Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.5.T65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Langston Hughes

Classic Poetry Series Langston Hughes - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: PoemHunter.Com - The World's Poetry Archive Langston Hughes (February 1, 1902 – May 22, 1967) an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist. He was one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form jazz poetry. Hughes is best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that "Harlem was in vogue." Biography Ancestry and Childhood Both of Hughes' paternal and maternal great-grandmothers were African-American, his maternal great-grandfather was white and of Scottish descent. A paternal great-grandfather was of European Jewish descent. Hughes's maternal grandmother Mary Patterson was of African-American, French, English and Native American descent. One of the first women to attend Oberlin College, she first married Lewis Sheridan Leary, also of mixed race. Lewis Sheridan Leary subsequently joined John Brown's Raid on Harper's Ferry in 1859 and died from his wounds. In 1869 the widow Mary Patterson Leary married again, into the elite, politically active Langston family. Her second husband was Charles Henry Langston, of African American, Native American, and Euro-American ancestry. He and his younger brother John Mercer Langston worked for the abolitionist cause and helped lead the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society in 1858. Charles Langston later moved to Kansas, where he was active as an educator and activist for voting and rights for African Americans. Charles and Mary's daughter Caroline was the mother of Langston Hughes. Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, the second child of school teacher Carrie (Caroline) Mercer Langston and James Nathaniel Hughes (1871–1934). -

Research Scholar an International Refereed E-Journal of Literary Explorations

ISSN 2320 – 6101 Research Scholar www.researchscholar.co.in An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations PORTRAYAL OF RACIAL-GENDER ISSUES IN THE POEMS OF LANGSTON HUGHES B.Sreekanth Reddy Research Scholar JNTUA, Anantapur Andhra Pradesh, India ABSTRACT From time immemorial, racial gender issues are a constant subject for discussion. The spread of education, rising sense of awareness have made many eminent scholars to bring out the racial and gender issues to limelight. It is the poets way of exposing the atrocities and the painful experiences of the colored people in America and other countries. Among the galaxy of many black scholars, Langston Hughes is of considerable importance. So an attempt is made to portray the issues of racism and gender inequalities as presented by Langston Hughes in his poems. Keywords :- Colored, Apartheid, Suppression, Pessimism Langston Hughes, a dominant black poet of the Harlem Renaissance, is noted for his representation of Afro-American gender race and culture. His exploration of the convergence of race, gender and culture earned him the title, ‘The Shakespeare of Harlem.’ The thematic scope of his poetry covers the faithful portrayal of social realism, primitive naturalism and democratic current of protest against racial and sexual injustice in America. To Hughes it seems that identity is in-separable from the individual and society. The vigorous force of his poetry is derived from the collective consciousness of his race. Hence, he could be called a true cultural ambassador of his race. His intellectual observations show his strong ethnic sense of origin, nativity and identity. Associated with other literary figures at Harlem like Jean Toomer, Zora Neale Henstar, Countee Cullan, W.E.B Du’ Bois and Claude Mckay, the poet was a witness to socio-political ups and downs in that particular period. -

Of the Blues Aesthetic

Skansgaard 1 The “Aesthetic” of the Blues Aesthetic Michael Ryan Skansgaard Homerton College September 2018 This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Skansgaard 2 Declaration: This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. At 79,829 words, the thesis does not exceed the regulation length, including footnotes, references and appendices but excluding the bibliography. This work follows the guidelines of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers. Acknowledgements: This study has benefitted from the advice of Fiona Green and Philip Coleman, whose feedback has led to a revitalised introduction and conclusion. I am also indebted to Donna Akiba Sullivan Harper, Robert Dostal, Kristen Treen, Matthew Holman, and Pulane Mpotokwane, who have provided feedback on various chapters; to Simon Jarvis, Geoff Ward, and Ewan Jones, who have served as advisers; and especially to my supervisor, Michael D. -

