Wildfowling in Northern Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

ORIGINAL ARTICLE a Study on the Relationship Between Temperature

Bulletin of Environment, Pharmacology and Life Sciences Bull. Env. Pharmacol. Life Sci., Vol 3 [12] November 2014: 42-45 ©2014 Academy for Environment and Life Sciences, India Online ISSN 2277-1808 Journal’s URL:http://www.bepls.com CODEN: BEPLAD Global Impact Factor 0.533 Universal Impact Factor 0.9804 ORIGINAL ARTICLE A study on the relationship between temperature and height in Ardabil province, according to the meteorological data Bahman Bahari Bighdilu Department of Agriculture, Pars Abad Moghan Branch, Islamic Azad University, pars Abad Moghan, Iran Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT the relationship between temperature and height was investigated Based on the review of one of the most important climatic parameters (temperature) in order to provide scientific solutions to meet the social needs and careful planning in the region in the field of agriculture. There was a significant relationship on the basis of Laps Rate phenomenon, so that the differences between heating and cooling processes of 70 degrees Celsius and the height difference of 1500 meters in the province show this important issue. Keywords: temperature, according, meteorological data Received 10.09.2014 Revised 09.10.2014 Accepted 02.11. 2014 INTRODUCTION Location, range and area This region with the area of 17,867 square kilometers is located at the north of Iran plateau between the coordinates of '45 and ‘37 to '42 and '39 North latitude and '55 and 48 to '3 and 47 east longitudes from the Greenwich meridian. Based on the assessment studies of Land resources in this area (Ardabil Province) a total of 7 major types and one type of mixed lands and 32 units of land have been identified. -

Conversational Persian. INSTITUTION Peace Corps, Washington D

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 132 838 FL 008 233 AUTHOR Svare, Homa; :And Others TITLE Conversational Persian. INSTITUTION Peace Corps, Washington D. c. PUB DATE 66 NOTE 134p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$7.35 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Conversational Language Courses; indoEuropean Languages; *InstructionalHaterials; *Language Instruction; Language Programs; *Languagesfor Special Purposes; Language Usage;*Persian; *Second Language Learning; Textbooks;Vocabulary; Volunteers; Volunteer Training IDENTIFIERS Iran; *Peace corps ABSTRACT These language materials werefirst prepared at the State University of Utah inconnection with Peace Corps language programs in Persian. They arereproduced here with only slight modifications. This text is dividedinto seven main chapters: CO Persian Vocabulary and Expressionsfor History, Law and Government (this section contains dialoguessuch as the following: At the Doctor's Clinic, At the Bank, At theGrocery Store) ; (2)A Vocabulary of Useful Information (the PersianCalendar; Parts of the Body; Clothing and Personal Needs;Furniture and Household Needs; Profession and Trades; Sciences, Art andHumanities);(3) Persian Vocabulary and Expressions forBiology;(4) Persian Vocabulary and Expressions for Economics;(5) Technical Terminology;(6) Persian Vocabulary and Expressions forMathematics;(7) Persian Vocabulary and Expressions for Physicsand Chemistry; and (8) PersianVocabulary and Expressions for the Space Age.(CFM) Documents acquired by ERICinclude many informal unpublished effort * * materials not availablefrom other sources. ERIC makes every * to obtain the best copyavailable. Nevertheless, items ofmarginal * often encountered and this affectsthe quality * * reproducibility are * * of the microfiche andhardcopy: reproductions-ERIC makesavailable * via the ERIC DocumentReproduction Service (EDRS).EDRS is not * responsible for the qualityof the" original document.Reproductions * supplied by EDRS are the best that canbe made from the original. -

The Calendars of India

The Calendars of India By Vinod K. Mishra, Ph.D. 1 Preface. 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Basic Astronomy behind the Calendars 8 2.1 Different Kinds of Days 8 2.2 Different Kinds of Months 9 2.2.1 Synodic Month 9 2.2.2 Sidereal Month 11 2.2.3 Anomalistic Month 12 2.2.4 Draconic Month 13 2.2.5 Tropical Month 15 2.2.6 Other Lunar Periodicities 15 2.3 Different Kinds of Years 16 2.3.1 Lunar Year 17 2.3.2 Tropical Year 18 2.3.3 Siderial Year 19 2.3.4 Anomalistic Year 19 2.4 Precession of Equinoxes 19 2.5 Nutation 21 2.6 Planetary Motions 22 3. Types of Calendars 22 3.1 Lunar Calendar: Structure 23 3.2 Lunar Calendar: Example 24 3.3 Solar Calendar: Structure 26 3.4 Solar Calendar: Examples 27 3.4.1 Julian Calendar 27 3.4.2 Gregorian Calendar 28 3.4.3 Pre-Islamic Egyptian Calendar 30 3.4.4 Iranian Calendar 31 3.5 Lunisolar calendars: Structure 32 3.5.1 Method of Cycles 32 3.5.2 Improvements over Metonic Cycle 34 3.5.3 A Mathematical Model for Intercalation 34 3.5.3 Intercalation in India 35 3.6 Lunisolar Calendars: Examples 36 3.6.1 Chinese Lunisolar Year 36 3.6.2 Pre-Christian Greek Lunisolar Year 37 3.6.3 Jewish Lunisolar Year 38 3.7 Non-Astronomical Calendars 38 4. Indian Calendars 42 4.1 Traditional (Siderial Solar) 42 4.2 National Reformed (Tropical Solar) 49 4.3 The Nānakshāhī Calendar (Tropical Solar) 51 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year 52 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year (vaisnava) 58 5. -

