Analysis of Airprox in UK Airspace: January to June 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GENERAL AVIATION REPORT GUIDANCE – December 2013

GENERAL AVIATION REPORT GUIDANCE – December 2013 Changes from November 2013 version Annex C – Wick Airport updated to reflect that it is approved for 3rd country aircraft imports No other changes to November version Introduction These instructions have been produced by Border Force are designed and published for General Aviation1 pilots, operators and owners of aircraft. They help you to complete and submit a General Aviation Report (GAR) and inform you about the types of airport you can use to make your journey. The instructions explain: - What a General Aviation Report (GAR) is What powers are used to require a report Where aircraft can land and take off When you are asked to submit a General Aviation Report (GAR); When, how and where to send the GAR How to complete the GAR How GAR information is used Custom requirements when travelling to the UK The immigration and documentation requirements to enter the UK What to do if you see something suspicious What is a General Aviation Report (GAR)? General Aviation pilots, operators and owners of aircraft making Common Travel Area2 and international journeys in some circumstances are required to report their expected journey to the Police and/or the Border Force command of the Home Office. Border Force and the Police request that the report is made using a GAR. The GAR helps Border Force and the Police in securing the UK border and preventing crime and terrorism. What powers are used to require a report? An operator or pilot of a general aviation aircraft is required to report in relation to international or Channel Islands journeys to or from the UK, unless they are travelling outbound directly from the UK to a destination in the European Union as specified under Sections 35 and 64 of the Customs & 1 The term General Aviation describes any aircraft not operating to a specific and published schedule 2 The Common Travel Area is comprised of Great Britain, Northern Ireland, Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands Excise Management Act 1979. -

General Aviation Report (GAR) Guidance – January 2021

General Aviation Report (GAR) Guidance – January 2021 Changes to the 2019 version of this guidance: • Updated Annex C (CoA list of airports) Submitting a General Aviation Report to Border Force under the Customs & Excise Management Act 1979 and to the Police under the Terrorism Act 2000. Introduction These instructions are for General Aviation (GA) pilots, operators and owners of aircraft. They provide information about completing and submitting a GAR and inform you about the types of airport you can use to make your journey. The instructions explain: 1. What is General Aviation Report (GAR) 2. Powers used to require a report 3. Where aircraft can land and take off 4. When, how and where to send the GAR 5. How to submit a GAR 6. How to complete the GAR 7. How GAR information is used 8. Customs requirements when travelling to the UK 9. Immigration and documentation requirements to enter the UK 10. What to do if you see something suspicious 1. General Aviation Report (GAR) GA pilots, operators and owners of aircraft making Common Travel Area1 and international journeys in some circumstances are required to report or provide notification of their expected journey to UK authorities. The information provided is used by Border Force and the Police to facilitate the smooth passage of legitimate persons and goods across the border and prevent crime and terrorism. 2. Powers used to require a report An operator or pilot of a GA aircraft is required to report in relation to international or Channel Island journeys to or from the UK under Sections 35 and 64 of the Customs & Excise Management Act 1979. -

SWANSEA Road, Rail and Sea Connectivity to LET Close Proximity to Swansea City Centre Warehousing / Office / and M4 Motorway (Junction 42) Open Storage Opportunities

