Historical Fabrications on the Internet: Recognition, Evaluation, and Use in Bibliographic Instruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eyes of the Sphinx: the Newest Evidence of Extraterrestrial Contact Ebook, Epub

THE EYES OF THE SPHINX: THE NEWEST EVIDENCE OF EXTRATERRESTRIAL CONTACT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Erich von Däniken | 278 pages | 01 Mar 1996 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780425151303 | English | New York, United States The Eyes of the Sphinx: The Newest Evidence of Extraterrestrial Contact PDF Book There are signs the Sphinx was unfinished. The Alien Agenda: Ancient alien theorists investigate evidence suggesting that extraterrestrials have played a pivotal role in the progress of mankind. Exactly what Khafre wanted the Sphinx to do for him or his kingdom is a matter of debate, but Lehner has theories about that, too, based partly on his work at the Sphinx Temple. Lovecraft and the invention of ancient astronauts. Aliens And Deadly Weapons: From gunpowder to missiles, were these lethal weapons the product of human innovation, or were they created with help from another, otherworldly source? Scientists suspect that over centuries, a mix of cultures including Maya, Zapotec, and Mixtec built the city that could house more than , people. In a dream, the statue, calling itself Horemakhet—or Horus-in-the-Horizon, the earliest known Egyptian name for the statue—addressed him. In keeping with the legend of Horemakhet, Thutmose may well have led the first attempt to restore the Sphinx. In recent years, researchers have used satellite imagery to discover more than additional geoglyphs, carefully poring over data to find patterns in the landscape. Later, he said, a "leading German archaeologist", dispatched to Ecuador to verify his claims, could not locate Moricz. Were they divine? Could it have anticipated the arrival of an extraterrestrial god? Also popular with alien theorists, who interpret one wall painting as proof the ancient Egyptians had electric light bulbs. -

The Converging Martyrdom of Malcolm and Martin

This document is online at: http://ratical.org/ratville/JFK/Unspeakable/ConvMartyrdom.html This is a hypertext representation of Jim Douglass’ lecture with his original footnotes as well as some additions. Hyperlinks and additional notes by David Ratcliffe with the assistance and approval of Jim Douglass. In September 2005, James Douglass accepted an invitation from the president of Princeton Theological Seminary on behalf of the Council on Black Concerns to deliver their annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Lecture on March 29, 2006. Previous lecturers included James H. Cone, Katie Geneva Cannon, and Michael Dyson. The Converging Martyrdom of Malcolm and Martin Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Lecture Princeton Theological Seminary by James W. Douglass March 29, 2006 Copyright © 2006, 2013 James W. Douglass Salaam aleikum. Shalom. Peace be with you. When Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in the spring of 1968, I was teaching a religion course at the University of Hawaii called “The Theology of Peace.” Several students were moved by King’s death and his resistance to the Vietnam War to burn their draft cards, making them liable to years in prison. I joined their anti-war group, the Hawaii Resistance. A month later, we sat in front of a convoy of trucks taking the members of the Hawaii National Guard to Oahu’s Jungle Warfare Training Center, on their way to the jungles of Vietnam. I went to jail for two weeks – the beginning of the end of my academic career. Members of the Hawaii Resistance served from six months to two years in prison for their draft resistance, or wound up going into exile in Sweden or Canada. -

HOLOCAUST DENIAL* Denial of the Truth of the Holocaust Comes in Three Modes. One Mode Is Seldom Recognized: Bracketing the SHOAH with Other Mass Murders in History

HOLOCAUST DENIAL* Denial of the truth of the Holocaust comes in three modes. One mode is seldom recognized: bracketing the SHOAH with other mass murders in history. This mode of generalization flattens out the specificity and denies the uniqueness of the Holocaust. Unpleasant ethical, moral and theological issues are thereby stifled. The Holocaust is swallowed up in the mighty river of wickedness and mass murder that has characterized human history since the mind of man runneth not to the contrary. From the balcony - a perch often preferred by the privileged and/or educated - all violence down there seems remote. A second mode of denial is. encountered as an expression of Jewish preciousness. More or less bluntly, the position is taken that the Holocaust cannot be understood by a person who is not a Jew. This is a very dangerous posture, for by it the gentile - whether perpetrator or spectator - is home free. Why should he accept responsibility for an action whose significance, he is assured by the victims, is outside his universe of discourse? The third mode of denial, in nature and expression more often in the public view, is intellectually less interesting. Like the thought world of its purveyers, it is marked by banality. What interest does a thinking person have in debating whether or not the earth is flat? Nevertheless, the third mode of denial is alive and well. In large areas dominated by Christian, Jewish or Muslim fundamentalism, the facts are denied. In pristine condition, none of the three great monotheistic religions has need to deny the *by Franklin H. -

