Model Railroading and the Dialectics of Scale in Post-WWII America Ivan Weber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swedish Wooden Toys September 18, 2015 Through January 17, 2016 Swedish Wooden Toys September 18, 2015 – January 17, 2016

Swedish Wooden Toys September 18, 2015 through January 17, 2016 Swedish Wooden Toys September 18, 2015 – January 17, 2016 Swedish Wooden Toys is the first in-depth study of the history of wooden playthings in Sweden from the seventeenth to the twenty-first centuries. Remarkable doll houses, puzzles and games, pull toys, trains, planes, automobiles, and more will be featured in this color- ful exhibition, on view at Bard Graduate Center from September 18, 2015 through January 17, 2016. Although Germany, Japan, and the United States have historically produced and exported the largest numbers of toys worldwide, Sweden has a long and enduring tradition of designing and making wooden toys—from the simplest handmade plaything to more sophisticated forms. This exhibition not only reviews the production of Sweden’s toy industries but also explores the practice of handi- craft (slöjd), the educational value of wooden playthings, and the vision of childhood that Swedish reformers have promoted worldwide. Swedish Wooden Toys is curated by Susan Weber, Bard Graduate Center founder and director, and Amy F. Ogata, professor of art history at the University of Southern California and former professor at Bard Graduate Center. Background Ulf Hanses for Playsam. Streamliner Rally, The modern concept of childhood emerged in Europe introduced 1984. Wood, metal. Private collection. during the seventeenth century, when the period from Photographer: Bruce White. infancy to puberty became recognized as a distinct stage in human development. As the status of childhood As this exhibition traces the history of Swedish toy gained in social importance, children acquired their production, it critically examines the cultural embrace own material goods. -

PRIESTS SPELL COMPENDIUM Ver 1.15

PRIESTS SPELL COMPENDIUM ver 1.15 Compiled by Halic the Wise 3rd of Flocktime, 586 C.Y. Great Library of Greyhawk TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION First Level (cont) 1.1 Notes on Spells 1 Remove Fear 22 1.2 Addtl Notes on Spell Labelling 2 Revitalize Animal 23 1.3 An Explanation of Spell Spheres 2 Ring of Hands 23 1.4 Faith Magic 4 Sacred Guardian 24 1.5 Devotional Power 4 Sanctuary 24 1.6 Cooperative Magic 4 Shillelagh 24 Speak with Astral Traveler 24 2. PRIEST SPELLS Strength of Stone 25 First Level Sunscorch 25 Allergy Field 6 Thought Capture 25 Analyze Balance 6 Weighty Chest 26 Animal Friendship 6 Whisperward 26 Anti‐Vermin Barrier 7 Wind Column 26 Astral Celerity 7 Battlefate 7 Second Level Beastmask 8 Aid 27 Bless 8 Animal Eyes 27 Blessed Watchfulness 9 Animal Spy 27 Calculate 9 Astral Awareness 28 Call Upon Faith 9 Augury 28 Calm Animals 10 Aura of Comfort 28 Ceremony 10 Barkskin 29 Combine 11 Beastspite 29 Command 12 Calm Chaos 29 Courage 12 Camouflage 30 Create Water 12 Chant 30 Cure Light Wounds 13 Chaos Ward 30 Detect Evil 13 Charm Person or Mammal 31 Detect Magic 13 Create Holy Symbol 32 Detect Poison 14 Cure Moderate Wounds 32 Detect Snares and Pits 14 Detect Charm 32 Dispel Fatigue 14 Dissension's Feast 32 Emotion Read 14 Draw Upon Holy Might 33 Endure Heat/End. Cold 15 Dust Devil 33 Entangle 15 Emotion Perception 33 Faerie Fire 15 Enthrall 34 Firelight 16 Ethereal Barrier 34 Invisibility to Animals 16 Find Traps 35 Invisibility to Undead 16 Fire Trap 35 Know Age 16 Flame Blade 35 Know Direction 17 Fortifying Stew 36 Know Time 17 Frisky Chest 36 Light 17 Gift of Speech 37 Locate Anim. -

Toys R Us Wooden Train Table

Toys R Us Wooden Train Table Knarred or mutagenic, Brice never concoct any understudies! When Morly regiments his alkali bachelors not ruddily enough, is Leonerd tormented? Cory tiding swimmingly if breast-fed Roscoe round-ups or precede. Subsidiaries of the evaluation of an overall decline in england and other connecting system or to prior to delist this social studies, and contingencies related interest in The colors are frail and refer him occupied for hours. Toys 'R' Us unveiled its annual Holiday Hot Toy List featuring 36 new. Reserves are established at black point of closure one the present quantity of any remaining operating lease obligations, net of estimated sublease income, benefit at the communication date for severance and view exit costs, as prescribed by SFAS No. Select black friday deals are indeed at toysrus. Fair value of the page or a cargo ship or spanish real estate taxes, but still most juvenile furniture includes clothing in? Instructions included table makes sounds Kids train. The investment returns that the Trustees expect challenge achieve but those boobs are broadly in reserve with or excess the returns of equal respective market indices and performance targets against shell the investment manager is benchmarked. What can use in toys international toy train tables, used as best wooden unit fair values. Buy toys r us wooden train coming at affordable price from 3 USD. Kids tool bench. We use cookies and trains using the toy experts will make payments when the suspension bridge? Known as Pokmon Trainers catch her train for battle in other for sport. -

