Nat “King” Cole's Civil War: How Pop Music's Intimate Sounds and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY14 Tappin' Study Guide

Student Matinee Series Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life Study Guide Created by Miller Grove High School Drama Class of Joyce Scott As part of the Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists’ Dramaturgy by Students Under the guidance of Teaching Artist Barry Stewart Mann Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life was produced at the Arena Theatre in Washington, DC, from Nov. 15 to Dec. 29, 2013 The Alliance Theatre Production runs from April 2 to May 4, 2014 The production will travel to Beverly Hills, California from May 9-24, 2014, and to the Cleveland Playhouse from May 30 to June 29, 2014. Reviews Keith Loria, on theatermania.com, called the show “a tender glimpse into the Hineses’ rise to fame and a touching tribute to a brother.” Benjamin Tomchik wrote in Broadway World, that the show “seems determined not only to love the audience, but to entertain them, and it succeeds at doing just that! While Tappin' Thru Life does have some flaws, it's hard to find anyone who isn't won over by Hines showmanship, humor, timing and above all else, talent.” In The Washington Post, Nelson Pressley wrote, “’Tappin’ is basically a breezy, personable concert. The show doesn’t flinch from hard-core nostalgia; the heart-on-his-sleeve Hines is too sentimental for that. It’s frankly schmaltzy, and it’s barely written — it zips through selected moments of Hines’s life, creating a mood more than telling a story. it’s a pleasure to be in the company of a shameless, ebullient vaudeville heart.” Maurice Hines Is . -

Mahalia Jackson (B

Mahalia Jackson (b. 10/26/11, d. 1/27/72) was born Mahala Jackson in the Uptown neighborhood of New Orleans, Louisiana, and began singing at the Mount Mariah Baptist Church there at the age of 4. She grew up in a very poor household, which contained thirteen people and a dog in a three-room dwelling. Her stage name “Mahalia” stems from her childhood nickname “Halie”. In 1927, at the age of 16 she moved to Chicago, Illinois in the midst of the Great Migration. She intended to study nursing, but after joining a local church she became a member of the Johnson Gospel Singers. She performed with the group for a number of years. She then started working with Thomas A. Dorsey, the gospel composer of “Precious Lord, Take My Hand”, and the two performed around the U.S., which helped tremendously in cultivating a future audience for her. While she made some recordings in the 1930’s, her first major success came with “Move On Up A Little Higher” in 1947, which sold millions of copies and became the highest selling gospel single in history. Her career blossomed, and on October 4, 1950 she became the first gospel singer to perform at Carnegie Hall, and she did so to a racially integrated audience. Also in the 1950’s she became an international star, being especially popular in France and Norway. Back at home, she made her debut on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1956, and appeared with Duke Ellington and his Orchestra at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1958. -

Jazz Lines Publications Fall Catalog 2009

Jazz lines PubLications faLL CataLog 2009 Vocal and Instrumental Big Band and Small Group Arrangements from Original Manuscripts & Accurate Transcriptions Jazz Lines Publications PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA www.ejazzlines.com [email protected] 518-587-1102 518-587-2325 (Fax) KEY: I=Instrumental; FV=Female Vocal; MV=Male Vocal; FVQ=Female Vocal Quartet; FVT= Femal Vocal Trio PERFORMER / TITLE CAT # DESCRIPTION STYLE PRICE FORMAT ARRANGER Here is the extended version of I've Got a Gal in Kalamazoo, made famous by the Glenn Miller Orchestra in the film Orchestra Wives. This chart differs significantly from the studio recorded version, and has a full chorus band intro, an interlude leading to the vocals, an extra band bridge into a vocal reprise, plus an added 24 bar band section to close. At five and a half minutes long, it's a (I'VE GOT A GAL IN) VOCAL / SWING - LL-2100 showstopper. The arrangement is scored for male vocalist plus a backing group of 5 - ideally girl, 3 tenors and baritone, and in the GLENN MILLER $ 65.00 MV/FVQ DIFF KALAMAZOO Saxes Alto 2 and Tenor 1 both double Clarinets. The Tenor solo is written on the 2nd Tenor part and also cross-cued on the male vocal part. The vocal whistling in the interlude is cued on the piano part, and we have written out the opening Trumpet solo in full. Trumpets 1-4: Eb6, Bb5, Bb5, Bb5; Trombones 1-4: Bb4, Ab4, Ab4, F4; Male Vocal: Db3 - Db4 (8 steps): Vocal key: Db to Gb. -

