THE INNER GAME of SITUATION COMEDY Notes from the AFTRS Sitcom Forum by John Vorhaus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sketch Idea Generator

Sketch Idea Generator This is a guide you can use to generate sketch ideas. Keep in mind that out of 10 ideas in comedy, maybe 1 is going to turn out great. But, using these methods you can pump out ideas very quickly and get to that 1 really great idea faster. Enjoy! Adjective/ Profession/ Location Mis/Matching This one is all about pumping out ideas quickly. Make 3 lists. First a list of adjectives. Second a list of professions. Third a list of locations. Then you just connect them in a way that makes sense or in a way that makes no sense at all. Here’s an example: Adjectives Professions Locations Loud A Barista Office Quiet B Librarian A Art Museum A Brave Actor B Truck Stop C Scared C Trash Collector Library Childish Singer Restaurant Smart Mechanic C Home Responsible Pope Grocery Store B If this were on sheet paper by hand I would just draw arrows (i suggest doing it that way). But, for the sake of keeping this digitally coherent, here are some connections I could make: A) Loud > Librarian > Art Museum B) Quiet > Actor > Grocery Store C) Scared > Mechanic > Truck Stop And so on… Then you look at your connections and you try to think of some situation that those make sense. Or you go the complete opposite and connect ones that are total rubbish to put together. For example, what if a librarian, who is forced to stay quiet in her natural environment (the library) made up for it by being loud everywhere else? Next, you would brainstorm that scenario. -

What Happened ALONG the WAY

Annual Report 20What happened19 ALONG THE WAY... MISSION To empower people of all ages through an array of human services and advocacy MERIT Established in 1850, Waypoint is a private, nonprofit organization, and the oldest human service/children’s charitable organization in New Hampshire. A funded member of the United Way, Waypoint is accredited by the Council on Accreditation, is the NH delegate to the Children’s Home Society of America, and is a founding member of the Child Welfare League of America. WAYPOINT Statewide Headquarters P.O. Box 448, 464 Chestnut Street, Manchester, NH 03105 603-518-4000 800-640-6486 www.waypointnh.org [email protected] Welcome to Waypoint. This is our 2019 Annual Report. It was a good year. We’ll give you the highlights here. That way, you can get the picture of how we did in 2019, with your help, and then get right back to what you were doing... adjusting to life in unprecedented times while continuing to be an amazing human being who is making an impact. Here’s what you’ll find in this publication: uMission & merit statements uMessage from our leaders uPeople served by program uOutcomes measures of our work uFinancial overview uLegislative recap uDonor honor roll listing uBoard listing uHeadquarters information 1 Message from our Dear Friends, Leaders You know, we feel rather sorry for 2019. It got sandwiched between our milestone year of 2018 when we rebranded and changed our name to Waypoint, and 2020 when our world turned upside down. Now with a global pandemic, political divides, soaring unemployment, extreme natural disasters, civil unrest and an international uprising against racial injustice, the months before this seem to pale in comparison. -

Ronnie Ray "Very Talented Comedian"

Ronnie Ray "Very Talented Comedian" Ronnie Ray has tremendous presence no matter what he does – Beth Lisick, The San Francisco Chronicle Originally from the south side of Chicago, Ronnie Ray’s passion in comedy transcribes into hilarious real life moments brought to the stage! Trained at The Second City Chicago Ron performs with sketch comedy ensemble Oui Be Negroes and Nation of Improv. As a stand-up comedian his material spans from a PG-13 to an R rating, with subjects that consist of growing up on the South Side of Chicago, the different types of comedians and the often requested crowd favorite that basketball star Shaquille O’Neal should retire from NBA and go back to his career as a rap artist. He his performed at a variety of clubs such as The World Famous Comedy Store (Hollywood), The Laugh Factory (Hollywood), The Improv (West Palm Beach) and Pechanga Comedy Club (Temecula) just to name a few and have been privileged to share the stage with comedy greats such as Damon Waynes, Chris Tucker and Robin Williams. His uniqueness as a comedic actor has given him the opportunity and distinction of being the only comic to perform on Playboy TV (Canoga Park and Totally Busted) AND Nickelodeon (Victorious) along with other T.V. and Movies projects. Such as Paramount Pictures “Save the Last Dance”, Groit Pictures “Redrum”, adding his voice to the Animation “Gangs of LA 1991_ and the award winning comedy from Jib Jab’s Shawshank in Minute, directed by John Landis. A gifted comedic writer, He has written numerous sketch comedy scenes of OBN and has written many spec productions with QRS Productions. -