Langston Hughes: Voice Among Voices

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1991 Volume III: Afro-American Autobiography Langston Hughes: Voice Among Voices Curriculum Unit 91.03.01 by G. Casey Cassidy I. Introduction Over the past two years, while participating in the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute, I have written extensive units detailing the lives and creations of the Wright Brothers and Edward Hopper. When I set out to research these folks, I decided to read as much as possible about them from their childhood to their formative years, and then to accompany them through their great achievements. With this pattern in mind, I decided to read Langston Hughes, never realizing the monumental literary portfolio that this gentleman produced. His literary accomplishments are well represented through his poetry, his fiction, and his drama. His short stories were written utilizing a character named Jesse B. Simple, a universal, charming figure within whom we all can see a little bit of ourselves, usually in a humorous and honest capacity. His poetry often conveyed serious messages. Although his story was seldom pleasant, he told it with understanding and with hope. His novels, especially Not Without Laughter, created a warm human picture of Negro life in Black America. The family was very important to Langston Hughes, but so were the forces that surrounded the family—the racial discrimination, the violence of society, the unfairness of educational opportunities, and the right to share in the American dream of opportunity and freedom. It’s to these high ideals of opportunity and freedom that my research and efforts will be devoted this year as my curriculum unit develops. -

“Mother to Son” (1922)

Selected Poems — Langston Hughes “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” (1920) I’ve known rivers: I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins. My soul has grown deep like the rivers. I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young. I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep. I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it. I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset. I’ve known rivers: Ancient, dusky rivers. My soul has grown deep like the rivers. “Mother to Son” (1922) Well, son, I’ll tell you: Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair. It’s had tacks in it, And splinters, And boards torn up, And places with no carpet on the floor— Bare. But all the time I’se been a-climbin’ on, And reachin’ landin’s, And turnin’ corners, And sometimes goin’ in the dark Where there ain’t been no light. So boy, don’t you turn back. Don’t you set down on the steps ’Cause you finds it’s kinder hard. Don’t you fall now— For I’se still goin’, honey, I’se still climbin’, And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair. “The Weary Blues” (1925) Droning a drowsy syncopated tune, Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon, I heard a Negro play. Down on Lenox Avenue the other night By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light He did a lazy sway . -

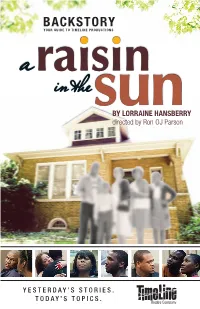

Backstory Your Guide to Timeline Productions

BACKSTORY YOUR GUIDE TO TIMELINE PRODUCTIONS BY LORRAINE HANSBERRY directed by Ron OJ Parson YESTERDAY’S STORIES. TODAY’S TOPICS. From Artistic Director PJ Powers Hansberry v. Lee A Timeline of the a message the history Harlem Renaissance and Civil Rights from 1900 to 1955 play ever set in Chicago—has career achievement. But they n 1937, Lorraine Hansberry’s sold to black families. Lee felt as much to say now as it did all see their dreams as unnat- Ifather decided to purchase a Hansberry had purchased the 1900 U.S. census records a then. While Hansberry wrote tainable if they remain where new family home in Washing- property in violation of the total population of 76,994,575, during a time that feels distant they currently dwell. ton Park, Chicago. A scholar Property Owners Associa- including a black population of (preceding the Civil Rights 8,833,944 (11.6%). So, why this play again? A and successful business man, tion’s agreement and sued for movement), Chicago was then Carl was an active member $100,000. She won her case “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” elcome to TimeLine’s Raisin in the Sun is about our and is now a tale of two cities, of the Chicago chapter of the at the Illinois Supreme Court. composed by James Weldon 17th season and community and the ever-shift- W splintered into neighborhoods NAACP and socialized with The case then went to the Johnson and J. Rosamond Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin ing but ever-existing neighbor- with stark contrasts. -

