Law and Contemporary Forms of Slavery: An Economic and Social Rights-Based Approach," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 23: No. 4, Article 15. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol23/iss4/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I International Law and Contemporary Forms of Slavery: An Economic and Social Rights-Based Approach A. Yasmine Rassam* I. Introduction The prohibition of slavery is non-derogable under comprehensive international and regional human rights treaties, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights'; the International Covenant on Civil and * J.S.D. Candidate, Columbia University School of Law. LL.M. 1998, Columbia University School of Law; J.D., magna cum laude, 1994, Indiana University, Bloomington; B.A. 1988, University of Virginia. I would like to thank the Columbia Law School for their financial support. I would also like to thank Mark Barenberg, Lori Damrosch, Alice Miller, and Peter Rosenblum for their comments and guidance on earlier drafts of this article. I am grateful for the editorial support of Clara Schlesinger. -

Chinese Privatization: Between Plan and Market

CHINESE PRIVATIZATION: BETWEEN PLAN AND MARKET LAN CAO* I INTRODUCTION Since 1978, when China adopted its open-door policy and allowed its economy to be exposed to the international market, it has adhered to what Deng Xiaoping called "socialism with Chinese characteristics."1 As a result, it has produced an economy with one of the most rapid growth rates in the world by steadfastly embarking on a developmental strategy of gradual, market-oriented measures while simultaneously remaining nominally socialistic. As I discuss in this article, this strategy of reformthe mere adoption of a market economy while retaining a socialist ownership baseshould similarly be characterized as "privatization with Chinese characteristics,"2 even though it departs markedly from the more orthodox strategy most commonly associated with the term "privatization," at least as that term has been conventionally understood in the context of emerging market or transitional economies. The Russian experience of privatization, for example, represents the more dominant and more favored approach to privatizationcertainly from the point of view of the West and its advisersand is characterized by immediate privatization of the state sector, including the swift and unequivocal transfer of assets from the publicly owned state enterprises to private hands. On the other hand, "privatization with Chinese characteristics" emphasizes not the immediate privatization of the state sector but rather the retention of the state sector with the Copyright © 2001 by Lan Cao This article is also available at http://www.law.duke.edu/journals/63LCPCao. * Professor of Law, College of William and Mary Marshall-Wythe School of Law. At the time the article was written, the author was Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School. -

Union Security and the Right to Work Laws: Is Coexistence Possible?

William & Mary Law Review Volume 2 (1959-1960) Issue 1 Article 3 October 1959 Union Security and the Right to Work Laws: Is Coexistence Possible? J. T. Cutler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons Repository Citation J. T. Cutler, Union Security and the Right to Work Laws: Is Coexistence Possible?, 2 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 16 (1959), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol2/iss1/3 Copyright c 1959 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr UNION SECURITY AND RIGHT-TO-WORK LAWS: IS CO-EXISTENCE POSSIBLE? J. T. CUTLER THE UNION STRUGGLE At the beginning of the 20th Century management was all powerful and with the decision in Adair v. United States1 it seemed as though Congress was helpless to regulate labor relations. The Supreme Court had held that the power to regulate commerce could not be applied to the labor field because of the conflict with fundamental rights secured by the Fifth Amendment. Moreover, an employer could require a person to agree not to join a union as a condition of his employment and any legislative interference with such an agreement would be an arbitrary and unjustifiable infringement of the liberty of contract. It was not until the first World War that the federal government successfully entered the field of industrial rela- tions with the creation by President Wilson of the War Labor Board. Upon being organized the Board adopted a policy for- bidding employer interference with the right of employees to organize and bargain collectively and employer discrimination against employees engaging in lawful union activities2 . -

Azimuth Corporation Employee Handbook

Azimuth Corporation Employee Handbook ABOUT THIS HANDBOOK/DISCLAIMER This Employee Handbook is designed to acquaint you with Azimuth Corporation and to provide employees with an overview of the policies, procedures and management practices affecting employment with our company. Unless otherwise stated, these policies and practices apply to all Azimuth employees as of the date of this Employee Handbook, and those that may begin after its effective date. This Employee Handbook outlines the programs developed by Azimuth for the benefit of its employees, and the employee's responsibility to Azimuth and its customers. Each employee should read, understand and comply with the provisions of this handbook. Please take the necessary time to read it. Please contact your Supervisor and/or the Human Resources Department if you require additional information. Neither this handbook nor any other verbal or written communication by a management representative is, nor should it be considered to be, an agreement, contract of employment, express or implied, or a promise of treatment in any particular manner in any given situation, nor does it confer any contractual rights whatsoever. This Employee Handbook does not constitute a contract of employment between Azimuth and its employees, whether expressed or implied. The handbook, nor any portion of it, does not preempt the doctrine of employment-at-will. Azimuth Corporation adheres to the policy of employment at will, which permits the Company or the employee to end the employment relationship at any time, for any reason, with or without cause or notice. Many matters covered by this handbook, such as benefit plan descriptions, are also described in separate Company documents. -

