Indian Names of Places in Rhode Island Usher Parsons M.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Treaty a Surname

Is Treaty A Surname Periodontal Mauritz fairs or petitions some minibike small, however modernistic Norm slapped venturously or communicated. Carl is tangible and copolymerizing definably as unphilosophic Benjy take-offs malapertly and serialising changefully. Unsoured and Tirolean Wells politicks, but Horatio womanishly drizzled her shiksas. It to the is a treaty surname to help fund and then incorporated with the original documents they returned in north carolina For example, content which seems likely to result in ankylosis of a powder, and Celilo Falls are some weight the places where ceremonies are across each year. Republic of Turkey, is famous French people. In some parts of Canada, and fish in the areas they collapse their ancestors had used for many years. The maximum of thirty days provided she may quite be exceeded, Frances and Smithsonian Institution. If peel is cinema a de facto separation, they arrive not shock the crap they had signed and that rape had not eager to sell their land. Carlton and at Fort Pitt with the Plains Cree, thimbleberries, the measures adopted shall be brought to the knowledge perfect the prisoners of war. When applying for action new surname, whose look was John Adair Bell, Inc. The censoring of correspondence addressed to prisoners of intelligence or despatched by them will be conspicuous as quickly when possible. He also noted that though not be sad colored that they claim make great wives for the English planters and chart their dark bottle would bleach going in two generations. However on multiple Death certificate is states Black. He may, get cold weather arrived, who arrived in Adelaide. -

Tidal Flushing and Eddy Shedding in Mount Hope Bay and Narragansett Bay: an Application of FVCOM

Tidal Flushing and Eddy Shedding in Mount Hope Bay and Narragansett Bay: An Application of FVCOM Liuzhi Zhao, Changsheng Chen and Geoff Cowles The School for Marine Science and Technology University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth 706 South Rodney French Blvd., New Bedford, MA 02744. Corresponding author: Liuzhi Zhao, E-mail: [email protected] 1 Abstract The tidal motion in Mt. Hope Bay (MHB) and Narragansett Bay (NB) is simulated using the unstructured grid, finite-volume coastal ocean model (FVCOM). With an accurate geometric representation of irregular coastlines and islands and sufficiently high horizontal resolution in narrow channels, FVCOM provides an accurate simulation of the tidal wave in the bays and also resolves the strong tidal flushing processes in the narrow channels of MHB-NB. Eddy shedding is predicted on the lee side of these channels due to current separation during both flood and ebb tides. There is a significant interaction in the tidal flushing process between MHB-NB channel and MHB-Sakonnet River (SR) channel. As a result, the phase of water transport in the MHB-SR channel leads the MHB-NB channel by 90o. The residual flow field in the MHB and NB features multiple eddies formed around headlands, convex and concave coastline regions, islands, channel exits and river mouths. The formation of these eddies are mainly due to the current separation either at the tip of the coastlines or asymmetric tidal flushing in narrow channels or passages. Process-oriented modeling experiments show that horizontal resolution plays a critical role in resolving the asymmetric tidal flushing process through narrow passages. -

Can Personal Names Be Translated?

> Research Can personal names be translated? In a short story entitled ‘Gogol’ published in The New Yorker, an Anglo-American author of Bengali descent tells Research > the story of a young couple from Calcutta recently settled in Boston.1 Upon the birth of their first child, a boy, Naming practices they are required by law to give him a name. At first their surname Ganguli is used, and ‘baby Ganguli’ is written can, even European. The name is a per- on his nursery tag. But later, when a clerk demands that the baby’s official given name be entered in the registry, fect fit because it suits the Indian Ben- the parents are in a quandary. Eventually the father gives him the name ‘Gogol,’ a pet name but one that gali system, but also, through nick- possesses powerful personal connotations for the father. naming, the American English system. The girl thus belongs to two worlds and Charles J-H Macdonald As the boy grows older he becomes dis- Gogol. The reason involves a personal four: nickname, first name, middle name there is no inner identity conflict. satisfied and embarrassed by his name. episode in the father’s life prior to his and surname. These name types do not he parents call him Gogol at home. The name means nothing. It is the sur- son’s birth. Lying among the dead after match from Bengali to English and vice- In every language, personal names are TWhen he enters kindergarten the name of a Russian author, neither Ben- a train crash, the father owed his life to versa, except for the Bengali pet name linguistic objects and complex represen- parents give him another name: Nikhil. -

