Session 1: Leach Birdsong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Peacock Cult in Asia

The Peacock Cult in Asia By P. T h a n k a p p a n N a ir Contents Introduction ( 1 ) Origin of the first Peacock (2) Grand Moghul of the Bird Kingdom (3) How did the Peacock get hundred eye-designs (4) Peacock meat~a table delicacy (5) Peacock in Sculptures & Numismatics (6) Peacock’s place in history (7) Peacock in Sanskrit literature (8) Peacock in Aesthetics & Fine Art (9) Peacock’s place in Indian Folklore (10) Peacock worship in India (11) Peacock worship in Persia & other lands Conclusion Introduction Doubts were entertained about India’s wisdom when Peacock was adopted as her National Bird. There is no difference of opinion among scholars that the original habitat of the peacock is India,or more pre cisely Southern India. We have the authority of the Bible* to show that the peacock was one of the Commodities5 that India exported to the Holy Land in ancient times. This splendid bird had reached Athens by 450 B.C. and had been kept in the island of Samos earlier still. The peacock bridged the cultural gap between the Aryans who were * I Kings 10:22 For the king had at sea a navy of Thar,-shish with the navy of Hiram: once in three years came the navy of Thar’-shish bringing gold, and silver,ivory, and apes,and peacocks. II Chronicles 9: 21 For the King’s ships went to Tarshish with the servants of Hu,-ram: every three years once came the ships of Tarshish bringing gold, and silver,ivory,and apes,and peacocks. -

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor RESEARCH IN MEDIEVAL CULTURE Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Medieval Institute Publications is a program of The Medieval Institute, College of Arts and Sciences Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor MEDIEVAL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS Western Michigan University Kalamazoo Copyright © 2015 by the Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taylor, Robert A. (Robert Allen), 1937- Bibliographical guide to the study of the troubadours and old Occitan literature / Robert A. Taylor. pages cm Includes index. Summary: "This volume provides offers an annotated listing of over two thousand recent books and articles that treat all categories of Occitan literature from the earli- est enigmatic texts to the works of Jordi de Sant Jordi, an Occitano-Catalan poet who died young in 1424. The works chosen for inclusion are intended to provide a rational introduction to the many thousands of studies that have appeared over the last thirty-five years. The listings provide descriptive comments about each contri- bution, with occasional remarks on striking or controversial content and numerous cross-references to identify complementary studies or differing opinions" -- Pro- vided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-58044-207-7 (Paperback : alk. paper) 1. Provençal literature--Bibliography. 2. Occitan literature--Bibliography. 3. Troubadours--Bibliography. 4. Civilization, Medieval, in literature--Bibliography. -

TRECENTO FRAGMENTS M Ichael Scott Cuthbert to the Department Of

T R E C E N T O F R A G M E N T S A N D P O L Y P H O N Y B E Y O N D T H E C O D E X a thesis presented by M ichael Scott Cuthbert t the Depart!ent " M#si$ in partia% "#%"i%%!ent " the re&#ire!ents " r the de'ree " D $t r " Phi% s phy in the s#b(e$t " M#si$ H ar)ard * ni)ersity Ca!brid'e+ Massa$h#setts A#'#st ,--. / ,--.+ Mi$hae% S$ tt C#thbert A%% ri'hts reser)ed0 Pr "0 Th !as F rrest 1 e%%y+ advisor Mi$hae% S$ tt C#thbert Tre$ent Fra'!ents and P %yph ny Bey nd the C de2 Abstract This thesis see3s t #nderstand h 4 !#si$ s #nded and "#n$ti ned in the 5ta%ian tre6 $ent based n an e2a!inati n " a%% the s#r)i)in' s #r$es+ rather than n%y the ! st $ !6 p%ete0 A !a( rity " s#r)i)in' s #r$es " 5ta%ian p %yph ni$ !#si$ "r ! the peri d 788-9 7:,- are "ra'!ents; ! st+ the re!nants " % st !an#s$ripts0 Despite their n#!eri$a% d !i6 nan$e+ !#si$ s$h %arship has )ie4 ed these s #r$es as se$ ndary <and "ten ne'%e$ted the! a%t 'ether= " $#sin' instead n the "e4 %ar'e+ retr spe$ti)e+ and pred !inant%y se$#%ar $ di6 $es 4 hi$h !ain%y ri'inated in the F% rentine rbit0 C nne$ti ns a! n' !an#s$ripts ha)e been in$ !p%ete%y e2p% red in the %iterat#re+ and the !issi n is a$#te 4 here re%ati nships a! n' "ra'!ents and a! n' ther s!a%% $ %%e$ti ns " p %yph ny are $ n$erned0 These s!a%% $ %%e$ti ns )ary in their $ nstr#$ti n and $ ntents>s !e are n t rea%%y "ra'!ents at a%%+ b#t sin'%e p %yph ni$ 4 r3s in %it#r'i$a% and ther !an#s$ripts0 5ndi)id#6 a%%y and thr #'h their )ery n#!bers+ they present a 4 ider )ie4 " 5ta%ian !#si$a% %i"e in the " #rteenth $ent#ry than $ #%d be 'ained "r ! e)en the ! st $are"#% s$r#tiny " the inta$t !an#s$ripts0 E2a!inin' the "ra'!ents e!b %dens #s t as3 &#esti ns ab #t musical style, popularity, scribal practice, and manuscript transmission: questions best answered through a study of many different sources rather than the intense scrutiny of a few large sources. -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

