Annotated Bibliography of African American Carillon Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mahalia Jackson (B

Mahalia Jackson (b. 10/26/11, d. 1/27/72) was born Mahala Jackson in the Uptown neighborhood of New Orleans, Louisiana, and began singing at the Mount Mariah Baptist Church there at the age of 4. She grew up in a very poor household, which contained thirteen people and a dog in a three-room dwelling. Her stage name “Mahalia” stems from her childhood nickname “Halie”. In 1927, at the age of 16 she moved to Chicago, Illinois in the midst of the Great Migration. She intended to study nursing, but after joining a local church she became a member of the Johnson Gospel Singers. She performed with the group for a number of years. She then started working with Thomas A. Dorsey, the gospel composer of “Precious Lord, Take My Hand”, and the two performed around the U.S., which helped tremendously in cultivating a future audience for her. While she made some recordings in the 1930’s, her first major success came with “Move On Up A Little Higher” in 1947, which sold millions of copies and became the highest selling gospel single in history. Her career blossomed, and on October 4, 1950 she became the first gospel singer to perform at Carnegie Hall, and she did so to a racially integrated audience. Also in the 1950’s she became an international star, being especially popular in France and Norway. Back at home, she made her debut on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1956, and appeared with Duke Ellington and his Orchestra at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1958. -

Royal Umd 0117E 18974.Pdf (465.4Kb)

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: SELECTED WORKS OF COMPOSERS ASSOCIATED WITH HOWARD UNIVERSITY Guericke Christopher Royal, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Chris Gekker School of Music Throughout its over 100 year history, Howard University has produced and attracted many talented composers of many musical genres. Limiting this project to any one genre or focus would have lessened the overall impact of the music they created and the inspiration that has been a lauded part of the institution. The project will demonstrate the various harmonic, melodic, rhythmic and emotional contributions of the selected composers through interpretation of their music on the trumpet. Composers have been connected to the university in three general ways: as students, alumni and faculty; as commissioned artists; and through the performance of their works by notable performers associated with Howard. The pieces selected for this project exemplify a wide range of musical expressions and compositional techniques, and hopefully have been presented in a way that allows the emotional impact of each piece to resonate in a unique fashion. The selected works tended to fall into the categories of A. Trumpet and Brass Works B. Spirituals/ Meditational/ Religious Works C. Popular and Jazz Pieces D. Organ or other Instrumental Works E. Works of Historical Reference or Significance In some cases, certain pieces may be categorized across multiple categories (e.g. an organ piece based on religious material). As this was also a recording project, great care was taken during the recording process to capture as much emotional content as possible through stereo microphone techniques and the use of high quality equipment. -

The Caravan Playlist 181 Friday, December 2, 2016 Hour 1 Artist

The Caravan Playlist 181 Friday, December 2, 2016 Hour 1 Artist Track CD/Source Label Neil Young Comes a Time Comes a Time Reprise - c 1978 3 Penny Acre Cowbird Rag and Bone 2 Penny Acre - c 2013 Steve Gillette & Cindy Mangsen Cornstalk Pony Live at Leu Gardens Steve Gillette - c 2007 Nitty Gritty Dirt Band Falling Down Slow Dirt Silver and Gold BGO Records - C 1976 The Honey Dewdrops Hills of My Home Silver Lining The Honey Dewdrops - c 2012 3 Penny Acre Mackinaw Rag and Bone 2 Penny Acre - c 2013 Rick Adams Blue Just Looks Black No Cover At The Door Rick Adams - c 2013 Rick Adams No Cover At The Door No Cover At The Door Rick Adams - c 2013 John Wakefield Carolina in My Mind Live at The Alexandria Museum Red River Radio Recording John Wakefield No One Brings Me Down Like You Live at The Alexandria Museum Red River Radio Recording John Wakefield Hold Me Still Live at The Alexandria Museum Red River Radio Recording John Wakefield Back To Broke Live at The Alexandria Museum Red River Radio Recording John Wakefield Take it Real Slow Live at The Alexandria Museum Red River Radio Recording John Wakefield Baby, Baby, Baby Live at The Alexandria Museum Red River Radio Recording Hour 2 Artist Track Concert Source Buddy Flett Mississippi Sea Live at The Alexandria Museum Red River Radio Recording Buddy Flett Tenaha Live at The Alexandria Museum Red River Radio Recording Buddy Flett & Josh Hyde Ain't No More Cane On The Brazos Live at The Alexandria Museum Red River Radio Recording Josh Hyde & Buddy Flett Dark Side Live at The Alexandria Museum -