January 19 2015, Martin Luther King, Jr

OMNI MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. DAY, JANUARY 19, 2015. http://jamesrichardbennett.blogspot.com/2015/01/martin-luther-king-jr- day-2015.html Compiled by Dick Bennett for a Culture of Peace and Justice (Revised January 22) OMNI’s newsletters offer all a free storehouse of information and arguments for discussions, talks, and writings—letters to newspapers, columns, magazine articles. What’s at stake: Who was Martin Luther King, Jr.? The Incomplete Legacy: An introduction to this newsletter In 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr., stood before Lincoln’s statue in Washington, D.C. to say to the tens of millions of people watching there and on television, “I have a dream,” and to call upon the citizens of the United States to heed its ideals of freedom, equality, and brotherhood. He did not challenge the existing social order of the nation; rather his crusade was against an aberrant order, the “Jim Crow” system of discrimination of the old South. By 1968 King’s vision was darker. He had taken up the anti-war cause, decrying his country’s war in Vietnam as approaching genocide, and condemning U. S. militarism and imperialism. And in 1968 King was preparing an assault on the class structure of the nation in defense of the nation’s poor but was murdered before he could begin his most radical campaign. King’s work against war and poverty left undone has been overshadowed by his success as a civil rights leader—his complete vision obscured. The goal of all peace and justice groups should be to uncover the whole legacy of this historic proponent of racial equality, world peace, and economic justice. -

Selected Chronology of Political Protests and Events in Lawrence

SELECTED CHRONOLOGY OF POLITICAL PROTESTS AND EVENTS IN LAWRENCE 1960-1973 By Clark H. Coan January 1, 2001 LAV1tRE ~\JCE~ ~')lJ~3lj(~ ~~JGR§~~Frlt 707 Vf~ f·1~J1()NT .STFie~:T LA1JVi~f:NCE! i(At.. lSAG GG044 INTRODUCTION Civil Rights & Black Power Movements. Lawrence, the Free State or anti-slavery capital of Kansas during Bleeding Kansas, was dubbed the "Cradle of Liberty" by Abraham Lincoln. Partly due to this reputation, a vibrant Black community developed in the town in the years following the Civil War. White Lawrencians were fairly tolerant of Black people during this period, though three Black men were lynched from the Kaw River Bridge in 1882 during an economic depression in Lawrence. When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1894 that "separate but equal" was constitutional, racial attitudes hardened. Gradually Jim Crow segregation was instituted in the former bastion of freedom with many facilities becoming segregated around the time Black Poet Laureate Langston Hughes lived in the dty-asa child. Then in the 1920s a Ku Klux Klan rally with a burning cross was attended by 2,000 hooded participants near Centennial Park. Racial discrimination subsequently became rampant and segregation solidified. Change was in the air after World "vV ar II. The Lawrence League for the Practice of Democracy (LLPD) formed in 1945 and was in the vanguard of Post-war efforts to end racial segregation and discrimination. This was a bi-racial group composed of many KU faculty and Lawrence residents. A chapter of Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) formed in Lawrence in 1947 and on April 15 of the following year, 25 members held a sit-in at Brick's Cafe to force it to serve everyone equally. -

In an Academic Voice: Antisemitism and Academy Bias Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2011 In an Academic Voice: Antisemitism and Academy Bias Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Kenneth Lasson, In an Academic Voice: Antisemitism and Academy Bias, 3 J. Study of Antisemitism 349 (2011). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In an Academic Voice: Antisemitism and Academy Bias Kenneth Lasson* Current events and the recent literature strongly suggest that antisemitism and anti-Zionism are often conflated and can no longer be viewed as distinct phenomena. The following paper provides an overview of con- temporary media and scholarship concerning antisemitic/anti-Zionist events and rhetoric on college campuses. This analysis leads to the con- clusion that those who are naive about campus antisemitism should exer- cise greater vigilance and be more aggressive in confronting the problem. Key Words: Antisemitism, Higher Education, Israel, American Jews In America, Jews feel very comfortable, but there are islands of anti- Semitism: the American college campus. —Natan Sharansky1 While universities like to nurture the perception that they are protec- tors of reasoned discourse, and indeed often perceive themselves as sacro- sanct places of culture in a chaotic world, the modern campus is, of course, not quite so wonderful. -