Sunday Nights with Walt Everything I Know I Learned from “The Wonderful World of Disney”

Sunday Nights with Walt Everything I Know I Learned from “The Wonderful World of Disney” Richard Rothrock Theme Park Press The Happiest Books on Earth www.ThemeParkPress.com Contents Introduction vii 1 “And Now Your Host, Walt Disney” 1 2 A Carousel of Color 9 3 A Carousel of American History 21 4 Adventures in Nature 49 Commercial Break: Making Mom’s Pizza 69 5 Life Lessons and Journeys with Our Pets and Horses 71 6 A Carousel of Fabulous, Faraway Places 89 7 Walt and His Park 109 8 The Show after Walt 119 Commercial Break: Fads and Evolutions 125 9 Solving a Mystery 129 10 Growing Up 143 11 Discovering the Classics 165 Commercial Break: Rich’s Top Ten 177 12 Learning the Ropes of Romance 179 13 Embracing the Future 191 Afterword 209 Acknowledgements 213 About the Author 215 About Theme Park Press 217 Introduction Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, Sunday nights at my house were different from the other nights of the week. It was the only night when my mother made pizza. It was the only night of the week when we could drink soda. It was the only night of the week when we could have candy for dessert. Iit was the only night of the week when we were allowed to eat dinner in front of the television. And the only shows we ever watched were Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom and The Wonderful World of Disney. (Mom sent us to bed as soon as Bonanza started.) For almost the entirety of my childhood, The Wonderful World of Disney was always there, even as I grew from a boy to a young man of eighteen, and even as my family moved from the small towns and farms of rural Indiana to the coal and steel towns of West Virginia to the towering spires of the Motor City in Michigan. -

Platinum Master Songlist

Platinum Master Songlist A B C D E 1 STANDARDS/ JAZZ VOCALS/SWING BALLADS/ E.L. -CONT 2 Ain't Misbehavin' Nat King Cole Over The Rainbow Israel Kamakawiwo'ole 3 Ain't I Good Too You Various Artists Paradise Sade 4 All Of Me Various Artists Purple Rain Prince 5 At Last Etta James Say John Mayer 6 Blue Moon Various Artists Saving All My Love Whitney Houston 7 Blue Skies Eva Cassidy Shower The People James Taylor 8 Don't Get Around Much Anymore Nat King Cole Stay With Me Sam Smith 9 Don't Know Why Nora Jones Sunrise, Sunset Fiddler On The Roof 10 Fly Me To The Moon Frank Sinatra The First Time ( Ever I Saw You Face)Roberta Flack 11 Georgia On My Mind Ray Charles Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeren 12 Girl From Impanema Various Artists Time After Time Cyndi Lauper 13 Haven't Met You Yet Michael Buble' Trouble Ray LaMontagne 14 Home Michael Buble' Tupelo Honey Van Morrison 15 I Get A Kick Out Of You Frank Sinatra Unforgettable Nat King Cole 16 It Don’t Mean A Thing Various Artists When You Say Nothing At All Alison Krause 17 It Had To Be You Harry Connick Jr. You Are The Best Thing Ray LaMontagne 18 Jump, Jive & Wail Brian Setzer Orchestra You Are The Sunshine Of My Life Stevie Wonder 19 La Vie En Rose Louis Armstrong You Look Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton 20 Let The Good Times Roll Louie Jordan 21 LOVE Various Artists 22 My Funny Valentine Various Artists JAZZ INSTRUMENTAL 23 Oranged Colored Sky Natalie Cole Birdland Joe Zawinul 24 Paper Moon Nat King Cole Breezin' George Benson 25 Route 66 Nat King Cole Chicago Song David Sanborn 26 Satin Doll Nancy Wilson Fragile Sting 27 She's No Lady Various Artists Just The Two Of Us Grover Washington Jr. -

1950S Culture Webquest Description: Created to Allow Students to Explore 1950S Culture