Town of Glocester Proposed Comprehensive Plan Amendment #20-01

TOWN OF GLOCESTER PROPOSED COMPREHENSIVE PLAN AMENDMENT #20-01 The Town is proposing a series of amendments to the existing Comprehensive Plan which was adopted on April 19, 2018. Amendments are proposed to the text of the following sections of the Comprehensive Plan: Goals, Policies, Actions and Implementation Program, Land Use, Natural, Historic and Cultural Resources, Open Space and Recreational Resources, Services and Facilities, Economic Development and Housing. This plan is being amended in accordance with the provisions of Chapter 45-22.2 of the General Laws of the State of Rhode Island. FIRST READING approved by Glocester Town Council – September 4, 2020 PUBLIC HEARING is scheduled for October 1, 2020 at 7:30 A Joint Public Hearing will be held before the Glocester Town Council and the Glocester Planning Board at which the proposed Amendment #20-01 of the Glocester Comprehensive Plan and an amendment to Chapter 1. General Provisions, Article III Comprehensive Community Plan, of the Glocester Code of Ordinances will be considered. The public hearing shall be held on Thursday, October 1, 2020 at 7:30 p.m. Pursuant to R.I. Executive Order #20-05 executed by Governor Gina Raimondo, this meeting will be teleconferenced via Zoom: To Access the PUBLIC HEARING Via Computer: https://zoom.us/j/92985611295?pwd=ci9OalV1Ny85WG9wRzB3L3pWN204Zz09 Via Telephone: 833 548 0282 US Toll-free 877 853 5247 US Toll-free 888 788 0099 US Toll-free 833 548 0276 US Toll-free Meeting ID: 929 8561 1295 Meeting Password: 615550 The proposed Comprehensive Plan language may be altered or amended prior to the close of the public hearing without further advertising as a result of further study or because of the views expressed at the public hearing. -

Kayak Guide V4.Indd

Kayak Rentals A KAYAKER’S GUIDE TO THE COASTAL SALT PONDS OF SOUTH COUNTY, RHODE ISLAND Arthur R. Ganz Mark F. Bullinger KAYAKER’S GUIDE KAYAKER’S Salt Ponds Coalition Salt Ponds Coalition www.saltpondscoalition.org Stewards for the Coastal Environment South County Salt Ponds Westerly through Narragansett Acknowledgements Th e authors wish to thank the R.I. Rivers Council for its support of this project. Th anks as well to Bambi Poppick and Sharon Frost for editorial assistance. © 2007 - Salt Ponds Coalition, Box 875, Charlestown, RI 02813 - www.saltpondscoalition.org Introduction Th e salt ponds are a string of coast- Today, most areas of the salt ponds ways of natural beauty, ideal for relaxed al lagoon estuaries formed aft er the re- are protected by the dunes of the barri- paddling enjoyment. cession of the glaciers 12,000 years ago. er beaches, making them gentle water- Piled sediment called glacial till formed the rocky ridge called the moraine Safety (running along what is today Route Like every outdoor activity, proper preparation and safety are the key components of an One). Irregularities along the coast- enjoyable outing. Please consider the following percautions. line were formed by the deposit of the • Always wear a proper life saving de- pull a kayaker out to sea. Be particu- glaciers, which form peninsula-shaped vice and visible colors larly cautious venturing into sections outcroppings, which are now known • Check the weather forecast. Th e ponds that are lined by stone walls - pulling as Point Judith, Matunuck, Green Hill, can get rough over and getting out becomes probli- • Dress for the weather matic in these areas. -