SWANSEA Road, rail and sea connectivity TO LET Close proximity to Swansea city centre Warehousing / Office / and M4 motorway (Junction 42) Open Storage Opportunities Port of Swansea, SA1 1QR Situated in a top tier (‘A’) grant assisted area and within the Swansea Bay City Region Available Property Swansea City Centre A483 M4 SA1 Swansea Waterfront J42 - 4.8 km / 3 mi Delivering Property Solutions Swansea, Available Property Sat Nav: SA1 1QR Opportunity M4 J45 J47 J46 Our available sites, warehousing and office accommodation are situated within the secure confines of the Port of Swansea, located M4 J44 less than 2 miles from Swansea city centre. J47 12.8 km A48 A4067 Over recent years the Port has benefitted from major investment and offers opportunity M4 for port-related users to take advantage of both available quayside access and port J43 J45 12.8 km Winch Wen handling services, together with non-port related commercial occupiers seeking well A483 M4 located and secure storage land, existing warehousing and development plots for J42 the design and construction of bespoke business accommodation. Cockett Swansea Location Port Services St Thomas M4 Swansea A483 A4118 City Centre J42 4.8 km The Port of Swansea is conveniently located ABP’s most westerly positioned Port in South Wales providing ABP Port 3 miles, via the A483 dual carriageway, to shorter sailing times for vessels trading in/out of the West of of Swansea the west of Junction 42 of the M4 motorway, UK. The docks provides deep sea accessibility (Length: 200m, A4067 offering excellent road connectivity. -

Ministry of Defence: Competition in the Provision of Sufport Services

NATIONAL AUDIT OFFICE REPORTBY THE COMPTROLLERAND AUQITORGENERAL Ministryof Defence:Competition in the Provisionof SupportServices ORDERED BY THE HOUSE OF COMMONS TO BE PRINTED 10 JULY 1992 LONDON: HMSO 133 f7.25 NET MINISTRY OF DEFEhKEz COMPETITION IN THE PROVISION OF SUPPORT SERVICES This report has been prepared under Section 6 of the National Audit Act, 1983 for presentation to the House of Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the Act. John Bourn National Audit Office Comptroller and Auditor General 22 June 1992 The Comptroller and Auditor General is the head of the National Audit Office employing some 900 staff. He, and the NAO, are totally independent of Government. He certifies the accounts of all Government departments and a wide range of other public sector bodies; and he has statutory authority to report to Parliament on the economy, efficiency and effectiveness with which departments and other bodies haveused their resources. MINISTRY OF DEFENCE: COMPETITION IN THE PROVISION OF SUFPORT SERVICES Contents Pages Summary and conclusions 1 Part 1: Introduction 8 Part 2: Progress in applying competition to the provision of support services 11 Part 3: Maximising the benefits of competition 19 Part 4: Monitoring the performance of contractors 23 Appendices I. Examples of services provided wholly OI in part by contractors 27 2. Locations visited by the National Audit Office at which activities had been market tested 29 3. Market testing proposals: 1991-92 to 1993-94 30 4. Progress in mandatory areas 32 5. Use of the private sector in the provision of training 34 MNISTRY OF DEFENCE: COMPETITION IN THE PROVISION OF SUPPORT SERVICES Summary and conclusions 1 Government policy is that, where possible, work carried out by departments should be market tested-that is, subjected to competition and a contract let if it makes management sense and will improve value for money. -

Flying Clubs and Schools

A P 3 IR A PR CR 1 IC A G E FT E S, , YOUR COMPLE TE GUI DE C CO S O U N R TA S C ES TO UK AND OVERSEAS UK clubs TS , and schools Choose your region, county and read down for the page number FLYING CLUBS Bedfordshire . 34 Berkshire . 38 Buckinghamshire . 39 Cambridgeshire . 35 Cheshire . 51 Cornwall . 44 AND SCHOOLS Co Durham . 53 Cumbria . 51 Derbyshire . 48 elcome to your new-look Devon . 44 Dorset . 45 Where To Fly Guide listing for Essex . 35 2009. Whatever your reason Gloucestershire . 46 Wfor flying, this is the place to Hampshire . 40 Herefordshire . 48 start. We’ve made it easier to find a Lochs and Hertfordshire . 37 school and club by colour coding mountains in Isle of Wight . 40 regions and then listing by county – Scotland Kent . 40 Grampian Lancashire . 52 simply use the map opposite to find PAGE 55 Highlands Leicestershire . 48 the page number that corresponds Lincolnshire . 48 to you. Clubs and schools from Greater London . 42 Merseyside . 53 abroad are also listed. Flying rates Tayside Norfolk . 38 are quoted by the hour and we asked Northamptonshire . 49 Northumberland . 54 the schools to include fuel, VAT and base Fife Nottinghamshire . 49 landing fees unless indicated. Central Hills and Dales Oxfordshire . 42 Also listed are courses, specialist training Lothian of the Shropshire . 50 and PPL ratings – everything you could North East Somerset . 47 Strathclyde Staffordshire . 50 Borders want from flying in 2009 is here! PAGE 53 Suffolk . 38 Surrey . 42 Dumfries Northumberland Sussex . 43 The luscious & Galloway Warwickshire . -