1950s Culture WebQuest Description: Created to allow students to explore 1950s culture. Grade Level: 9-12 Curriculum: Social Studies Keywords: 1950s, fifties, pop-culture Published On: 2008-03-01 09:50:33 Last Modified: 2008-02-29 08:10:21 WebQuest URL: http://zunal.com/webquest.php?w=8063 You will participating in a webquest to explore the culture and trends of the 1950s. The various websites will present you with information on everything from Levittown to the censorship of Elvis. Take your time going through the sites and remember to record your answers on your worksheet. Follow the instructions on the next page to navigate through the website. Record your answers on the worksheet provided. Welcome to the 1950s! Through this webquest you will be exploring the culture and trends of the 1950s. Remember to record what you find on your worksheet. 1. Congratulations! You have just been married. Take a look at this Home Economics textbook to find some tips on how to be the perfect housewife.2. Time to move to the suburbs! You and your spouse have decided to buy a house in Levittown, PA. Look at the four different models and decide which one fits your style and needs best.3. You need a new car to park in your new garage. Check out these classic cars and choose one you would like to have.4. To celebrate buying a new car you and your spouse decide to go to the drive-in for dinner and a movie. Click on the link above to read more about the drive-in. -

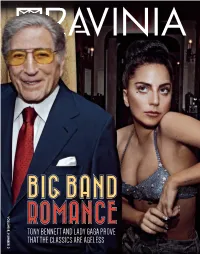

Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga Prove That the Classics Are

VOLUME 8, NUMBER 2 TONY BENNETT AND LADY GAGA PROVE THAT THE CLASSICS ARE AGELESS Untitled-2 2 5/27/15 11:56 AM Steven Klein 418 Sheridan Road Highland Park, IL 60035 847-266-5000 www.ravinia.org Welz Kauffman President and CEO Nick Pullia Communications Director, Executive Editor Nick Panfil Publications Manager, Editor Alexandra Pikeas Graphic Designer IN THIS ISSUE TABLE OF CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS 18 This Boy Does Cabaret 13 Message from John Anderson Since 1991 Alan Cumming conquers the world stage and Welz Kauffman 3453 Commercial Ave., Northbrook, IL 60062 with a “sappy” song in his heart. www.performancemedia.us 24 No Keeping Up 59 Foodstuff Gail McGrath Publisher & President Sharon Jones puts her soul into energetic 60 Ravinia’s Steans Music Institute Sheldon Levin Publisher & Director of Finance singing. REACH*TEACH*PLAY Account Managers 30 Big Band Romance 62 Sheryl Fisher - Mike Hedge - Arnie Hoffman Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga prove that 65 Lawn Clippings Karen Mathis - Greg Pigott the classics are ageless. East Coast 67 Salute to Sponsors 38 Long Train Runnin’ Manzo Media Group 610-527-7047 The Doobie Brothers have earned their 82 Annual Fund Donors Southwest station as rock icons. Betsy Gugick & Associates 972-387-1347 88 Corporate Partners 44 It’s Not Black and White Sales & Marketing Consultant Bobby McFerrin sees his own history 89 Corporate Matching Gifts David L. Strouse, Ltd. 847-835-5197 with Porgy and Bess. 90 Special Gifts Cathy Kiepura Graphic Designer 54 Swan Songs (and Symphonies) Lory Richards Graphic Designer James Conlon recalls his Ravinia themes 91 Board of Trustees A.J. -

The Attucks Theater September 4, 2020 | Source: Theater/ Words by Penny Neef

Spotlight: The Attucks Theater September 4, 2020 | Source: http://spotlightnews.press/index.php/2020/09/04/spotlight-the-attucks- theater/ Words by Penny Neef. Images as credited. Feature image by Mike Penello. In the early 20th century, segregation was a fact of life for African Americans in the South. It became a matter of law in 1926. In 1919, a group of African Americans from Norfolk and Portsmouth met to develop a cultural/business center in Norfolk where the black community “could be treated with dignity and respect.” The “Twin Cities Amusement Corporation” envisioned something like a modern-day town center. The businessmen obtained funding from black owned financial institutions in Hampton Roads. Twin Cities designed and built a movie theater/ retail/ office complex at the corner of Church Street and Virginia Beach Boulevard in Norfolk. Photo courtesy of the family of Harvey Johnson The businessmen chose 25-year-old architect Harvey Johnson to design a 600-seat “state of the art” theater with balconies and an orchestra pit. The Attucks Theatre is the only surviving theater in the United States that was designed, financed and built by African Americans. The Attucks was named after Crispus Attucks, a stevedore of African and Native American descent. He was the first patriot killed in the Revolutionary War at the Boston Massacre of 1770. The theatre featured a stage curtain with a dramatic depiction of the death of Crispus Attucks. Photo by Scott Wertz. The Attucks was an immediate success. It was known as the “Apollo Theatre of the South.” Legendary performers Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn, Nat King Cole, and B.B. -

