Thai-Burma Border Reproductive Health Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

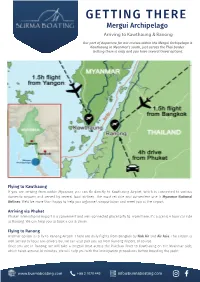

GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Arriving to Kawthaung & Ranong

GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Arriving to Kawthaung & Ranong Our port of departure for our cruises within the Mergui Archipelago is Kawthaung in Myanmar’s south, just across the Thai border. Getting there is easy and you have several travel options. Flying to Kawthaung If you are arriving from within Myanmar, you can fly directly to Kawthaung Airport, which is connected to various domestic airports and served by several local airlines. The most reliable and convenient one is Myanmar National Airlines. We’d be more than happy to help you organise transportation and meet you at the airport. Arriving via Phuket Phuket International Airport is a convenient and well-connected place to fly to. From there, it’s a scenic 4 hour car ride to Ranong. We can help you to book a car & driver. Flying to Ranong Another option is to fly to Ranong Airport. There are daily flights from Bangkok by Nok Air and Air Asia. The airport is well served by local taxi drivers but we can also pick you up from Ranong Airport, of course. Once you are in Ranong, we will take a longtail boat across the Pakchan River to Kawthaung on the Myanmar side, which takes around 30 minutes. We will help you with the immigration procedures before boarding the yacht. www.burmaboating.com +66 2 1070 445 [email protected] GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Crossing the Thai-Myanmar border In the case you arrive through the Thailand side and doesn’t want our assistance, here is a quick step by step instruction to cross the border between the 2 countries. -

ACU's Thai-Burma Program

ACU’s Thai-Burma Program: Engagement with the Myanmar refugee crisis Duncan Cooka and Michael Ondaatjeb a Academic Lead, Thai-Burma Program b Pro Vice-Chancellor (Arts and Academic Culture) National School of Arts, Australian Catholic University Paper presented at The ACU and DePaul University conference on community engagement and service learning. Tuesday 23 July, 2019 Introduction to ACU’s Thai-Burma Program Introduction video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dtvaXe2GYrQ 2 | Faculty of Education and Arts The East Myanmar-Thailand context • Myanmar (formerly Burma) • Approx. 6000 km northwest of Australia • Population: Approx. 54 million Thailand • At least 135 distinct ethnic groups • Land borders with Bangladesh, India, China, Laos and Thailand Myanmar 3 | Faculty of Education and Arts Historical/Political context of the refugee crisis • Thai-My border refugees since 1984 • Conflict dates back to at least 1949 • Longest running civil war in the world • Multiple East Myanmar ethnic groups fleeing armed conflict and persecution for three decades: Karen, Karenni, Mon and Shan, but others as well • ‘Slow genocide’ of ethnic minorities • Human rights violations by Burmese government • 2011: military-regime to a military-controlled government 4 | Faculty of Education and Arts The Thai-Myanmar Border context • Approx. 100,000 refugees in 9 camps in TL • Largest camp: Mae La, c. 36,000 people • Thailand: no national asylum systems, refugees often considered illegal migrants • No organised access to Thai education system • ACU’s operations -

Affect Forest and Wildlife?

HowHow WouldWould AffectAffect ForestForest andand Wildlife?Wildlife? 2 © W. Phumanee/ WWF-Thailand Introduction Mae Wong National Park is part of Thailand’s Western Forest Complex: the largest contiguous tract of forest in all of Thailand and Southeast Asia. Mae Wong National Park has been a conservation area for almost 30 years, and today the area is regarded internationally as a place that can offer a safe habitat and a home to many diverse species of wildlife. The success of Mae Wong National Park is the result of many years and a great deal of effort invested in conserving and protecting the Mae Wong forest, as well as ensuring its symbiosis with surrounding areas such as the Tung Yai Naresuan - Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, which was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1991. The large-scale conservation of these areas has enabled the local wildlife to have complete freedom within an extensive tract of forest, and to travel unimpeded in and around its natural habitat. However, even as Mae Wong National Park retains its status as a protected area, it stills faces persistent threats to its long-term sustainability. For many years, certain groups have attempted to forge ahead with large- scale construction projects within the National Park, such as the Mae Wong Dam. For the past 30 years, government officials have been pressured into authorizing the dam’s construction within the conservation area, despite the fact that the project has never passed an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). It is clear, then, that if the Mae Wong Dam project should go ahead, it will have a tremendously destructive impact on the park’s ecological diversity, and will bring about the collapse of the forest’s natural ecosystem. -