Northumberland National Park Exterior Lighting Master Plan

EXTERIOR LIGHTING MASTER PLAN Prepared for: Northumberland National Park Authority and Kielder Water & Forest Park By James H Paterson BA(Hons), CEng, FILP, MCIBSE Lighting Consultancy And Design Services Ltd. Rosemount House, Well Road, Moffat DG10 9BT. Tel: 01683 220 299 Version 2. July 2013 Exterior Lighting Master Plan Issue 04.2013 Northumberland National Park Authority combined with Kielder Water & Forest Park Development Trust Dark Sky Park - Exterior Lighting Master Plan Contents 1 Preamble 1.1.1 Introduction to Lighting Master Plans for Dark Sky Status 1.1.2 Summary of Dark Sky Plan Statements 1.2 Introduction to Northumberland National Park and Kielder Water & Forest Park 1.2.1 Northumberland National Park 1.2.2 Kielder Water & Forest Park 1.3 The Astronomers’ Viewpoint 1.4 Night Sky Darkness Evaluation 1.5 Technical Lighting Data 1.6 “Fully Shielded” Concept Visualisation as Electronic Model 1.7 Environmental Zone Concept 1.8 Typical Task and Network Illuminance 2 Dark Sky Park Concept and Basic Light Limitation Plan 2.1 Dark Sky Park – Concept 2.2 Switching Regime (Time Limited) 2.3 Basic Light Limitation Plan - Environmental Zone E0's 2.4 Basic Light Limitation Plan - Environmental Zone E1 2.5 External Zone – South Scotland / North England Dark Sky Band 2.6 External Zone – Dark Sky Light Limitation – Environmental Zone E2 3 Planning Requirements 3.1 General 3.2 Design Stage 3.3 Non-photometric Lumen Cap method for domestic exterior lighting 3.4 Sports Lighting 4 Special Lighting Application Considerations 5 Existing Lighting -

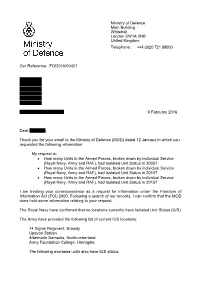

List of Current Isolated Unit Status (ISU) Locations for the Army And

Ministry of Defence Main Building Whitehall London SW1A 2HB United Kingdom Telephone : +44 (0)20 721 89000 Our Reference: FOI2016/00421 9 February 2016 Dear , Thank you for your email to the Ministry of Defence (MOD) dated 12 January in which you requested the following information: My request is: How many Units in the Armed Forces, broken down by individual Service (Royal Navy, Army and RAF), had Isolated Unit Status in 2005? How many Units in the Armed Forces, broken down by individual Service (Royal Navy, Army and RAF), had Isolated Unit Status in 2010? How many Units in the Armed Forces, broken down by individual Service (Royal Navy, Army and RAF), had Isolated Unit Status in 2015? I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOI) 2000. Following a search of our records, I can confirm that the MOD does hold some information relating to your request. The Royal Navy have confirmed that no locations currently have Isolated Unit Status (IUS) The Army have provided the following list of current IUS locations: 14 Signal Regiment, Brawdy Upavon Station Albemarle Barracks, Northumberland Army Foundation College, Harrogate The following overseas units also have IUS status: British Army Training Unit Kenya British Army Training Unit Suffield (Canada) British Army Training and Support Unit Belize Nepal Brunei The Royal Air Force (RAF) has provided the following current IUS locations: RAF Boulmer Remote Radar Head Benbecula RAF Fylingdales Force Development Training Centre Fairbourne RAF Honington RAF Linton-On-Ouse RAF Leeming RAF Staxton Wold RAF Spadeadam RAF Valley RAF Marham Please note that information prior to 2011 is not held. -