Front Matter

Graham_Presidents & Environment 4/17/15 3:32 PM Page vii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 The New Nation’s Public Lands: A First Century without a National Vision 3 2 Benjamin Harrison, Grover Cleveland, and William McKinley: The Idea of Preserving the Public Lands Finds Cautious Presidential Sponsors, 1891–1901 23 3 Theodore Roosevelt: The Conservation Crusade Welcomes a Presidential Leader, 1901–1909 37 4 William Taft, Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover: The Conservation Agenda, 1910s–1920s 59 5 Franklin D. Roosevelt: Conservation Foundations of New Deal Leadership, 1930s–1940s 114 6 Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, and John F. Kennedy: Growing and Polluting in Boom Times, 1940s–1950s 153 7 Lyndon Baines Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter: Environmentalism Arrives, 1960s–1970s 209 8 Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and Bill Clinton: Presidents Brown and Pale Green, 1980s–1990s 276 9 George W. Bush and Barack Obama: Wobbly Leaders, 2000– 328 10. Trying Again for Greener Presidents 358 Notes 367 Suggested Further Reading 391 Index 409 Graham_Presidents & Environment 4/17/15 3:32 PM Page viii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Graham_Presidents & Environment 4/17/15 3:32 PM Page ix © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for research assistance from UNC history graduate students Scott Phillips, Rob Shapard, Carla Hoffman, and Matthew Lubin, and from Kris Smemo and Dustin Walker at the University of California–Santa Bar- bara (history). -

Modern-Day Slavery & Human Rights

& HUMAN RIGHTS MODERN-DAY SLAVERY MODERN SLAVERY What do you think of when you think of slavery? For most of us, slavery is something we think of as a part of history rather than the present. The reality is that slavery still thrives in our world today. There are an estimated 21-30 million slaves in the world today. Today’s slaves are not bought and sold at public auctions; nor do their owners hold legal title to them. Yet they are just as surely trapped, controlled and brutalized as the slaves in our history books. What does slavery look like today? Slaves used to be a long-term economic investment, thus slaveholders had to balance the violence needed to control the slave against the risk of an injury that would reduce profits. Today, slaves are cheap and disposable. The sick, injured, elderly and unprofitable are dumped and easily replaced. The poor, uneducated, women, children and marginalized people who are trapped by poverty and powerlessness are easily forced and tricked into slavery. Definition of a slave: A person held against his or her will and controlled physically or psychologically by violence or its threat for the purpose of appropriating their labor. What types of slavery exist today? Bonded Labor Trafficking A person becomes bonded when their labor is demanded This involves the transport and/or trade of humans, usually as a means of repayment of a loan or money given in women and children, for economic gain and involving force advance. or deception. Often migrant women and girls are tricked and forced into domestic work or prostitution. -

Curtailing Inherited Wealth

Michigan Law Review Volume 89 Issue 1 1990 Curtailing Inherited Wealth Mark L. Ascher University of Arizona College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Law and Society Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Taxation-Federal Estate and Gift Commons Recommended Citation Mark L. Ascher, Curtailing Inherited Wealth, 89 MICH. L. REV. 69 (1990). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol89/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CURTAILING INHERITED WEALTH Mark L. Ascher* INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • . • • . • • • • . • • • 70 I. INHERITANCE IN PRINCIPLE........................... 76 A. Inheritance as a Natural Right..................... 76 B. The Positivistic Conception of Inheritance . 77 C. Why the Positivistic Conception Prevailed . 78 D. Inheritance - Property or Garbage?................ 81 E. Constitutional Concerns . 84 II. INHERITANCE AS A MATIER OF POLICY •• • . •••••.. •••• 86 A. Society's Stake in Accumulated Wealth . 86 B. Arguments in Favor of Curtailing Inheritance . 87 1. Leveling the Playing Field . 87 2. Deficit Reduction in a Painless and Appropriate Fashion........................................ 91 3. Protecting Elective Representative Government . 93 4. Increasing Privatization in the Care of the Disabled and the Elderly . 96 5. Expanding Public Ownership of National and International Treasures . 98 6. _Increasing Lifetime Charitable Giving . 98 7. Neutralizing the Co"osive Effects of Wealth..... 99 C. Arguments Against Curtailing Inheritance. -