The Troubadours

The Troubadours H.J. Chaytor The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Troubadours, by H.J. Chaytor This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Troubadours Author: H.J. Chaytor Release Date: May 27, 2004 [EBook #12456] Language: English and French Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TROUBADOURS *** Produced by Ted Garvin, Renald Levesque and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. THE TROUBADOURS BY REV. H.J. CHAYTOR, M.A. AUTHOR OF "THE TROUBADOURS OF DANTE" ETC. Cambridge: at the University Press 1912 _With the exception of the coat of arms at the foot, the design on the title page is a reproduction of one used by the earliest known Cambridge printer, John Siberch, 1521_ PREFACE This book, it is hoped, may serve as an introduction to the literature of the Troubadours for readers who have no detailed or scientific knowledge of the subject. I have, therefore, chosen for treatment the Troubadours who are most famous or who display characteristics useful for the purpose of this book. Students who desire to pursue the subject will find further help in the works mentioned in the bibliography. The latter does not profess to be exhaustive, but I hope nothing of real importance has been omitted. H.J. CHAYTOR. THE COLLEGE, PLYMOUTH, March 1912. CONTENTS PREFACE CHAP. I. INTRODUCTORY II. -

![Bernart De Ventadorn [De Ventador, Del Ventadorn, De Ventedorn] (B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6126/bernart-de-ventadorn-de-ventador-del-ventadorn-de-ventedorn-b-1026126.webp)

Bernart De Ventadorn [De Ventador, Del Ventadorn, De Ventedorn] (B

Bernart de Ventadorn [de Ventador, del Ventadorn, de Ventedorn] (b Ventadorn, ?c1130–40; d ?Dordogne, c1190–1200). Troubadour. He is widely regarded today as perhaps the finest of the troubadour poets and probably the most important musically. His vida, which contains many purely conventional elements, states that he was born in the castle of Ventadorn in the province of Limousin, and was in the service of the Viscount of Ventadorn. In Lo temps vai e ven e vire (PC 70.30, which survives without music), he mentioned ‘the school of Eble’ (‘l'escola n'Eblo’) – apparently a reference to Eble II, Viscount of Ventadorn from 1106 to some time after 1147. It is uncertain, however, whether this reference is to Eble II or his son and successor Eble III; both were known as patrons of many troubadours, and Eble II was himself a poet, although apparently none of his works has survived. The reference is thought to indicate the existence of two competing schools of poetic composition among the early troubadours, with Eble II as the head and patron of the school that upheld the more idealistic view of courtly love against the propagators of the trobar clos or difficult and dark style. Bernart, according to this hypothesis, became the principal representative of this idealist school among the second generation of troubadours. The popular story of Bernart's humble origins stems also from his vida and from a satirical poem by his slightly younger contemporary Peire d'Alvernhe. The vida states that his father was either a servant, a baker or a foot soldier (in Peire's version, a ‘worthy wielder of the laburnum bow’), and his mother either a servant or a baker (Peire: ‘she fired the oven and gathered twigs’). -