General Aviation Report (GAR) Guidance – July 2018

General Aviation Report (GAR) guidance – July 2018 Changes to the March 2015 version of this guidance: • Change in Police logo • New emergency contact details • New contact details for the National Advice Service • Updated Annex C (CoA list of airports) • Police authority contact details (ANNEX D) Submitting a General Aviation Report to Police under the Terrorism Act 2000 and to Border Force under the Customs & Excise Management Act 1979. Introduction These instructions produced by Border Force, are designed and published for General Aviation pilots, operators and owners of aircraft. They help you to complete and submit a General Aviation Report (GAR) and inform you about the types of airport you can use to make your journey. The instructions explain: 1. What a General Aviation Report (GAR) is 2. Powers used to require a report 3. Where aircraft can land and take off 4. When, how and where to send the GAR 5. How to submit a GAR 6. How to complete the GAR 7. How GAR information is used 8. Customs requirements when travelling to the UK 9. Immigration and documentation requirements to enter the UK 10. What to do if you see something suspicious 1. What a General Aviation Report (GAR) is General Aviation pilots, operators and owners of aircraft making Common Travel Area1 and international journeys in some circumstances are required to report their expected journey to UK authorities. The GAR is used by Border Force and the Police to facilitate the smooth passage of legitimate persons and goods across the border and prevent crime and terrorism. 2. Powers used to require a report An operator or pilot of a general aviation aircraft is required to report in relation to international or Channel Islands journeys to or from the UK, unless they are travelling outbound directly from the UK 1 The Common Travel Area is comprised of Great Britain, Northern Ireland, Republic of Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands 1 to a destination in the European Union as specified under Sections 35 and 64 of the Customs & Excise Management Act 1979. -

Consultation Response PA14. Welsh Local Government Association PDF

NAfW inquiry into international connectivity through Welsh ports and airports February 2012 INTRODUCTION 1. The Welsh Local Government Association (WLGA) represents the 22 local authorities in Wales, and the three national park authorities, the three fire and rescue authorities, and four police authorities are associate members. 2. It seeks to provide representation to local authorities within an emerging policy framework that satisfies the key priorities of our members and delivers a broad range of services that add value to Welsh Local Government and the communities they serve. 3. The WLGA welcomes this opportunity to feed comments into the NAfW‟s inquiry into international connectivity through Welsh ports and airports. Tables 1 and 2 below show that local authorities have a major interest in this issue with ten authorities having an airport/aircraft facility in their area and eight having a port – six have both. Overall, twelve authorities have an airport and/or a port – all of varying degrees of scale and activity. (In addition there are a number of former ports that have ceased to operate on a large scale but now house other activities including fishing and tourism related activity). Table 1 Airports in Wales Local authority Airport name Location Usage area Welshpool airport Welshpool Powys Public RAF Saint Athan St Athan Vale of Glamorgan Military Haverfordwest /Withybush Rudbaxton Pembrokeshire Public Aerodrome Cardiff Airport Rhoose Vale of Glamorgan Public Swansea Airport Pennard Swansea Public Pembrey airport Pembrey Carmarthenshire -