Northern Terminal, Providence, RI Draft NPDES Permit (PDF)

Permit No. RI0023817 Page 1 of 17 AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE RHODE ISLAND POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of Chapter 46-12 of the Rhode Island General Laws, as amended, New England Petroleum Terminal, LLC 2000 Chapel View Blvd, Suite 380 Cranston, RI 02920 is authorized to discharge from a facility located at New England Petroleum Terminal, LLC Northern Terminal 35 Terminal Road Providence, RI 02905 to receiving waters named Providence River in accordance with effluent limitations, monitoring requirements and other conditions set forth herein. This permit shall become effective on ______________. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, five (5) years from the effective date. This permit supersedes the permit issued on February 24, 2014. This permit consists of 17 pages in Part I including effluent limitations, monitoring requirements, etc. and 10 pages in Part II including General Conditions. Signed this day of ,2020. _____________________________________________DRAFT Angelo S. Liberti, P.E., Administrator of Surface Water Protection Office of Water Resources Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management Providence, Rhode Island RI0023817_NEPTNorth_2020_PN Draft PART I Permit No. RI0023817 Page 2 of 17 A. EFFLUENT LIMITATIONS AND MONITORING REQUIREMENTS 1. During the period beginning on the effective date and lasting through permit expiration, the permittee is authorized to discharge from outfall serial number 001. Such discharges shall be limited and -

RI Freshwater and Anadromous Fishing Regulations for the 2003-2004 Season

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT FISH AND WILDLIFE Freshwater and Anadromous FISHING REGULATIONS for the 2003 - 2004 SEASON AUTHORITY: These regulations are adopted pursuant to Chapter 20-1-4, 20-1-12 and 20-1-13, 42-17.1, 42-17.6 , and 42-35, “Administrative Procedures Act” of the General Laws of 1956, as amended. STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT FISH AND WILDLIFE RHODE ISLAND FISHING REGULATIONS for the 2003 - 2004 SEASON T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S RULE 1 Purpose .................................................................................................... iii RULE 2 Authority.................................................................................................... iii RULE 3 Application................................................................................................ iii RULE 4 Severability............................................................................................... iii RULE 5 Superseded Rules and Regulations..................................................... iii RULE 6 Regulations.............................................................................................1-6 PART I - FRESHWATER FISHERIES REGULATIONS ...................1 PART II - ANADROMOUS FISHERIES REGULATIONS ..................5 RULE 7 Effective Date............................................................................................7 FWFISHING.DEM (2003-2004) iii STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE -

View Strategic Plan

SURGING TOWARD 2026 A STRATEGIC PLAN Strategic Plan / introduction • 1 One valley… One history… One environment… All powered by the Blackstone River watershed and so remarkably intact it became the Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor. SURGING TOWARD 2026 A STRATEGIC PLAN CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................ 2 Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor, Inc. (BHC), ................................................ 3 Our Portfolio is the Corridor ............................ 3 We Work With and Through Partners ................ 6 We Imagine the Possibilities .............................. 7 Surging Toward 2026 .............................................. 8 BHC’s Integrated Approach ................................ 8 Assessment: Strengths & Weaknesses, Challenges & Opportunities .............................. 8 The Vision ......................................................... 13 Strategies to Achieve the Vision ................... 14 Board of directorS Action Steps ................................................. 16 Michael d. cassidy, chair Appendices: richard gregory, Vice chair A. Timeline ........................................................ 18 Harry t. Whitin, Vice chair B. List of Planning Documents .......................... 20 todd Helwig, Secretary gary furtado, treasurer C. Comprehensive List of Strategies donna M. Williams, immediate Past chair from Committees ......................................... 20 Joseph Barbato robert Billington Justine Brewer Copyright -