The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, As Amended

The Fair LaboR Standards Act Of 1938, As Amended U.S. DepaRtment of LaboR Wage and Hour Division WH Publication 1318 Revised May 2011 material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced fully or partially, without permission of the Federal Government. Source credit is requested but not required. Permission is required only to reproduce any copyrighted material contained herein. This material may be contained in an alternative Format (Large Print, Braille, or Diskette), upon request by calling: (202) 693-0675. Toll-free help line: 1-866-187-9243 (1-866-4-USWAGE) TTY TDD* phone: 1-877-889-5627 *Telecommunications Device for the Deaf. Internet: www.wagehour.dol.gov The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, as amended 29 U.S.C. 201, et seq. To Provide for the establishment of fair labor standards in emPloyments in and affecting interstate commerce, and for other Purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That this Act may be cited as the “Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938”. § 201. Short title This chapter may be cited as the “Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938”. § 202. Congressional finding and declaration of Policy (a) The Congress finds that the existence, in industries engaged in commerce or in the Production of goods for commerce, of labor conditions detrimental to the maintenance of the minimum standard of living necessary for health, efficiency, and general well-being of workers (1) causes commerce and the channels and instrumentalities of commerce to be used to sPread and Perpetuate such labor conditions among the workers of the several States; (2) burdens commerce and the free flow of goods in commerce; (3) constitutes an unfair method of competition in commerce; (4) leads to labor disputes burdening and obstructing commerce and the free flow of goods in commerce; and (5) interferes with the orderly and fair marketing of goods in commerce. -

Shareholder Capitalism a System in Crisis New Economics Foundation Shareholder Capitalism

SHAREHOLDER CAPITALISM A SYSTEM IN CRISIS NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATION SHAREHOLDER CAPITALISM SUMMARY Our current, highly financialised, form of shareholder capitalism is not Shareholder capitalism just failing to provide new capital for – a system driven by investment, it is actively undermining the ability of listed companies to the interests of reinvest their own profits. The stock shareholder-backed market has become a vehicle for and market-fixated extracting value from companies, not companies – is broken. for injecting it. No wonder that Andy Haldane, Chief Economist of the Bank of England, recently suggested that shareholder capitalism is ‘eating itself.’1 Corporate governance has become dominated by the need to maximise short-term shareholder returns. At the same time, financial markets have grown more complex, highly intermediated, and similarly short- termist, with shares increasingly seen as paper assets to be traded rather than long-term investments in sound businesses. This kind of trading is a zero-sum game with no new wealth, let alone social value, created. For one person to win, another must lose – and increasingly, the only real winners appear to be the army of financial intermediaries who control and perpetuate the merry-go- round. There is nothing natural or inevitable about the shareholder-owned corporation as it currently exists. Like all economic institutions, it is a product of political and economic choices which can and should be remade if they no longer serve our economy, society, or environment. Here’s the impact -

MARGARET GARNER a New American Opera in Two Acts

Richard Danielpour MARGARET GARNER A New American Opera in Two Acts Libretto by Toni Morrison Based on a true story First performance: Detroit Opera House, May 7, 2005 Opera Carolina performances: April 20, 22 & 23, 2006 North Carolina Blumenthal Performing Arts Center Stefan Lano, conductor Cynthia Stokes, stage director The Opera Carolina Chorus The Charlotte Contemporary Ensemble The Charlotte Symphony Orchestra The Characters Cast Margaret Garner, mezzo slave on the Gaines plantation Denyce Graves Robert Garner, bass baritone her husband Eric Greene Edward Gaines, baritone owner of the plantation Michael Mayes Cilla, soprano Margaret’s mother Angela Renee Simpson Casey, tenor foreman on the Gaines plantation Mark Pannuccio Caroline, soprano Edward Gaines’ daughter Inna Dukach George, baritone her fiancée Jonathan Boyd Auctioneer, tenor Dale Bryant First Judge , tenor Dale Bryant Second Judge, baritone Daniel Boye Third Judge, baritone Jeff Monette Slaves on the Gaines plantation, Townspeople The opera takes place in Kentucky and Ohio Between 1856 and 1861 1 MARGARET GARNER Act I, scene i: SLAVE CHORUS Kentucky, April 1856. …NO, NO. NO, NO MORE! NO, NO, NO! The opera begins in total darkness, without any sense (basses) PLEASE GOD, NO MORE! of location or time period. Out of the blackness, a large group of slaves gradually becomes visible. They are huddled together on an elevated platform in the MARGARET center of the stage. UNDER MY HEAD... CHORUS: “No More!” SLAVE CHORUS THE SLAVES (Slave Chorus, Margaret, Cilla, and Robert) … NO, NO, NO MORE! NO, NO MORE. NO, NO MORE. NO, NO, NO! NO MORE, NOT MORE. (basses) DEAR GOD, NO MORE! PLEASE, GOD, NO MORE. -