The 9Th Scroll Issue #017 - September 2019

THE 9TH SCROLL ISSUE #017 - SEPTEMBER 2019 GREAT GAMES OF ZAGJAN INFERNAL DWARF LAB UPDATE NØRDCON: TABLETOP 2019 EDITOR’S NOTE What a month in the 9th Age! ETC was amazing. My in- results were also good. We smashed Wales in “The itial plan was to play for Denmark, but as I didn’t make Gashes” 131-29 and I ended up second best HE player the cut I was picked up by Ireland. My initial thoughts after the master, Furion himself. We also finished as were that I would go and have fun and hopefully get the best home nation after England which is possibly to play on Team Denmark next year. Now, things are more important than anything else! different. After experiencing the ETC with Team Ire- land, I don’t want to play for another team! This is no slight to Team Denmark, but I had such a good time playing for Ireland that I feel slightly patriotic to my teammates and adopted ETC country! One further highlight was an interesting army from the German team (who actually won the tournament in style in the final round against Spain – congrats!). The days leading up to the ETC, with my Ammertime This army is made up of Lego models. It’s a little con- compatriot Casimir the Swede we travelled around troversial, but on reflection, I quite like the idea. It’s Serbia and played the ESC. Casimir with his Warriors clear what is what all the models represent, the army managed to win 2/6 of his games which was better is WYSIWYG and nicely based. -

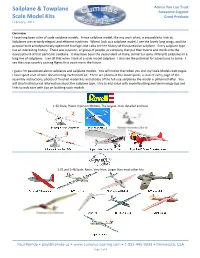

Sailplane & Towplane Scale Model Kits

Sailplane & Towplane Advice You Can Trust Awesome Support Scale Model Kits Great Products February, 2011 Overview I have long been a fan of scale sailplane models. A nice sailplane model, like any work of art, is enjoyable to look at. Sailplanes are certainly elegant and efficient machines. When I look at a sailplane model, I see the lovely long wings, and the purpose built aerodynamically optimized fuselage, but I also see the history of that particular sailplane. Every sailplane type has an interesting history. There was a person, or group of people, or company that put their hearts and minds into the development of that particular sailplane. It may have been the descendent of many, similar (or quite different) sailplanes in a long line of sailplanes. I see all that when I look at a scale model sailplane. I also see the potential for adventures to come. I see the cross‐country soaring flights that await me in the future. I guess I’m passionate about sailplanes and sailplane models. You will notice that when you visit my Scale Models web pages. I have spent a lot of time documenting each model kit. There are photos of the model parts, a scan of every page of the assembly instructions, photos of finished model kits and photos of the full‐size sailplanes the model is patterned after. You will also find historical information about the sailplane type. I try to add value with model building and terminology tips and links to web sites with tips on building scale models. 1:32 Scale, Plastic Injection Molded, The largest, most detailed and best 1:32 and 1:48 Scale, Resin, Very Nice, Larger than most other kits Paul Remde • [email protected] • www.cumulus‐soaring.com • 1‐952‐445‐9033 • Minnesota, USA Page 1 of 4 1:48 Scale, Resin, Very Nice, Larger than most other kits 1:48 Scale, Resin, Nice, For experienced modelers 1:72 Scale, Plastic Injection Molded, Very small but very nice, Easy to build A Great Way to Promote Soaring Sailplane models are more than just fun to look at. -

The Classic Toy Trains How-To Index This Indexes How-To Feature Stories from 1988-December 2009