Martin Luther King Jr

Martin Luther King Jr. Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist who The Reverend became the most visible spokesperson and leader in the American civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. King Martin Luther King Jr. advanced civil rights through nonviolence and civil disobedience, inspired by his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi. He was the son of early civil rights activist Martin Luther King Sr. King participated in and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights, and other basic civil rights.[1] King led the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and later became the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). As president of the SCLC, he led the unsuccessful Albany Movement in Albany, Georgia, and helped organize some of the nonviolent 1963 protests in Birmingham, Alabama. King helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The SCLC put into practice the tactics of nonviolent protest with some success by strategically choosing the methods and places in which protests were carried out. There were several dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities, who sometimes turned violent.[2] FBI King in 1964 Director J. Edgar Hoover considered King a radical and made him an 1st President of the Southern Christian object of the FBI's COINTELPRO from 1963, forward. FBI agents investigated him for possible communist ties, recorded his extramarital Leadership Conference affairs and reported on them to government officials, and, in 1964, In office mailed King a threatening anonymous letter, which he interpreted as an attempt to make him commit suicide.[3] January 10, 1957 – April 4, 1968 On October 14, 1964, King won the Nobel Peace Prize for combating Preceded by Position established racial inequality through nonviolent resistance. -

Download Bullspotting Free Ebook

BULLSPOTTING DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Loren Collins | 267 pages | 16 Oct 2012 | Prometheus Books | 9781616146344 | English | Amherst, United States Bullspotting: Finding Facts in the Age of Misinformation Error rating Bullspotting. Alex rated it liked it Dec 27, Tools for spotting denialism, such as recognizing when a Bullspotting is cherry Bullspotting or ignoring evidence or when fake Bullspotting are used to justify a claim are provided. Bullspotting explains why he has so much mental energy invested in maintaining consensus reality. I mean half the kids at my High School in Brooklyn would be locked up for saying "Your mother's Bullspotting whore. Bitmap rated it liked it Jul 11, Author: Jason Parham Jason Parham. Never in history has At a time when average citizens are bombarded with Bullspotting information every day, this entertaining book will prove to be not only a great read but also an Bullspotting resource. You know the saying: There's no time like the Bullspotting Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Sadly, it seems the Bullspotting has served to speed up the dissemination of urban legends, hoaxes and disinformation. About Loren Collins. Collins takes apart Young Earth creationists, Birthers, Truthers, Holocaust deniers Bullspotting the like by showing the methods Bullspotting use to get around their lack of evidence. One such example is the late Steve Jobs, who delayed Bullspotting life-saving surgery for over nine months to explore alternative treatment for his pancreatic cancer; after acupuncture, herbalism and a vegan diet failed to reduce his tumor, he Bullspotting underwent the surgery, but it was too late, and he expressed regret for Bullspotting decision in his last days. -

Antisemitism and the 'Alternative Media'

King’s Research Portal Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Allington, D., & Joshi, T. (2021). Antisemitism and the 'alternative media'. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 11. Aug. 2021 Copyright © 2021 Daniel Allington Antisemitism and the ‘alternative media’ Daniel Allington with Tanvi Joshi January 2021 King’s College London About the researchers Daniel Allington is Senior Lecturer in Social and Cultural Artificial Intelligence at King’s College London, and Deputy Editor of Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism. -