An Updated Checklist of Aquatic Plants of Myanmar and Thailand

Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1019 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1019 Taxonomic paper An updated checklist of aquatic plants of Myanmar and Thailand Yu Ito†, Anders S. Barfod‡ † University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand ‡ Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark Corresponding author: Yu Ito ([email protected]) Academic editor: Quentin Groom Received: 04 Nov 2013 | Accepted: 29 Dec 2013 | Published: 06 Jan 2014 Citation: Ito Y, Barfod A (2014) An updated checklist of aquatic plants of Myanmar and Thailand. Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1019. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1019 Abstract The flora of Tropical Asia is among the richest in the world, yet the actual diversity is estimated to be much higher than previously reported. Myanmar and Thailand are adjacent countries that together occupy more than the half the area of continental Tropical Asia. This geographic area is diverse ecologically, ranging from cool-temperate to tropical climates, and includes from coast, rainforests and high mountain elevations. An updated checklist of aquatic plants, which includes 78 species in 44 genera from 24 families, are presented based on floristic works. This number includes seven species, that have never been listed in the previous floras and checklists. The species (excluding non-indigenous taxa) were categorized by five geographic groups with the exception of to reflect the rich diversity of the countries' floras. Keywords Aquatic plants, flora, Myanmar, Thailand © Ito Y, Barfod A. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Bangkok Anesthesia Regional Training Center

RoleRole ofof BARTCBARTC (Bangkok(Bangkok AnesthesiaAnesthesia RegionalRegional TrainingTraining Center)Center) IInn cooperationcooperation inin educationeducation andand trainingtraining inin developingdeveloping countriescountries ProfProf TharaThara TritrakarnTritrakarn DirectorDirector ofof BARTCBARTC 14th WCA, Cape Town, South Africa, 3/1/2008 Oslo Center, Norway, 12/1/2008 ShortageShortage ofof anesthesiologistsanesthesiologists AA worldwideworldwide problemsproblems MoreMore seriousserious inin developingdeveloping poorpoor countriescountries MarkedMarked variationvariation amongamong countriescountries EconomyEconomy - Most important determining factors - Three levels of wealth & health - Rich countries (per capita GNP > $ 10,000) - Medium to low (GNP $ 1,000-10,000) - Poor countries (GNP < $ 1,000) RichRich && MediumMedium countriescountries GNPGNP PeoplePeople NumberNumber PeoplePeople perper capitacapita perper ofof perper (US(US $)$) doctordoctor anesthetistsanesthetists anesthetistanesthetist USA 33,799 387 23,300 11,500 Japan 34,715 522 4,229 20,000 Singapore 22,710 667 150 26,600 Hong Kong 23,597 772 150 40,000 Australia 19,313 2170 10,000 Malaysia 3,248 1,477 250 88,000 Thailand 1,949 2,461 500 124,000 Philippines 1,048 1,016 1176 64,600 MediumMedium && PoorPoor CountriesCountries GNPGNP PeoplePeople NumberNumber PeoplePeople perper capitacapita perper ofof perper (US(US $)$) doctordoctor anesthetistsanesthetists anesthetistanesthetist Indonesia 617 6,7866,786 350 591,000591,000 Pakistan 492 2,0002,000 400 340,000340,000 -

January 08-11 Pp01

ANDAMAN Edition Volume 18 Issue 2 January 8 - 14, 2011 Daily news at www.phuketgazette.net 25 Baht Booze ban hits park tourists Teen stabbing sparks alcohol ban in national parks By Atchaa Khamlo derstand and have given us very Standard procedure is for staff good co-operation. The situation to ask people trying to bring alco- THE directors of several national is under control,” he said. hol into the park to leave it with parks in the Andaman region say Most of those warned about officers during their visit, he said. they have received good compli- drinking in the park were Thais, “We prefer to ask people for ance with the ban on alcohol in- but a few were foreigners. their co-operation rather than side parks that came into effect “As the park is quite expansive, threaten them with punishment. It on December 27. sometimes people might be drink- seems our public relations cam- Natural Resources and Envi- ing inside without our being aware paign is going well, as most people ronment Minister Suwit Khunkitti of it,” he added. just drink Coke or water,” he said. issued the ban immediately follow- Two signs declaring the park “Most foreigners understand ing the December 26 stabbing an alcohol prohibition zone are quite well. Not many of them drink murder of a student by a group of now being constructed and should whiskey, but some like to drink drunken schoolmates camping at go up at both entrances very soon, beer. But they don’t seem to have Khao Yai National Park in Surat along with a third sign to go up in any problem with alcohol being Thani. -