Mouvance and Authorship in Heinrich Von Morungen

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Songs of the Self: Authorship and Mastery in Minnesang Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/87n0t2tm Author Fockele, Kenneth Elswick Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Songs of the Self: Authorship and Mastery in Minnesang by Kenneth Elswick Fockele A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German and Medieval Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Niklaus Largier, chair Professor Elaine Tennant Professor Frank Bezner Fall 2016 Songs of the Self: Authorship and Mastery in Minnesang © 2016 by Kenneth Elswick Fockele Abstract Songs of the Self: Authorship and Mastery in Minnesang by Kenneth Elswick Fockele Doctor of Philosophy in German and Medieval Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Niklaus Largier, Chair Despite the centrality of medieval courtly love lyric, or Minnesang, to the canon of German literature, its interpretation has been shaped in large degree by what is not known about it—that is, the lack of information about its authors. This has led on the one hand to functional approaches that treat the authors as a class subject to sociological analysis, and on the other to approaches that emphasize the fictionality of Minnesang as a form of role- playing in which genre conventions supersede individual contributions. I argue that the men who composed and performed these songs at court were, in fact, using them to create and curate individual profiles for themselves. -

Poésie Et Enseignement De La Courtoisie Dans Le Duché D’Aquitaine Aux Xiie Et Xiiie Siècles : Examen De Quatre Ensenhamens Sébastien-Abel Laurent

Poésie et enseignement de la courtoisie dans le duché d’Aquitaine aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles : examen de quatre ensenhamens Sébastien-Abel Laurent To cite this version: Sébastien-Abel Laurent. Poésie et enseignement de la courtoisie dans le duché d’Aquitaine aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles : examen de quatre ensenhamens. 143e congrès, CTHS, Apr 2018, Paris, France. 10.4000/books.cths.8151. halshs-02885129 HAL Id: halshs-02885129 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02885129 Submitted on 30 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Dominique Briquel (dir.) Écriture et transmission des savoirs de l’Antiquité à nos jours Éditions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques Poésie et enseignement de la courtoisie dans le duché d’Aquitaine aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles : examen de quatre ensenhamens Sébastien-Abel Laurent DOI : 10.4000/books.cths.8151 Éditeur : Éditions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques Lieu d'édition : Éditions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques Année d'édition : 2020 Date de mise en ligne : 21 janvier 2020 Collection : Actes des congrès nationaux des sociétés historiques et scientifiques ISBN électronique : 9782735508969 http://books.openedition.org Référence électronique LAURENT, Sébastien-Abel. -

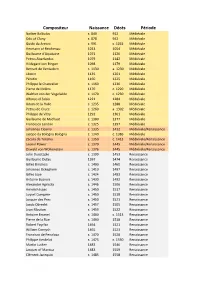

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

L'espressione Dell'identità Nella Lirica Romanza Medievale

L’espressione dell’identità nella lirica romanza medievale a cura di Federico Saviotti e Giuseppe Mascherpa L’espressione dell’identità nella lirica romanza medievale / a cura di Federico Saviotti e Giuseppe Mascherpa. – Pavia : Pavia University Press, 2016. – [VIII], 150 p. ; 24 cm. (Scientifica) http://purl.oclc.org/paviauniversitypress/9788869520471 ISBN 9788869520464 (brossura) ISBN 9788869520471 (e-book PDF) © 2016 Pavia University Press – Pavia ISBN: 978-88-6952-047-1 Nella sezione Scientifica Pavia University Press pubblica esclusivamente testi scientifici valutati e approvati dal Comitato scientifico-editoriale I diritti di traduzione, di memorizzazione elettronica, di riproduzione e di adattamento anche parziale, con qualsiasi mezzo, sono riservati per tutti i paesi. I curatori sono a disposizione degli aventi diritti con cui non abbiano potuto comunicare per eventuali omissioni o inesattezze. In copertina: Pavia, Archivio Storico Diocesano, Frammento di canzoniere provenzale, c. 2v (particolare) Prima edizione: dicembre 2016 Pavia University Press – Edizioni dell’Università degli Studi di Pavia Via Luino, 12 – 27100 Pavia (PV) Italia http://www.paviauniversitypress.it – [email protected] Printed in Italy Sommario Premessa Federico Saviotti, Giuseppe Mascherpa .........................................................................................VII Introduzione Per un’identità nel genere lirico medievale Federico Saviotti ............................................................................................................................... -