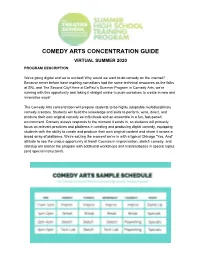

Comedy Arts Concentration Guide Virtual Summer 2020 Program Description

COMEDY ARTS CONCENTRATION GUIDE VIRTUAL SUMMER 2020 PROGRAM DESCRIPTION We’re going digital and we’re excited! Why would we want to do comedy on the internet? Because never before have aspiring comedians had the same technical resources as the folks at SNL and The Second City! Here at DePaul’s Summer Program in Comedy Arts, we’re running with this opportunity and taking it straight online to push ourselves to create in new and innovative ways! The Comedy Arts concentration will prepare students to be highly adaptable multidisciplinary comedy creators. Students will build the knowledge and skills to perform, write, direct, and produce their own original comedy as individuals and an ensemble in a fun, fast-paced environment. Comedy always responds to the moment it exists in, so students will primarily focus on relevant practices and platforms in creating and producing digital comedy, equipping students with the ability to create and produce their own original content and share it across a broad array of platforms. We’re seizing the moment we’re in with a typical Chicago “Yes, And” attitude to see the unique opportunity at hand! Courses in improvisation, sketch comedy, and standup will anchor the program with additional workshops and masterclasses in special topics (and special instructors!). SAMPLE SCHEDULE (CENTRAL DAYLIGHT TIME) Includes daily writing/digital content assignments, viewing & reading assignments. MONDAY 11:00-1:00pm Improv 1:00-2:00pm Lunch w/ optional Zoom hangouts 2:00-4:00pm Sketch Comedy 4:00-5:00pm Tech Lab TUESDAY -

Immediacy in Comedy: How Gertrude Stein, Long Form Improv, and 5 Second Films Can Revolutionize the Comedic Form

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2013 Immediacy In Comedy: How Gertrude Stein, Long Form Improv, And 5 Second Films Can Revolutionize The Comedic Form Alexander Hluch University of Central Florida Part of the Acting Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Hluch, Alexander, "Immediacy In Comedy: How Gertrude Stein, Long Form Improv, And 5 Second Films Can Revolutionize The Comedic Form" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2933. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2933 IMMEDIACY IN COMEDY: HOW GERTRUDE STEIN, LONG FORM IMPROV, AND 5 SECOND FILMS CAN REVOLUTIONIZE THE COMEDIC FORM by ALEX HLUCH M.A. in Theatre, Bowling Green State University, 2010 B.A. in Theatre, Ohio State University, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Acting in the department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2013 ABSTRACT Comedy has typically been derided as second-tier to drama in all aspects of narrative. Throughout history, comedy has seen short shrift in both critical reception and academic investigation. Merit is simply placed on drama far before that of comedy. -

Article Cognitive Distortions and Hilarious Implementations of the Principles of Relevance Theory Iché V3

Cognitive Distortions and Hilarious Implementations of the Principles of Relevance Theory: The Case of Coach in Cheers (NBC, 1982-1985) Virginie Iché, MCF, Université Paul Valéry Montpellier 3, EMMA EA 741 Cognitive distortions can result from two major sources: faulty processing of the physical world (mainly due to perceptual disabilities), or erroneous treatment of the information processed (due to flawed or poor inferential disabilities or to psychopathological disorders impacting the interlocutor’s inferential abilities). Cognitive impairments in otherwise healthy individuals—such as sudden vision loss, comprehension difficulties, language impairment, attention or memory disorders, to name but a few—are cause for worry and medical scrutiny, since they are usually the sign of brain decline, depression or even dementia. Additionally, these distortions impact the way speakers interpret their cognitive environment 1 and result in unconventional behavioral or discursive reactions. Coach, one of the main characters of the first three seasons of the American sitcom Cheers (1982-1985), displays many cognitive misfires over the episodes—all of which take place (almost exclusively) in a bar in Boston, run by a former baseball player named Sam Malone and tended by Ernie Pantusso, nicknamed “Coach” because he used to be a coach. Coach’s cognitive abilities are repeatedly shown to be flawed—he is unable to understand non-literal utterances, has recurrent memory lapses (even concerning his own name) and has a hard time analyzing his environment. The canned laughter that follows Coach’s cues suggests the cognitive impairments he suffers from and the discursive consequences these distortions have on the situation and the dialogue, are nothing to worry about though—they even prove to be one of the sitcom’s comic features. -