Learning in Action: an Investigation Into Karen Resettlement

LEARNING IN ACTION: AN INVESTIGATION INTO KAREN RESETTLEMENT VIA PARTICIPANT OBSERVATION AND PARTICIPATORY ACTION RESEARCH by DANIEL JOSEPH GILHOOLY (Under the Direction of Ruth Harman) ABSTRACT This qualitative research study is informed by my three and a half years participant observation within one Karen community living in rural eastern Georgia and the result of a participatory action research (PAR) project performed alongside three adolescent Karen brothers from 2010 to 2012. Such a fusion of methodologies is what Nelson and Wright (1995) describe as ‘creative synthesis’ where research is done both with and on participants. The first findings chapter (Chapter Six) analyzes how three adolescent Sgaw Karen brothers use online digital literacies to cope with resettlement. This component of the study explores the digital literacy practices of three adolescent Karen brothers as they attempt to navigate multiple institutions like school. Findings from this study suggest that newly arrived immigrant youth benefit in many social, psychological, and academic ways as a result of their online presence. The study looks specifically at how they use online spaces to (a) maintain and build co-ethnic friendships, (b) connect to the wider Karen Diaspora community, (c) sustain and promote ethnic solidarity and, (d) create and disseminate digital productions. This component of the study offers insights that can help teachers better understand their students’ out-of-school literacy practices and ways they can incorporate such digital literacies in more formal educational contexts. This study also provides findings about Karen resettlement via the collaborative enactment of a participatory action research (PAR) project between these three Karen brothers and myself. -

Livelihoods, Integration & Transnationalism in a Protracted

| I LIVELIHOODS, INTEGRATION & TRANSNATIONALISM IN A PROTRACTED REFUGEE SITUATION CASE STUDY: BURMESE REFUGEES IN THAILAND Dissertation presented in fulfilment of the requirements for a Ph.D. degree in Political and Social Sciences, option Political Sciences. INGE BREES Ghent University August 2009 Thesis director: Prof. Dr. Koen Vlassenroot | II | III LIVELIHOODS, INTEGRATION & TRANSNATIONALISM IN A PROTRACTED REFUGEE SITUATION CASE STUDY: BURMESE REFUGEES IN THAILAND Dissertation presented in fulfilment of the requirements for a Ph.D. degree in Political and Social Sciences, option Political Sciences. INGE BREES Ghent University August 2009 Thesis director: Prof. Dr. Koen Vlassenroot | I CONTENT LIST OF TABLES, MAPS AND FIGURES .......................................................................... IV ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................. V ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. IX INTRODUCTION: HOW THIS RESEARCH FITS INTO THE DEBATES IN REFUGEE STUDIES AND POLICY ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Two settlement options: Refugee camps or self-settlement ............................... 3 1.2 The livelihoods approach ................................................................................... 7 1.3 Transnationalism and its impact ....................................................................... -

Military Brotherhood Between Thailand and Myanmar: from Ruling to Governing the Borderlands

1 Military Brotherhood between Thailand and Myanmar: From Ruling to Governing the Borderlands Naruemon Thabchumphon, Carl Middleton, Zaw Aung, Surada Chundasutathanakul, and Fransiskus Adrian Tarmedi1, 2 Paper presented at the 4th Conference of the Asian Borderlands Research Network conference “Activated Borders: Re-openings, Ruptures and Relationships”, 8-10 December 2014 Southeast Asia Research Centre, City University of Hong Kong 1. Introduction Signaling a new phase of cooperation between Thailand and Myanmar, on 9 October 2014, Thailand’s new Prime Minister, General Prayuth Chan-o-cha took a two-day trip to Myanmar where he met with high-ranked officials in the capital Nay Pi Taw, including President Thein Sein. That this was Prime Minister Prayuth’s first overseas visit since becoming Prime Minister underscored the significance of Thailand’s relationship with Myanmar. During their meeting, Prime Minister Prayuth and President Thein Sein agreed to better regulate border areas and deepen their cooperation on border related issues, including on illicit drugs, formal and illegal migrant labor, including how to more efficiently regulate labor and make Myanmar migrant registration processes more efficient in Thailand, human trafficking, and plans to develop economic zones along border areas – for example, in Mae 3 Sot district of Tak province - to boost trade, investment and create jobs in the areas . With a stated goal of facilitating border trade, 3 pairs of adjacent provinces were named as “sister provinces” under Memorandums of Understanding between Myanmar and Thailand signed by the respective Provincial governors during the trip.4 Sharing more than 2000 kilometer of border, both leaders reportedly understood these issues as “partnership matters for security and development” (Bangkok Post, 2014). -