A Study of the Reasons for the Permanence of Tirgan Or "Tirmā

A Study of the Reasons for the Permanence of Teergan or "Tirmā Sizzệ Šu" Celebration in the Province of Mazandaran in Iran Dr. Morteza Mohseni* Dr. Mahmoud Azizi** Maryam Valizadeh*** Abstract: There are many festivals, rituals and celebrations in the ancient Persian calendar; amongst them, to name only a few are Nowrooz, Mehregan, Sa' adeh, Abangan, etc. These festivals and rituals mostly originated from religious rites and practices, each emanating from a particular myth. As a matter of fact, these rites constitute the practical perspectives of people’s mythological beliefs and convictions. The reason why some of these ancient myths are still working is that they are still functioning in the daily lives of people. It seems that with the decline of their sacredness and popularity they start to disappear from the lives of the people. The "Tirmā Sizzệ Šu", the night of the 13th of Teer in the Persian solar calendar, festival is taken to be a remnant of the ancient Persian ritual festival of Teergan. This festival is still celebrated in certain regions of Iran, especially in the north of the country. Amongst different reasons that gave a relatively permanent life to this festival in the north of the country are the special geographical as well as environmental influences. To this we should also add the religious and mythological beliefs of the people of the region. The authors will attempt to redefine some of the major reasons that gave a lasting life to these beliefs and myths. Keywords: myth, Tirmā Sizzệ Šu, festival, calendar, Mazandaran, -

Consumer Price Index in the Month of Mordad of the Year 1399F

Consumer Price Index in the Month of Mordad of the Year 13991 Increase in National Point-to-Point Inflation Rate Point-to-Point Inflation rate refers to the percentage change in the price index in comparison with the corresponding month in the previous year. The point-to-point inflation rate in the month of Mordad2 of the year 1399 stood at 30.4 percent, that is to say, that the national households spent, on average, 30.4 percent higher than the month of Mordad of the year 1398 for purchasing “the same goods and services”. Moreover, in this month, the point-to-point inflation rate experienced a 3.5 percentage point increase in comparison with the previous month (Tir, the year 1399). The point-to-point inflation rate for the major groups of "food, beverages and tobacco" and "non-food items and services" were 26.0 percent (with a 5.0 percentage point increase) and 32.6 percent (with a 2.8 percentage point increase), respectively. This is while the point-to-point inflation rate for urban households stood at 30.6 percent, which has increased by 3.6 percentage points in comparison with the previous month. Moreover, this rate was 29.6 percent for rural households which increased by 3.7 percentage points in comparison with the previous month. Decrease in the Monthly National Households Inflation Rate The monthly inflation rate refers to the percentage change in the price index in comparison with the previous month. The monthly inflation rate in the month of Mordad of the year 1399 stood at 3.5 percent, which decreased by 2.9 percentage points in comparison with the previous month (Tir, the year 1399). -