Sketch Comedy 2019 Syllabus

THTR 470: Sketch Comedy for Theatre 2 Units Fall 2019—Mon/Wed—12-1:50pm Location: MCC 107 Instructor: Kirstin Eggers Office: MCC 214 Office Hours: By appointment — please schedule via email. Email: [email protected] Phone: (c) 323.898.7388 — emergencies only, email preferred. Course Description “The duty of comedy is to correct men by amusing them.” — Molière In this experiential writing and performance workshop course, students will explore and develop their unique comedic voices via the creation of comedic sketches, through the entire process — from idea generation, to writing, revision, rehearsal, and finally production and performance of a fully realized sketch comedy show, with an emphasis on creative collaboration and ensemble building. Learning Objectives Throughout this course, students will work to identify their own comedic viewpoints through the medium of sketch — comedic explorations of concepts, characters and situations. Students will learn sketch writing structure through the study of prominent existing sketches, and techniques for sketch performance and original character creation. Students are expected to generate a high volume of comedic concepts and written material to serve their own creative exploration, and their own work ethic and writing practice. Students are also expected to serve the needs of the group, and work toward building a true comedy ensemble. Although we will be working toward a final workshop presentation, this course is focused on process over product — you are not expected to be funny 100% of the time, or even 10% of the time. You are expected to be brave, be open- minded, and stretch out of your comfort zone to explore and strengthen your own unique comedic voice. -

Film 150: Screenwriting

PROVISIONAL SYLLABUS: Subject to Change – Film 150: Screenwriting Film 150 Screenwriting (M & F 1 - 5 pm) Natasha V. Summer Session 1: June 26 - July 28 [email protected] Class Location: Rm 141, Soc Sci 2 Office Hours: M/F noon - 1 b4 class Office Location: TBA And by appt (email request) This is an introductory course in which students learn some basic principles of screenwriting, in the context of a Sketch Comedy Workshop class. Emphasis this Summer is on Sketch Comedy Writing, and how Sketch differs from other types of comedy (Stand Up, Sitcoms, Comedic Feature Films, & Improv vs. Written Skits.) Telling jokes is how we critique and understand the world, ourselves, and other people. Having a funny idea, and wanting to share it, is a deeply human impulse. Your job, as screenwriters, is to learn to write your sketches in the funniest, most effective way possible for an audience. You want to move people to laughter so they can understand something new and unique about life. The main activity of this class is writing——you’ll write at least TEN short comedy sketches, ½ - 4 pages in length each. (“Brevity is the soul of wit” – W. Shakespeare.) We will be primarily concerned with STRUCTURE, CHARACTER, and HUMOR, as key components in sketch writing. We will analyze television sketch shows and your own scripts in terms of their structure, characters, and comedic effectiveness. Becoming a better writer is a journey, and we all learn by attempting things and growing beyond our limitations. We learn by WRITING, first and foremost. I will expect you to write MORE sketches than those you decide to present in class, and I expect you to revise your writing both before and after you present in class. -

Samuel Epstein 1 9 1 9 — 2 0 0 1

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES SAMUEL EPSTEIN 1 9 1 9 — 2 0 0 1 A Biographical Memoir by HUGH P. TAYLOR JR. AND ROBERT N. CLAYTON Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 2008 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON, D.C. SAMUEL EPSTEIN December 9, 1919–September 17, 2001 BY HUGH P. TAYLOR JR . AND ROBERT N. CLAYTON AMUEL EPSTEIN WAS ONE of the principal geochemists re- Ssponsible for pioneering discoveries regarding variations of the stable isotopes of oxygen, hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, silicon, and calcium on Earth, the Moon, and in meteorites. He was fortunate to have been at the forefront of great advances in the physics and chemistry of isotopes that were an outgrowth of atomic energy investigations in the wake of World War II. Although several scientists in the 1950s and 1960s recognized the power of stable isotope measurements to solve scientific problems, it was Sam more than anyone else who had the energy and insight to carry this out in such fundamental ways and in so many diverse fields, including: paleothermometry of carbonate fossils; geothermometry of minerals and rocks; origins of natural waters, including fluid inclusions in minerals; paleoclimatology records in glaciers, continental ice sheets, and tree rings; biological processes including living plants and animals, fossil plants and animals, and paleodiets; petroleum and natural gas; hydrothermal ore deposits; water and rock interactions; oceanography; meteorology; gases in Earth’s atmosphere; weathering and soil formation; studies of meteorites, lunar rocks, and tektites; and studies of igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks and their constituent minerals. -

Deconstructing "Chappelle's Show": Race, Masculinity,And Comedy As Resistance Lyndsey Lynn Wetterberg Minnesota State University - Mankato