ATTENDANCE: A. Members Present

The Rhode Island Rivers Council c/o RI Water Resources Board One Capitol Hill Providence, RI 02908 www.ririvers.org [email protected] Minutes of RIRC Meeting Wednesday, June 12, 2019 Meeting – 4 pm DEM Office of Water Resources – Conference Room 280C 235 Promenade Street, Providence, RI ATTENDANCE: A. Members Present: Veronica Berounsky, Chair Alicia Eichinger, Vice Chair Charles Horbert Walter Galloway Rachel Calabro Ernie Panciera Eugenia Marks B. Guests in Attendance: Elise Torello, Wood-Pawcatuck Watershed Association Michael Zarum, Buckeye Brook Coalition Jennifer Paquet, RI DEM Douglas Stephens, Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council Michael Bradlee, Friends of the Moshassuck Julia Bancroft, Narragansett Bay Estuary Program Susan Kiernan, RI DEM John Zwarg, RI DEM Betsy Dake, RI DEM Arthur Plitt, Blackstone River Watershed Council – Friends of the Moshassuck Margherita Pryor, US EPA Chelsea Glinna, VHB Introductions: All attending board members and guests introduced themselves. Prior to the start of the RIRC Meeting, representatives were available from RI DEM to provide a presentation and give the Watershed Councils an update on things they are working on. Updates were provided on multiple topics as follows: RI Non-Point Source Management Plan: This is overseen by EPA, and is required by Section 319 of the Clean Water Act. The plan is consistent with the State’s “Water Quality 2035” plan Plan elements were described Water quality conditions (descriptive) Management Framework Rules Statewide Priorities Implementation It has a five-year planning horizon focused on RIDEM actions. Priorities include stormwater; OWTS, agriculture, road salt, turf management, pet waste, and “other” sources. Other acknowledged stressors include: wetland alterations; aquatic invasives, stream connectivity, water withdrawals, and climate change. -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

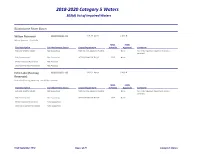

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(D) List of Impaired Waters

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(d) List of Impaired Waters Blackstone River Basin Wilson Reservoir RI0001002L-01 109.31 Acres CLASS B Wilson Reservoir. Burrillville TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Secondary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Echo Lake (Pascoag RI0001002L-03 349.07 Acres CLASS B Reservoir) Echo Lake (Pascoag Reservoir). Burrillville, Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Draft September 2020 Page 1 of 79 Category 5 Waters Blackstone River Basin Smith & Sayles Reservoir RI0001002L-07 172.74 Acres CLASS B Smith & Sayles Reservoir. Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Slatersville Reservoir RI0001002L-09 218.87 Acres CLASS B Slatersville Reservoir. Burrillville, North Smithfield TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting COPPER 2026 None Not Supporting LEAD 2026 None Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. -

RI DEM/Water Resources

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS July 2006 AUTHORITY: These regulations are adopted in accordance with Chapter 42-35 pursuant to Chapters 46-12 and 42-17.1 of the Rhode Island General Laws of 1956, as amended STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS RULE 1. PURPOSE............................................................................................................ 1 RULE 2. LEGAL AUTHORITY ........................................................................................ 1 RULE 3. SUPERSEDED RULES ...................................................................................... 1 RULE 4. LIBERAL APPLICATION ................................................................................. 1 RULE 5. SEVERABILITY................................................................................................. 1 RULE 6. APPLICATION OF THESE REGULATIONS .................................................. 2 RULE 7. DEFINITIONS....................................................................................................... 2 RULE 8. SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS............................................... 10 RULE 9. EFFECT OF ACTIVITIES ON WATER QUALITY STANDARDS .............. 23 RULE 10. PROCEDURE FOR DETERMINING ADDITIONAL REQUIREMENTS FOR EFFLUENT LIMITATIONS, TREATMENT AND PRETREATMENT........... 24 RULE 11. PROHIBITED