State of the W Orld 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing & Reading Classes

ALL CLASSES ONLINE Winter 2021 writing & reading classes oo TABLE OF CONTENTS COVID-19: All Winter 2021 classes will take place online. About Our Classes ... 2 All classes are listed in Pacific Time. Highlights ... 3 Classes listed as “Asynchronous” will be held on our Wet Ink platform that allows for asynchronous learning. Students will receive Fiction ... 4 an invitation to join Wet Ink on the class start date. Nonfiction ... 9 Poetry ... 14 Mixed Genre ... 19 Writing for Performance ... 25 Reading ... 26 The Writing Life ... 27 Free Resources ... 28 About Our Teachers ... 30 iiii From Our Education Director REGISTRATION Register by phone at 206.322.7030 There is so much to celebrate as we head into a new year. The lengthening or online at hugohouse.org. days. The literal and figurative turning of pages. The opportunity to renew, recommit, and revise. All registration opens at 10:30 am $500+ donor registration: November 30 This quarter, Vievee Francis and Emily Rapp Black will offer perfect new- Member registration: December 1 year classes: “The Ars Poetica and the Development of a Personal Vision” General registration: December 8 and “Crafting an Artistic Intention,” respectively. Bonnie J. Rough’s “Diving In: First Pages,” Susan Meyers’s “Write Your Novel Now,” and Register early to save with early bird Elisabeth Eaves’s “Launch Your Longform Journalism Project” will offer pricing, in effect November 30– structure and support for your new beginnings, as will any of our tiered December 14. classes in poetry, creative nonfiction, or fiction. If you already have a manuscript in the works, take a close look at your SCHOLARSHIPS storytelling structure with Lauren Groff, the architecture of your story with Sunil Yapa, scenes with Becky Mandelbaum, dialogue with Evan Need-based scholarships are available Ramzipoor, backstory with Natashia Deón, and characters with Liza every quarter. -

Cuaderno De Documentacion

SECRETARIA DE ESTADO DE ECONOMÍA, MINISTERIO SECRETARÍA GENERAL DE POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA DE ECONOMÍA Y ECONOMÍA INTERNACIONAL Y HACIENDA SUBDIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE ECONOMÍA INTERNACIONAL CUADERNO DE DOCUMENTACION Número 94 ANEXO V Alvaro Espina Vocal Asesor 12 Julio de 2011 ENTRE EL 1 Y EL 15 DE MAYO DE 2011(En sentido inverso) 1 0 MOISÉS NAÍM ¿Por qué Libia sí y Siria no? Los sirios desafían a los tanques sin más armas que sus deseos de cambio MOISÉS NAÍM 15/05/2011 ¿Cómo explicar que Estados Unidos y Europa estén bombardeando a Trípoli con misiles y a Damasco con palabras? ¿Por qué tanto empeño en sacar al brutal tirano libio del poder y tanto cuidado con su igualmente salvaje colega sirio? Comencemos por la respuesta más común (y errada): es por el petróleo. Libia tiene mucho y Siria, no. Y por tanto, según esta explicación, el verdadero objetivo de la agresión militar contra Libia son sus campos petroleros. Siria se salva por no tener mucho petróleo. El problema con esta respuesta es que, en términos de acceso garantizado al petróleo libio, Gadafi era una apuesta mucho más segura para Occidente que la situación de caos e incertidumbre que ha producido esta guerra. Las empresas petroleras de Occidente operaban muy bien con Gadafi. No necesitaban cambiar nada. Una segunda, y común, manera de contestar la pregunta es denunciando la hipocresía estadounidense: Washington nos tiene acostumbrados al doble rasero y a las contradicciones en sus relaciones internacionales. Esta tampoco es una respuesta muy útil, ya que no nos ayuda a entender las causas de estas contradicciones. -

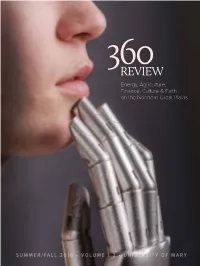

360-Review-1.2-Final.Pdf

Energy, Agriculture, Finance, Culture & Faith on the Northern Great Plains SUMMER/FALL 2016 • VOLUME 1.2 • UNIVERSITY OF MARY 360 REVIEW magazine covers energy, agriculture, finance, culture and faith on the Northern Great Plains. 360 Review presents in-depth inquiry, analysis and reflection on important issues, trends and events happening in and affecting this region. There is a special focus on North Dakota, where we are located. More stories about surrounding states will published in future issues. “Magazine” derives from makhazin, the Arabic word for “storehouse,” which also soon gained military application as a “store for arms.” The world’s first print magazines began publication in England in the 18th century and sought to provide a storehouse of information and intellectual armament. 360 Review joins that tradition with the Christian, Catholic and Benedictine tradition of the University of Mary, which exists to serve the religious, academic and cultural needs of people in this region and beyond. As a poet once wrote: “The universe is composed of stories, not atoms.” 360 Review strives to tell some of these stories well—on paper (made of atoms, we presume), which is retro-innovative in a world spinning into cyberspace. There is also a digital version, available at: www.umary.edu/360. Publisher: University of Mary Editor-in-Chief: Patrick J. McCloskey Art Director & Photographer: Jerry Anderson Director of Print & Media Marketing: Tom Ackerman Illustrator: Tom Marple Research & Graphics Assistant: Matthew Charley Editorial Offices: University of Mary, 7500 University Drive, Bismarck, ND 58504 Signed articles express the views of their authors and are intended solely to inform and broaden public debate. -

APR 2016 Part B.Pdf

Page | 1 CBRNE-TERRORISM NEWSLETTER – February 2016 www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com Page | 2 CBRNE-TERRORISM NEWSLETTER – February 2016 ISIS Wants a Dirty Bomb, a Weapon of Mass Disruption Source:https://www.inverse.com/article/13180-isis-wants-a-dirty-bomb-a-weapon-of-mass-disruption Mar 22 – ISIS, which has claimed responsibility not, in fact, charged with his dirty for the attack in Brussels today, and associated bomb designs, because he was radicals have been increasingly active in unable to progress beyond Belgium during the months leading up to this planning to whirl buckets of latest act of terror. In November, a man living uranium over his head to near Brussels and linked to the Islamic State separate the U-235 isotope for group was arrested; according to an his nuclear device. investigation by the nonprofit Center of Public The fissile materials at the Integrity, officials found evidence he was center of a nuke — like enriched surveilling a Belgian nuclear facility with uranium — are both prohibitively the goal of creating a dirty bomb. difficult to create and obtain. If you are unfamiliar with the family tree of Daily life, that said, is far from explosives, a dirty bomb is meant to radioisotope-free. There are thousands of disseminate chaos and mayhem. However, it known radioactive materials, wrote Center for will not result in the high body counts popularly Technology and National Security Policy associated with radioactive weaponry. What researchers Peter D. Zimmerman and Cheryl makes a dirty bomb “dirty” is the dispersal of Loeb in a 2004 report. But “only a few stand radioactive material.