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects 2012 Deconstructing "Chappelle's Show": Race, Masculinity,and Comedy As Resistance Lyndsey Lynn Wetterberg Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the African American Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wetterberg, Lyndsey Lynn, "Deconstructing "Chappelle's Show": Race, Masculinity,and Comedy As Resistance" (2012). Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 133. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. i DECONSTRUCTING “CHAPPELLE’S SHOW”: RACE, MASCULINITY, AND COMEDY AS RESISTANCE by LYNDSEY L.WETTERBERG A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS IN GENDER AND WOMEN’S STUDIES MINNESOTA STATE UNIVERSITY MANKATO, MINNESOTA JULY 2012 ii Deconstructing Chappelle’s Show: Race, Masculinity, and Comedy as Resistance Lyndsey Wetterberg This thesis (or dissertation) has been examined and approved by the following members of the thesis (or dissertation) committee. Dr. Helen Crump, Advisor Committee Member, Dr. Shannon Miller Committee Member, Dr. Kristen Treinen iii Abstract “Chappelle’s Show” is a sketch comedy series that ran from 2003-2004 and that was created by and starred comedian Dave Chappelle. -

Intertextuality and Understanding Dave Chappelle's Comedy

Intertextuality and Understanding Dave Chappelle’s Comedy DAVID GALVEZ Produced in Dan Martin’s Fall 10 ENC1101 In an American culture where individual achievements and a maverick approach are praised, people tend to forget that “nothing is new under the sun” and that their ideas and thought processes are molded by their everyday experiences in their particular environment. The reality (and beauty) of authorship is that, in the words of James Porter, “the creative mind is the creative borrower” (110). Intertextuality, however, becomes controversial when it comes to defining sole authorship. Any text can be praised as creative (assuming it hasn’t been copied from any source word for word), but not because it’s something never before seen. Rather, sole authorship is the innovative arrangement of pre-existing ideas recognized by an audience who understands and interprets the work of the author as “original,” based on their own representations. In other words, it’s up to the individual to determine whether the text is original or plagiarized. If it looks like a duck and sounds like a duck, it isn’t necessarily a duck. Since each individual interprets a text differently from everyone else, there can really be no universally accepted way of differentiating sole authorship from plagiarism. In this paper I’ll discuss how an author uses “creativity through borrowing” through a sketch comedy clip from Chappelle’s Show and how an audience uses intertextuality to get something out of the text. In doing this, I’ll explain why every work, unless blatantly copied word for word, has a sole author. -

•Now Pitcbincj: Sam Malone• Written by Ken Levine, David Isaacs

, CBDRS •Now PitcbincJ: Sam Malone• 160591-016 Written By Ken Levine, David Isaacs Created and Developed By James Burrows Glen Charles Les Charles Return to Script Department PARAMOUNT PIC'l'traES CORPORATION PINAL DRAFT 5555 Melrose Avenue Hollywood, California 90038 December 9, 1982 CBEBRS •Now Pitcbin91 ~ SAM MALONE ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• DD DANSON DIANE CBAMBERS ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• SBBLLBY LONG COACH ERNll PANTUSSO ••••• •••••••••••••••••• NICX COLASANTO CARLA TORffLLI • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • RHEA PERLMAN CI.IPF • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. • JORN' RA'tZENBERGER NORM. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • GEORGB 1IENDT LANA MARSHALL •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• BARBARA BABCOCK TIBOR SVE'l'KOVIC. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • RICX BILL PAUL.. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •.• • • PAOL VAUGHN LUIS TIANT ••••••••• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • BIMSBLF DIRECTOR ••••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••• • ••• nrr. BAR INT. SAM'S OFFICE CHBBRS •Nov Pitching: Sam Malone• .. TEASER -X FADE IN: INT. BAR - CLOSING TIME SAM AND COACH ARE CLOSING tJP. AS THEY HEAD FOR THE DOOR, COACH STOPS AND LOOKS AROUND. COACH Y'know Sam, this is my favorite time of day. SAM Closing time, Coach? COACH No, 1:37. SOmething about it, I don't know ••• SAM Yeah, it's nice. Everybody's probably got their favorite 1:37 story. 2. (X) 1eah. What time of day do you like, S&m? SAM Gee, I don't Jcnow ••• 8115'• nice. COACH I used to like 8:15, but I kinda outgrew it. AS THBY 'l'ALK, SAM 'l'tJRNS 00'1' THE LIGHTS. 'l'BBY GO 00'1' 'l'HB DOOR, UP '1'BB S'l'EPS AND DISAPPEAR. AP'l'ER A BEA'l' NORM COMES ROSSING QY! OP 'l'HB BATHROOM. NORM Wait a minute, I ••• BB STOPS, A THOOGH'l' OCCURS TO HIM. HE LOOKS AROUND,; GOES OVER AND TtJRNS ON 'l'HE TV.