Annual Review 2019

ANNUAL REVIEW AND IMPACT REPORT 2019 CONTENTS OUR VISION OUR PURPOSE CHAIR’S MESSAGE 4 No member of To understand and IN 2019 WE SPENT 6 the RAF Family support each and CENTENARY 8 will ever face every member of FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE 10 adversity alone. the RAF Family, WELLBEING BREAKS 20 FAMILY AND RELATIONSHIPS 24 whenever they EMOTIONAL WELLBEING 28 need us. INDEPENDENT LIVING 32 TRANSITION 36 For 100 years, we have been the RAF’s oldest friend – loyal, WORKING IN PARTNERSHIP 40 generous and always there. We support current and former FUNDRAISING HIGHLIGHTS 42 members of the RAF, their partners and families, providing THANKING OUR DONORS 47 practical, emotional and financial help whenever they need FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 48 us. We are committed to getting them through tough times, CONTROLLER’S MESSAGE 50 whatever life throws at them. Cover photo: Jacob Newson meets Second World War veteran, and former Spitfire pilot, Allan Scott DFM at a special event in Oxfordshire, organised by Aces High. Jacob raised £6K for the Fund in 2019 2 3 MARKING 100 YEARS OF THE RAF BENEVOLENT FUND In 2019 we celebrated our centenary by launching an ambitious new campaign to find the veterans who need our help – and it has been a resounding success. As we approached the end of our first 2019 saw us make tremendous strides time and expertise and our amazing century, we felt exceptionally proud of towards this aim. Alongside superb donors and fundraisers for contributing our achievements. Side by side, shoulder centenary celebrations, we supported so generously. I would particularly to shoulder, we had been with the RAF an amazing 71,700 RAF Family like to express my gratitude to our Family every step of the way for 100 members – a quarter more than in outgoing Controller, David Murray, for years. -

General Aviation Report

General Aviation Report Completion and Submission Instructions Instructions for completion Aircraft Details 1. Aircraft registration should be as per ICAO flightplan – no hyphens or spaces 2. Type should be ICAO abbreviation or in full 3. Usual Base – Airfield/Airport where aircraft is normally or nominally based 4. Owner/Operator – Registered owner or operator of aircraft 5. Crew contact no. – Should be supplied in case of queries with your GAR 6. Is the Aircraft VAT paid in the UK/Isle of Man – YES or NO 7. Is Aircraft in ‘Free Circulation’ within the EU – YES or NO Aircraft imported from outside the EU are in free circulation in the EU when all import formalities have been complied with and all duties, levies or equivalent charges have been paid and not refunded. Free circulation aircraft that have previously been exported from the EU maybe eligible to Returned Goods relief subject to certain conditions, see Notice 236. For general enquiries about aircraft imports contact the Advice Centre on 01624 648130 Flight Details 1. Departure/Arrival – From & To can be ICAO code or in full if ‘ZZZZ’ would be used in the flightplan 2. Time – should be in UTC 3. Reason for visit to EU – Based – Aircraft is based within the EU and all import formalities have been completed Short Term Visit a) For aircraft not in free circulation and registered outside the EU, temporarily imported for private or commercial transport use – relief from customs import charges may be available under ‘Temporary Admission’ – see Notice 308. Whilst under Temporary Admission only repairs to maintain the aircraft in the same condition as imported may be carried out. -

Of Conflict the Archaeology

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF CONFLICT Introduction by Richard Morris There can hardly be an English field that does still left with a question: why have the prosaic not contain some martial debris – an earthwork, traces of structures which were often stereotyped There is more to war than a splinter of shrapnel, a Tommy’s button. A and mass-produced become so interesting? weapons and fighting.The substantial part of our archaeological inheritance growth of interest in 20th- has to do with war or defence – hillforts, Roman Part of the answer, I think, is that there is more to century military remains is marching camps, castles, coastal forts, martello war than weapons and fighting. One reason for part of a wider span of social towers, fortified houses – and it is not just sites the growth of interest in 20th-century military evoking ancient conflict for which nations now remains is that it is not a stand-alone movement archaeology care.The 20th century’s two great wars, and the but part of the wider span of social archaeology. tense Cold War that followed, have become It encompasses the everyday lives of ordinary archaeological projects. Amid a spate of public- people and families, and hence themes which ation, heritage agencies seek military installations archaeology has hitherto not been accustomed to of all kinds for protection and display. approach, such as housing, bereavement, mourning, expectations.This wider span has Why do we study such remains? Indeed, should extended archaeology’s range from the nationally we study them? We should ask, for there are important and monumental to the routine and some who have qualms.