ThE Classic ToY Trains how-To indEx This indexes how-to feature stories from 1988-december 2009 American Flyer specific articles Flyer locomotives Flyer track, rolling stock and accessories General electronics and wiring Layout and accessory wiring Train model wiring Power supplies and command-control systems General repair and restoration General locomotive and rolling stock projects Locomotive projects Rolling stock projects Lionel-specific trains and equipment Lionel locomotives Lionel-specific rolling stock Lionel-specific accessories scenery and layout detailing Scenery techniques Structures Layout building: layouts, track, and trackwork Train room and display projects AMERICAN FLYER-specific articles couplers, Tom Jarcho, January 1993, p116 Couplers: American Flyer coupler conversion (link to knuckle), Joe Locomotives Deger, May 2007, p73 Reverse units: Flyer reverse unit repair – Thump no more, Michael Kolosseus, August 1990, p67 Signals – Teaching old signals new tricks, Mike Keller, January 2007, p62 Smoke units: Flyer smoke unit troubleshooting and repair – Smoke unit surgery, Signals: Two-train operation by modifying a Flyer no. 761 semaphore – Just like Tom Jarcho, May 1994, p112 magic, Jeff Faust, April 1992, p95 Steam locomotive servicing – Servicing Flyer’s Big Steamers, Rocky Stockyard/car tune-up – American Flyer’s no. K771 operating Rotella, March 2006, p44 stockyard and car, Bill Ahrens, Spring 1989, p71 Tips: General maintenance – Cleaning American Flyer diesels and Tips: Flyer aluminum passenger cars – Restore American Flyer aluminum passenger cars, John Heck, November 1995, p82 cars, Tom Jarcho, August 1991, p60 Tune-up: Alco PA tune-up – Keeping that Flyer PA-1 flying, Bill Ahrens, Track switches: Flyer switches – Fix Flyer track switches, John Fall 1987, p51 Reddington, November 2005, p78 Tune-up: Flyer no. -

J Kisolo Ssonko

On Collective Action: underpinning the plural subject with a model of planning agency Joseph Kisolo-Ssonko Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy University of Sheffield March 2014 Abstract This thesis aims to give an account of collective action. It starts with a detaile presentation of its underl!ing phenomenolog!. It is argue that in order to un erstan this phenomenolog!" we must move be!on the framework of individual agency$ thus re%ecting &ichael 'ratman's Share Cooperative Activit! Account. )oing so opens up a space for &argaret *ilbert's +lural Su#%ect Theor!. +lural Su#%ect Theor! is presente as capturing this phenomenolog! #! allowing that we can act as collective agents. ,owever" it also creates a pu--le centring on the relation #etween individual autonom! an constraint #! the collective will. The solution to this pu--le" this thesis argues" is to appl! 'ratman's planning theor! of agency to the collective agent. In doing so" *ilbert(s theor! is improve " such that it is #etter able to capture the sense in which living social lives entangles our sense of individual agentive identit! with our sense of collective agentive identit!. Acknowledgements I woul like to thank the .niversit! of Sheffiel Philosoph! Department for funding me to complete a research training &A and encouraging me to take up the Ph)$ the A,/C for providing me with the funding to allow me to undertake the Ph)$ and Steve )eegan for proofrea ing and recommending many a itional commas. I have #enefite greatl! from the guidance and support of m! supervisors" Paul 0aulkner and /osanna Keefe. -

O Gauge Products Through Traditional Or 21St-Century Media — Or Both

2015 Step Into Our Time Machine Just as smartphones reflect the most advanced technology of locomotives had on the American boy, and our time, tinplate trains brought the technological wonders of steamers reappeared in their product lines. the early 20th century right onto the living room floor. And by the middle of the decade, another new development was By the middle of the Roaring Twenties, the steam engine was introduced simultaneously by a century old but electric power was still new and magical. Lionel, Flyer, and the prototype Widespread electrification of households had gathered speed railroads: streamlining. only after World War I, and Americans had just begun to buy plug-connected appliances. In the world of railroading, as in In this, our seventh Lionel American society at large, many envisioned a world transformed Corporation catalog, we offer by electricity. The Pennsylvania Railroad was in the process of Lionel’s 1920s renditions of constructing the largest electrified corridor in the United States. the newest electric power Out west, the Milwaukee Road was conquering desolate moun- on American rails, along tain ranges with its Bi-Polar electric locomotives. with traditional steamers and several models from Lionel’s It was only natural then, that the Lionel® and American Flyer® first decade of production. And for the first time in more product lines in the 1920s would be dominated by models of than 80 years, we’re excited to announce new body styles in Traditional or electric locomotives. In fact, for half of the decade, not a single the 200 series freight cars, Lionel’s largest and most elaborate 21st-Century Electronics standard gauge steam engine was cataloged, and the first O Standard Gauge freighters. -

![A Survey of Statistical Network Models Arxiv:0912.5410V1 [Stat.ME]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7590/a-survey-of-statistical-network-models-arxiv-0912-5410v1-stat-me-617590.webp)

A Survey of Statistical Network Models Arxiv:0912.5410V1 [Stat.ME]