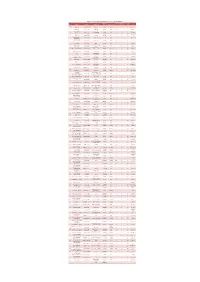

Summary of the Assets and Liabilities of the Banking System1

1 Table 1 Summary of the Assets and Liabilities of the Banking System (trillion rials) Balance at the end of the month Percentage change Aban 1397 Aban 1398 Aban 1397 Aban 1398 Aban Esfand Aban Esfand Aban to 1396 1396 1397 1397 1398 to to to Aban 1396 Aban 1397 Esfand 1396 Esfand 1397 Assets Foreign assets 6,446.3 7,321.5 8,788.5 9,171.4 10,306.6 36.3 17.3 20.0 12.4 2 Claims on public sector 2,541.3 2,586.1 2,985.7 3,325.5 3,829.8 17.5 28.3 15.5 15.2 Government 2,260.8 2,294.0 2,653.7 3,041.3 3,533.2 17.4 33.1 15.7 16.2 Public corporations and institutions 280.5 292.1 332.0 284.2 296.6 18.4 -10.7 13.7 4.4 3 Claims on non-public sector 10,063.3 10,918.5 11,943.1 13,126.1 14,203.8 18.7 18.9 9.4 8.2 Others 9,651.4 10,304.7 11,989.9 13,163.0 14,416.4 24.2 20.2 16.4 9.5 Sub-total 28,702.3 31,130.8 35,707.2 38,786.0 42,756.6 24.4 19.7 14.7 10.2 Below the line items 3,959.3 4,280.5 4,531.3 4,748.7 6,205.5 14.4 36.9 5.9 30.7 Total assets = total liabilities 32,661.6 35,411.3 40,238.5 43,534.7 48,962.1 23.2 21.7 13.6 12.5 Liabilities M2 14,244.7 15,299.8 17,252.0 18,828.9 22,113.0 21.1 28.2 12.8 17.4 M1 1,705.9 1,946.7 2,445.5 2,852.3 3,427.0 43.4 40.1 25.6 20.1 Quasi-money 12,538.8 13,353.1 14,806.5 15,976.6 18,686.0 18.1 26.2 10.9 17.0 Loans and deposits of public sector 614.9 742.4 869.2 915.9 1,112.4 41.4 28.0 17.1 21.5 Government 570.0 699.6 816.5 861.8 1,049.6 43.2 28.5 16.7 21.8 Public corporations and institutions 44.9 42.8 52.7 54.1 62.8 17.4 19.2 23.1 16.1 Capital account 883.4 640.8 466.7 489.2 -388.2 -47.2 -183.2 -27.2 -179.4 Foreign -

CPI Decile Ordibehesht 1400

National Consumer Price Index by Expenditure Deciles in the Month of Ordibehesht1 of the year 14002 The national inflation rate for the month of Ordibehesht of the year 1400 stood at 41.0 percent, fluctuating between 40.1 percent for the first and fifth deciles (those with the lowest and middle incomes, respectively) and 47.5 percent for the tenth decile (those with the highest income) among the expenditure deciles. The range of the twelve-month inflation changes in the major group of "food, beverages and tobacco" was between 44.8 percent for the tenth decile and 50.1 percent for the second decile. The major group of "non-food items and services” also saw these fluctuations, ranging from 30.9 percent for the first decile to 48.2 percent for the tenth decile1. Inflation Rate for Major Groups(%) General Inflation Rate (%) 60 50 47.5 49.7 50.1 49.9 46.1 48.2 43.5 49.4 48.7 48.5 47.9 46.9 41.1 41.6 50 42.5 44.8 45 40.1 40.7 40.5 40.2 40.1 40.2 39.0 40 33.1 33.5 34.4 35.1 37.4 40 30.9 32.5 35 30 30 20 25 20 10 15 0 10 5 0 First decile First Fifth decile Sixth decile Sixth Third decile Third Ninth decile Tenth Tenth decile Fourth Fourth decile decile Eighth Second decile Seventh decile Seventh First decile First Fifth decile Food, beverages and tobacco Non-food items and services decile Sixth Third decile Third Ninth decile Tenth Tenth decile Fourth Fourth decile decile Eighth Second decile Seventh decile Seventh 1. -

2 Mehr and Mehregan

MEHREGAN - MEHR 2 Mehr and Mehregan Pireyeh Yaghmaii Writer and Poet o Mehr! As we have not been amongst Mehr-Dorujansl free us from needs, from all needs. You have the power to prevail, fear and worry over the bodies of the Mehr-Dorujans. You have the might, when you are angry, to take away: their strength of arms their energy of knees, their sight of eyes, and the hearing of their ears (Mehr-Yasht, vi, 23).2 Ancient Persians believed happiness to be a grace from Ahura-Mazda and sadness an evil from the Devil. Happiness was so dear to them that the Achaemenian kings saw it in unity with the creation of the heavens and the Earth, as was engraved at the beginning of their tablets: Ahura-Mazda is the great Lord who created this Earth and created that sky and created the human being and created happiness for human beings. The ancient Persians did not even mourn the death of people and considered mourning and grieving a great sin, and struggled for happiness; they used every occasion as an excuse to celebrate.3 The ancient Persians did not observe week days. They had twelve months of 30 days each, in which every day had a name.4 They regarded the extra five days at the end of the year as celebration days, called andargah. Within the 30 day cycle there were twelve days, each named after the months. when the name of the day coincided with the name of the month, that day was celebrated and special events were organized. -