Migration, Trafficking & Exploitation of Women In

NO STATUS: MIGRATION, TRAFFICKING & EXPLOITATION OF WOMEN IN THAILAND Health and HIV/AIDS Risks for Burmese and Hill Tribe Women and Girls A Report by Physicians for Human Rights © Physicians for Human Rights, Boston, MA June 2004 Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved Report Design: Visual Communications/www.vizcom.org Cover Photo: Paula Bronstein/Liaison CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................................................................v Glossary ....................................................................................vii I. Executive Summary ...........................................................1 II. Introduction.......................................................................7 III. Thailand Background......................................................11 IV. Burma Background..........................................................19 V. Project Methodology .......................................................25 VI. Findings...........................................................................27 Hill Tribe Women and Girls in Thailand..........................28 Burmese Migrant Women and Girls in Thailand..............33 VII. Law and Policy – Thailand..............................................45 VIII. Applicable International Human Rights Law ..................51 IX. Law and Policy – United States .......................................55 X. Conclusion and Expanded Recommendations .................59 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was written by Karen Leiter, JD, -

Transport Logistics

MYANMAR TRADE FACILITATION THROUGH LOGISTCS CONNECTIVITY HLA HLA YEE BITEC , BANGKOK 4.9.15 [email protected] Total land area 677,000sq km Total length (South to North) 2,100km (East to West) 925km Total land boundaries 5,867km China 2,185km Lao 235km Thailand 1,800km Bangladesh 193km India 1,463km Total length of coastline 2,228km Capital : Naypyitaw Language :Myanmar MYANMAR IN 2015 REFORM & FAST ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS SIGNIFICANT POTENTIAL CREDIBILITY AMONG ASEAN NATIONS GATE WAY “ CHINA & INDIA & ASEAN” MAXIMIZING MULTIMODALTRANSPORT LINKAGES EXPEND GMS ECONOMIC TRANSPORT CORRIDORS EFFECTIVE EXTENSION INTO MYANMAR INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTION TRADE AND LOTISGICS SUPPLY CHAIN TRANSPARENCY & PREDICTABILITY LEGAL & REGULATORY FREAMEWORK INFRASTUCTURE INFORMATION CORRUPTION FIANACIAL SERVICE “STRENGTHEING SME LOGISTICS” INDUSTRIAL ZONE DEVELOPMENT 7 NEW IZ KYAUk PHYU Yadanarbon(MDY) SEZ Tart Kon (NPD) Nan oon Pa han 18 Myawadi Three pagoda Existing IZ Pon nar island Yangon(4) Mandalay Meikthilar Myingyan Yenangyaing THI LA WAR Pakokku SEZ Monywa Pyay Pathein DAWEI Myangmya SEZ Hinthada Mawlamyaing Myeik Taunggyi Kalay INDUSTRIES CATEGORIES Competitive Industries Potential Industries Basic Industries Food and Beverages Automobile Parts Agricultural Machinery Garment & Textile Industrial Materials Agricultural Fertilizer Household Woodwork Minerals & Crude Oil Machinery & spare parts Gems & Jewelry Pharmaceutical Electrical & Electronics Construction Materials Paper & Publishing Renewable Energy Household products TRANSPORT -

Charlie Thame and Kraiyos Patrawart February 2017

Charlie Thame and Kraiyos Patrawart February 2017 Strengthening Out of School Children (OOSC) Mechanisms in Tak Province (February 2017) Charlie Thame and Kraiyos Patrawart ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Cover photo by Kantamat Palawat Published by This report was written by Charlie Thame and Kraiyos Patrawart. Both would like to thank Save the Children Thailand all those who contributed to the project, which would not have been possible without the kind 14th Fl., Maneeya Center Building (South), 518/5 Ploenchit Road, support of several individuals and organisations. Special thanks are extended to the Primary Lumpini, Pathumwan, Bangkok 10330, Thailand Education Service Area Office Tak 2 (PESAO Tak 2), Tak Province. Khun Pongsakorn, Khun +66(0) 2684 1286 Aof, and Khun Ninarall graciously gave their time and support to the team, without which the [email protected] study would not have been possible. Aarju Hamal and Sia Kukuawkasem provided invaluable http://thailand.savethechildren.net research assistance with documentary review, management and coordination, and translation. Siraporn Kaewsombat’s assistance was also crucial for the success of the project. The team would like to express further thanks to all at Save the Children Thailand for their support during the study, particularly Tim Murray and Kate McDermott. REACT The Reaching Education for All Children in Thailand (REACT) project is supported by Save the Children Hong Kong and implemented by Save the Children International in Thailand. REACT aims to ensure migrant children in Thailand have access to quality basic education and communities support children’s learning. The main target groups are the migrant children in Tak and Ranong provinces.