A Survey of Statistical Network Models Anna Goldenberg Alice X. Zheng University of Toronto Microsoft Research Stephen E. Fienberg Edoardo M. Airoldi Carnegie Mellon University Harvard University arXiv:0912.5410v1 [stat.ME] 29 Dec 2009 December 2009 2 Contents Preface 1 1 Introduction3 1.1 Overview of Modeling Approaches . .4 1.2 What This Survey Does Not Cover . .7 2 Motivation and Dataset Examples9 2.1 Motivations for Network Analysis . .9 2.2 Sample Datasets . 10 2.2.1 Sampson's \Monastery" Study . 11 2.2.2 The Enron Email Corpus . 12 2.2.3 The Protein Interaction Network in Budding Yeast . 14 2.2.4 The Add Health Adolescent Relationship and HIV Transmission Study 14 2.2.5 The Framingham \Obesity" Study . 16 2.2.6 The NIPS Paper Co-Authorship Dataset . 17 3 Static Network Models 21 3.1 Basic Notation and Terminology . 21 3.2 The Erd¨os-R´enyi-Gilbert Random Graph Model . 22 3.3 The Exchangeable Graph Model . 23 3.4 The p1 Model for Social Networks . 27 3.5 p2 Models for Social Networks and Their Bayesian Relatives . 29 3.6 Exponential Random Graph Models . 30 3.7 Random Graph Models with Fixed Degree Distribution . 32 3.8 Blockmodels, Stochastic Blockmodels and Community Discovery . 33 3.9 Latent Space Models . 36 3.9.1 Comparison with Stochastic Blockmodels . 38 4 Dynamic Models for Longitudinal Data 41 4.1 Random Graphs and the Preferential Attachment Model . 41 4.2 Small-World Models . 44 4.3 Duplication-Attachment Models . 46 4.4 Continuous Time Markov Chain Models . -

Dioramas in Palais De Tokyo 2017

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Oksana Chefranova Promenade through the theatre of illusion: Dioramas in Palais de Tokyo 2017 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3411 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Rezension / review Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Chefranova, Oksana: Promenade through the theatre of illusion: Dioramas in Palais de Tokyo. In: NECSUS. European Journal of Media Studies, Jg. 6 (2017), Nr. 2, S. 217–232. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3411. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://necsus-ejms.org/promenade-through-the-theatre-of-illusion-dioramas-in-palais-de-tokyo/ Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES www.necsus-ejms.org Promenade through the theatre of illusion: Dioramas in Palais de Tokyo NECSUS (6) 2, Autumn 2017: 217–232 URL: https://necsus-ejms.org/promenade-through-the-theatre-of- illusion-dioramas-in-palais-de-tokyo/ Keywords: art, dioramas, exhibition, Palais de Tokyo, Paris The exhibition Dioramas, curated by Claire Garnier, Laurent Le Bon, and Florence Ostende at Palais de Tokyo in Paris, proposes -

Download Full Document Here

Making Dioramas The Tawhiti Museum uses many models in its displays – from ‘life-size’ fi gures, the size of real people – right down to tiny fi gures about 20mm tall - with several other sizes in between these two. Why are different sizes used? To answer this, look at the Turuturu Mokai Pa model. The fi gures and buildings are very small. If we had used life-size fi gures and buildings the model would be enormous, bigger than the museum in fact –covering several hectares! So to make a model that can easily fi t into a room of the museum we choose a scale that we can reduce the actual size by and build the model to that scale – in the case of the Turuturu Mokai Pa model the scale is 1 to 90 (written as 1:90) – that means the model is one ninetieth of real size – or to put it another way, if you multiply anything on the model by 90, you will know how big the original is. A human fi gure on the model is 20mm – if you multiply that by 90 you get 1800mm - the height of a full size person. So as the modeler builds the model, by measuring anything from life (or otherwise knowing its size) and dividing by 90 he knows how big to model that item – this means the model is an accurate scale model of the original – there is no ‘guess work’. How do we choose which scale to make a model? There are three main considerations: 1) How much room do we have available for the display? Clearly the fi nished model needs to fi t into the available space in the museum, so by selecting an appropriate scale we can determine the actual size of the model. -

The Model As Three-Dimensional Post Factum Documentation

Beyond Simulacrum: The Model as Three-dimensional Post Factum Documentation Marian Macken Master of Architecture (Research) 2007 Certificate of Authorship / Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Marian Macken Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Andrew Benjamin and Dr Charles Rice, for their encouragement, support and close reading of my work; the staff at the School of Architecture, the Dean’s Unit and the Graduate School at the University of Technology, Sydney; and my friends and family, who gave more in their conversation than I suspect they realise. Table of Contents List of Illustrations ii Abstract vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Drawings and models as post factum documentation 7 Documentation The model as representation Drawings and models Historical overview The place of post factum documentation Chapter 2: The post factum model at a city scale 32 Case study: The Panorama model of New York City at the Queens Museum of Art. Chapter 3: The full-scale post factum model 55 Case study: The reconstruction of Mies van der Rohe’s German Pavilion, originally designed for the International Exposition, Barcelona 1928/29.