Aaamc Issue 9 Chrono

of renowned rhythm and blues artists from this same time period lip-synch- ing to their hit recordings. These three aaamc mission: collections provide primary source The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, materials for researchers and students preservation, and dissemination of materi- and, thus, are invaluable additions to als for the purpose of research and study of our growing body of materials on African American music and culture. African American music and popular www.indiana.edu/~aaamc culture. The Archives has begun analyzing data from the project Black Music in Dutch Culture by annotating video No. 9, Fall 2004 recordings made during field research conducted in the Netherlands from 1998–2003. This research documents IN THIS ISSUE: the performance of African American music by Dutch musicians and the Letter ways this music has been integrated into the fabric of Dutch culture. The • From the Desk of the Director ...........................1 “The legacy of Ray In the Vault Charles is a reminder • Donations .............................1 of the importance of documenting and • Featured Collections: preserving the Nelson George .................2 achievements of Phyl Garland ....................2 creative artists and making this Arizona Dranes.................5 information available to students, Events researchers, Tribute.................................3 performers, and the • Ray Charles general public.” 1930-2004 photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Collection) photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Visiting Scholars reminder of the importance of docu- annotation component of this project is • Scot Brown ......................4 From the Desk menting and preserving the achieve- part of a joint initiative of Indiana of the Director ments of creative artists and making University and the University of this information available to students, Michigan that is funded by the On June 10, 2004, the world lost a researchers, performers, and the gener- Andrew W. -

The "Stars for Freedom" Rally

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Selma-to-Montgomery National Historic Trail The "Stars for Freedom" Rally March 24,1965 The "March to Montgomery" held the promise of fulfilling the hopes of many Americans who desired to witness the reality of freedom and liberty for all citizens. It was a movement which drew many luminaries of American society, including internationally-known performers and artists. In a drenching rain, on the fourth day, March 24th, carloads and busloads of participants joined the march as U.S. Highway 80 widened to four lanes, thus allowing a greater volume of participants than the court- imposed 300-person limitation when the roadway was narrower. There were many well-known celebrities among the more than 25,000 persons camped on the 36-acre grounds of the City of St. Jude, a Catholic social services complex which included a school, hospital, and other service facilities, located within the Washington Park neighborhood. This fourth campsite, situated on a rain-soaked playing field, held a flatbed trailer that served as a stage and a host of famous participants that provided the scene for an inspirational performance enjoyed by thousands on the dampened grounds. The event was organized and coordinated by the internationally acclaimed activist and screen star Harry Belafonte, on the evening of March 24, 1965. The night "the Stars" came out in Alabama Mr. Belafonte had been an acquaintance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. since 1956. He later raised thousands of dollars in funding support for the Freedom Riders and to bailout many protesters incarcerated during the era, including Dr. -

Yesterday (Beatles Song)

Yesterday (Beatles song) "Yesterday" is a song by English rock band the Bea- whether they had ever heard it before. Eventually it be- tles written by Paul McCartney (credited to Lennon– came like handing something in to the police. I thought McCartney) first released on the album Help! in the if no one claimed it after a few weeks then I could have United Kingdom in August 1965. it.”[5] “Yesterday”, with the B-side "Act Naturally", was re- Upon being convinced that he had not robbed anyone leased as a single in the United States in September 1965. of their melody, McCartney began writing lyrics to suit While it topped the American chart in October the song it. As Lennon and McCartney were known to do at the also hit the British top 10 in a cover version by Matt time, a substitute working lyric, titled “Scrambled Eggs” Monro. The song also appeared on the UK EP “Yester- (the working opening verse was “Scrambled eggs/Oh my day” in March 1966 and the Beatles’ US album Yesterday baby how I love your legs/Not as much as I love scram- and Today released in June 1966. bled eggs”), was used for the song until something more McCartney’s vocal and acoustic guitar, together with a suitable was written. In his biography, Paul McCartney: string quartet, essentially made for the first solo perfor- Many Years from Now, McCartney recalled: “So first of mance of the band. It remains popular today with more all I checked this melody out, and people said to me, 'No, than 2,200 cover versions[2] and is one of the most cov- it’s lovely, and I'm sure it’s all yours.' It took me a little ered songs in the history of recorded music.[note 1] “Yes- while to allow myself to claim it, but then like a prospec- terday” was voted the best song of the 20th century in a tor I finally staked my claim; stuck a little sign on it and said, 'Okay, it’s mine!' It had no words. -