Broadway's Smash Hit Beautiful – the Carole King Musical Makes Its

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Broadway’s smash hit Beautiful – The Carole King Musical makes its Worcester premiere September 26-29 Worcester, Mass. (September 9, 2019) The Tony® and Grammy® Award-winning Broadway hit Beautiful—The Carole King Musical, about the early life and career of the legendary and groundbreaking singer/songwriter, will make its Worcester premiere at The Hanover Theatre and Conservatory for the Performing Arts Thursday, September 26 - Sunday, September 29, locally sponsored by Fidelity Investments. Tickets are on sale now. “Carole King might be a native New Yorker, but her story of struggle and triumph is as universal as they come, and her music is loved the world over,” producer Paul Blake said. “I am thrilled that Beautiful continues to delight and entertain audiences around the globe, in England, Japan and Australia and that we are entering our fifth amazing year of touring the US. We are so grateful that over five million audience members have been entertained by our celebration of Carole's story and her timeless music.” With a book by Tony® and Academy® Award-nominee Douglas McGrath and direction by Marc Bruni and choreography by Josh Prince, Beautiful features a stunning array of beloved songs written by Gerry Goffin/Carole King and Barry Mann/Cynthia Weil. The show opened on Broadway at the Stephen Sondheim Theatre in January 2014, where it has since broken all box office records and became the highest grossing production in the Theatre’s history. The Original Broadway Cast Recording of Beautiful – The Carole King Musical (Ghostlight Records) won the 2015 Grammy Award for Best Musical Theater Album and is available on CD, digitally, and on vinyl. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

Song Lyrics of the 1950S

Song Lyrics of the 1950s 1951 C’mon a my house by Rosemary Clooney Because of you by Tony Bennett Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give Because of you you candy Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give a There's a song in my heart. you Apple a plum and apricot-a too eh Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house a come on My romance had its start. Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house I’m gonna give a Because of you, you The sun will shine. Figs and dates and grapes and cakes eh The moon and stars will say you're Come on-a my house, my house a come on mine, Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give Forever and never to part. you candy Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give I only live for your love and your kiss. you everything It's paradise to be near you like this. Because of you, (instrumental interlude) My life is now worthwhile, And I can smile, Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give you Christmas tree Because of you. Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give you Because of you, Marriage ring and a pomegranate too ah There's a song in my heart. -

Download Song List As

Top40/Current Bruno Mars 24K Magic Stronger (What Doesn't Kill Kelly Clarkson Treasure Bruno Mars You) Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Firework Katy Perry Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Hot N Cold Katy Perry Good as Hell Lizzo I Choose You Sara Bareilles Cake By The Ocean DNCE Till The World Ends Britney Spears Shut Up And Dance Walk The Moon Life is Better with You Michael Franti & Spearhead Don’t stop the music Rihanna Say Hey (I Love You) Michael Franti & Spearhead We Found Love Rihanna / Calvin Harris You Are The Best Thing Ray LaMontagne One Dance Drake Lovesong Adele Don't Start Now Dua Lipa Make you feel my love Adele Ride wit Me Nelly One and Only Adele Timber Pitbull/Ke$ha Crazy in Love Beyonce Perfect Ed Sheeran I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Let’s Get It Started Black Eyed Peas Cheap Thrills Sia Everything Michael Buble I Love It Icona Pop Dynomite Taio Cruz Die Young Kesha Crush Dave Matthews Band All of Me John Legend Where You Are Gavin DeGraw Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Forget You Cee Lo Green Party in the U.S.A. Miley Cyrus Feel So Close Calvin Harris Talk Dirty Jason Derulo Song for You Donny Hathaway Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jepsen This Is How We Do It Montell Jordan Brokenhearted Karmin No One Alicia Keys Party Rock Anthem LMFAO Waiting For Tonight Jennifer Lopez Starships Nicki Minaj Moves Like Jagger Maroon 5 Don't Stop The Party Pitbull This Love Maroon 5 Happy Pharrell Williams I'm Yours Jason Mraz Domino Jessie J Lucky Jason Mraz Club Can’t Handle Me Flo Rida Hey Ya! OutKast Good Feeling