MISCELANEA 60.Indb

RESILIENCE AS A FORM OF CONTESTATION IN LANGSTON HUGHES’ EARLY POETRY LA RESILIENCIA COMO FORMA DE CONTESTACIÓN EN LA POESÍA TEMPRANA DE LANGSTON HUGHES ALBA FERNÁNDEZ ALONSO Universidad de Burgos [email protected] MARÍA AMOR BARROS DEL RÍO Universidad de Burgos [email protected] 91 Abstract The history of the African American community has been inexorably bound to the concepts of oppression, downgrading, racism, hatred and trauma. Although the association between racism and concomitant negative psychological outcome has been widely assessed, little work has been done to study the role of literature as a cultural means to promote resilience among this oppressed group. Langston Hughes (1902-1967) stands out as a novelist, poet and playwright, and is one of the primary contributors to the Harlem Renaissance movement. Following the framework of theories of resilience, this article analyses the representation of adversity and positive adaptation in Langston Hughes’s early stage poetry, and assesses his contribution to resilience among the African American people at a time of hardship and oppression. Keywords: Langston Hughes, African American poetry, resilience, Harlem Renaissance. Resumen La historia de la comunidad afroamericana ha estado inexorablemente vinculada a los conceptos de opresión, degradación, racismo, odio y trauma. Aunque la miscelánea: a journal of english and american studies 60 (2019): pp. 91-106 ISSN: 1137-6368 Alba Fernández Alonso y María Amor Barros del Río relación que hay entre el racismo y los efectos psicológicos negativos se ha estudiado ampliamente, aún son escasos los trabajos que analizan el papel de la literatura como medio cultural para promover la resiliencia entre los grupos oprimidos. -

Langston Hughes

A Selection of Poems by Langston Hughes © Kevin Bliss LANGSTON HUGHES (1902-1967) An Adolescent Bard James Langston Hughes began writing in junior high, and even at this early age was developing the voice that made him famous. Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri but his parents separated soon after his birth. His father moved to Cuba, then to Mexico, and his mother moved to the North to look for work. So as a child, Hughes lived with his grandmother in Lawrence, Kansas until he was thirteen. Hughes's grandmother, Mary Sampson Patterson Leary Langston, was prominent in the African American community in Lawrence. Her first husband had died at Harper's Ferry fighting with John Brown; her second husband, Langston Hughes's grandfather, was a prominent Kansas politician during Reconstruction. During the time Hughes lived with his grandmother, she often read to the young boy from W.E.B. DuBois’ new NAACP magazine The Crisis and DuBois’ book The Souls of Black Folk. However, she was old and poor and unable to give Hughes as much attention as he needed. Besides, Hughes felt hurt by both his mother and his father and was unable to understand why he was not allowed to live with either of them. These feelings of rejection caused him to grow up very insecure and unsure of himself. When Langston Hughes's was 13, his grandmother died, and his mother summoned him to her home in Lincoln, Illinois. Here, according to Hughes, he wrote his first verse and was named class poet of his eighth grade class. -

Harlem Renaissance Unit Resource Handbook for Middle School

Poetry Unit Middle School Harlem Renaissance Unit Written by: Deborah Dennard ELA Coordinator 6-12 Bibb County School District Unit Focus and Direction This unit of study focuses on the Harlem Renaissance. Students are to be immersed in the literature, art, dance, and music of this period. The short stories and literature is meant to be used for the literary standards. The essays and speeches are meant to be taught, using the reading informational standards. Students are to demonstrate mastery of the standards by writing poetry or analysis of the works. Speaking and listening is also an intricate part of this using. While it is important to include poetry in every unit of study, at times, it can be fun to focus solely on poetry. During this unit (2-4 weeks), students are immersed in poetry. They speak, listen to, write, and read poetry – individually and in groups. This sample unit framework can be used for middle and high school. Links are embedded at the end of each piece of reading. To build engagement, please play the videos beforehand to build schema and background knowledge. Poetry is meant to be read, heard, and enjoyed, rather than “studied.” Throughout the unit, read poems aloud daily and encourage students to read aloud poems of their choice. Ask students to respond to the words they hear and read in poems, and to picture the images that the words create. Students may say, “I don’t get it,” and say that they do not like poetry because they are fearful that they do not understand the “correct meaning.” For some of us as teachers, we share the same fear. -