Aint Gonna Study War No More / Down by the Riverside

The Danish Peace Academy 1 Holger Terp: Aint gonna study war no more Ain't gonna study war no more By Holger Terp American gospel, workers- and peace song. Author: Text: Unknown, after 1917. Music: John J. Nolan 1902. Alternative titles: “Ain' go'n' to study war no mo'”, “Ain't gonna grieve my Lord no more”, “Ain't Gwine to Study War No More”, “Down by de Ribberside”, “Down by the River”, “Down by the Riverside”, “Going to Pull My War-Clothes” and “Study war no more” A very old spiritual that was originally known as Study War No More. It started out as a song associated with the slaves’ struggle for freedom, but after the American Civil War (1861-65) it became a very high-spirited peace song for people who were fed up with fighting.1 And the folk singer Pete Seeger notes on the record “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy and Other Love Songs”, that: "'Down by the Riverside' is, of course, one of the oldest of the Negro spirituals, coming out of the South in the years following the Civil War."2 But is the song as we know it today really as old as it is claimed without any sources? The earliest printed version of “Ain't gonna study war no more” is from 1918; while the notes to the song were published in 1902 as music to a love song by John J. Nolan.3 1 http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/grovemusic/spirituals,_hymns,_gospel_songs.htm 2 Thanks to Ulf Sandberg, Sweden, for the Pete Seeger quote. -

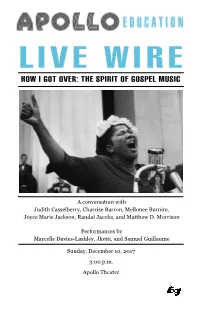

View the Program Book for How I Got Over

A conversation with Judith Casselberry, Charrise Barron, Mellonee Burnim, Joyce Marie Jackson, Randal Jacobs, and Matthew D. Morrison Performances by Marcelle Davies-Lashley, Jhetti, and Samuel Guillaume Sunday, December 10, 2017 3:00 p.m. Apollo Theater Front Cover: Mahalia Jackson; March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 1957 LIVE WIRE: HOW I GOT OVER - THE SPIRIT OF GOSPEL MUSIC In 1963, when Mahalia Jackson sang “How I Got Over” before 250,000 protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, she epitomized the sound and sentiment of Black Americans one hundred years after Emancipation. To sing of looking back to see “how I got over,” while protesting racial violence and social, civic, economic, and political oppression, both celebrated victories won and allowed all to envision current struggles in the past tense. Gospel is the good news. Look how far God has brought us. Look at where God will take us. On its face, the gospel song composed by Clara Ward in 1951, spoke to personal trials and tribulations overcome by the power of Jesus Christ. Black gospel music, however, has always occupied a space between the push to individualistic Christian salvation and community liberation in the context of an unjust society— a declaration of faith by the communal “I”. From its incubation at the turn of the 20th century to its emergence as a genre in the 1930s, gospel was the sound of Black people on the move. People with purpose, vision, and a spirit of experimentation— clear on what they left behind, unsure of what lay ahead. -

How Our Cultural Roots Inform Musical Heritage and Shape America's

How our cultural roots inform musical heritage and shape America’s sense of identity Music has an enduring power. Countries often call upon composers to create music that helps shape a national identity. To write music that captures America, many composers took inspiration from the folk music, spirituals and work songs of the African-American experience. By transforming these melodies and rhythms into art songs and symphonic works, composers remind us of the timeless relevance of music in our lives. Moreover, the presence of these authentic melodies in orchestral works acknowledges the role of music in shaping a national identity. Join us as we honor our classical American roots. Joseph Young, Conductor Dvorák’s landmark “New World Symphony” n the 1890’s, people in America were searching for music that might reflect their national identity. At the same time, of course, they were asking “what is America?” and “what does it mean to be American?” IOrchestral music of the day often imitated a grand European tradition. Could there be a uniquely American “sound”? Did we have music that conveyed a sense of America? Would American composers ever achieve Henry “Harry” T. Burleigh: recognition in the world? The Man Who Introduced Dvor˘ák to Spirituals To address those questions,˘ a visionary woman named Jeannette Thurber planned a As a young boy, new National Conservatory of Music in New York City, and sought to recruit an important American European composer to oversee the conservatory and hopefully to elevate the caliber composer of American music. She set her sights on a Czech composer named Antonin Dvor˘ák Henry (1841-1904) [pronounced di-VOR-zhak]. -