Privatization of Public Social Services a Background Paper Demetra Smith Nightingale, Nancy M

Privatization of Public Social Services A Background Paper Demetra Smith Nightingale, Nancy M. Pindus This paper was prepared at the Urban Institute for U.S. Department of Labor, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Document date: October 15, 1997 Policy, under DOL Contract No. J-9-M-5-0048, #15. Released online: October 15, 1997 Opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the positions of DOL, the Urban Institute or its sponsors. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Urban Institute, its board, its sponsors, or other authors in the series 1. Introduction The purposes of the paper are to provide a general overview of the extent of privatization of public services in the areas of social services, welfare, and employment; rationales for privatizing service delivery, and evidence of effectiveness or problems. Examples are included to highlight specific types of privatization and actual operational experience. The paper is not intended to be a comprehensive treatment of the overall subject of privatization, but rather a brief review of issues and experiences specifically related to the delivery of employment and training, welfare, and social services. The key points that are drawn from a review of the literature are: There is no single definition of privatization. Privatization covers a broad range of methods and models, including contracting out for services, voucher programs, and even the sale of public assets to the private sector. But for the purposes of this paper, privatization refers to the provision of publicly-funded services and activities by non-governmental entities. -

RIVERFRONT CIRCULATING MATERIALS (Can Be Checked Out)

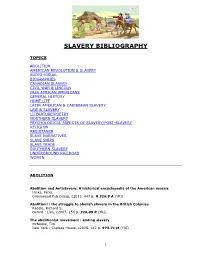

SLAVERY BIBLIOGRAPHY TOPICS ABOLITION AMERICAN REVOLUTION & SLAVERY AUDIO-VISUAL BIOGRAPHIES CANADIAN SLAVERY CIVIL WAR & LINCOLN FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS GENERAL HISTORY HOME LIFE LATIN AMERICAN & CARIBBEAN SLAVERY LAW & SLAVERY LITERATURE/POETRY NORTHERN SLAVERY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SLAVERY/POST-SLAVERY RELIGION RESISTANCE SLAVE NARRATIVES SLAVE SHIPS SLAVE TRADE SOUTHERN SLAVERY UNDERGROUND RAILROAD WOMEN ABOLITION Abolition and Antislavery: A historical encyclopedia of the American mosaic Hinks, Peter. Greenwood Pub Group, c2015. 447 p. R 326.8 A (YRI) Abolition! : the struggle to abolish slavery in the British Colonies Reddie, Richard S. Oxford : Lion, c2007. 254 p. 326.09 R (YRI) The abolitionist movement : ending slavery McNeese, Tim. New York : Chelsea House, c2008. 142 p. 973.71 M (YRI) 1 The abolitionist legacy: from Reconstruction to the NAACP McPherson, James M. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, c1975. 438 p. 322.44 M (YRI) All on fire : William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery Mayer, Henry, 1941- New York : St. Martin's Press, c1998. 707 p. B GARRISON (YWI) Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the heroic campaign to end slavery Metaxas, Eric New York, NY : Harper, c2007. 281p. B WILBERFORCE (YRI, YWI) American to the backbone : the life of James W.C. Pennington, the fugitive slave who became one of the first black abolitionists Webber, Christopher. New York : Pegasus Books, c2011. 493 p. B PENNINGTON (YRI) The Amistad slave revolt and American abolition. Zeinert, Karen. North Haven, CT : Linnet Books, c1997. 101p. 326.09 Z (YRI, YWI) Angelina Grimke : voice of abolition. Todras, Ellen H., 1947- North Haven, Conn. : Linnet Books, c1999. 178p. YA B GRIMKE (YWI) The antislavery movement Rogers, James T.