Troubadours NEW GROVE

Troubadours, trouvères. Lyric poets or poet-musicians of France in the 12th and 13th centuries. It is customary to describe as troubadours those poets who worked in the south of France and wrote in Provençal, the langue d’oc , whereas the trouvères worked in the north of France and wrote in French, the langue d’oil . I. Troubadour poetry 1. Introduction. The troubadours were the earliest and most significant exponents of the arts of music and poetry in medieval Western vernacular culture. Their influence spread throughout the Middle Ages and beyond into French (the trouvères, see §II below), German, Italian, Spanish, English and other European languages. The first centre of troubadour song seems to have been Poitiers, but the main area extended from the Atlantic coast south of Bordeaux in the west, to the Alps bordering on Italy in the east. There were also ‘schools’ of troubadours in northern Italy itself and in Catalonia. Their influence, of course, spread much more widely. Pillet and Carstens (1933) named 460 troubadours; about 2600 of their poems survive, with melodies for roughly one in ten. The principal troubadours include AIMERIC DE PEGUILHAN ( c1190–c1221), ARNAUT DANIEL ( fl c1180–95), ARNAUT DE MAREUIL ( fl c1195), BERNART DE VENTADORN ( fl c1147–70), BERTRAN DE BORN ( fl c1159–95; d 1215), Cerveri de Girona ( fl c1259–85), FOLQUET DE MARSEILLE ( fl c1178–95; d 1231), GAUCELM FAIDIT ( fl c1172–1203), GUILLAUME IX , Duke of Aquitaine (1071–1126), GIRAUT DE BORNELH ( fl c1162–99), GUIRAUT RIQUIER ( fl c1254–92), JAUFRE RUDEL ( fl c1125–48), MARCABRU ( fl c1130–49), PEIRE D ’ALVERNHE ( fl c1149–68; d 1215), PEIRE CARDENAL ( fl c1205–72), PEIRE VIDAL ( fl c1183–c1204), PEIROL ( c1188–c1222), RAIMBAUT D ’AURENGA ( c1147–73), RAIMBAUT DE VAQEIRAS ( fl c1180–1205), RAIMON DE MIRAVAL ( fl c1191–c1229) and Sordello ( fl c1220–69; d 1269). -

Les Délices Intoxicates with Rare 14Th-Century Music (Jan

Les Délices intoxicates with rare 14th-century music (Jan. 14) by Daniel Hathaway The Cleveland-based period instrument ensemble Les Délices generally traffics in French Baroque music. That national repertoire overlays special mannerisms onto forms and harmonic progressions that are otherwise relatively familiar to our ears. But when Debra Nagy takes her colleagues and audiences back another three or four hundred years on an excursion into the French 14th century, we enter a musical world that operates under very different rules. On Sunday, challenging ears and expectations, Les Délices performed its program “Intoxicating,” featuring music by the well-known Guillaume de Machaut; the obscure composers Solage, Hasprois, Antonello de Caserta; and the ever-prolific Anonymous, to a capacity audience in Herr Chapel of Plymouth Church in Shaker Heights. In these pieces, text setting seems capricious rather than directly illustrative of the words. Musical phrases come in non-standard lengths, and harmonies meander rather than point toward clear musical goals. When the music does come to a halt at a cadence, it’s usually the result of the linear movement of melodic lines — often decked out with double leading tones. And sections and pieces end on unisons or open fifths without that middle note that signals major or minor in later music. But once you immerse yourself in the music and let it carry you along on its own itinerary, the experience is mesmerizing. Five excellent tour guides — soprano Elena Mullins, tenor Jason McStoots, and instrumentalists Scott Metcalfe, Charles Weaver, and Debra Nagy — led the journey through the program’s four sections with easy virtuosity.