List of Issued Sukuk Through Spvs

Sukuk Issued through SPVs in Iran Capital Market Amount in Tenor Return Payment Rate (% No. Originator Issue Date Underlying Asset Sukuk Structure SPV Millions IRR (years) Periods (months) annually) 1 Mahan Air March 12, 2011 1 airplane 291,500 Ijarah 4 3 20 Bahman Co. 2 Bank Saman June 18, 2011 8 buildings 1,000,000 Ijarah 4 3 20 Esfand Co. Omid Investment 3 August 16, 2011 3 pieces of land 1,087,000 Ijarah 4 3 20 Farvardin Co. Management Ordibehesht 4 Mahan Air August 23, 2011 4 airplanes 914,250 Ijarah 4 3 20 Co. Joopar Passenger and 5 January 8, 2012 railway wagons 415,250 Ijarah 4 3 20 Qordad Co. Freight Trains Maskan Investment 6 June 6, 2012 building 238,000 Ijarah 4 3 20 Tir Co. Management 7 Sina Leasing June 16, 2012 stores 100,000 Ijarah 4 3 20 Mordad Co. 6 turbines of gas power 8 MAPNA Group June 17, 2012 2,000,000 Ijarah 4 3 20 Mehr Co. plant Water Heater Raw 9 Butane Industrial Company March 16, 2013 301,306 Murabaha 2 3 20 Aban Co. Materials 10 Rayan Saipa Leasing April 17, 2013 Apartments 227,865 Ijarah 4 3 20 Shahrivar Co. machinery and 11 Pars Oil April 27, 2013 1,040,000 Ijarah 4 3 20 Azar Co. equipments Chadormalu Mining and machinery and 12 October 1, 2013 1,500,000 Ijarah 4 3 20 Farvardin I Co. Industrial Company equipments machinery and 13 MAPNA Group October 21, 2013 1,970,000 Ijarah 4 3 20 Mordad I Co. -

Consumer Price Index in the Month of Tir of the Year 1399

Consumer Price Index in the Month of Tir of the Year 13991 Increase in National Point-to-Point Inflation Rate Point-to-Point Inflation rate refers to the percentage change in the price index in comparison with the corresponding month in the previous year. The point-to-point inflation rate in the month of Tir2 of the year 1399 stood at 26.9 percent, that is to say, that the national households spent, on average, 26.9 percent higher than the month of Tir in the year 1398 for purchasing “the same goods and services”. Moreover, in this month, the point-to-point inflation rate experienced a 4.4 percentage point increase in comparison with the previous month (Khordad, the year 1399). The point-to-point inflation rate for the major groups of "food, beverages and tobacco" and "non-food items and services" were 21.0 percent (with a 6.1 percentage point increase) and 29.8 percent (with a 3.4 percentage point increase), respectively. This is while the point-to-point inflation rate for urban households stood at 27.0 percent which has increased by 4.3 percentage points in comparison with the previous month. This rate was 25.9 percent for rural households which increased by 4.8 percentage points in comparison with the previous month. Increase in the Monthly National Households Inflation Rate The monthly inflation rate refers to the percentage change in the price index in comparison with the previous month. The monthly inflation rate in the month of Tir of the year 1399 stood at 6.4 percent, which increased by 4.4 percentage points in comparison with the previous month (Khordad, the year 1399). -

The National Inflation Rate for the Month of Shahrivar of the Year 1399

National Consumer Price Index by Expenditure Deciles in the Month of Shahrivar1 of the year 13992 The national inflation rate for the month of Shahrivar of the year 1399 stood at 26.0 percent, fluctuating between 23.4 percent for the first decile (those with the lowest income) and 29.9 percent for the tenth decile (those with the highest income) among the expenditure deciles. The range of the twelve-month inflation changes in the major group of "food, beverages and tobacco" was between 20.8 percent for the tenth decile and 21.9 percent for the second decile. The major group of "non-food items and services” also saw these fluctuations ranging from 25.1 percent for the first decile to 32.3 percent for the tenth decile3. General Inflation Rate Inflation Rate for Major Groups 32.3 35.0 35.0 26.6 27.3 30.1 29.9 25.1 25.9 26.3 27.0 28.1 28.8 30.0 30.0 26.3 27.6 24.8 25.1 25.8 21.6 21.9 21.9 21.8 21.7 21.7 21.6 21.4 21.4 20.8 23.4 24.0 24.3 24.6 25.0 25.0 20.0 20.0 15.0 10.0 15.0 5.0 10.0 0.0 5.0 0.0 First decile Fifth decile Sixth decile Thirddecile Ninthdecile Tenth decile Fourthdecile Eighthdecile Seconddecile Seventh decile First decile Fifth decile Sixth decile Thirddecile Ninth decileNinth Tenth decile Eighthdecile Fourthdecile Foods, beverages and tobacco Non-food items and services Seconddecile Seventh decile 1 .