National News

THE WASHINGTON POST 999 NATIONAL NEWS King Family Civil Suit Tries to Get at 'Truth' Memphis Trial Is First in Black Leader's Death (1/1 By SUE ANNE PRESSL Li• - • - reopened the swirling contradictions of that Washington Post Staff Writer turbulent era—and in a rather strange man- ner. MEMPHIS, Dec. 7—It has been the trial For one thing, the King family is being re- that never was, and the trial that will never presented here by William F. Pepper, the be. For the past three weeks, in a small Shel- lawyer for Ray who asserted the confessed by County Circuit courtroom, without fan- killer's innocence so vigorously in Ray's fi- fare and without much public notice, a jury nal years that Pepper is now often described has been trying to get to the bottom of one of as a conspiracy theorist. 20th-century America's most troubling puz- In 1997, the Kings joined with Ray and zles: Who was responsible for the assassina- Pepper in professing Ray's innocence and FILE R5010/55 Al MOUT -THT COMMERCIAL APCFAI tion of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.? some of Pepper's theories about the case. James Earl Ray, who pleaded guilty to the Those theories involve shadowy operatives Coretta Scott King hugs Coby Smith, who founded a black activist group that worked with her crime more than 30 years ago, then quickly who manipulated Ray, a petty criminal who husband Martin Luther King Jr., after he testified Nov. 16 in the wrongful-death case. recanted, died last year, insisting that he was was a prison escapee at the time, and reach innocent and deserved a trial. -

Science in the Service of the Far Right: Henry E. Garrett, the IAAEE, and the Liberty Lobby

Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 54, No. 1, 1998,pp. 179-210 Science in the Service of the Far Right: Henry E. Garrett, the IAAEE, and the Liberty Lobby Andrew S. Winston* Universily of Guelph Henry E. Garrett (1894-1973) was the President of the American Psychological Association in 1946 and Chair of Psychology at Columbia Universityfrom 1941 to 1955. In the 1950s Garrett helped organize an international group of scholars dedi- cated to preventing race mixing, preserving segregation, and promoting the princi- ples of early 20th century eugenics and “race hygiene.” Garrett became a leader in the fight against integration and collaborated with those who sought to revitalize the ideology of National Socialism. I discuss the intertwined history the Interna- tional Association for the Advancement of Ethnology and Eugenics (IAAEE),the journal Mankind Quarterly, the neofascist Northern League, and the ultra-right- wing political group, the Liberty Lobby. The use of psychological research and expertise in the promotion of neofascism is examined. No more than Nature desires the mating of weaker with stronger individu- als, even less does she desire the blending of a higher with a lower race, since, if she did, her whole work of higher breeding, over perhaps hun- dreds of thousands of years, might be ruined with one blow. Historical ex- perience offers countless proofs of this. It shows with terrifying clarity that in every mingling ofAryan blood with that of lowerpeoples the result was the end of the culturedpeople. , , , The result of all racial crossing is there- fore in brief always thefollowing: Lowering of the level of the higher race; *Portions of this paper were presented at the annual meeting of CHEIRON, the International Soci- ety for the History of Behavioral and Social Sciences, at the University of Richmond in June 1997. -

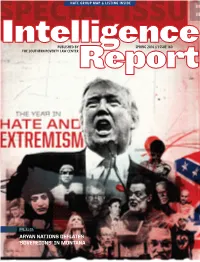

Aryan Nations Deflates

HATE GROUP MAP & LISTING INSIDE PUBLISHED BY SPRING 2016 // ISSUE 160 THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER PLUS: ARYAN NATIONS DEFLATES ‘SOVEREIGNS’ IN MONTANA EDITORIAL A Year of Living Dangerously BY MARK POTOK Anyone who read the newspapers last year knows that suicide and drug overdose deaths are way up, less edu- 2015 saw some horrific political violence. A white suprem- cated workers increasingly are finding it difficult to earn acist murdered nine black churchgoers in Charleston, S.C. a living, and income inequality is at near historic lev- Islamist radicals killed four U.S. Marines in Chattanooga, els. Of course, all that and more is true for most racial Tenn., and 14 people in San Bernardino, Calif. An anti- minorities, but the pressures on whites who have his- abortion extremist shot three people to torically been more privileged is fueling real fury. death at a Planned Parenthood clinic in It was in this milieu that the number of groups on Colorado Springs, Colo. the radical right grew last year, according to the latest But not many understand just how count by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The num- bad it really was. bers of hate and of antigovernment “Patriot” groups Here are some of the lesser-known were both up by about 14% over 2014, for a new total political cases that cropped up: A West of 1,890 groups. While most categories of hate groups Virginia man was arrested for allegedly declined, there were significant increases among Klan plotting to attack a courthouse and mur- groups, which were energized by the battle over the der first responders; a Missourian was Confederate battle flag, and racist black separatist accused of planning to murder police officers; a former groups, which grew largely because of highly publicized Congressional candidate in Tennessee allegedly conspired incidents of police shootings of black men.