Songs of the Century

Songs of the Century T. Austin Graham hat is the time, the season, the historical context of a popular song? When is it most present in the world, best able Wto reflect, participate in, or construct some larger social reality? This essay will consider a few possible answers, exploring the ways that a song can exist in something as brief as a passing moment and as broad as a century. It will also suggest that when we hear those songs whose times have been the longest, we might not be hearing “songs” at all. Most people are likely to have an intuitive sense for how a song can contract and swell in history, suited to a certain context but capable of finding any number of others. Consider, for example, the various uses to which Joan Didion is able to put music in her generation-defining essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” a meditation on drifting youth and looming apocalypse in the days of the Haight-Ashbury counterculture. Songs create a powerful sense of time and place throughout the piece, with Didion nodding to the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Quick- silver Messenger Service, and “No Milk Today” by Herman’s Hermits, “a song I heard every morning in the cold late spring of 1967 on KRFC, the Flower Power Station, San Francisco.”1 But the music that speaks most directly and reverberates most widely in the essay is “For What It’s Worth,” the Buffalo Springfield single whose chiming guitar fifths and famous chorus—“Stop, hey, what’s that sound / Everybody look what’s going down”—make it instantly recognizable nearly five decades later.2 To listen to “For What It’s Worth” on Didion’s pages is to hear a song that exists in many registers and seems able to suffuse everything, from a snatch of conversation, to a set of political convictions, to nothing less than “The ’60s” itself. -

NEW MUSIC on COMPACT DISC 4/16/04 – 8/31/04 Amnesia

NEW MUSIC ON COMPACT DISC 4/16/04 – 8/31/04 Amnesia / Richard Thompson. AVRDM3225 Flashback / 38 Special. AVRDM3226 Ear-resistible / the Temptations. AVRDM3227 Koko Taylor. AVRDM3228 Like never before / Taj Mahal. AVRDM3229 Super hits of the '80s. AVRDM3230 Is this it / the Strokes. AVRDM3231 As time goes by : great love songs of the century / Ettore Stratta & his orchestra. AVRDM3232 Tiny music-- : songs from the Vatican gift shop / Stone Temple Pilots. AVRDM3233 Numbers : a Pythagorean theory tale / Cat Stevens. AVRDM3234 Back to earth / Cat Stevens. AVRDM3235 Izitso / Cat Stevens. AVRDM3236 Vertical man / Ringo Starr. AVRDM3237 Live in New York City / Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band. AVRDM3238 Dusty in Memphis / Dusty Springfield. AVRDM3239 I'll be around : and other hits. AVRDM3240 No one does it better / SoulDecision. AVRDM3241 Doin' something / Soulive. AVRDM3242 The very thought of you: the Decca years, 1951-1957 /Jeri Southern. AVRDM3243 Mighty love / Spinners. AVRDM3244 Candy from a stranger / Soul Asylum. AVRDM3245 Gone again / Patti Smith. AVRDM3246 Gung ho / Patti Smith. AVRDM3247 Freak show / Silverchair. AVRDM3248 '60s rock. The beat goes on. AVRDM3249 ‘60s rock. The beat goes on. AVRDM3250 Frank Sinatra sings his greatest hits / Frank Sinatra. AVRDM3251 The essence of Frank Sinatra / Frank Sinatra. AVRDM3252 Learn to croon / Frank Sinatra & Tommy Dorsey and his orchestra. AVRDM3253 It's all so new / Frank Sinatra & Tommy Dorsey and his orchestra. AVRDM3254 Film noir / Carly Simon. AVRDM3255 '70s radio hits. Volume 4. AVRDM3256 '70s radio hits. Volume 3. AVRV3257 '70s radio hits. Volume 1. AVRDM3258 Sentimental favorites. AVRDM3259 The very best of Neil Sedaka. AVRDM3260 Every day I have the blues / Jimmy Rushing. -

Old Chorale 032509X

“The Old Chorale” March 24, 2009 Volume 2 , Issue 3 Contents A Night at the Oscars 1 Tickets 1 “A Night at the Oscars” Dewey’s Dialog 2 Music FoTeam 2 In case you haven’t checked your calendar, our show is in 3½ C.R. Officers 2 weeks!!!! That’s three more rehearsals counting tonight. Thank you to all who showed up at our “advance” rehearsal last Saturday. Progress Upcoming Singouts 3 was made. And thank you to those who provided the food, donuts, I’ve Heard That Song 4 and coffee. Who is This C.R.? 5 We have taken on an unprecedented challenge, learning seven new Just for Fun 6 –7 songs in four months. I think it shows several things: 1) We can do it Mission Statement 8 if we want it bad enough; 2) With the right tools, the learning process is quicker, more fun, and more productive; 3) The Chord Rustlers are a fearsome group of dedicated Barbershoppers. Now it’s time to perfect what we’re learned and make our appearance on the show one that our audience won’t soon forget. We’ll hold up Upcoming Events our half of the show and let FRED entertain the audiences for their half. Sig and Dave need our support to have the show run smoothly; ♦ April 4 volunteer where needed and remember to offer support rather than Park County criticism. A little sugar draws more flies than vinegar! (I made that Pioneer Society up.) Sell the show!!! Perfect the music!!! And come pre pared to have Livingston a great time.