Conversations Motivated by Love, Based in Wisdom, and Seasoned with Grace: Rhetorically Tracing “The Talk” African American Parents Have with Their Sons

ABSTRACT CONVERSATIONS MOTIVATED BY LOVE, BASED IN WISDOM, AND SEASONED WITH GRACE: RHETORICALLY TRACING “THE TALK” AFRICAN AMERICAN PARENTS HAVE WITH THEIR SONS This thesis presents a rhetorical analysis of The Talk African American parents have with their sons, preparing them for life within American civil society. Black male disposability provides a unique challenge for African American parents who struggle to support their sons in their development while informing them of the inherent risks of being Black and male in America. This thesis analyzes two of these conversations, one between Emmett Till and his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, prior to Till’s murder in 1955; and the conversations Lucia McBath and Ronald Davis had with their son, Jordan Davis, who was killed in 2012. This study uses a public memory and genre as a theoretical and methodological approach to further explore The Talk. This analysis concludes that there are three defining elements of The Talk: concern for the person, a cautionary tale, and potential violations. Melissa Harris May 2017 CONVERSATIONS MOTIVATED BY LOVE, BASED IN WISDOM, AND SEASONED WITH GRACE: RHETORICALLY TRACING “THE TALK” AFRICAN AMERICAN PARENTS HAVE WITH THEIR SONS by Melissa Harris A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication in the College of Arts and Humanities California State University, Fresno May 2017 © 2017 Melissa Harris APPROVED For the Department of Communication: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. -

The Weary Blues Mother To

NAME CLASS DATE LrrE RATU RE ACTWIrY The Weary Blues The Harlem Renaissance was a resurgence of literature, art, and music that centered in New York’s Harlem during the 1920s. Langston Hughes, who was known as the Poet Laureate of Harlem, wrote about the movement: ‘We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark- skinned selves without fear or shame.. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too... We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain free within ourselves.” The poem that follows was published in Hughes’s first volume, The Weary Blues, in 1926. Mother to Son Well, son, I’ll tell you: Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair. It’s had tacks in it, And splinters, And boards torn up, And places with no carpet on the floor— Bare. But all the time I’se been a-climbin’ on, And reachin’ landin’s, And turnin’ corners, And sometimes goin’ in the dark Where there ain’t been no light. So boy, don’t you turn back. Don’t you set down on the steps ‘Cause you finds it’s kinder hard. Don’t you fall now— For I’se still goin’, honey, I’se still climbin’, And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair. 1. In what ways is this poem both universal and specific? In your answer, con sider the main idea of the poem, the speaker, and the person being addressed. 2. Why is the image of a crystal stair a particularly vivid one? 3. -

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Langston Hughes' Mother to Son Well, Son, I'll

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Langston Hughes' Mother to Son Well, son, I'll tell you: Life for me ain't been no crystal stair. It's had tacks in it, And splinters, And boards torn up, And places with no carpet on the floor -- Bare. But all the time I'se been a-climbin' on, And reachin' landin's, And turnin' corners, And sometimes goin' in the dark Where there ain't been no light. So boy, don't you turn back. Don't you set down on the steps 'Cause you finds it's kinder hard. Don't you fall now -- For I'se still goin', honey, I'se still climbin', And life for me ain't been no crystal stair. Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906) We Wear the Mask WE wear the mask that grins and lies, It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,— This debt we pay to human guile; With torn and bleeding hearts we smile, And mouth with myriad subtleties. Why should the world be over-wise, In counting all our tears and sighs? Nay, let them only see us, while We wear the mask. We smile, but, O great Christ, our cries To thee from tortured souls arise. We sing, but oh the clay is vile Beneath our feet, and long the mile; But let the world dream otherwise, We wear the mask! 2 The Negro Mother By Langston Hughes Children, I come back today To tell you a story of the long dark way That I had to climb, that I had to know In order that the race might live and grow.